Indigenous Law Bulletin

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Indigenous Law Bulletin |

|

Intellectual Disability, Aboriginal Status and Risk of Re-offending in Young Offenders on Community Orders

Dianna T Kenny and Matthew Frize

Identifying factors that are associated with offending (these factors are called ‘criminogenic needs’) is an important step in the process of helping offenders desist from crime. Conventional analysis identifies eight key predictors, including a history of antisocial behaviour, antisocial personality pattern, antisocial cognition, antisocial associates, family / marital circumstances, (non)attendance at school or work, poor use of leisure or recreation time and substance abuse.[1] However, other key factors such as mental health/illness, intellectual disability and Aboriginal status need to be considered because of the over-representation of people with these characteristics in the criminal justice system. In this paper, we consider two of these factors – intellectual disability (‘ID’) and Aboriginal status.

The relationship between age, ID, the Aboriginal status of young offenders and the risk of re-offending is complex and poorly understood. Accordingly, Kenny and Nelson carried out a study in 2008,[2] examining court appearances and sentencing, criminogenic needs and risk of re-offending in 800 young offenders – 20% (n=153) of whom were Aboriginal – who were serving community orders with the NSW Department of Juvenile Justice.

From the research, the authors found that young people with an ID had a higher risk of re-offending than those without an ID and that those with an ID were also more likely to be younger and Aboriginal. For Aboriginal young offenders, there was no difference between those with and without an ID in risk category allocation or number of court dates. That is, being Aboriginal was the primary predictor of risk category allocation and number of court dates, regardless of intellectual disability. For non-Aboriginal young offenders, those with an ID had higher risk scores and more court dates. That is, for non-Aboriginal young offenders, having an intellectual disability was the primary predictor for risk category allocation and number of court dates. These findings indicate that Aboriginal young offenders and those young offenders with an ID may have special needs within the juvenile justice system.

In 2003, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimated the prevalence of ID in the general Australian community to be 2.7%;[3] in contrast, another study from the same year found that 17% of young offenders in NSW youth correctional centres had an IQ below 70,[4] the level at which a person can be said to have an ID. In fact, ID has been linked with offending[5] even when factors such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status, IQ test motivation and greater police detection of less intelligent offenders are taken into consideration.[6] However, the contribution of ID to offending is generally weak.

In their study, Kenny and Nelson found significant over-representation of ID in the sample of young offenders on community orders in NSW reported on in this paper.[7] Intellectual functioning was evaluated using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (‘WASI’),[8] a standard, brief and reliable test of verbal and non-verbal intelligence for individuals aged 6-89 years. The WASI contains four subtests: vocabulary, block design, matrix reasoning and similarities. These four subtests yield three intelligence quotients, verbal intelligence (‘Verbal IQ’), performance intelligence (‘Performance IQ’) and full scale intelligence (‘Full Scale IQ’). Adaptive functioning of young people was assessed using the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-II-Abbreviated (‘WIAT-II-A’) Composite Standard Score, which is an estimate of overall academic achievement in reading, spelling and mathematics. Both the WASI and the WIAT-II-A Composite Standard Score are based on a normative sample with an average score of 100 and standard deviation of 15.

In the study, 15%, or 119 of WASI Full Scale IQ scores fell into the range consistent with intellectual disability, that is, less than 70. Eleven percent of young offenders, or 87 respondents, scored less than 70 on both the WASI Full Scale IQ and the WIAT-II-A Composite Standard Score. This indicates that 11% of the young offenders on community orders in that sample had an intellectual disability. Previously reported differences between Verbal and Performance IQ of juvenile offenders were also replicated in this sample.[9] On average, young offenders had a Performance IQ 12 points higher than their Verbal IQ.

There were equal proportions reflecting sampling proportions of young men and women with IQs above and below 70 – 15% of male respondents and 17% of female respondents had an IQ below 70. Aboriginal young offenders were significantly more likely to have an IQ below 70 than non-Aboriginal young offenders (27.1% and 11.9% respectively).

