|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Computers and Law: Journal for the Australian and New Zealand Societies for Computers and the Law |

THE HACKER STRIKES BACK: EXAMINING THE LAWFULNESS OF “OFFENSIVE CYBER” UNDER

THE LAWS OF AUSTRALIA

BRENDAN WALKER-MUNRO,[*] RUBY IOANNOU[†] AND DAVID MOUNT[‡]

ABSTRACT

Over the past ten years, criminal offending utilising or involving computers and information systems has risen to become one of the most prevalent global security threats. With a low cost to entry and high potential benefits, cybercrime is a significant challenge for traditional forms of law enforcement investigation. In response, many Western democracies have passed laws permitting officers of policing and intelligence agencies to “hack back” – that is, to use computers to attack, infiltrate, damage or disrupt the information systems of criminal offenders. Yet the contours and boundaries of those laws are underexamined in the literature. How do these agencies pursue criminals operating extraterritorially? On what legal basis can police, intelligence services or even the military attack the computers of a criminal group? This paper seeks to chart the legal parameters of the use of cyber capabilities by Australian national security agencies on a domestic basis.

CONTENTS

In August 2020, The Australian newspaper published details of a discussion paper authored by the Department of Home Affairs.[1] According to the report, the Department was proposing legislative amendments to the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018 (Cth) (“the SOCI Act”) which would have permitted the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) – Australia’s top secret signals intelligence agency – to intervene in times of emergency. In those terms, the emergency was deemed any ‘immediate and serious cyber threat’ to Australia’s ‘economy, security or sovereignty, including threat to life’.[2] Once such an emergency situation arose, ASD would then be empowered to ‘take direct action to actively deny, disrupt and respond to malicious activity with corresponding powers and immunities’.[3] More recently, ASD was named in a ‘joint standing operation’ with the Australian Federal Police to target cybercriminals and foreign hackers.[4] Though the methodology of ASD remained highly classified, it was apparent from the report that Australia was contemplating the ability of ASD to “hack back”; that is, to use ASD’s own cyber capabilities against the would-be criminals.

But what does hacking back mean in legal terms? The exact circumstances in which hacking back might be contemplated, which types of emergency situations qualified, and exactly what those powers and immunities authorise is not well understood in the literature. Even more concerningly, since many digital connections are transnational, there exists significant capacity for hacking back to cross jurisdictional boundaries with greater ease. Australia possesses a unique geostrategic position, with an abundance of natural wealth, prosperous citizens, and high performing economies – all of which are rich targets for cybercrime. Notwithstanding, this topic is under-described in the current legal discourse.

The hack back phenomenon is not solely limited to Australia. In 2021, the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) published its report into the cyber capabilities of 15 countries. The IISS report claimed that the United States (US) ‘capability for offensive cyber operations is probably more developed than that of any other country, although its full potential remains largely undemonstrated’.[5] Following closely behind the US in cyber offensive capability were other members of the Five Eyes intelligence alliance – including the United Kingdom (UK), Australia and Canada – but also ally States such as Israel, France and Japan. States with traditionally counter-Anglo interests were also included such as China, Iran and Russia.[6]

The concerns here are far from academic. Not only do individual officers of the Executive need to be properly empowered for undertaking what are illegal acts if conducted by a member of the public, but Australia must maintain proper respect for the rules-based global order. The legislative underpinnings of hack-backs are also important from the perspective of paying respect to international sovereignty. In other words, how might it be legal for one country (such as Australia) to attack the software or hardware owned by a criminal group located in a second country, but passing through the digital connectivity infrastructure of a third country? Opportunities for major diplomatic or political incidents are manifest.

This paper will therefore seek to make some inroads into understanding and mapping the legality of “hacking back” under Australian law – in particular, its position as a tool of state intervention in the same vein as covert operations or spying. The focus of that analysis will be solely upon the domestic legislation of Australia that creates or permits opportunities for hacking back. Beyond the necessary discussion of aspects of international law that might create domestic obligations, this paper will not deal with any instrument or custom of international law.

Part 1 will introduce the idea of “hacking back” as a conceptual vehicle, exposing some of the issues which pose challenges for various legislation in Australia. Section 2 will examine the legal provisions which would enable deployment of cyber offensive capabilities inside Australia’s territorial boundaries. A brief history of the Acts permitting calling-out of cyber offensive assets will also be explored. Section 3 will then discuss the circumstances under which our national security agencies should be able to utilise their capabilities domestically. Concepts of emergency and necessity will be examined to formulate principles under which it could be considered permissible for Australia to hack back, as well as highlighting a significant deficit in the existing research literature around this topic. Finally, the paper will close with some summarising observations in Section 4.

In order to understand the legalities of hacking back in context, it is important to establish exactly what the paradigm refers to. Unsurprisingly, though States might have been quick to admit the existence of cyber units with these types of capabilities, they have been far more circumspect about exactly what those capabilities could allow or permit.[7] Early examinations of cyber capabilities generally grouped together by intention, distinguishing those that were considered “offensive” (being in an attacking or proactive capacity) from those that were “defensive” (being in a responsive or reactive capacity).[8] Pragmatically though, the definition between offensive and defensive has been obliterated. The joint US and Israeli cyber operation codenamed “Olympic Games” – which allegedly included the deployment of the Stuxnet worm against Iranian nuclear centrifuges – and the Russian WannaCry and NotPetya ransomware attacks were really both offensive and defensive in nature (at least according to their instigators).[9]

This difficulty is compounded by a lack of common language. Both US and UK military doctrine treat offensive capabilities in a similar way as defensive ones, by considering ‘cyber operations’ as the projection of power into the online, digital or virtual environments through the use of computer or information systems.[10] Canada legalised aspects of offensive cyber in 2018 under its counterterrorism laws but used the more euphemistic “active cyber” – the ‘prevent[ion of] threats before they reach Canadian (and possibly allied) targets’ – to describe their activities.[11] New Zealand remains staunchly in the defensive camp, despite possessing what some have called offensive capabilities.[12] Australia’s cyber security strategy does not define offensive or defensive actions,[13] nor did Australia’s international cyber engagement strategy.[14] However, both the-then Prime Minister of Australia[15] and Australian Signals Directorate[16] both made public statements in which they announced the existence of Australia’s offensive capabilities in this domain.

The predominant problem with both differentiating by intention or language appears to be trying to view cyber operations through the same lens as traditional kinetic warfare where, instead of two sides exchanging bullets or artillery, warfare in the cyber domain has tried to incorporate the idea of a back-and-forth exchange of viruses, worms and malware.[17] Much of the literature acknowledges that in the online world the traditional doctrines of warfare break down, non-State and State actors are indistinguishable and the lines between crime, terrorism and open war are impossible to define.[18]

“Hacking back” exemplifies these difficulties in both intention and language. The term generally covers those ‘proactive steps a victim of a cyberattack takes against their assailant in order to retaliate against their attacker’,[19] thus incorporating dimensions that are both defensive (retaliating against an attacker) and offensive (employing methods to manipulate, damage or destroy the attacker’s systems). By referring to the steps taken by “victims”, the literature also acknowledges that “hacking back” applies to non-State actors where ‘government departments and law enforcement agencies are unable or unwilling to effectively respond to cybercrime’.[20] Hacking back is also equally plagued by different terms, with ‘active defence’, ‘retaliatory hacking’ and ‘counter hacking’ being used interchangeably with “hacking back” in the literature.[21]

This paper will take a broad view of the term “hacking back”, with a view that it describes the actions taken by both State and non-State actors in response to a cybersecurity threat or incident to ‘manipulate, deny, disrupt, degrade, or destroy targeted computers, information systems or networks’[22] belonging to or supporting the actions of an attacker. There are several reasons for taking this approach. The first is that this definition incorporates those aspects of previous definitions on which scholars agree.[23] Secondly, this definition recognises the growing role of non-State actors in responding to cybersecurity threats[24] (and permits examining their call for greater legitimacy and legal protection, which will be dealt with later). Thirdly, it focuses the inquiry solely on responsive acts and thus excludes proactive or “first strike” capabilities.[25] Fourthly, this definition places the concept of “intercepting communications” (using interception warrants issued under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 (Cth) or its international equivalents) outside of the scope of the paper, as the defined act of hacking back involves solely retaliatory or reactive responses.

