ALTA Law Research Series

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

ALTA Law Research Series |

|

Last Updated: 16 September 2011

Latest Developments in SMEs Officers’ Duties

Professor Michael Adams[1], School of Law, University of Western Sydney

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the balance between officers’ and directors’ duties in the context of modern regulatory reform. The onus that falls on all directors from a legal point of view is irrespective of the size and complexity of the corporation. Thus, a small (micro-business) with a single director has the same legal obligation under the common law, the equitable fiduciary duties and the statutory obligations under the Corporations Act. The current Federal Government is attempting to reduce the burden of red tape on business and the regulators, in particular ASIC, are pursuing cases to enforce the law. There has been recent cases law which helps explain the key statutory provisions of the complexity of the law. The major defence and protection for officers’ duties, the so called “business judgement rule” does not seem very effective and quality insurance cover is probably much more useful in the commercial world.

Introduction

The last twenty years has seen the rise of a new Federal regulator, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) to promote and enforce the major legislation – the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). In that period, 1991 until 2011, the regulator, ASIC, has had a mixed level of success in the area of enforcement, both against corporate bodies and the individual directors and officers.[2] This paper examines the impact of the regulator on officers’ (directors’) duties as applied across all companies (including small to medium size enterprises). In particular, ASIC and the the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (CDPP) have always claimed a high success rate in litigation. However, where the litigation, whether civil, civil penalty or criminal has been contested, the results have not been so positive, In fact, ASIC has in the last 12 months lost three very high profile cases, which has undermined the confidence of the regulator. It is worth noting that officers’ duties are the same laws for all companies, irrespective of the size and complexity of the company. Obviously, if a corporation is also listed on a securities exchange, such as the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), there are additional legal responsibilities for officers.

It is worth noting that legal term “officer” is defined in s 9 (Dictionary) Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) as:

(a) a director or secretary of the corporation; or

(b) a person:

(i) who makes, or participates in making, decisions that affect the whole, or a substantial part, of the business of the corporation; or

(ii) who has the capacity to affect significantly the corporation's financial standing;

In most cases the majority of officers of a corporation are the directors, but it does include the chief executive officer (CEO) and possibly the chief financial officer (CFO) and other senior executives, depending upon the size and structure of the corporation. In a small corporation it is likely to only be the director(s) and CEO. The Royal Commission into the collapse of HIH Insurance recommended the change of definition of officer from “executives” to this more functional approach to an officer.

The Corporations Act also has a definition of “director”, which is also found in s 9 (Dictionary) as:

(a) a person who:

(i) is appointed to the position of a director; or

(ii) is appointed to the position of an alternate director and is acting in that capacity;

regardless of the name that is given to their position; and

(b) unless the contrary intention appears, a person who is not validly appointed as a director if:

(i) they act in the position of a director; or

(ii) the directors of the company or body are accustomed to act in accordance with the person's instructions or wishes.

In 99% of cases, it is very clear who is an officer of a company, as it includes all the directors and the company secretary (if appointed). In small corporations, the CEO or managing director is nearly always a registered director, but even if he or she is not, they would be deemed to be an officer of the company and thus bound by the same laws.

The officers of the company have very well defined legal obligations and there is a clear link to the role of corporate governance in al entities. Over the last decade corporate governance and in particular the role of officers’ duties has closely come under the microscope of the courts in all jurisdictions. No director, company secretary, general counsel or chief financial officer could argue they did not know what is expected of them in terms of the basic legal duties owed to the company. The HIH Insurance Royal Commissioner, the Hon Justice Neville Owen, in May 2008, re-stated the need for a commitment to education on the fiduciary principle and for greater professionalism in governance.

This paper builds on some earlier published work on directors and officers’ duties in the journal of Chartered Secretaries Australia, Keeping Good Companies by the author.[3] The Federal Minister responsible for developments in this area of law has noted that a review into the Safe Harbour Rule (known as the Business Judgment Rule[4]) in the Review of Sanctions in Corporate Law (2007) paper, did not expect any quick changes at the moment. This is very true statement, as there has been no change to this officers’ defence and few directors have ever been able to successfully rely upon it as a defence. The details of the business judgment rule are discussed below.

It is fair to say that any lay person might feel confused over the state of Australian corporate law. This is sharply brought into focus for directors and company officers that have an increasingly high expectations imposed upon them by a number of stakeholders.

