ALTA Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

ALTA Law Research Series |

|

Subject libraries in free access law services[*]

Graham Greenleaf [**]

1 July 2008

Abstract

Free-access Legal Information Institutes (LIIs) like AustLII have an increasing wealth and diversity of legal data, including legislation from numerous jurisdictions, decisions of both general and specialised tribunals, and sometimes law reform reports, law journals, treaties etc. This profusion of content leads to problems in precision of searches. One way commercial publishers have dealt with this, and added value to their content, is by creating subject-specific research facilities on topics such as environmental law, IP, criminal procedure etc. The challenge for free-access LIIs is that any such value-adding cannot involve the high costs of constant editorial intervention, nor the commissioning of subject-specific commentaries. This paper explains experiments by AustLII to create useful subject-specific 'Libraries' in areas of Australian law such as indigenous law, taxation and industrial law, and on international and humanitarian law (on WorldLII). The experiments involve methods of identifying and isolating within databases of general content that which is on specified subjects, by largely automated and repeatable means, particularly the use of approximating searches. Methods of testing the searches used to construct Libraries are suggested. Once a subject-specific Library is created, it can be used as a context to provide access to equally specific content provided by search engines or commercial publishers. Systems like WorldLII which draw together the content of many LIIs pose similar challenges at the international level, but may make possible international comparative law facilities.

Prefatory note: Dr Gerhard Käfer is a pioneer in the development of online legal information systems whose contributions extend back to the first generation of those systems. Germany’s Juris system was one of the world’s earliest high quality legal information systems and retains its reputation for quality today, both in relation to the primary materials of the law, and the doctrine or commentary built on those primary materials. I therefore thought it would be appropriate to provide a contribution on one aspect of how the recent generation of free access legal information systems is starting to approach the question of the integration of primary and secondary legal materials.

Background – Legal Information Institutes

Since the mid-1990s the Internet’s World-Wide-Web has provided the necessary technical platform to enable free access to computerised legal information. Prior to the web there were many online legal information systems, and numerous legal information products distributed on CD-ROM, but there was no significant provision of free access to legal information anywhere in the world. Both government and private sector online legal publishers charged for access. The web provided the key element required for free public access - a low cost distribution mechanism. For publishers it was close to a ‘no cost’ distribution mechanism if they were not required to pay for outgoing bandwidth. The ease of use of graphical browsers from around 1994, and the web’s use of hypertext as its principal access mechanism (at that time) meant that the web provided a simple and relatively consistent means by which legal information could be both provided and accessed, an attractive alternative to the proprietary, expensive and training-intensive search engines on which commercial online services largely relied. The development of free access Internet law services was based on these factors (Greenleaf, 2004). In many countries the first parties to exploit the advantages of the web for providing legal information came from the academic sector rather than government, and did so with an explicit ideology of free access provision (Poulin, 2004; Greenleaf, Mowbray, King and van Dijk, 1995).

Within a few years of the first legal information institute in 1992 the first group of such organisations became known collectively as ‘legal information institutes’ or ‘LIIs’ and those expressions became synonymous with free access to legal information, though in fact they have a narrower meaning than that. Two distinguishing characteristic of the ‘LIIs’ (whether or not they use that name) are that (i) they publish legal information from more than one source (not just ‘their own’ information), for free access via the Internet, and (ii) they collaborate with each other through membership of the ‘Free Access to Law Movement’. Most but not all share other characteristics: they collaborate through data sharing networks or portals, and also through technical networks for security purposes. There are now 22 free access providers sharing these characteristics who are members of the Free Access to Law Movement (Greenleaf, 2008), most of whose data is also accessible through a shared portal, the World Legal Information Institute (WorldLII) <http://www.worldlii.org> .

‘Subject-oriented resources on LIIs – a new opportunity

These Legal Information Institutes were originally few in number (a handful prior to 2000: see Greenleaf, 2008), and their content was limited largely to legislation and decisions. This situation has now changed, and not only because there are over 20 LIIs. Those such as AustLII <http://www.austlii.edu.au> , BAILII <http://www.bailiii.org> , PacLII <http://www.paclii.org> and AsianLII <http://www.asianlii.org> have an increasing wealth and diversity of data. As well as a much larger number of legislation and decisions databases, they increasingly include law reform reports, law journals, treaties and the content of legal scholarship repositories. Most of these resources are generic in their coverage of legal subjects, other than for relatively few subject-specialised tribunals and law journals. New forms of open content commentary are also arising which are likely to be available to LIIs, such as commentary in legal scholarship repositories, in wikis such as Wikipedia and Jurispedia, and in blogs. At present the quality of content from some of these new sources is very variable, but is improving.