These definitions now having been established, we wish to examine how Australia currently legitimises the use of hacking back by its organs of national security, intelligence agencies, police, and the Australian Defence Force (ADF). These agencies are not only the most likely first responders to the types of national security threats in the cyber domain – such as adversarial States, cybercriminal groups, politically motivated extremists and “lone wolf” actors[26] – but also those traditionally funded and empowered to undertake such actions.

The national security apparatus of Australia is, at least by reference to its enabling legislation, notoriously fragmented: one recent legislative reviewer called the oversight of law enforcement and intelligence agencies ‘a dog’s breakfast’.[27] Intelligence agencies – being those constituting the National Intelligence Community (NIC)[28] – are predominantly covered by the provisions of the Intelligence Services Act 2001 (Cth) (“IS Act”). The only exception for this paper for NIC agencies is ASIO, which draws its powers from the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979 (Cth) (“the ASIO Act”). The AFP are also excepted from the IS Act, which are also given powers as constables under the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) (“Crimes Act”), but are still considered part of the NIC.

Australia’s military forces – the Army, Navy and Air Force operating under the unified banner of the ADF – can draw their operating legitimacy from two locations. The first is in statute, more specifically the powers accruing to Defence members participating in a “call out order” issued by the Governor-General under Part IIIAAA of the Defence Act 1903 (Cth) (“the Defence Act”). Part IIIAAA actions are reserved for responses to “domestic violence” where the ‘use, or potential use, of force (including intrusive or coercive acts) is required by Defence members’ in situations of threats to Commonwealth interests or at the behest of the States or Territories.[29] The other source of operational legitimacy for deployment of the ADF comes from the Crown prerogative which permits the Governor-General to direct the ADF to ‘be anywhere’ and thereby undertake such operational activities as he or she sees fit.[30]

Finally, the policing forces at the State and Territory level are usually dependent entirely upon the enabling legislation in each of their jurisdictions. However, amendments to the Surveillance Devices Act 2004 (Cth) (SDA) in 2021[31] introduced a series of warrants capable of supporting hacking back for State and Territory police. Generally speaking, such warrants permit police officers to hack into a computer – whether located in Australia or elsewhere – and modify, alter, delete or destroy information on any such computer or network.[32] Whether or not those provisions enable the populist concept of “hacking back” to occur is a rather more nuanced question.

The NIC operates on what can largely be considered a geographical divide – agencies such as the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS), Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), Australian Geospatial-Intelligence Organisation (AGO) and the Defence Intelligence Organisation (DIO) have a foreign remit, to collect and process intelligence and to conduct operations involving threats not located within Australia. Given these agencies are largely bound by the limitations in the IS Act,[33] their utilization is predominantly connected to preventing or disrupting foreign cybercrime[34] or assisting the ADF with military operations overseas.[35] Two recent examples include the targeting of Islamic State assets during “Glowing Symphony”[36] and assisting Australian Federal Police investigate the hackers behind the theft of health insurance information from Medibank Private.[37]

Conversely, the Office of National Intelligence (ONI) is constituted under a separate Commonwealth Act[38] and has only leadership and coordination roles within the NIC ecosystem. ONI is limited by statute to the leadership and ‘evaluation of matters’ involving the NIC, but not the NIC agencies themselves, and to advise the Prime Minister on the results of such evaluations. These evaluations are curtailed to the extent that they may or do ‘inappropriately impact on, or encroach on the functions, powers and responsibilities’ of members of the NIC.[39]

A strong prospect for the authorisation of NIC agencies to conduct “hacking back” under a legitimate framework is contained in the ASIO Act.[40] Effectively, the ASIO Act empowers the Director-General of ASIO to seek a warrant from the Attorney-General if:

...he or she is satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for believing that access by the Organisation to data held in a computer (the target computer) will substantially assist the collection of intelligence in accordance with this Act in respect of a matter (the security matter) that is important in relation to security.[41]

The necessary test for the Attorney-General to issue such a warrant is three-fold. Firstly, the warrant must specify a target computer by reference to some defining characteristic that separates the target computer from unrelated, nearby or connected devices.[42] Secondly, there must exist a security matter upon which the Organisation has collected, or is proposing to collect, intelligence. Thirdly, the Director-General must hold a reasonable belief based on reasonable grounds that the Organisation gaining access to the target computer will be ‘substantially assist’ the collection of intelligence in respect of that security matter.

These tests place important boundaries around the exercise of ASIO’s hacking back power. The concept that a warrant cannot authorise a “fishing expedition” – usually described as an exercise of statutory power in the absence of reasonable grounds, conducted in the hope of finding some evidence which justifies the intrusion – has been long established in the common law.[43] In this case, a computer access warrant must be directed towards a target computer, defined with some precision in order to comfort the Attorney-General that the Organisation’s access to that computer is both possible and reasonable to achieve the objectives of the warrant.

Further, the use of a computer access warrant under the ASIO Act requires a connection to a security matter both generally but also in relation to the collection of intelligence from the target computer. This must be a matter related to security as it is defined in the Act,[44] requiring that ASIO by necessity limits the circumstances in which a warrant of this type might be sought or granted (although ASIO does have a derivative use provision enabling them to copy any data relating to a security matter which was not mentioned in the warrant[45]).

Finally, any “hacking back” conducted under a computer access warrant may only alter, damage or destroy data on that computer for the purpose of obtaining access to the data the subject of the warrant and/or concealing the activities of ASIO.[46] A computer access warrant does not authorise ASIO or its officers or agents to alter, damage or destroy data for any other purpose (i.e., disrupting or preventing crime), though the Act curiously only protects lawful use of a computer or telecommunications network by persons involved with the target computer and remains silent about unlawful use.[47]

For completeness, there are two other forms of warrant which might also be relied upon by ASIO to conduct “hacking back” activities. An ‘identified person warrant’ may be issued by the Attorney-General on the application of the Director-General of ASIO, and where the Attorney-General is satisfied of two conditions: firstly, that a named person is involved in activities prejudicial to security; and secondly that the issuing of the warrant will, or is likely to, ‘substantially assist the collection of intelligence relevant to security’.[48] Once issued, the warrant may be directed to that named person’s electronic devices if, and only if, ASIO can satisfy the Director-General or Attorney-General at a later time that the data sought ‘will substantially assist the collection of intelligence relevant to the prejudicial activities of the identified person’.[49] ASIO may then ‘if necessary to achieve that purpose, add, copy, delete or alter other data in the target computer’,[50] but are bound by the same prohibitions on loss or damage as computer access warrants.[51]

The second form of warrant under which a computer might be hacked back is under a foreign intelligence warrant.[52] Rather than a separate class of warrants, foreign intelligence warrants are those issued under the same provisions above (sections 25A and 27C) but are directed not to “security” matters but “foreign intelligence” matters which arise within Australia.[53] These warrants, again requested by the Director-General and granted by the Attorney-General, carry an additional threshold test. Prior to issuing a foreign intelligence warrant, the Attorney-General must receive advice from the Defence Minister or Foreign Affairs Minister to the effect ‘that the collection of foreign intelligence relating to that matter is in the interests of Australia's national security, Australia's foreign relations or Australia's national economic well-being’.[54] Foreign intelligence warrants also do not authorise the damaging of computers which would interfere with lawful use.[55]

Having thus exhausted all the hacking provisions under the ASIO Act, it remains to consider whether any of the other NIC agencies might be able to conduct cyber offensive activities within the domestic territory of Australia. IS Act agencies – including ASIS, AGO and ASD – function under the framework of Ministerial authorisation and directions.[56] A direction imposes obligations on an NIC agency to refrain from conducting certain activities in respect of Australian persons, whether those activities are the production of intelligence,[57] assistance to military operations by the ADF[58] or the prevention or disruption of cybercrime[59] unless the Minister authorises those activities.