As the author has previously identified the following statement by Sir Anthony Mason CJ wrote in 1992 that “Oscar Wilde described fox-hunting as “the unspeakable in full pursuit of the uneatable”. Oscar Wilde, the supreme stylist, would have regarded our modern Corporations Law not only as uneatable but also as indigestible and incomprehensible.”[5]

Background

ASIC[6] has been the primary regulator for corporations since the inception of the national legislation in 1991. The ASIC Annual Reports provide some useful data for comparative purposes and to set a back ground to the discussion on officers’ duties.

|

Event

|

1991

|

1995

|

1998

|

2001

|

2006

|

2010

|

|

Total no

|

892,749

|

933,652

|

1,088,192

|

1,224,207

|

1,480,684

|

1,768,526

|

|

New incorps.

|

n/a

|

82,278

|

97,031

|

76,103

|

121,298

|

157,667

|

|

Private (Pty)

|

871,648

|

915,437

|

1,070,050

|

1,188,042

|

1,392,458

|

1,738,638

|

|

AFSL

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

35

|

4,415

|

4,874

|

|

Auditors

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

7,222

|

5,848

|

5,270

|

|

Fundraising prospectuses

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

683

|

2,744

|

808

|

880

|

|

Takeovers

|

n/a

|

96

|

76

|

81

|

60

|

73

|

This table shows there has been a steady increase in the number of companies registered each year and that the total number of proprietary companies (which are mostly classified as small to medium enterprises) make up over 98% of all companies incorporated. It is interesting to note the annual number of companies incorporated has increased dramatically over the 20 years, whereas the registered auditors, prospectuses and takeovers have remained relatively stable. Small corporations are not required to have auditors, are prohibited from issuing fundraising documents (prospectuses) and are not involved in takeovers (under the Corporations Act).

The next table looks at the regulator and how it has changed over the two decades.

|

ASIC

|

1995

|

1998

|

2001

|

2006

|

2010

|

|

Operating rev

|

$145m

|

$131m

|

$144m

|

$225m

|

$381m

|

|

Fees to Cth

|

$258m

|

$335m

|

$363m

|

$543

|

$582m

|

|

Total equity

|

$9.7m

|

$1.6m

|

$2.2m

|

$7m

|

$117m

|

|

Staff (FTE)

|

1,551

|

1,152

|

1,221

|

1,471

|

1,932

|

|

Searches

|

n/a

|

2.2m

|

7m

|

45m

|

61m

|

|

Compliance

|

84%

|

94%

|

93%

|

94%

|

95%

|

One of the key areas of note is the enforcement aspect of ASIC, both directly and in conjunction with the Commonwealth DPP. The table below gives a useful snap-shot.

|

ASIC

|

1995

|

1998

|

2001

|

2006

|

2010

|

|

Jailed

|

12

|

26

|

25

|

17

|

12

|

|

Successful

|

81%

|

90%

|

71%

|

94%

|

91%

|

|

Litigation

|

74

|

199

|

150

|

386

|

156

|

|

Reports of misconduct

|

7,287

|

7,509

|

6,946

|

12,075

|

13,372

|

|

Dollars recovered

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

$121m

|

$215m

|

$302m

|

In the last decade, sending corporate officers to jail has been a steady stream averaging 22 directors and officers per year. The ten years from 2000 until 2010 shows 220 officers were sent to jail in Australia. The highest year was in 2000 with 25 jailings and the lowest was in 2004 with 27 jailings. The successful litigation percentage includes contested and uncontested cases, in both civil and criminal cases.

Focus on small corporations

Over the 20 years of ASIC regulation,

the Federal Minister who has been responsible has changed from government to

government. Currently,

the Hon Wayne Swan MP as Commonwealth Treasurer

has responsibility for “corporate and securities law”. Whereas,

within the Department of Treasury, the Hon David Bradbury

MP, as Parliamentary

Secretary to the Treasurer, is actually responsible for ASIC and corporate

governance. Then, the Hon Bill Shorten

MP, as Assistant Treasurer and Minister

for Financial Services and Superannuation, also has some corporate law

responsibilities.

However, it is the Hon Nick Sherry, who is the Minister for

Small Business and has been recently making a number of announcements.