So the available LII data is much larger (for example, over 260 databases on AustLII for Australian law alone, and nearly 900 available via WorldLII from all LIIs), and from more diverse sources, but by-and-large its content is generic across all legal subject areas (criminal law, environmental law, tax law etc). It is also not classified into those subject areas, whether by structural segregation, metadata or other means.

Problems of precision of research therefore arise when users try to find material on specific subject matter over such large and rich bodies of data. The sheer number of results retrieved for many subject-oriented searches makes it very difficult and time-consuming for a user to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant results. Relevance ranking of search results can’t solve all of the problems in making searches precise enough. With large numbers of databases now available browsing through tables of contents is also not a feasible option.

The diversity and richness of content on LIIs requires something more than simply a good search engine. Commercial publishers respond to this problem with editorially-controlled subject collections of primary materials, plus commentaries on particular legal subjects (sometimes linked to primary legal materials). Users can then search within the constraints of that collection.

Free access LIIs can’t afford constant editorial interventions, nor commission commentary/doctrine. So the research issue is: How can LIIs create and maintain subject-oriented resources economically?

AustLII is researching the development of ‘subject-oriented libraries’ (‘Libraries’ for short). The key question is ‘what standardised procedures can be developed to create semi-automated Libraries, so as to make this development economical?’. What techniques can be developed that are applicable to a wide range of legal subjects without having to ‘re-invent the wheel’ with every new project? Experimental Libraries are being developed at two levels of scope: over one country’s laws (eg Australian law on AustLII); and over multi-country legal information located on multiple LIIs.

Elements of a subject Library

In the approach we are taking, a Library on any subject can be created from the following components:

(i) Aggregation of existing specialised databases on a subject (usually decisions of Courts or Tribunals, or Law Journals). The more subject-specialised databases are available, the easier it is to start the development of a useful Library. This aggregation alone is not a significant task, though it may be a very useful one.

(ii) Creation of ‘virtual databases’ by extracting / selecting content from existing general databases. A ‘virtual’ database of the selected materials is then created and becomes part of what is searched as part of the Library. Three general methods of selection are possible:

(a) Editorial selection and editorial updating – Reliance on editorial selection re-introduces the same resources issues: LIIs are unlikely to have the editorial staff resources to maintain complex Libraries solely be editorial means. If the editorial burden can be ‘outsourced’ by reliance on the editorial efforts of third parties who are willing to donate them (such as academics who develop teaching resources in an area and thus develop and periodically update lists of key resources), this may make creation of such resources economically feasible, but there will still be questions about whether collections controlled solely by editorial means are comprehensive enough, and whether they can be updated frequently enough. Commercial publishers create useful subject-oriented by this means, but it is an open question whether LIIs can successfully do so.

(b) Search-based selection and automated updating based on repetition of the search – The alternative method of development of sustainable Libraries is to develop virtual databases by search selection so that the costs of development and maintenance can be minimised.

(c) A combination of editorial and search-based methods – Some combination of automated (search-based) and editorial methods may be possible.

AustLII is investigating all three methods but at present concentrating on (b) and looking for ways to use (c). Our emphasis is therefore on search-based methods, which are the main subject of this paper.

(iii) Creation of facilities to extend the scope of the subject-oriented research beyond the content of the LII(s), toward the goal of the most comprehensive possible research on the subject (the ‘one stop shop’ approach). We are utilising four such components in various Libraries:

(a) a Catalog of links to non-LII sites on the subject;

(b) a Websearch of content of those sites only (or as many of them as are searchable), using AustLII’s web spider and search engine;

(c) a ‘Law on Google’ search which converts a search using AustLII’s Sino search engine into the correct syntax for Google search, with terms limiting results to law-related items, and further customised to limit results to those concerning the subject matter and the country/countries involved; and

(d) ‘Publishers’ searches over subject resources of other publishers with whom AustLII collaborates, for easier use by their subscribers (eg IP Library – search over CCH IP Service; Tax Library – search over ATO databases).