To provide such an authorisation, the Minister must be satisfied of numerous matters;[60] however, this is not the greatest difficulty which faces IS Act agencies in attempting to “hack back” within Australia’s boundaries. The limitation placed upon these agencies by the IS Act clearly excludes much of their capabilities from operating inside Australia on their own initiative. For example, ASIS may only collect intelligence about ‘the capabilities, intentions or activities of people or organisations outside Australia’, or ‘undertake such other activities as the responsible Minister directs relating to the capabilities, intentions or activities of people or organisations outside Australia’[61] (emphasis added in all cases).

AGO and ASD have similar limitations placed upon them. AGO for example is limited to producing various forms of geospatial intelligence on persons and organisations ‘outside Australia’,[62] whilst ASD is limited to preventing or disrupting cybercrime ‘undertaken by people or organisations outside Australia’.[63] Neither agency’s core remit relates to activities undertaken within the territorial boundaries of Australia and in fact excludes those activities by operation of statute. There are however, several interesting loopholes which might permit IS Act agencies participating in the use of “hacking back” without offending the limitations imposed on them.

The first is where these agencies have functions bestowed upon them by the IS Act which do not carry the “outside Australia” caveat. In the case of ASIS this is counter-intelligence activities[64] (i.e., ‘the identification and neutralization of the threat posed by foreign intelligence services, and the manipulation of those services for the manipulator’s benefit’[65]), and for ASD this is their technological protection function (i.e., to ‘protect specialised technologies acquired in connection with the performance’ of any of ASD’s other functions under the IS Act[66]).

Broadly speaking, both ASIS and ASD might be permitted to conduct hacking into an offender’s computer where that offender was geographically located inside Australia if, and only if:

• In the case of ASIS, they reasonably believed that the offender was working for, or acting on behalf of, a ‘foreign principal’[67] and such hacking back activities were reasonably necessary to fulfil ASIS’ counterintelligence functions; or

• In the case of ASD, the offender was attempting to steal, subvert, damage or destroy some particular specialised technology which ASD had acquired in the performance of its other IS Act functions, i.e., specialised cryptographic, communication or computer technologies.[68]

The vagueness of these terms should give IS agencies cause for caution; however, there are more pressing issues. In both cases, the conduct of either or both of ASIS or ASD in hacking back a domestic Australian offender would require both a Ministerial direction and authorisation, and a Ministerial direction cannot be issued in respect of activities which would require a warrant under the ASIO Act (such as a computer access warrant).[69] Even in the event that a direction could be issued, the Minister would need to be satisfied, as a precondition to the giving of an authorisation that ‘there are satisfactory arrangements in place to ensure that the nature and consequences of acts done in reliance on the authorisation will be reasonable, having regard to the purposes for which they are carried out’.[70] The reasonableness of the acts done will be difficult to justify in circumstances whereby the same activities justifying ASIS or ASD’s involvement would also more reasonably justify ASIO’s jurisdiction as a matter affecting Australia’s security.[71]

The second pathway under which hacking back might be contemplated is under the assistance functions accruing to IS Act agencies,[72] not only as discrete functions of their agencies but also under sections 13 and 13A of the IS Act. These activities do not automatically mandate Ministerial directions or authorisations, though they may be covered by other directions or authorisations depending on the activities being contemplated. Whether providing assistance to the AFP, a State or Territory Police Force, a specialist regulator or other Department, there is the possibility that the Minister could issue an authorisation for activities involving the deployment of such capabilities inside Australia for the purpose of its assistance functions.

The necessary test for the Minister is – hinging on use of the word “may” in section 9(2) of the IS Act – dependent solely on whether he or she was reasonably satisfied that an authorisation would permit activities necessary for the proper performance of one of the relevant IS agency’s functions, there are satisfactory control arrangements in place to not exceed the authorisation, and those arrangements can ensure that the ‘nature and consequences of acts done in reliance on the authorisation will be reasonable’.[73]

This construction too should be treated with some scepticism. The cooperation provisions in the IS Act explicitly limit the boundaries of cooperation with a government agency to the performance of the cooperating agency’s functions. For example, the AFP has policing and investigative functions to deal with cybercrime.[74] ASD has a function to ‘provide material, advice and other assistance... on matters relating to the security and integrity of information that is processed, stored or communicated by electronic or similar means’,[75] and the IS Act permits ASD to assist the AFP with the performance of the investigation function.[76] Yet the exact practical assistance which ASD can provide is circumscribed by application only to persons and organisations located outside Australia.[77] Though this limitation is specifically carved out when IS Act agencies cooperate either with ASIO or each other, the nature of such support is specifically limited to what is asked by the requesting agency, i.e., IS Act agencies cannot venture outside the parameters of their lawful functions where this has not been specifically requested.[78] ASIO activities would need to be authorised by a warrant under the ASIO Act, and IS Act agencies – even those cooperating with one another – would be limited by the application to persons and organisations outside Australia.

In summary, the above analysis shows that the deployment of Australian “hack backs” by the IS Act agencies (ASIS, AGO and ASD) would not be lawful if it was deployed inside Australia, both by reference to the powers and functions of those agencies. Instead, ASIO appears to retain the primary jurisdiction for the conduct of hack backs in Australia under the authority of computer access warrants; however, this capability is limited to only the collection of intelligence about the activities of the offender and would not extend to disrupting or destroying the offender’s data or systems in response to an incident. The question of whether ASIO or the IS Act agencies could assist either of the ADF or Police forces to do so will be answered in the subsequent sections.

The ADF first established an Information Warfare Division in 2017 as part of its Joint Capabilities Group, with a specific remit to conduct cyber operations alongside traditional forms of military operations and armed conflict.[79] A year after its establishment, in 2018 the Australian Strategic Policy Institute then examined the publicly available information regarding how ADF capability worked alongside ASD, concluding that ‘[a]ny offensive cyber operation in support of the ADF is planned and executed under the direction of the Chief of Joint Operations and, as with any other military capability, is governed by ADF rules of engagement’.[80] Since that time, ADF personnel and materiel have focused on the domain of cyber in extensive training and capability development works.[81] In other words, deployment of offensive cyber capabilities – “hacking back” – by the ADF would be conducted under the imprimatur and legality of a military operation and not an intelligence operation.

So, what are the legal parameters of a military deployment in which hack backs might be used? And could Australia ostensibly be a location in which such a deployment could occur?

The answer is not straightforward. Firstly, Australia has a very complex system relating to domestic deployment of its military force under call out orders contained in Part IIIAAA of the Defence Act. These deployments are either to protect Commonwealth interests from real, perceived, or anticipated threats[82] or in response to a request from a State or Territory.[83] In both cases, there is also likely to be a need for the Governor-General to be satisfied that a state of ‘domestic violence’ exists – a term that lacks definition anywhere on Australia’s statute books[84] – but would likely require substantial threat of or actual loss of life or Commonwealth assets.[85]

Secondly, the ADF is commanded by the Governor-General[86] through the Chief of the Defence Force.[87] As the King’s representative in Australia, the Governor-General may also choose to deploy the ADF under the prerogative of the Crown or under doctrine of necessity;[88] neither of which would require authorisation by an Act of Parliament nor a decision by a Minister.[89] The ADF could also undertake certain “pre-deployment” actions and functions under its own initiative and without vitiating the exercise of either executive power[90] or the Crown prerogative.[91]

Lastly, whilst the High Court of Australia might have been willing to impose boundaries on the executive prerogative in CPCF,[92] these boundaries are not as persuasive to military deployments. This is generally because the call out order regime contains a caveat provision in section 51ZD of the Defence Act, essentially severing any need for the ADF to rely upon call out orders in every situation in which they proposed to deploy their capabilities: ‘[t]his Part does not affect any utilisation of the Defence Force that would be permitted or required, or any powers that the Defence Force would have, if this Part were disregarded’.[93]

Whether the activating condition is the making of a call out order or the ADF’s inherent capability to deploy in response to an emergency situation will in turn determine the legality of ADF use of “hacking back” capabilities. For example, assuming that a call out order has been made by the Governor-General – and it matters not whether the situation involves a State request or the protection of Commonwealth interests – the deployment of ADF cyber capabilities is a command decision for the Chief of the Defence Force. If the hacking back is proposed in the context of a broader Police investigation or response, the use of ADF assets to do so would not only need to be ‘reasonable and necessary’ to achieve a purpose consistent with the originating call out order,[94] but also at the request of the Police Force of the hosting State or Territory.[95]