Much of this over-representation can be explained by reference to the social and health disadvantages experienced by Aboriginal people in Australia.[10] For example, higher levels of violence and dangerous levels of alcohol consumption in Aboriginal communities[11] are likely to lead to higher rates of foetal alcohol syndrome and acquired brain injury in Aboriginal children.[12] Indeed, a key risk factor for ID is poor socio-economic status.[13] The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, for instance, estimated that Aboriginal Australians are 1.5 times more likely to have a disability (including physical, mental and intellectual) than non-Aboriginal Australians.[14] Further, in a 2005 study, it was found that, although Aboriginal people comprise 3.5% of the population in Western Australia, they represented 7.4% of all people registered for ID services in that state.[15] Research from the same year indicated that children born to Aboriginal women were 2.83 times more likely to have a mild to moderate ID and 1.67 times more likely to have a severe ID than non-Aboriginal children.[16]

Evidence of ID may also be more prevalent in Aboriginal people due to in-built cultural bias in IQ tests, which generally assess skills, such as vocabulary and general knowledge acquired in the dominant Western culture. Sattler recommends that, where there are significant cultural or language concerns, Performance IQ, a measure of non-verbal skills, should be used in place of a Full Scale IQ as it relies less on language.[17] When Performance IQ and a proxy measure of adaptive functioning, in this case, contact with the juvenile criminal justice system, was used in a 2003 study, the number of young people with an ID decreased from 17% to 10% for Aboriginal young offenders.[18] Sattler warns that attempts at ‘culture fair’ tests of intelligence have not adequately reduced cultural bias or been sufficiently valid and reliable as measures of intelligence. Moreover, the multiple cultures and languages within the Aboriginal Australian community make it difficult to develop an Aboriginal specific intelligence test, although there have been recent attempts to do so.[19]

Notwithstanding these valid concerns, in reading the survey results, one must consider not only the formal definition of ID, but also the actual level of intellectual functioning of young people who come into contact with the criminal justice system, whether Aboriginal or otherwise. That is, many young offenders who do not qualify for a formal diagnosis of ID may still be functioning within the range of ID and will therefore require a similar level of service as those who have qualified for the formal diagnosis.[20]

A higher risk of reoffending by Aboriginal people has been found in a number of countries.[21] In Australia, in 2005, Aboriginal adults were 13 times more likely to appear in court and 12 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Aboriginal adults.[22] Similarly, Aboriginal young people in Australia are 23 times more likely to be in youth detention than their non-Aboriginal peers (24 times more likely in NSW).[23] Further, while 52.6% of non-Aboriginal young people appearing in court in 1995 in NSW had at least one adult court appearance within eight years, 90.5% of Aboriginal young offenders had at least one adult court appearance over the same period of time.[24] Moreover, male Aboriginal young offenders who had been subject to supervision orders and care and protection orders had a nearly 100% probability of progressing from the youth to adult correctional system.[25]

Most of the research assigns only a minor role to ID when considering all the possible factors that lead to offending,[26] particularly for young offenders.[27] The above discussion indicates that Aboriginal people appear to be at higher risk of engagement with the criminal justice system and at higher risk of having an ID compared with non-Aboriginal people. However, Aboriginal offenders and offenders with an ID also appear to reflect those criminogenic needs seen in the general offending population.[28] Our study therefore explored the relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal young offenders with and without an ID to assess whether either or both of these factors increased the risk of reoffending.

Examination of our participants’ criminal records [29] showed that young people with an ID were more likely to have a larger number of court attendances, more recorded offences, more bonds/probation, committed more property offences and greater numbers of Apprehended Violence Orders compared with the young offenders who did not have an ID.

These young people were assessed for their risk of reoffending using the Youth Level of Service / Case Management Inventory: Australian Adaptation (‘YLS/CMI:AA’), a reputable instrument[30] assessing offence history, family circumstances / parenting, education, peer relations, substance abuse, leisure / recreation, personality / behaviour, and attitudes / orientation.