Elements (i) and (ii) create the contents of the Library from LII materials, whereas element (iii) goes beyond content available on LIIs. Further details of this third element are in Greenleaf, Chung and Mowbray (2007).

Search-based virtual databases

The following steps allow searches to be used to create and maintain a virtual database where editorial selection of individual items of the contents of the database is impractical:

The result is that a large subject database can be maintained with relatively low editorial input. There are of course editorial inputs here, and they are crucial: the development of the subject search, the determination of the retained percentage, and the periodic revision of both steps. However, these are one-off tasks with periodic revisions, involving a relatively low amount of (preferably high quality) editorial input from subject experts.

Testing search-based methods

Step 2 is the most problematic element in this procedure. The main issue is whether it is possible to have sufficient confidence that the subject search is well-enough constructed that it finds all potentially relevant items which should be included in the Library (ie is comprehensive, or gives maximum recall). Positive validation of the comprehensiveness of a search would require all items which are excluded by the search to be checked for potential relevance, but the content of LIIs is too large for this to be feasible.

We use two methods to increase confidence in comprehensiveness, any one of which can falsify the comprehensiveness of the search:

(1) The subjective opinions of the subject experts as to whether all items that they would expect to find have in fact been found by the subject search is a useful test. If the search does not find all relevant documents that they expect to find (provided they are in the LII), something is wrong with the search. While this is an essential element in development and does give some reassurance, expert opinion has in past studies been shown to be inadequate by itself (Blair and Maron, 1985).

(2) The ‘specialised’ databases excluded from the data used to create the virtual databases can be used as data over which the subject searches may be tested. Their entire content is subject-specific and should be found by the subject search. If the subject search does not retrieve close to 100% of all items in such a database, this indicates that the search may be inadequate. Even 100% retrieval does not prove that a search is comprehensive, because what might work over one database might not be comprehensive in searches over all databases. However, successful testing increases confidence.

A second issue is relating to step 2 is whether the subject search, combined with the relevance ranking algorithm, then ranks the found items in an order such that important items are not wrongly classified as of low relevance and then excluded from the database because they fall in the excluded percentage. This can be dealt with by sufficiently careful checking of items in the proposed excluded percentage by the subject experts.

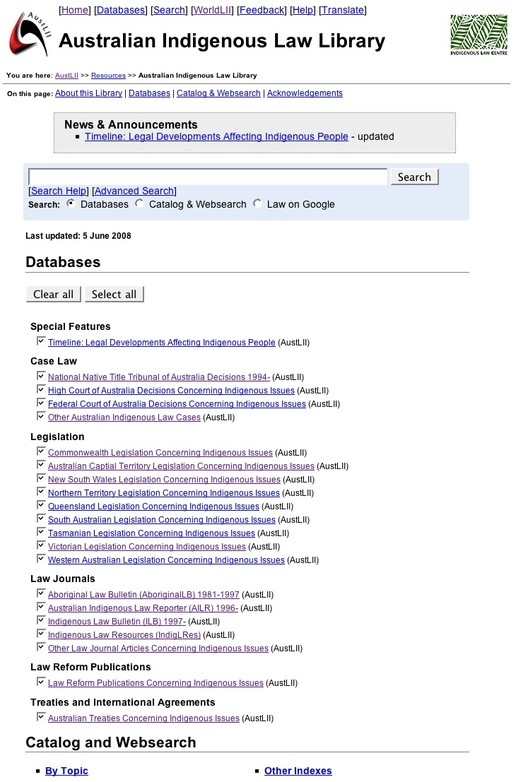

Example: Australian Indigenous Law Library

The Australian Indigenous Law Library at <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/indigenous/> is being developed with subject expertise provided by the Indigenous Law Centre at the University of New South Wales, and funding provided by the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department. It builds upon a previous indigenous law project, the Reconciliation and Social Justice Project (RSJ Project) (1999-2001) developed with the assistance of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation and with Australian Research Council funding (McCann, Greenleaf, Chung and Moore, 2000).