Assuming it remained within the scope of the call out order, the ADF’s use of hacking back capabilities could either be explicitly authorised by the Minister in an authorisation under the Defence Act[96], or apply by virtue of the Minister’s declaration of a specified area[97] or in defence of critical infrastructure.[98] Hacking back could then be used by the ADF under a call out order if they needed to support more traditional security operations such as achieving the capture or recapture of an asset, in response to a hostage situation or to put an end to the state of domestic violence.[99]

On the other hand, the use of ADF assets to perform more traditional policing roles such as search and seizure[100] for evidentiary purposes is ultimately unsupportable in law, as the search powers available under a call out order must be observed at all times.[101] Nor do search powers under call out orders generally permit ‘remote’ or ‘online’ search and seizure, whether conducted under a search determination[102] or the power to search vehicles or aircraft.[103] The exercise of hacking back powers to search an offender’s computer by military forces also butts up uncomfortably against the common law privilege against self-incrimination.[104]

Alternately, if the ADF deploys its cyber assets domestically under Crown or executive prerogative, it could operate without the constraints and requirements of Ministerial authorisations and simply rely on the balance of Crown power to support it ‘responding to emergencies or keeping the peace’.[105] There are two significant problems with such a suggestion, especially in the contentious field of cyberattacks and military forces more generally.

The first issue is that the deployment of military forces without a statutory footing offends the ‘very old common law proposition that the Royal prerogative does not extend to entering private property for the purposes of keeping the peace’.[106] Though the ADF has an absolute ability to protect and maintain the laws of the Commonwealth, this ability flounders in the absence of a clear and present danger to the Commonwealth itself – and, if such a danger existed, would justify the making of a call out order in the first place.

The second issue arising from the use of prerogative to deploy military forces is that the ADF loses the power and protection of the Defence Act in doing so. Not only are its officers and personnel open to criminal or civil liability in the pursuit of their duties,[107] but they lose all manner of statutory powers that could arise under the issue of a call out order or Ministerial authorisation. Deployments of ADF personnel during the management of the COVID-19 epidemic in Australia are instructive in this regard: they derived their powers from the various biosecurity and emergency management declarations, not from the provisions of the Defence Act.[108]

Finally (and for completeness) it is worth examining the assistance provisions of the IS Act previously covered as they might apply to domestic military operations. The position of ASD is complicated – they are not strictly part of the ADF even if they may employ or second ‘any officer, sailor, soldier or airman’[109] and thus cannot be given orders by the Governor-General.[110] However, ADF may request ASD assistance either pursuant to the exercise of Defence powers[111] or as a request under the IS Act.[112] Both have their difficulties. It is possible to conceive a scenario where the Police make a request of the ADF who then make a request of ASD who might then collaborate with ASIO... hardly an efficient use of time or resources. It might also be seen by the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security – the oversight body of IS Act agencies – as a way of sidestepping legitimate regulatory controls built into the law.[113]

Having concluded this analysis of the ADF’s hacking back capabilities, it seems unlikely that deployment of military cyber capability inside Australia’s territory would be prima facie lawful under the Defence Act 1903. Even accounting for the support provisions enabling IS Act agencies, without the very clear authority granted to the ADF by the Governor-General in the form of a call-out order, the use of hacking back capabilities by military personnel inside Australian territory seems to be extremely vexed.

This of course neglects collective effects of the residual powers of statehood available to Australia,[114] the Governor-General’s command privileges[115] and the common law doctrine of necessity viz where a State can act in its own self-defence. Under that collection of legal powers and immunities, the ADF can respond to a foreign threat to Australia’s national security as:

[t]he conduct of war appears to be a prerogative power of the Crown and military forces exist primarily to execute this prerogative on the sovereign’s behalf... the exercise of martial law in the factual circumstances of a war or insurrection is an aspect of prerogative power and not the common-law doctrine of necessity available to any person. This is a preferable view because it is not for any person to exercise the military power of the Crown or to claim to do so on its behalf.[116]

In those circumstances where the ADF is required to deploy domestically to confront a foreign threat, it would be permitted to utilise the full range of its warfighting capabilities (including “hacking back” and similar information warfare style methodologies).

We therefore turn finally to the legal status of policing hack backs.

The final pathway for examining Australian legislative support for hacking back falls now to the status of policing forces under the Surveillance Devices Act 2004 (Cth) (“SDA”), but also those bodies charged with various forms of integrity investigation such as the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity, Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC), and the independent standing anti-corruption commissions of the States and Territories.[117] Each of the State and Territory police forces are also recognised as ‘law enforcement agencies’ and their members (including secondees) as ‘law enforcement officers’.[118]

The SDA creates and maintains a warrant scheme for both Commonwealth law enforcement as well as State and Territory law enforcement agencies investigating State offences with a Federal aspect.[119] This is highly relevant to discussions around cybercrime and online malfeasance, as one of the core provisions of these types of offences are those which have ‘involved an electronic communication’.[120] Divisions 4 (computer access warrants), 5 (data disruption warrants) and 6 (network activity warrants) of the SDA create the framework of most relevance to the discussion in this paper.

Computer access warrants under the SDA bear some similarity to their ASIO Act counterparts; however, the applicant is a ‘law enforcement officer’[121] (not the Director-General of ASIO) and the issuing authority is an ‘eligible Judge’[122] or ‘nominated AAT [Administrative Appeals Tribunal] member’[123] (not the Attorney-General). The same test for reasonable grounds applies to the consideration of the application, but the criteria upon which those reasonable grounds are based changes significantly under the SDA (however, only the ‘relevant offence’ grounds are in scope here[124]).

The issuing authority must also consider numerous criteria in deciding whether to make a computer access warrant including the nature and gravity of the alleged offence,[125] the privacy of any person the warrant may affect,[126] whether alternative methods might obtain the same evidence or information,[127] and the likely value of evidence or intelligence obtained.[128] Like an ASIO warrant, if the issuing authority is satisfied then the warrant must sufficiently particularise both the alleged offences and the target computer which is the subject of the warrant.[129]

But there are difficulties with the use of computer access warrants as a vehicle to hacking back offending targets; again, like their ASIO equivalents the warrant only authorises access to the computer, not damage or disruption. Law enforcement officers are permitted to access and obtain the data subject to the warrant only – this does not authorise deletion, modification, destruction or damage to any data or system.[130] Concealing the access also does not authorise the use of disruptive, destructive, or damaging methodologies beyond the bare minimum necessary to achieve the purposes of the warrant.[131]

Nor do network activity warrants permit any broader forms of “hacking back” in the terms described in this paper.[132] Like computer access warrants, the purpose of network activity warrants is to map out and obtain evidentiary information relevant to a ‘criminal network of individuals’.[133] This in turn is defined as a ‘electronically linked group of individuals’ who use, communicate or facilitate the commission of a relevant offence using online or digital methods.[134] These warrants are also more restricted in their application, in that only the chief officer of the AFP or ACIC may apply for a network activity warrant,[135] and that data on the target computer relates to the network of individuals and is ‘relevant to the prevention, detection or frustration of one or more kinds of relevant offences’.[136] Destruction or damage to data or systems is generally not permitted.[137]

The final form of warrant – data disruption warrants – are also limited to law enforcement officers of the AFP or Australian Crime Commission.[138] In order to bring an application, relevant offences must have been or are about to be committed, and the disruption of data in a target computer must achieve either the frustration of the commission of the relevant offence relating to that data (data-based warrant[139]), or the frustration of offences of a similar kind (offence-based warrant[140]). Data disruption warrants also requiring an endorsement from a more senior officer within the agency who has ‘relevant skills, knowledge, and experience to endorse the making of applications for the issue of data disruption warrants’.[141] Again, the list of matters to be considered by an eligible Judge or nominated AAT member is daunting and comprehensive.[142]

Quite unlike computer access warrants and network activity warrants, data disruption warrants clearly fall within the parameters of “hacking back” as this paper describes it. Data disruption warrants may be applied for unsworn, permitting law enforcement to respond quickly to incidents as and when they occur (noting the requirement to provide a sworn application within 72 hours of the making of the application[143]). The warrants precisely authorise and permit the damage, deletion and destruction of data which is subject to the warrant as well as authorising the alteration, copying or deletion of any other data on the target computer whilst the warrant is in force – so long as the disruption of offending named in the warrant is achieved.[144] Although the usual caveat of restricting damage that would impinge on lawful uses of the target computer applies,[145] contextually the bar is much lower given that the purpose of the warrant is disruption and not evidence gathering.