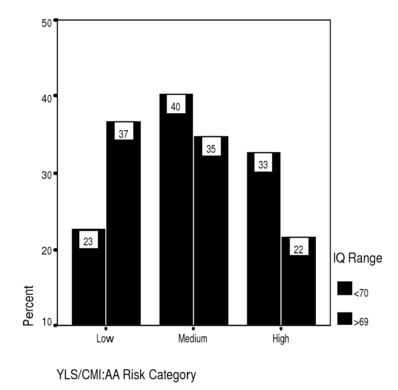

The average YLS/CMI:AA total score was 17.18, with a standard deviation of 9.4 for the total sample. This placed participants, on average, in the ‘medium risk’ category of reoffending. On average, those with an IQ below 70 scored in the ‘medium risk’ category and those with an IQ above 69 (not ID) scored in the ‘low risk’ category. The graph in Figure 1 shows the distribution of young offenders in each of the three risk categories according to whether or not they had an ID.

Statistical tests were conducted on these scores and found the following:

• Aboriginal young offenders were significantly younger (mean age = 16.58, SD = 1.34) than their non-Aboriginal counterparts (mean age = 17.09, SD = 1.25).

• ID young offenders (mean age = 16.62, SD = 1.29) were significantly younger than those without an ID (mean age = 17.06, SD = 1.27).

• There was no significant interaction between Aboriginality and ID status.

With respect to the YLS/CMI:AA total scores,

• Aboriginal young offenders had significantly higher scores (that is, were at higher risk) than non-Aboriginal young offenders;

• ID had significantly lower scores than non-ID young offenders;

• There was no significant interaction between Aboriginal and ID status.

Further,

• Those with an ID had similar court attendances regardless of Aboriginal status; but

• In the non ID group, Aboriginal young offenders had significantly more court attendances than non-Aboriginal young offenders.

From the foregoing, we can see that Aboriginal young offenders were significantly more likely to have an IQ below 70 than those who were non-Aboriginal. For Australian studies, higher prevalence of ID in those who offend may be associated with the high proportion of Aboriginal young people in offender samples. The high prevalence of co-occurring intellectual disability and Aboriginal status found in this sample has significant implications for service delivery.

Consistent with previous Australian research,[31] regardless of ID status, Aboriginal young offenders scored higher and were more likely to be in a higher risk category on the YLS/CMI:AA than non-Aboriginal young offenders. Aboriginal young offenders with an ID had higher risk scores than non-Aboriginal young offenders with an ID. However, those with an ID were found to be at a statistically higher risk of being allocated to a higher risk category if they were non-Aboriginal, hence indicating that ID may be a risk factor for offending behaviour. However, contrary to risk assessment of higher probability of re-offending, anecdotal evidence suggests that those who are Aboriginal or have an ID are often excluded from treatment services that target criminogenic needs.[32]

With respect to court appearances, Aboriginal young offenders with and without an ID had similar numbers of court attendances; for non-Aboriginal young offenders, those with an ID had significantly more court appearances. This discrepancy in number of court appearances cannot be readily explained and needs further exploration.

Consistent with previous research,[33] Aboriginal young offenders were younger than non-Aboriginal young offenders. Those with an ID were also younger than those without an ID and those who were both Aboriginal and ID were the youngest sub group. These findings have implications for early intervention programming. They suggest that programs targeting young offenders with an ID, or who are Aboriginal, need to be delivered in a manner that is suited to learning styles and support needs of younger offenders. With early age of offending being recognised as a significant risk factor for future offending,[34] these results reinforce the claim that priority should be given to these particular groups with respect to treatment that targets criminogenic needs.