This Library includes in its databases (as shown below) an aggregation of five ‘specialised’ databases, being three law journals (Aboriginal Law Bulletin 1981-1997; Australian Indigenous Law Reporter 1996-; and Indigenous Law Bulletin 1997- ), the decisions of the National Native Title Tribunal, and a large database with very heterogeneous contents called ‘Indigenous Law Resources’.

This last database was developed as a repository for resources gathered during the RSJ Project. It includes documents from 1768-2002 including such major resources as the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody reports (97 volumes), the ‘Bringing Them Home’ Report of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission, and the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation Archive. It also includes the Timeline: Legal Developments Affecting Indigenous People (also listed in the Library’s table of contents as a special feature), and searchable separately.

Australian Indigenous Law Library on AustLII – front page

The Library also includes 15 virtual databases, of which 9 are legislation databases (one for each Australian jurisdiction), two are for the decisions of the two most significant courts dealing with indigenous law issues, one for all the other courts and tribunals, and one each for other law journal articles, law reform publications and treaties concerning indigenous issues. These virtual databases are all developed from expert searches and percentage reductions of results, as described above.

For example, the search developed with our subject expert and used to create the three virtual databases of court and tribunal decisions is:

indigenous or native title or aborigin* or torres strait islanders or stolen generation

The items retrieved are reduced by the expert by 70%, as only 30% are judged to be of sufficient relevance.

When this search is tested over the five specialised databases in the Library, the results (as at 1 July 2008) are:

|

Specialised database

|

Retrieved

|

Total content

|

%

|

|

National Native Title Tribunal

|

2748

|

2748

|

100

|

|

Indigenous Law Bulletin

|

845

|

853

|

99.06

|

|

Australian Indigenous Law Reporter

|

560

|

580

|

96.55

|

|

Aboriginal Law Bulletin

|

985

|

987

|

99.79

|

|

Indigenous Law Resources

|

9642

|

9657

|

99.84

|

|

TOTAL

|

14762

|

14825

|

99.57

|

It seems, therefore, that the search is comprehensive enough to find almost all of the contents in these subject-specific databases, finding 99.37% of all documents. We are yet to find indigenous-related search terms which will improve the results to include the last 0.43%. The addition of clearly relevant search terms to the above subject search, such as ‘black deaths’ or ‘land rights’ or ‘customary law’ makes little difference to the number of items retrieved from these four databases, as the number retrieved increases only from 14762 to 14772 (99.64%). This is a further indication that the search is as comprehensive as may reasonably be expected.

It is however of some use to add these extra terms, as that will improve the performance of the relevance ranking, and therefore improve the outcome of the expert’s decision in step 3 as to what percentage point differentiates the retained and excluded percentages.

There are 28,138 documents retrievable by searches over the Library. A search over the whole of AustLII for the search used (or any of the additional terms)

indigenous or aborigin* or native title or torres strait islander or stolen generation or black deaths or land rights or customary law

retrieves 97,267 items. Only 28.9% of these potentially relevant items are therefore included in the Library. Overall, there is a percentage reduction of 70% to differentiate those items with sufficient relevance to be included in the Library.

Example: Australian Taxation Law Library

The Australian Taxation Law Library <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/special/tax/> has as its project partner the Australian School of Taxation (ATAX) at the University of New South Wales, which provides editorial input into content selection, search formulation and relevance assessment.

The Library includes the aggregation of five specialised databases, all of which are tax and revenue law journals. The other nine databases are virtual databases.

Five virtual databases are developed and updated from subject searches. Four concern case law, from the three main courts and tribunals that make tax decisions, plus ‘Other Australian Cases Concerning Tax’. The other is ‘Other Law Journal Articles Concerning Tax’). The search used to create these databases was developed by ATAX and is:

tax or taxation or gst or capital gains or cgt or fringe benefits or fbt or capital allowance or title(atr) or title(atc) or (tax w/5 (offence or penalty)) or title(revenue) not ((certificate or cost) w/5 taxation )

For all of these databases, ATAX assess that approximately the first 20% of articles found were sufficiently relevant. The virtual databases created by searches are updated daily, as indicated at the top of the Library. Testing of this search is delayed until the databases are amended so that that text that is searched does not include the name of the database.