It is also apposite to note that the provision of assistance to law enforcement – either by IS Act agencies or by ASIO – is much cleaner and easier under the imprimatur of a data disruption warrant. Both ASD capabilities (leveraging the technical expertise and advice function[146]) and ASIO (who have a specific law enforcement assistance function[147]) could be brought to bear under the supervision and direction of law enforcement capabilities. Equally, were ADF assets to deploy following a call out order or exercise of executive prerogative, their subordination to law enforcement and incorporation under the warrant regime would clothe them in an appropriate degree of legal protection. The construction of the SDA also seems to prefer this approach, as it requires a data disruption warrant to ‘authorise the doing of specified things ... in relation to the relevant target computer’[148] (emphasis added). The Act thus remains entirely agnostic about who does those specified things, whether it is a law enforcement officer, ASD or ASIO agent, or military officer or enlisted.

The strongest support under Australian law for the use of “hacking back” capabilities appears to be under the SDA as a primarily law enforcement focused exercise. The use of such capabilities under either the intelligence agencies or military forces of Australia, acting alone or in concert, are riddled with statutory imperfections and linguistic difficulties.

Far from being an academic concern, this lack of precision not only compromises the legitimacy of such operations but potentially renders both intelligence and military personnel liable to criminal charge or civil suit. The use of such a controversial capability cannot be supported by reference to imprecise legal frameworks and ambiguous prerogatives.

By focusing on law enforcement as the primary counter-cybercrime agency in Australia, we achieve a degree of ‘coherence and consistency between the essential elements of the regime and correlative authorisations elsewhere in legislation’.[149] But could Australia do it better? The next section will examine whether Australia should alter its laws to better reflect circumstances under which it may use its “hacking back” capabilities in the future.

Having examined some of the various legal frameworks under which “hacking back” would be legitimised, there remains a policy question at what point recourse to those frameworks should be had. Obviously not all cyber incidents and not all cyber-crimes would qualify for an immediate and overwhelming response by national security agencies and might breach Australia’s obligations under international law.[150] On the other hand, failing to respond adequately to a cybersecurity incident may result in further damage and cost which could have been avoided. What is therefore required is a policy that has ‘the aim of normalizing uncertainty...[and] the aspiration that the uncertainty, the exceptional, be tamed’.[151]

There are international examples of how such a policy could be formulated. Kesan and Majuca describe that hack backs should only be allowed where three conditions can be met: one, that obtaining a court order or similar restraint is unlikely to be successful; two, there is a serious prospect that the hack back will not impact innocent third parties; and three, the damage to the victimised system cannot be adequately mitigated.[152] The trigger for engaging in such activities appears to largely follow a cost-benefit analysis dependent on the likelihood of success by the defender versus the likelihood of collateral damage, mistakes in attribution, lack of legitimacy and the possibility of normalising destructive hacking.[153]

Another benchmark available in international law is the doctrine of countermeasures, being the engagement in ‘measures that would otherwise be contrary to the international obligations of an injured State vis-à-vis the responsible State, if they were not taken by the former in response to an internationally wrongful act by the latter in order to procure cessation and reparation’.[154] Under this doctrine, “hacking back” would only be permitted under two conditions: firstly, the State engaging in a prior wrongful act must be identifiable and attributable for that act; and secondly, the hack response must produce a temporary result that is ‘instrumentally directed to induce the responsible state to cease its violation’.[155] The obvious limitations upon such a trigger are the cessation of the originating cyberattack, as well as any response that would threaten human rights or amount to an unacceptable use of force.[156]

A third form of policy construction was envisaged by Lahmann, where he examined the lawfulness of Germany’s 2005 Aviation Security Act – which permitted the executive to shoot down planes hijacked by terrorists in a 9/11 scenario – and the potential for the Act to ‘directly affect innocent individuals and their human dignity’.[157] In Lahmann’s view, such regimes needed to abide by four conditions:[158]

• An operative cyber emergency regime needs to comprise precise and workable definitions of key concepts;

• The regime should only require consideration of stakeholder interests if they will foreseeably and directly be negatively affected by the “hacking back” operation;

• The regime should eschew ex ante attribution (which may not be technically possible at the time) in favour of ex post assessment of the legitimacy of the “hacking back” action; and

• As a State with a cyber offensive capability, it has a duty to put some legal process in place that follows principles of the rule of law and ensures consistency.

A fourth, more consequentialist approach by Carr and Schmitt described six criteria: severity, immediacy, directness, invasiveness, measurability, and presumptive legitimacy.[159] However, it is worth observing that any “hack back” which meets all six criteria is suggested to amount to an armed attack which would warrant a military response. As we are focusing the use of State capabilities against non-State actors within a domestic threat scenario, and in many (but not all) circumstances these use of an “armed attack” cannot be justified.

All of these benchmarks stipulate that “hacking back” must not be conducted in an unfettered manner and requires some form of soft limitations, even if the law permits that conduct to be engaged in. For example, Germany’s 2005 Aviation Security Act may legally allow the shooting down of a hijacked plane – a concept also authorised under Australian law[160] – the question remains whether the Executive could legitimately do so in every circumstance. Another obvious limitation for each of these proposed policy frameworks listed above is that they take the approach of “hacking back” as an activity by one State against another, as opposed to our present analysis which involves the activity of a State (Australia) against non-State actors located within its own territory.

In fact, the literature is all but silent on the legitimacy of hacking back as a tool of State power. Arguments broadly seem to centre on three themes: is a hack back effective, proportionate, and preferable compared to other less intrusive and less damaging options.[161] The methodologies of hack back are also highly relevant: actions which install “beacons” – forms of spyware which identify or flag the attacker’s computer or keystrokes – are generally considered a more appropriate and rational response than erasing or modifying data in the target system, or ultimately the State’s use of ransomware or cyberweapons.[162]

Given the lack of academic consideration in this area, we will propose four matters that national security agencies in Australia (or other States) should have regard to prior to or during the conduct of hacking back activities. These matters draw the important link between what is legally authorised under Australian law from the preceding sections and what is legitimately warranted. In so doing, we synthesise Lahmann’s analysis of the international doctrines of emergency and necessity with

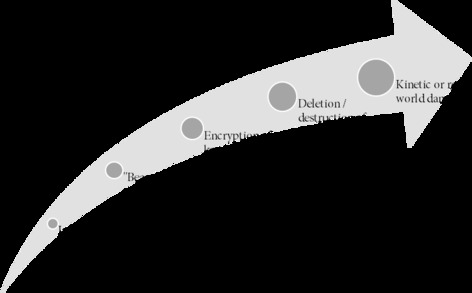

Under both an ASIO Act and SDA warrant, different levels of interference in a target computer might be warranted. Whilst the warrant must describe what methodologies the warrant authorises can be performed,[163] exactly whether the effect those methodologies result in is appropriate will vary dependent on the circumstances. We have provided a non-exhaustive spectrum of these effects in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Spectrum of possible effects of “hacking back”

Consider the following by reference to Figure 1. It may be sufficient for investigators to simply gain access to the data on a target computer under an ASIO Act or SDA warrant, and from there directly monitor what activity occurs (including communications between the various parties of interest). This has the benefit of being conducted covertly and may not necessarily involve any physical changes to the data in the target computer. A warrant authorising this type of effect might be more reasonable in circumstances involving preparatory or anticipatory offences where the “hacking back” might be supplemented traditional law enforcement techniques or procedures.