Senator Sherry[7] noted that the Department of Finance has been conducting a review to reduce red tape across the business sector. The review has found that 11,444 regulations have come under scrutiny and 4,214 are in fact redundant! This means 499 regulations can be repealed by government departments and agencies. A further ten statutes can be removed and 3,715 provisions by way of Parliament passing the necessary amendments.

There has been a particular focus on 27 priority areas, which focus on harmonisation between state and federal jurisdictions, which impact on businesses. It is believed that cutting ten of the 27 areas will result in savings of $3.5 billion across the economy, with $1.8 billion benefiting business. The key success to such reform is the role of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), which has historically had a mixed result in making such changes. The Federal government has provided up to $550 million to tackle the 27 priority areas including national reform of occupational health and safety (OHS), consumer credit, consumer protection, environmental assessment, rail safety, energy market regulation, national transport and infrastructure reform.

The Small Business website (www.business.gov.au)[8] has been seen as a great success and after 12 months has clocked up over 250,000 downloads of its business guides and templates. This is a useful resource, but does not cover any legal aspects relating to officers’ duties (although other laws are generally covered, including OHS and intellectual property).

The Minister for Small Business has noted that Australia has been ranked in the top ten out of 183 economies for starting a business by the World Bank.[9] The report, Doing Business 2011[10]actually placed Australia second in the world to start a business due to the short time, low cost and few administrative procedures required. Australia also ranked highly in getting credit and the ease of doing business. But Senator Nick Sherry has noted that the two million small businesses could be helped even more and he sees the COAG National Partnership to deliver a “Seamless National Economy” as a crucial aspect. One practical way has been the government’s provision of $42.5 million to 37 Business Enterprise Centres to help over 182,000 businesses. The tax benefits for small companies from July 2012 and the instant write-off of assets under $5,000 will be a great help.

The cutting of red tape will always be easy to say but harder to deliver, but the focus on simpler national business name registration (with the three year fee moving from $1,000 to just $70) and improved trademark searching. The biggest help is probably the developments in “standard business reporting” (SBR) which has involved the governments with 30 software developers and the acceptance of Auskey for time-saving new digital security certification to transmit data from business to the Government online. It is projected that the full implementation of SBR could save businesses $800 million annually. Other areas of reform for small business are loan and credit reform to cut the cost of capital/finance and the introduction of the Personal Property Security Act 2009 (Cth) from October 2011. This will make it much easier for businesses to take secured loans and guarantee the repossession of goods where a customer fails to pay. Deloitte Access Economics have predicted that these reforms could cut the cost of small business borrowing in Australia by 3%.

Australian Officers Duties Guides

The Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) in s 111J contains a “Small Business Guide” which outlines in plain English the various legal obligations of setting up and running a company. In Section 1 and Section 5 of the Small Business Guide it informs about the appointment of directors and their basic legal duties. For convenience this is reproduced:

1 What registration means

1.8 Directors

The directors of a company are responsible for managing the company's business. It is a replaceable rule (see 1.6) that generally the directors may exercise all the powers of the company except a power that the Corporations Act, a replaceable rule or a provision of the company's constitution (if any) requires the company to exercise in general meeting.

The only director of a company who is also the only shareholder is responsible for managing the company's business and may exercise all of the company's powers.

The Corporations Act sets out rules dealing with the calling and conduct of directors' meetings. Directors must keep a written record (minutes) of their resolutions and meetings.

There are 2 ways that directors may pass resolutions:

• at a meeting; or

• by having all of the directors record and sign their decision.

If a company has only 1 director, the sole director may also pass a resolution by recording and signing their decision.

[sections 198A, 198E, 202C, subsection 202F(1), sections 248A- 248G, 251A]

5 Company directors and company secretaries

5.1 Who can be a director

Only an individual who is at least 18 years old can be a director. If a company has only 1 director, they must ordinarily reside in Australia. If a company has more than 1 director, at least 1 of the directors must ordinarily reside in Australia.

A director must consent in writing to holding the position of director. The company must keep the consent and must notify ASIC of the appointment.

In some circumstances, the Corporations Act imposes the duties and obligations of a director on a person who, although not formally appointed as a director of a company, nevertheless acts as a director or gives instructions to the formally appointed directors as to how they should act.

The Court or ASIC may prohibit a person from being a director or from otherwise being involved in the management of a company if, for example, the person has breached the Corporations Act.

A person needs the Court's permission to be a director if the person has been convicted of certain offences or is, in some circumstances, unable to pay their debts as they fall due.