The three legislation databases developed so far (Commonwealth, NSW and Victorian tax legislation) are created by editorial selection by ATAX. They cover Acts and legislation, but need to be supplemented by Bills and Explanatory Memoranda/Statements.

One other virtual database in this Library is created by editorial selection, namely the ‘Australian Tax Treaties’ database which is created from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT’s) classification of treaties, selecting those which are classified by DFAT as taxation treaties. While this is good up to a point, DFAT only includes treaties in the Australian Treaties Series (ATS), and not any of the other documents leading to the adoption of a treaty, which are also held on AustLII. We are therefore reconsidering how to build this database, possibly by using a search with the DFAT classification then being used as a check for comprehensiveness of the treaties.

Australian Libraries under development on AustLII

A number of subject-oriented Libraries concerning Australian law have been started on the AustLII system since 2003. However, they have been developed at different stages as AustLII’s approach has developed, and do not yet include the virtual databases described herein and used in the Indigenous Law and Taxation Law Libraries. These earlier Libraries (Industrial Law, Intellectual Property Law and Military & Peacekeeping Law) will now be re-developed using this new approach. A number of other Libraries are also under development.

|

Libraries on AustLII

|

Status

|

Funding

|

Expertise / Comments

|

|

Indigenous Law

|

Public

|

Indigenous Law Centre and Cth Att.-General; previous ARC Linkage grant for

CAR Library

|

Re-developed with expertise from Indigenous Law Centre (UNSW).

|

|

Taxation Law

|

Public

|

UNSW RIBG 2007

|

Developed with expertise from ATAX (UNSW)

|

|

Public

|

ARC ‘Unlocking IP’ Linkage Project

|

Being re-developed using virtual databases etc; expertise from UNSW

|

|

|

Public

|

Funding sought for further development

|

Being re-developed using virtual databases etc; expertise sought

|

|

|

Public

|

Department of Defence, 2003–

|

Being re-developed using virtual databases etc; expertise from Defence Dept

and UNSW

|

|

|

Legal History Pre-1900

|

Under development

|

Funding to be sought

|

Being developed with expertise from Macquarie U.

|

|

Constitutional Law

|

Under development

|

UNSW RIBG 2007

|

Being developed with expertise from UNSW Law Faculty.

|

|

Criminal Law

|

Under development

|

UNSW RIBG 2007

|

Being developed with expertise from UNSW Law Faculty.

|

Multi-country subject Libraries – Existing and proposed

Some LIIs aggregate content from many countries (eg PacLII, SAFLII, Droit Francophone; CommonLII, AsianLII, WorldLII), so it is possible in theory to build multi-country subject libraries as well as to just do multi-country searches, provided that cooperation of the various LIIs whose databases are included is obtained. The simplest multi-country Libraries built as yet only aggregate databases of a particular type across countries and LIIs. Examples include the Libraries on WorldLII for Treaties, Law Reform and International Courts & Tribunals . In effect they are the same as ‘Advanced Search’ facilities found on WorldLII and other LII, and are not the subject of this paper.

More complex are international comparative law facilities in specialised subject areas, which involve the same issues concerning development of virtual databases as do subject libraries from one country. As yet there are two Libraries on WorldLII which include virtual databases. Both Libraries aggregate extensive specialised databases, but their utility would be limited (in terms of comprehensiveness) unless they also contained virtual libraries of case law, legislation, law journal articles and other non-specialised content. The Privacy Law Library includes 25 databases, 22 of which are specialised databases on privacy law (18 case law databases from numerous countries and 4 journals, plus three virtual databases by editorial selection (Law Reform, Cases and Legislation). These are now being re-developed to include more use of virtual databases based on subject searches.