An escalation could involve the installation of “beacons” as described earlier (which flag or identify the physical location of the target computer or persons of interest) or spyware (which might allow for remote monitoring, logging of keystrokes, etc.). Beyond those measures, the spectrum in Figure 1 displays increasingly more obvious forms of harm and damage, such as encrypting the target’s data (and thus rendering it unusable[164]), deleting or destroying it, or manipulating a system or some of its connected components to generate a kinetic or real-world damage.[165] Deploying a “hack back” which causes real-world harms would need to be reserved for the most serious of incidents and really as a last resort for fear of normalizing cyber-attacks.[166]

A technical method of determining the scale, scope and sophistication of the target offender is to examine which “layer” is being attacked. Under the Open System Interconnection (OSI) model, each system contains seven layers (moving from highest to lowest levels of abstraction):

• Application layer

• Presentation layer

• Session layer

• Transport layer

• Network layer

• Data link layer

• Physical layer

Attacks which target the lower layers are generally more favoured in attacks against infrastructure involving national security,[167] whereas those attacking the higher layers are traditionally associated with wider network or social engineering incidents.[168]

Agencies should then have regard to the nature of the offenders that can be identified and assessed. Is the suspected person a foreign State actor, or an agent acting on behalf of a foreign principal? Or are they merely a motivated opportunist or “lone wolf”? What resources are they suspected or known to have, either in respect of ‘relevant offences’[169] or ‘security matter’[170] (which could ground an application for a warrant)? If they have or are already launching a cyberattack of some kind, how much time and space do they have to perform follow-up or secondary attacks? Have they made specific threats against known vulnerabilities or targets, or are the threats vague and lacking in substance?

Each of these questions shapes the form of the cyber response that is warranted under either of the ASIO Act or SDA. Obviously a well-resourced, highly motivated actor working on behalf of a foreign State will require a stronger and more decisive “hacking back” response than that used against an individual. In the same manner, offenders with a deep resource pool and the capabilities to conduct follow-up offences should be considered for more serious interventions to disable future incidents and discourage repetition. The nature of the target also helps shape the degree to which different national security agencies might need to coordinate their responses to “hacking back” – the more sophisticated, the more coordination is needed.

The third matter that national security agencies should have regard to involves the severity of actual or anticipated harms to the affected systems. In the early days of a cybersecurity incident or attack, this may be difficult to achieve; alternately, in the case of recent ransomware attacks against critical infrastructure like a hospital or gas pipeline the actual harms can be more obvious.[171]

A mere risk-benefit analysis is insufficient.[172] A “hack back” by national security agencies to protect a piece of critical infrastructure[173] (even in anticipatory or ex ante circumstances) might well invoke a higher order response, even if the scope of the proposed harms to that infrastructure was of a lesser nature. Situations where harms have already occurred – such as the conduct of a terrorist attack, or the use of a weapon of mass destruction for example – which might automatically warrant higher-order national security responses than anticipatory or preparatory actions, or where investigations into conduct are still covert.

A better rule of thumb might be to look to the emergency doctrine in international law referred to by Lahmann and consider whether the actual or anticipated harms involve “grave and imminent peril” to an “essential interest” of Australia.[174] This is especially the case where warrants may be obtained pre-emptively.[175] In cases where national security agencies are contemplating a higher order “hacking back” response, they ought to give consideration to whether their target poses a grave and imminent threat to an essential interest of Australia, and be capable of articulating exactly what those forms of threat and interests are.

Articulating how threats meet those definitions would also be useful for issuing authorities, to assist them in determining whether the issue of warrants is reasonable, necessary and proportionate. Independent arbiters in each warrant regime, being the Commonwealth Ombudsman for the SDA[176] and the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security in respect of ASIO,[177] would also be better placed to assess the legitimacy of each warrant granted if the application for them was couched with reference to those terms.

Finally, agencies should have regard to the likelihood of possible harms to innocent third parties, whether they are other users of a system or network, or in the case of mistaken attribution, i.e., an actor used an interposing computer system to disguise their digital footprint, resulting in agencies “hacking back” into the wrong system. Lahmann counselled that “hacking back” regimes should only consider and protect those private actors whose interests would ‘foreseeably and directly be negatively affected’.[178] One of the ways in which he envisaged the regime could take account of these interests would be the issue of warnings to owners or custodians of affected systems of an imminent “hack back”, permitting those owners or custodians time to implement less intrusive or damaging interventions that might address the original incident.

For obvious reasons, the notion of law enforcement (AFP) or intelligence agencies (ASIO) issuing warnings ahead of a hack back activity – where those agencies could be responding to serious criminal offences or threats to national security – is hardly a practical one. However, both the ASIO Act and SDA do import requirements involving the consideration of stakeholders who might be affected. Both ASIO Act and SDA warrants incorporate provisions which require the applicant to give, and the issuing authority to consider, reasonably foreseeable impacts on innocent third parties.[179] Both warrants also do not extend to authorising the damage of systems which are not contained within the scope of the warrants, and which might be foreseeably affected by the activity.[180]

If something were to go wrong, there are mechanisms in Australian law to hold national security agencies accountable if they have erroneously targeted an entirely uninvolved system or acted disproportionately.[181] The SDA has a specific head of statutory power under which an aggrieved person may obtain compensation from the Commonwealth.[182] In any event, the oft-cited case of A v Hayden[183] – which involved allegations against ASIS operatives who, during a training exercise brandished firearms in a hotel, took a manager hostage, and caused criminal damage to the premises – clearly shows that illegal acts undertaken by organs of Australia’s national security apparatus will not be excused unless explicitly authorised by statute or order of the court. A v Hayden supports the proposition that any act undertaken by an agency of the State involving “hacking back” that is not authorised by law will attach civil liability to the Crown.

By examining Australia’s statutory frameworks for deployment of “hacking back” capabilities amongst its intelligence, military and law enforcement arms, there are several observations that we can make in conclusion.

Firstly, Australian law largely prohibits the granting of Ministerial authorisations and directions for “onshore” or domestic targets,[184] and the recent Richardson Review of the legislation of NIC agencies recommended against any such laws being changed.[185] In all other cases, the ASIO Act and SDA require the issue of a warrant (either by the Attorney-General or by a Judge or authorised AAT member respectively) on their satisfaction of certain matters. However, the same agencies would largely be authorised to conduct hack backs in the case of protecting critical infrastructure from cyber offensive activities – especially in response to emergency or emergent situations.

In the context of the ASIO Act, the modification or deletion of data must be relevant to the security matter for which the warrant is being sought, subject to the limitations imposed regarding interfering with lawful use of computers or causing loss or damage to other persons.[186] For the SDA, an officer of the AFP or ACIC must set out their reasonable suspicion that ‘disruption of data held in the target computer is likely to substantially assist in frustrating the commission’ of offences either involving the data in the target computer, or relevant to the application.[187] The relative satisfaction of those issuing authorities is not reached lightly, and promotes a degree of consistency across the situations in which “hacking back” will be conducted by our national security agencies.

Secondly, these statutes place ambiguous and imprecise boundaries on the lawful mechanism for counter-cybercrime capability to be used in a domestic threat scenario. The closest legitimate analogue is the issue of data disruption warrants under the SDA to law enforcement officers; however, the exact pathway to satisfying the issuing authority, the nature of what is authorised under a data disruption warrant, and the overlap of such warrants with cooperation provisions in the ASIO Act and IS Act in respect of domestic targets remain unnecessarily ambiguous. The cybercrime being targeted would also need to be relatively large in scale and/or organised. It is highly unlikely that Australia would deploy significant cyber offensive capabilities against foreign (or domestic) scammers or individual instances of cybercrime.

Thirdly, though Australia’s legislation is broadly compliant with normative customs regarding “hacking back”, the policy parameters of such activities require significant academic and governmental examination. By subjecting the capability to a specific warrant regime, the Australian government has clearly established a need to place legislative protections and oversight around this most contentious of powers. Yet much more research needs to be conducted into determining appropriate policy controls and thresholds at which certain methodologies might be employed under SDA data disruption and ASIO computer access warrants.

Fourthly, Australia’s data disruption warrant regime needs to be deconflicted from the perspective of ASD. Given its unique position as an IS Act agency, as well as an agency that supports military operations and law enforcement, the precise jurisdiction of ASD operations conducted in a domestic environment (i.e., inside Australian territory or against Australian residents or citizens) needs to be narrowed down with far greater precision. A Ministerial direction is perhaps the most appropriate action in that case.