Generally, a director may resign by giving notice of the resignation to the company. A director who resigns may notify ASIC of the resignation. If the director does not do so, the company must notify ASIC of the director's resignation.

[sections 9, 201A, 201B, 201D, 205A, 205B and 206A-206G, 228-230 and 242 and subsection 1317EA(3)]

5.2 Appointment of new directors

It is a replaceable rule (see 1.6) that shareholders may appoint directors by resolution at a general meeting.

[section 201G ]

5.3 Duties and liabilities of directors

In managing the business of a company (see 1.7), each of its directors is subject to a wide range of duties under the Corporations Act and other laws. Some of the more important duties are:

• to act in good faith

• to act in the best interests of the company

• to avoid conflicts between the interests of the company and the director's interests

• to act honestly

• to exercise care and diligence

• to prevent the company trading while it is unable to pay its debts

• if the company is being wound up--to report to the liquidator on the affairs of the company

• if the company is being wound up--to help the liquidator (by, for example, giving to the liquidator any records of the company that the director has).

A director who fails to perform their duties:

• may be guilty of a criminal offence with a penalty of $200,000 or imprisonment for up to 5 years, or both; and

• may contravene a civil penalty provision (and the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth an amount of up to $200,000); and

• may be personally liable to compensate the company or others for any loss or damage they suffer; and

• may be prohibited from managing a company.

A director's obligations may continue even after the company has been deregistered.

[Sections 180, 181, 182, 183, 184, 475, 530A, 588G, 596, 601AE, 601AH, 1317H]

The Australian Government’s reform body for corporate law, the Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee (CAMAC) in April 2010 published a more detailed guide to directors.[11] This report outlines in detail the challenges for directors and the various guidance to be drawn from legislation, the case law, the regulators and the ASX Corporate Governance Council. It also provides an international comparison with the United Kingdom and North America. The report is a useful resource for public companies and those listed on the ASX rather than smaller entities.

Before examining the recent developments in Australian case law of officers and in particular director’s duties, it is valuable to review the existing laws. There is a natural overlap between the legislation imposed by Parliament and the case law developed over the last couple of centuries. Companies have existed since 1600[12] but the modern incorporated (registered) company can be identified since 1844.[13] Australia has mostly followed the corporate laws of the United Kingdom and moved to registered corporations as part of the move in 1991 to a national system, under what is now the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

Overview of Officers and Directors’ Duties in Australia

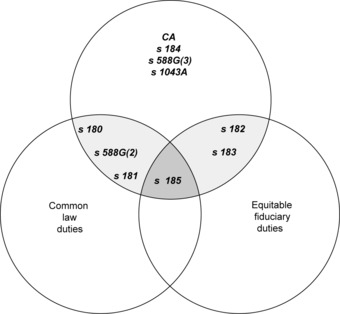

In Australia, the law relating to officers and directors can be divided into three:

• Statutory duties

• Common law duties (such as the duties of care, skill and diligence)

• Equitable fiduciary duties.

The fundamental duties that are imposed on all officers of all companies can be illustrated in a Venn diagram. The overlapping areas represent how the Corporations Act 2001 in Part 2D.1 reflects parts of the common law and equitable principle.

Figure 1: Overview of officers’ duties[14] (Adams, 1992 - updated)

Some duties are specifically laid out in statute, such as insider trading in s 1043A. Other duties, such as when directors have interests in company contracts, are both statutory (s 191) and fiduciary duties. Directors must not trade while insolvent by s 588G and have a common law duty to consider creditors in times of financial trouble, as in the High Court of Australia case of Spies v R [2000] HCA 43.

Where the three circles intersect represents s 185 which provides that the duties imposed by legislation are additional to the duties imposed at common law and in equity, rather than exclusive of them. Thus a director could be sued for all three actions rather than just the Corporations Act or the common law/equity principles. An example of a director being held liable for all three types of actions occurred in South Australia State Bank v Clark (1996) 16 ACSR 606.

A breach of ss 180–183 may result in a civil penalty order under s 1317E but this is not applied under the common law or equity. However, further criminal liability may also arise under s 184 in relation to the types of breaches found in ss 181–183.

However, it is worth noting that at common law officers are expected to be honest and to take reasonable care in exercising their duties. At the same time, s 181 provides that officers are required to discharge their duties in good faith and for a proper purpose, whilst s 180(1) provides that they must do so with reasonable care and diligence. Also, the equitable principles of avoiding conflicts of interest and not taking advantage of confidential information are reflected in both ss 182 and 183.