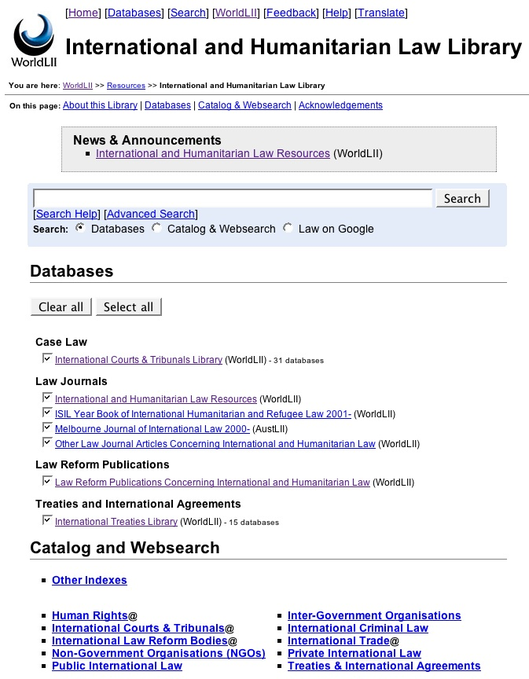

Example: International and Humanitarian Law Library

The International and Humanitarian Law Library on WorldLII[1] includes 46 databases. It is a prototype of a planned larger system (for which ARC LIEF funding has been sought for 2009), developed with assistance from international law colleagues from UNSW Law Faculty. Experts from other Universities are also becoming involved.

The Library contains over 53,000 documents considered to be sufficiently relevant to international and humanitarian law, drawn from the millions of documents searchable via the World Legal Information Institute (WorldLII). The front page of the Library, shown below, indicates its contents, which can be divided into the aggregation of existing databases, and the creation of new ‘virtual’ databases.

The largest content in the prototype Library is from two previous aggregations of existing databases:

(i) the International Treaties Library[2] contains 15 databases[3] hosted on AustLII, AsianLII, NZLII, HKLII, PacLII and CommonLII;

(ii) the International Courts and Tribunals Library[4] contains 26 databases[5] which are mainly hosted on WorldLII (24), but also on BAILII (2)).

Two law journals, and proceedings of a conference (ANZSIL), specialising in international law and human rights are also included.

Front page of International and Humanitarian Law Library on WorldLII

The techniques described above are used to create two ‘virtual databases’ from content in databases on LIIs available via WorldLII:

(i) Other Law Journal Articles Concerning International and Humanitarian Law contains any articles which primarily concern international or humanitarian law in any of the 60+ law journals available via WorldLII[7], which are not specialist international law journals (mainly from AustLII, but also from CommonLII, AsianLII, PacLII and BAILII), or in any of the general legal scholarship repositories[8]. The resulting virtual database includes 4,000 items.

(ii) Other Law Reform Publications Concerning International and Humanitarian Law contains any law reform reports or parts thereof which primarily concern international or humanitarian law, drawn from the 24 sets of law reform reports[9] available via WorldLII, drawn from AustLII, BAILII, NZLII, SAFLII, CommonLII, HKLII and PacLII. The resulting virtual database includes 1,000 items.

At this stage we have made no attempt to develop virtual databases which would attempt to find all national cases and national legislation relevant to international and humanitarian law from any of the over 100 countries whose national cases and legislation are searchable via WorldLII. It may be possible to consider this when the techniques discussed here are more mature.

The search used to create the two existing virtual databases is still being finalised, but the current working version is

unilateral or multilateral or bilateral or protocol or diplomatic or diplomacy or treaty or convention or international or humanitarian or human rights or wto or world trade organi?ation or law of war or law of the sea or law of outer space or space law or military law or peacekeeping or european union or european communities or world bank or league of nations or nato or ilo or refugee or united nations or unesco or genocide or nafta

A search using only the first three terms ‘international or humanitarian or human rights’ produces 10,000 results (for the ‘Other Law Journals’ database), without any percentage reduction. The addition of all the remaining terms only adds another 1,000 results. Addition of further terms (such as the names of additional international organisations) is only likely to add small numbers of additional results, but will improve the relevance ranking.

Testing of the completeness of the search cannot be completed until some of the specialised databases are amended so that the text that is searched does not include the title of the database. However, tests have been done on parts of the Library where this problem does not occur. A test of the search over the 14[10] (of 26) databases in the International Courts and Tribunals Library where this problem does not occur retrieves 4015 documents out of the total of 4024 that they contain, or 99.8% retrieval. A test of the search over the total 124 documents in the Melbourne Journal of International Law database finds all 124 items (ie 100% retrieval). These results give a measure of confidence but cannot be assumed to apply to the whole Library.