In concluding, we also observe that our examination of “hacking back” focuses solely on the Australian experience, and neglects that of the other Five Eyes countries with whom they may share methodology (New Zealand, Canada, US and UK). We also have not considered the actions or examined the legitimacy of others active both in cyberspace and the Indo-Pacific region we share, such as Pakistan, India, China, North Korea or Singapore. Further, the voice of our intelligence agencies – represented in the form of empirical studies of their methods and techniques – is sorely lacking in the debate. All three areas are fruitful avenues for future research.

Yet in our jurisdiction there exists patchy legal frameworks in which security translates poorly from being a physical concept. Australia appears to have reconciled itself to the idea that its national security agencies – either ASD or the AFP – can hack into the computers of cybercriminals no matter where they are in the world, and no matter how challenging an intrusion into foreign sovereignty that may be. If those capabilities suffer from a lack of both transparent legality and legitimacy when theoretically applied to domestic threats, that is a situation that cannot be allowed to continue.

Alternately, though we seem more than capable of deploying “hacking back” capabilities, Parliament may have chosen the very deliberate means of excising them from being used inter alia to combat domestic threats. Given Australia’s uncertain future and contested geostrategic position in the Indo-Pacific, the importance of ensuring its national security agencies operate with the powers and functions they need within an appropriate accountability and regulatory framework, cannot be understated.

[*] Senior Research Fellow, T.C. Beirne School of Law, University of Queensland.

[†] Research Assistant, University of Queensland.

[‡] Lecturer in Cyber Criminology, School of Social Science, University of Queensland.

[1] Simon Benson, Geoff Chambers, ‘“Hack back” powers to repel cyber attack’, The Australian (online, 12 August 2020).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ry Crozier, ‘Australia sets up 100-strong permanent “operation” to target hackers’, IT News (online, 12 November 2022) <https://www.itnews.com.au/news/australia-sets-up-100-strong-permanent-operation-to-target-hackers-587691>.

[5] International Institute for Strategic Studies, Cyber Capabilities and National Power: A Net Assessment (Final report, 28 June 2021) <https://www.iiss.org/blogs/research-paper/2021/06/cyber-capabilities-national-power>, 15.

[6] Ibid, 10-12.

[7] Allie Coyne, ‘Australia has created a cyber warfare unit’, ITNews (online, 30 June 2017) <https://www.itnews.com.au/news/australia-has-created-a-cyber-warfare-unit-467115>; Jeremy Fleming, ‘Director's speech at Cyber UK 2018’ (Speech, CyberUK18 Conference, 12 April 2018), <https://www.gchq.gov.uk/pdfs/speech/director-cyber-uk-speech-2018.pdf>, 7; Michael S. Rogers, Evidence to Senate Committee on Armed Services, United States, 27 February 2018, <https://www.armedservices.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Rogers_02-27-18.pdf>, 1-3; National Defence (Canada), ‘Strong, Secure, Engaged: Canada’s Defence Policy’ (online), <https://www.canada.ca/content/

dam/dndmdn/documents/reports/2018/strong-secure-engaged/canada-defence-policy-report.pdf>, 41; Ed Caesar, ‘The Incredible Rise of North Korea’s Hacking Army’, The New Yorker (online, 19 April 2021) <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/04/26/the-incredible-rise-of-north-koreas-hacking-army>.

[8] Martin C. Libicki, Cyberdeterrence and Cyberwar (Report, RAND Corporation, 2009); Kenneth Lieberthal, Peter W. Singer, Cybersecurity and U.S.-China Relations (Washington DC, Brookings Institution, 2012); Adam P. Liff, ‘Cyberwar: A New ‘Absolute Weapon’? The Proliferation of Cyberwarfare Capabilities and Interstate War’ (2012) 35(3) Journal of Strategic Studies 401; Lucas Kello, ‘The Meaning of the Cyber Revolution: Perils to Theory and Statecraft’ (2013) 38(2) International Security 7; Timothy J. Junio, ‘How Probable Is Cyber War? Bringing IR Theory Back in to the Cyber Conflict Debate’ (2013) 36(1) Journal of Strategic Studies 125.

[9] James P. Farwell, Rafal Rohozinski, ‘The New Reality of Cyber War’ (2012) 54(4) Survival 107, 109; Mary Ellen O'Connell, ‘Attribution and Other Conditions of Lawful Countermeasures to Cyber Misconduct’ (2020) 10(1) Notre Dame Journal of International Comparative Law 1.

[10] Joint Chiefs of Staff, Cyberspace Operations (JP 3-12, Department of Defense, 8 June 2018) <https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/pubs/jp3_12.pdf>; Chiefs of Staff, Cyber Primer (Third edition, October 2022) <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/

system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1115061/Cyber_Primer_Edition_3.pdf>.

[11] Stephanie Carvin, ‘Zero D’Eh: Canada Takes a Bold Step Towards Offensive Cyber Operations’, Lawfare (blog, 27 April 2018) <https://www.lawfareblog.com/zero-deh-canada-takes-bold-step-towards-offensive-cyber-operations>.

[12] Tom Pullar-Strecker, ‘“Open secret” NZ has offensive cyber capability, security firm says’, Stuff (online, 1 December 2021) <https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/127156155/open-secret-nz-has-offensive-cyber-capability-security-firm-says>.

[13] Commonwealth of Australia, Australia’s Cyber Security Strategy 2020 (P-20-02344, 2020).

[14] Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Cth), Australia’s International Cyber Engagement Strategy (October 2017).

[15] Malcolm Turnbull, ‘Launch of Australia’s Cyber Security Strategy Sydney’ (Press Statement, 21 April 2016).

[16] Jackson Graham, ‘“Uncomfortable” debate about offensive cyber attacks increasingly public as security environment shifts’, The Mandarin (online, 22 November 2021) <https://www.themandarin.com.au/

175558-uncomfortable-debate-about-offensive-cyber-attacks-increasingly-public-as-security-environment-shifts/>.

[17] James P. Farwell, Rafal Rohozinski, ‘The New Reality of Cyber War’ (2012) 54(4) Survival 107, 113.

[18] Thomas Rid, ‘Cyber War Will Not Take Place’ (2012) 35(1) Journal of Strategic Studies 5; John Stone, ‘Cyber War Will Take Place!’ (2013) 36(1) Journal of Strategic Studies 101; Richard A. Clarke, ‘The risk of cyber war and cyber terrorism’ (2016) 70(1) Journal of International Affairs 179; Tarah Wheeler, ‘In cyberwar, there are no rules’ (2018) 230 Foreign Policy 34; Christopher J. Finlay, ‘Just war, cyber war, and the concept of violence’ (2018) 31(3) Philosophy & Technology 357.

[19] Valeska Bloch, Sophie Peach, Lachlan Peake, ‘The Hack Back: The Legality of Retaliatory Hacking’ (2018) 37.4 Communication Law Bulletin 8.

[20] Gavin Smith, Valeska Bloch, The hack back: The legality of retaliatory hacking (Blog, Allens Linklaters, 17 October 2018) <https://www.allens.com.au/insights-news/insights/2018/10/pulse-the-hack-back-the-legality-of-retaliatory-hacking/>.

[21] Jay P. Kesan, Ruperto P. Majuca, ‘Hacking Back: Optimal Use of Self-Defense in Cyberspace’ (2010) 84(3) Chicago-Kent Law Review 1; Benjamin Baker, ‘Considering the Potential Deterrence Value of Legislation Allowing Hacking Back’ (2018) SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3319530; Gabriel Martinez, Hacking Back: Self-Defense, Self-Preservation or Vigilantinism (PhD thesis, Utica College, 2020); Hannah Gallagher, ‘Recognising a Right to Hack Back-Tom and Jerry in Cyberspace?’ (2022) 25(1) Trinity College of Law Review 56.

[22] Tom Uren, Bart Hogeveen, Fergus Hanson, Defining Offensive Cyber Capabilities (Final report, ASPI, 4 July 2018) <https://www.aspi.org.au/report/defining-offensive-cyber-capabilities>. We also use the word “computer” broadly, as it can include mobile devices and Internet of Things (IoT) enabled systems.