Working professional directors and officers (as well as the many non-executive and part-time directors) have difficulty with keeping up-to-date with the many cases surrounding the same factual circumstances, but deal with different aspects of the law. For example the OneTel litigation, which is often cited as the ASIC v Rich [2003] NSWSC 85 involves many different sub-cases. Obviously, the HIH litigation and the GIO litigation, all produced many cases surrounding the directors’ duties. In the future, the 2007-2008 collapses of Opes Prime brokers’ litigation and Centro shopping centres, will produce multiple cases to confuse directors and company secretaries.

One of the most significant decisions was the ASIC v Rich (known as the “Greaves One.Tel” case) which occurred in 2003, as it examined the precise role of a chairman of the collapsed tele-communications company, One.Tel. Mr Greaves was held to have been a paid non-executive director with finance experience and thus owed a higher duty of care under the common law and statute than other directors by Justice Austin. This original case was a procedural action which was to be struck out, went on to an out-of-court settlement for $20 million, which was paid to the liquidator. This settlement plus an agreed banning order had to be formally certified by Justice White and thus gives legal status to the earlier decision of Justice Austin in the NSW Supreme Court. Unfortunately, the final case of Jodee Rich did not work out positively for ASIC in 2009. Before detailing the failed litigation of ASIC, it is important to note the limited success in the James Hardie litigation and other major cases.

The High Court of Australia does not often examine corporate law cases, but one of the many One.Tel cases, Rich v ASIC [2004] HCA 42[15] examined the importance of procedures in the area of civil penalties. The HIH Insurance cases around ASIC v Adler, Williams & Fodera [2002] NSWSC 171 examines in depth the civil penalty standards of directors’ duties. In particular whether Mr Rodney Adler acted honestly (a breach of s181) and taking reasonable care and diligence (a breach of s 180) by Mr Ray Williams and Mr Adler. Unusually, was a separate criminal prosecution was launched against Mr Williams[16] and Mr Adler[17], resulting in a conviction and jail sentence. This was followed by the high profile case of Steve Vizard for using confidential information from the boardroom of Telstra for personal gain.[18] This case could have been brought under the insider trading laws, but was in fact brought under the directors’ duties provision for misusing confidential information.

Hot on the heels of the HIH Insurance cases was the GIO cases (the hostile takeover by AMP of GIO) which resulted in ASIC v Vines, Robertson & Fox [2005] NSWSC 738 (22 August).[19] This case held the three CFOs of the various GIO companies liable for a breach of their duties as officers of the target company. A higher duty of care had been expected of a chair of a company or even a board audit committee following Hall v Poolman [2007] NSWSC 1330.

Thus, after a number of successes against directors in the civil and criminal courts, ASIC potentially hit a wall. The initial highs of the successful 2009 James Hardie litigation[20] has resulted in an appellant court over-ruling Justice Gzell in a number of ways and exonerating most of the directors held liable. The case of Morley v ASIC [2010] NSWCA 331 (17 December) and James Hardie Industries NV v ASIC [2010] NSWCA 332 (17 December) was a huge step backwards for the regulator. The outcome of the appeal was that mixed in that the company (JHL) did make misleading statements to the ASX in June 2002 and failed to comply with continuous disclosure. The CFO at the time, Mr Morley, was in breach of his duty in advising the board and limited nature of the predicted analysis of compensation. Similarly, the company secretary and general counsel, Mr Shafron, had part of his appeal upheld, but still in breach of his duty to advise the board. The other non-executive directors, including the chair, Ms Hellicar, were successful with their appeals and breaches of the officers’ duty in s 180 were removed, in respect of the approved minutes of the board meeting (which became the ASX announcement on asbestos compensation). ASIC was criticised for not calling a particular witness (an external lawyer) who was present at the relevant board meeting of JHL.[21] This case is not yet over as on 14 January 2011, ASIC applied to the High Court of Australia for special leave to appeal the decision of the NSW Court of Appeal![22]

Losing High Profile Cases

In the last twelve months ASIC has lost a number of high profile cases, including the One.Tel (Jodee Rich case), the AWB case (against CEO Andrew Lindberg) and the Fortescue Metals case (against the CEO Andrew Forrest). As with any paper, it must be noted that the law does not stand still and there are various levels of appeal occurring for all these cases.