The search cannot yet be tested over any of the treaties databases, as they need to be rebuilt to remove the title of the database from the searchable text. Further analysis there may also improve the search. A test of the above search over the whole Library and its 53,100 content items retrieves 52,464 items, or 98.8% of content items. However, such a search over the whole Library is not yet reliable because of the problem mentioned above.

|

Specialised database

|

Retrieved

|

Total content

|

% retrieved

|

|

14 International courts & tribunals

|

4015

|

4024

|

99.8%

|

|

Melbourne Journal of International Law

|

124

|

124

|

100%

|

The two virtual databases are currently reduced to 30% of the items found by the above searches, after those searches are run over all law journals and all law reform reports. The law journals search results are reduced from over 12,000 results to 4,000 items in the virtual database. The law reform search results are reduced from 3,000 results to 1,000 items in the virtual database.

Addition of further very relevant terms to the above search, such as ‘crime against humanity’, ‘law of nations’, ‘torture’, ‘war crime’ or ‘peace conference’, do not result in any additional items being retrieved. However, addition of these terms would improve the relevance ranking of the items retrieved, and thus improve the accuracy of the percentage cut-off.

The 30% cut-off is not finalised. While it gives a reasonable dividing line, our initial assessment is that it is probably somewhat too inclusive for law reform materials and too restrictive for law journals. Further assessments by experts on international and humanitarian law of (a) whether additional search terms would improve the relevance ranking, and (b) whether the cut-off percentages should be raised or lowered for each virtual database, are needed before this aspect can be finalised. However, the inclusion of the 30% cut-off for the time being does not, in our opinion, impede the utility of the Library in any major way.

Further development of international and multi-country Libraries

As with the Australian Libraries on AustLII, the existing and proposed multi-LII Libraries on WorldlII also need to be brought into a consistent format, and to all utilise virtual databases.

|

Library |

Host LII

|

Status

|

Funding

|

Comment

|

|

WorldLII

|

Public

|

ARC ‘Interpreting Privacy Principles Discovery 2006-09

|

25 databases; being re-developed using virtual databases etc

|

|

|

WorldLII

|

Public

|

DFAT (Treaties Library); UNSW RIBG 2007; prototype for 2009 ARC LIEF grant

|

51 databases; prototype developed with expertise from UNSW Law

Faculty

|

|

|

Criminal Law Library

|

CommonLII

|

Proposed

|

Commonwealth Secretariat has approved funding

|

Criminal law in Commonwealth countries

|

Further research

This paper sketches a low-cost method by which free access legal information institutes may build and maintain subject-oriented resources. Various elements of the method are not yet sufficiently explored, particularly those relating to the development and testing of subject searches, and further research on these matters is needed. Nevertheless, the feedback from subject experts (including those involved in developing the Libraries) is that the utility of the approach is already sufficient to make the Libraries worth using, in preference to starting research over the LII’s content as a whole. We are therefore continuing to develop the ideas behind the Libraries, and giving them some limited deployment in Libraries available to users.

References

Blair and Maron (1985) – Blair, DC and Maron ME ‘An evaluation of retrieval effectiveness for a full-text document-retrieval system’ Communications of the ACM, Volume 28, Issue 3 (March 1985), pgs 289 – 299

Greenleaf (2008) – Greenleaf, G ‘Legal Information Institutes and the Free Access to Law Movement’ GlobaLex, February 2008 at <http://www.nyulawglobal.org/globalex/Legal_Information_Institutes.htm>

Greenleaf (2004) – Greenleaf G 'Jon Bing and the History of Computerised Legal Research – Some Missing Links' in Torvund O and Bygrave L (Eds) Et tilbakeblikk på fremtiden ("Looking back at the future") 61-75, Institutt for Rettsinformatikk, Oslo, 2004 available at <http://www2.austlii.edu.au/~graham/publications/2004/Greenleaf_Bing_book.pdf>

Greenleaf, Chung & Mowbray (2007) – Greenleaf G, Chung P & Mowbray A ‘Data mining free access to law for doctrine’ (PPTs) 8th Law via Internet Conference, Montreal, October 2007

Greenleaf, Chung and Mowbray (2007a) – Greenleaf G, Chung P, and Mowbray A ‘Emerging Global Networks for Free Access to Law: WorldLII’s Strategies 2002-05’ (2007) 4(4): 319-366 SCRIPT-ed, University of Edinburgh, ISSN 1744-2567 at <http://www.law.ed.ac.uk/ahrc/script-ed/vol4-4/greenleaf.asp>