[23] Ibid; Bloch, Peach & Peake, n 16; Gallagher, n 18; Josh Gold, The Five Eyes and Offensive Cyber Capabilities: Building a ‘Cyber Deterrence Initiative (Report, NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence, 2020); Brendan Walker-Munro, ‘White Hat, Black Hat, Slouch Hat: Could Australia’s Military Cyber Capability be Deployed against Threats Inside Australia?’ (2023) Federal Law Review, in proof.

[24] Tom Kulik, ‘Why the Active Cyber Defense Certainty Act Is a Bad Idea’, Above the Law (blog, 29 January 2018) <https://abovethelaw.com/2018/01/why-the-active-cyber-defense-certainty-act-is-a-bad-idea/>.

[25] Leonard Spector, ‘Cyber Offense and a Changing Strategic Paradigm’ (2022) 45(1) Washington Quarterly 38.

[26] Helen Wong, Cyber Security: Law and Guidance (Bloomsburg Professional, New York, 2018) [12.01].

[27] Dennis Richardson, Comprehensive Review of the Legal Framework of the National Intelligence Community (“the Richardson Review”) (Volume 1, December 2019) [3.71].

[28] Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS), Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), Australian Geospatial-Intelligence Organisation (AGO), Defence Intelligence Organisation (DIO), Office of National Intelligence (ONI), Australian Federal Police (AFP), Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC), Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC), and the Department of Home Affairs.

[29] D. L. Johnston, Defence Assistance to the Civil Community Policy (Department of Defence, 31 August 2021) 5.

[30] Cameron Moore, Crown and Sword: Executive power and the use of force by the Australian Defence Force (ANU Press, 2017) 169.

[31] As a result of the passing of the Surveillance Legislation Amendment (Identify and Disrupt) Act 2021 (Cth).

[33] IS Act, s 7.

[34] Ibid, s 7(1)(c).

[35] Ibid, s 7(1)(d).

[36] Australian Signals Directorate, Annual Report 2019-20 (Final report, Canberra, 12 October 2020) 29.

[37] Mamoun Alazab, ‘A new cyber taskforce will supposedly ‘hack the hackers’ behind the Medibank breach. It could put a target on Australia’s back’, The Conversation (online, 16 November 2022) <https://theconversation.com/a-new-cyber-taskforce-will-supposedly-hack-the-hackers-behind-the-medibank-breach-it-could-put-a-target-on-australias-back-194532>.

[38] Office of National Intelligence Act 2018 (Cth).

[40] ASIO Act, s 25A.

[41] Ibid, s 25A(2).

[42] Ibid, s 25A(3A)(c)-(e).

[43] Warwick McKean, ‘Searches and Sandwiches’ (1978) 37(2) The Cambridge Law Journal 200-202 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/4506084>.

[44] ASIO Act, s 4.

[45] If the data ‘appears to be relevant to the collection of intelligence by the Organisation in accordance with this Act’; ibid s 25A(3A)(b).

[46] Ibid, s 25A(4)(a) and (c).

[47] Ibid, s 25A(5).

[48] Ibid, s 27C(2).

[49] Ibid, ss 27C(3)(c)(ii) and 27E(4). Authorisations must be requested and granted in writing: ibid, s 27J(1) and (3).

[50] Ibid, s 27E(2)(c).

[51] Ibid, s 27E(5)

[52] Ibid, s 27A.

[53] And would therefore be the remit of other NIC agencies: IS Act, s 6, 6B and 7.

[54] ASIO Act, s 27A(1)(b).

[55] Ibid, s 27A(3D).

[56] IS Act, s 8 and 9.

[57] Ibid, ss 8(1)(a)(i), (iaa) and (ii).

[58] Ibid, ss 8(1)(a)(ia) and (ib).

[59] Ibid, s 8(1)(a)(iii).

[60] Broadly, see ibid, ss 9(1), (1A) and (1AAA).

[61] Ibid, s 6(1)(a) and (e).

[62] Ibid, s 6B(1)(a).

[63] Ibid, s 7(1)(c).

[64] Ibid, s 6(1)(c).

[65] Carl Anthony Wege, ‘Hizballah’s Counterintelligence Apparatus’ (2012) 25(4) International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence 771.

[66] IS Act, s 7(1)(da).

[67] Criminal Code, s 90.2.

[68] IS Act, s 7(1)(e)(i).

[69] Ibid, s 8(1B).

[70] Ibid, s 9(1)(c).

[71] In fact, s 4 of the ASIO Act includes ‘acts of foreign interference’, ‘espionage’ and ‘attacks on Australia’s defence system’ as matters of national security.

[72] Ibid, ss 6(1)(ba) (ASIS); 6B(1)(b), (c), (e) and 6B(2) (AGO); s 7(1)(ca), (d), (e) and 7(2) (ASD).

[73] Ibid, s 9(1)(a)-(c). Section 9(1)(d) does not apply, as the authorisation does not relate to activities of ASIO: ibid, ss 8(1)(a)(ia) and (ib).

[74] Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (Cth), s 8(1)(b)(i) and 8(1)(bf)(i).

[75] Ibid, s 7(1)(ca).

[76] Ibid, s 13(1)(a).

[78] Ibid, s 13A(1)(b) and (2).

[79] Greg Austin, ‘“Cyber revolution” in Australian Defence Force demands rethink of staff, training and policy’, The Conversation (online, 4 July 2017) <https://theconversation.com/cyber-revolution-in-australian-defence-force-demands-rethink-of-staff-training-and-policy-80317>.

[80] ASPI, n 19, 7.

[81] Marcus Thompson, ‘The ADF and Cyber Warfare’ (2016) 200 Australian Defence Force Journal 43; Jonathon C. Ladewig, ‘Australia’s Readiness for a Complex Cyber Catastrophe’ (2018) 14(2) Australian Army Journal 57; Ben Johanson, ‘Asymmetric Advantage in the Information Age: An Australian Concept for Cyber-Enabled “Special Information Warfare”’ (2018) 14(2) Australian Army Journal 79; Linda Reynolds, ‘Stronger cyber defences for deployed ADF networks’ (Media release, 12 August 2020) <https://www.minister.defence.gov.au/media-releases/2020-08-12/stronger-cyber-defences-deployed-adf-networks>; Australian Cybersecurity Magazine, ‘Australian Defence Force pilots cyber training program’ (online, 8 September 2020) <https://australiancybersecuritymagazine.com.au/australian-defence-force-pilots-cyber-training-program/>.

[84] Including the partner provision in the Australian Constitution, s 119.

[85] Samuel White, Andrew Butler, ‘Reviewing a Decision to Call out the Troops’ [2020] AIAdminLawF 11; (2020) 99 AIAL Forum 1, 58; Samuel White, ‘Keeping the Peace of the iRealm’ [2021] AdelLawRw 1; (2021) 42 Adelaide Law Review 1, 113

[86] Australian Constitution, s 68.

[88] R v Home Secretary of State for the Home Department, Ex parte Northumbria Police Authority [1989] 1 QB 26.

[89] Moore, n 29, 169.

[90] Being ‘a capacity to engage in enterprises and activities peculiarly adapted the government of the nation and which cannot otherwise be carried on for the benefit of the nation’: Victoria v Commonwealth and Hayden [1975] HCA 52; (1975) 134 CLR 338; Pape v Commissioner of Taxation [2009] HCA 22; (2009) 239 CLR 1.

[91] David Letts, Rob McLaughlin, ‘Military Aid to the Civil Power’, in Robin Creyke, Dale Stephens, Peter Sutherland (Eds.), Military Law in Australia (The Federation Press, Alexandria, 2019) 117-128.

[92] CPCF v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection & Anor [2015] HCA 1; (2015) 255 CLR 514.

[93] Cf. CPCF, where the High Court did not believe the Commonwealth could ‘having failed to enter through the front door...enter through the back door and in effect achieve the same result by that means of entry’: ibid, [141].

[94] Ibid, ss 33(3), 34(3), 35(3) and 36(3). The obligation is imposed by s 39(2), and subject to ss 39(3) and 40.

[95] Ibid, ss 40(1)(a)(ii) and 40(1)(b).

[96] Ibid, s 46(7)(i).

[97] Ibid, s 51D(2)(j).

[98] Ibid, s 51L(3)(h).

[99] Ibid, ss 46(1)(a), 46(5) and 46(7).