The One.Tel case resulted from the collapse of the tele-communication company in 2004. The final decision was handed down by Justice Austin in the NSW Supreme Court in late 2009 in ASIC v Rich [2009] NSWSC 1229 (18 November). The two managing-directors, Mr Jodee Rich and Mr Mark Silberman were found not to have breached their officers’ duties. The cost of the defence was $15 million, which must be paid by ASIC. Two other former directors of One.Tel, Mr Bradley Keeling and Mr John Greaves, settled out of court and thus have bans imposed upon them for ten years and four years respectively.

Probably one of the most important current cases involved the entrepreneur and miner, Mr Andrew Forrest and his listed company, Fortescue Metals Group Ltd (FMG). Mr Forrest, on behalf of FMG announced through media releases and ASX announcements a “binding agreement” with Chinese state-owned corporations to develop the Pilbara region of Western Australia for iron ore exploration. From August 2004 until November the share price rose from 59 cents to $1.93 and by March 2005 a high of $5.05 per share. The Australian Financial Review newspaper investigated the claims of the binding agreement and the price started to drop (once the agreements were disclosed to the ASX). ASIC started proceedings against the company, FMG, for misleading statements and failing to properly comply with continuous disclosure. In addition, Mr Forrest was alleged to have breached his officers’ duty of reasonable care under s 180 Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). The Federal Court found that there was no breach of the Act in ASIC v FMG [No 5] [2009] FCA 1586 (23 December).

ASIC decided to appeal the decision of the trial judge, Justice Gilmour and were successful on all counts in ASIC v Fortescue Metals Group Ltd [2011] FCAFC 19 (18 February). The actual penalty imposed on FMG for the breach of misleading conduct (s 1041H) or the continuous disclosure (s 674(2)) or personally for Mr Forrest for the officers’ duty of reasonable care (s 180(1)) and involvement with a breach of continuous disclosure (under s 674(2A)) has not yet been determined.[23]

Business Judgement Rule

The American developments of corporate law have finally refined what is known as the “safe harbour rule” for directors. This means that if a director makes an honest decision, which with the benefit of hindsight appears to be negligent, then the director is protected from legal action by the company or its shareholders (a class action). In Australia this common law principle[24] was deemed to be too vague and a statutory formulation was created in what is now s 180(2) and re-named the “business judgment rule”.[25]

Section 180 states:

(2) A director or other officer of a corporation who makes a

business judgment is taken to meet the requirements of subsection (1),

and

their equivalent duties at common law and in equity, in respect of the judgment

if they:

(a) make the judgment in good faith for a proper purpose; and

(b) do not have a material personal interest in the subject matter of

the judgment; and

(c) inform themselves about the subject matter of

the judgment to the extent they reasonably believe to be appropriate; and

(d) rationally believe that the judgment is in the best interests of

the corporation.

The director's or officer's belief that the judgment is in the best interests of the corporation is a rational one unless the belief is one that no reasonable person in their position would hold.

Although this looks like a useful and practical protection for officers and directors, in reality it has been rarely successfully used in any case! The few cases it has been applied, the directors in question have failed the “material personal interest” test.[26]

Conclusion

It is important to note that many of the principles of law discussed above can be derived from the general or basic law duties which were borrowed by way of an analogy of the trustees’ duties owed to the beneficiaries, from 1853 in Re German Mining Co; ex parte Chippendale.[27] Although the Corporations Act in many ways codifies the common law and equitable duties, there is still an overlap and have different outcomes in terms of remedies or sanctions.

ASIC must take risks with litigation, as it is the only way to really test the statutory provisions of the complex Corporations Act. However, there is a publicity risk when the regulators lose a major case, but proper case preparation is crucial.

Although many of the cases mentioned in this paper focus on the large ASX listed companies and their officers and directors, the principles are applied to all corporations. The burden of regulation on a director of a small company is huge as they do not normally have the financial resources to fight a big complex case against ASIC or any of the other regulators, such as the Australian Taxation Office or the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. Good corporate governance principles are valuable for all entities.[28]

It is essential that all officers, in respect of all size of corporations understand the role of insurance (particular the specialist policies for directors and officers insurance known as “D&O” policies). It is D&O insurance that plays a significant role in how directors’ cases are run out in the courts. It is critical to remember that insurance does not cover the outcome of a criminal prosecution nor civil penalties, as a matter of public policy and statutory intervention. It may help towards the legal defence costs, but not a penalty for an adverse finding in a case. All officers and directors are advised to keep a careful watching brief on the ever changes currents of litigation. The general duties of honesty and diligence will never change for professional officers for every company in Australia.