Greenleaf, Mowbray, King and van Dijk (1995) – Greenleaf G, Mowbray A, King G and van Dijk P, "Public access to law via internet: the Australasian Legal Information Institute", Journal of Law & Information Science, 1995, Vol 6, Issue 1 at <http://www.austlii.edu.au/austlii/articles/libs_paper.html>

McCann S, Greenleaf, G, Chung P and Moore T, (2000), "Reconciliation Online: Reflection and Possibilities",The Journal of Information, Law and Technology (JILT), vol 2, 2000 at <http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/law/elj/jilt/2000_2/mccann>

Poulin (2004) – Poulin D ‘Open Access to Law in Developing Countries’ First Monday Vol. 9, No 12, 6 December 2004 at <http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue9_12/poulin/index.html>

[*] Published in in Helmut Rüßmann (Ed) Festschrift für Gerhard Käfer, pgs 75-94, Juris GmbH Saarbrücken, 2009

[**] Graham Greenleaf is Professor of Law, University of New South Wales, and Co-Director of the Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII); I would like to thank my AustLII Co-Directors Philip Chung and Andrew Mowbray for their contributions to this ongoing research; our academic colleagues who have acted as subject experts in the development of Libraries; to Bridgett McDermott for input into all aspects of the Indigenous Law Library, and to Pierre-Paul Lemyre for suggestions on testing the comprehensiveness of search results.

[1] <http://www.worldlii.org/int/special/ihl/>

[2] http://www.worldlii.org/int/special/treaties/>

[3] APEC Agreements and Declarations (AsianLII); ASEAN Agreements and Declarations (AsianLII); Australian Treaties Series (ATS) (AustLII); Australian Treaty List - Monthly Updates (AustLII); Australian Treaties Not yet In Force (ATNIF) (AustLII); Joint Standing Committee on Treaties (JSCOT) Reports (AustLII); Australian Select Documents on International Affairs (AustLII); Australian National Interest Analyses (ATNIA) (AustLII); List of Multilateral Treaty Actions Under Negotiation or Consideration (AustLII); Hong Kong Treaties Index (HKLII); New Zealand Treaty Series (NZTS) (NZLII); Pacific Islands Treaty Series (PacLII); Status Lists for Multilateral Treaties for which Australia is Depository (AustLII); Singapore Treaties (CommonLII); Treaty Law Resources (AustLII)

[4] <http://www.worldlii.org/int/cases/>

[5]6 Central American Court of Justice Decisions 2003-; Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) Court of Justice Decisions 2001- ; Court of Justice of the Andean Community Decisions 1985- (WorldLII); Commission of the European Communities Decisions 2003- (WorldLII); European Committee of Social Rights Decisions 1999-; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Decisions 1996-; Inter-American Court of Human Rights Decisions 1981- (Selected); International Court of Justice Decisions 1993- ; International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Decisions 2004-; International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia Decisions 1996- (WorldLII); International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea Decisions 1997- (Selected); North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA) Decisions 2004- ; Permanent Court of Arbitration Decisions 1905- (Selected); Permanent Court of International Justice Decisions 1922-1946 (Selected); World Trade Organization Appellate Body Decisions 1996-; World Trade Organization Arbitrators Decisions 1998-; World Trade Organization Panel Decisions 1998-; United Nations Committee against Torture Decisions 1993-; United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Decisions 1988-; United Nations Human Rights Committee Decisions 1977-; United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women Decisions 2004-

[7] See <http://www.worldlii.org/int/journals/>

[8] Including those drawn from the 25,000+ articles in SSRN’s Legal Scholarship Network (LSN) and 3,000+ in the bepress Legal Repository.

[9] <http://www.worldlii.org/int/special/lawreform/> (24 databases in the Law Reform Project)

[10] The 14 are (1) UN related - UNCAT, UNCERD, UNHRC; (2) WTO related - WTOAB, WTOARB, WTOP; (3) Int Criminal tribunals - ICJ, ICTR, ICTY; (4) Inter-American - IACommHR, IACHR; (5) Other trade related - ITLOS, ECComm, NAFTA.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ALRS/2009/19.html