[1] Professor Michael Adams is the Head of School of Law at the University of Western Sydney and any comments may be emailed to: Michael.Adams@uws.edu.au

[2] For a detailed discussion of the regulation of small corporations, see Michael Adams “20 year snap-shot of the developments in the regulation of small corporations” (2009) 4(4) Journal of Business Systems, Governance and Ethics 7.

[3] Michael Adams “Are all directors created equal? Reassessing the role of the chair in the light of ASIC v Rich” (2003) 55 Keeping Good Companies 204, Michael Adams “Officers’ duties under the microscope” (2005) 57 Keeping Good Companies 516 and Michael Adams “Officers’ duties –are we keeping up with the changes?” (2008) 60 Keeping Good Companies 344.

[4] Section

180(2) Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)

[5] Anthony Mason “Corporate law: The challenge of complexity” (1992) 2(1) Australian Journal of Corporate Law 1.

[6] Originally the regulator was the Australian Securities Commission (ASC) until its jurisdiction for financial services was increased in July 1998 and the name changed to ASIC.

[7] Senator Nick Sherry in his capacity as Minister Assisting on Deregulation announced in a Media Release “Repeal of redundant regulations dating back to Treaty of Versailles” on 30 March 2011.

[8] Senator Nick Sherry in his capacity as Minister for Small Business in the Media Release “business.gov.au reaches downloads milestone” on 5 April 2011.

[9] Nick Sherry “Repeal Address to Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry General Council” Hotel Intercontinental, Sydney on 31 March 2011.

[10] World Bank

& International Finance Corporation Doing Business 2011: Making a

difference for entrepreneurs World Bank, 4 November

2010.

[11]

Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee, Guidance for Directors

Report, CAMAC

2010

[12] The

Honourable East India Company, 1600

England

[13]

Joint Stock Companies Act 1844 (UK)

[14] Jason Harris, Anil Hargovan, Michael Adams, Australian Corporate Law, 2nd edition 2009, LexisNexis:Butterworths 439.

[15] For a

detailed discussion on this case, see Michael Adams “Whether to protect or

punish: legal consequences of contravening

the Corporations Act” 56

Keeping Good Companies

592.

[16] R

v Williams [2005] NSWSC 315 (15

April).

[17] R

v Adler [2005] NSWSC 274

(

[18] ASIC v

Vizard [2005[ FCA 1037 (28 July)

[19] For a detailed discussion of this case, see: Michael Adams “Officers’ duties under the microscope” (2005) 57 Keeping Good Companies 516.

[20] ASIC v MacDonald (No 11) [2009] NSWSC 287 (23 April) and penalties imposed at ASIC v MacDonald (No 12) [2009] NSWSC 714 (20 August)

[21] More detailed discussions at Anil Hargovan “Directors’ and officers’ duty of care following James Hardie” 61 Keeping Good Companies 586 and Richard Head “Directors and officers still in the firing line – a guide to managing risk” 62 Keeping Good Companies 57

[22] ASIC, “ASIC applies for special leave to appeal James Hardie decision” ASIC Media Release 11-07MR (14 January 2011)

[23] The Full

Bench of the Federal Court has sent the matter of penalties to a single judge of

the Federal Court for determination. There

is a possibility that Mr Forrest and

FMG may appeal the decision to the High

Court!

[24]

Harlowe’s Nominees PL v Woodside (Lakes Entrance) Oil NL [1968]

HCA 37

[25] Kristyn Briggs and Evan Richards “Time for a new business judgment rule?” 60 Keeping Good Companies 288

[26] ASIC v

Adler [2002] NSWSC 171; Gold Ribbon (Accountants) PL v Sheers [2006]

QCA 335 and ASIC v Rich [2009] NSWSC

1229.

[27] (1853)

3 De GM & G 19

[28] Michael Adams “The three pillars of good corporate governance” (2004) Risk Management 8 at <http://www.riskmanagementmagazine.com.au/articles/d3/0c03c8d3.asp> viewed 8 April 2011.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ALRS/2011/1.html