This study shows that Aboriginality and ID status make separate and combined contributions to risk of re-offending in young offenders. Given the high prevalence and high risk of reoffending of Aboriginal young offenders, young offenders with an intellectual disability and intellectually disabled Aboriginal young offenders in the population of young offenders in NSW, priority should be given to these particular groups with respect to early interventions that target their specific criminogenic needs in an attempt to reduce their high re-engagement rates with the juvenile and subsequently adult criminal justice systems. Treatment services will need to ensure that they address the learning styles and motivation of Aboriginal and intellectually disabled young offenders. Given the young age of offenders, such services will need to consider how to interact with the family/carers of these young offenders as well as the social and economic difficulties that contribute to crime in Aboriginal communities.

Dianna Kenny (PhD MAPsS MAPA) is Professor of Psychology at the University of Sydney. She has engaged in extensive research into young offenders, working with partner organisations NSW Department of Juvenile Justice, Justice Health, Public Interest and Advocacy Coalition, and the Youth Justice Coalition. Her book, with Paul Nelson, Young Offenders on Community Orders: Health, Welfare and Criminogenic Needs (2008) is the first comprehensive study of community based young offenders in Australia.

Matthew Frize (M Forensic Psych) is a PhD student and a senior behaviour consultant with the Criminal Justice Program, Department of Ageing, Disability and Home Care, Parramatta, NSW, Australia.

[1]Don Andrews, James Bonta and J Stephen Wormith, ‘The Recent Past and Near Future of Risk and/or Need Assessment’ (2006) 52(1) Crime & Delinquency, 7-27.

[2] Dianna Kenny, Paul Nelson, Young Offenders on Community Orders: Health, Welfare and Criminogenic Needs (2008).

[3] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Disability Prevalence and Trends (2003).

[4] Mark Allerton, Dianna Kenny, Una Champion and Tony Butler, 2003 NSW Young People in Custody Health Survey: A Summary of Some Key Findings (Speech delivered at the Young Justice: From Lessons of the Past to a Road Map for the Future Conference, Sydney 2003).

[5] David Farrington, ‘The Twelfth Jack Izard Memorial Lecture: The Development of Offending and Antisocial Behavior from Childhood: Key Findings from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development’ (1995) (36) Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 929.

[6] Donald Lynam, Terrie Moffitt and Magda Stouthamer-Loeber, ‘Explaining the Relation between IQ and Delinquency: Class, Ethnicity, Test Motivation, School Failure, or Self-Control’ (102) Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 187.

[7] See Kenny and Nelson, above n 2.

[8] Assessed using The Psychological Corporation, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) (1999).

[9] Sheila Timms and Anthony Goreczny, ‘Adolescent Sex Offenders with Mental Retardation: Literature Review and Assessment Considerations’ 7(1) Aggression and Violent Behavior, 1.

[10] Jim Simpson and Mindy Sotiri, Criminal Justice and Aboriginal People with Cognitive Disabilities (2004).

[11] Tanya Chikritzhs and Maggie Brady, ‘Fact or Fiction? A Critique of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2002’ 25(3) Drug and Alcohol Review, 277; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Reported Injury Mortality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People in Australia, 1997–2000 (2004).

[12] Katrina Harris and Ingrid Bucens, ‘Prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome in the Top End of the Northern Territory’ 39(7) Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health.

[13] Maureen Durkin, ‘The Epidemiology of Developmental Disabilities in Low-Income Countries’ 8(3) Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 206.

[14] Australian Bureau of Statistics, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, 2002 (2004).

[15] Emma Glasson, Sheena Sullivan, Rafat Hussain and Allan Bittles, ‘An Assessment of Intellectual Disability Among Aboriginal Australians’ 49(8) Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 626.

[16] Helen Leonard et al, ‘Association of Sociodemographic Characteristics of Children with Intellectual Disability in Western Australia’ 60(7) Social Science and Medicine, 1499.

[17] Jerome Sattler, Assessment of Children: Cognitive Applications (4th ed, 2001).

[18] Allerton, Kenny, Champion and Butler, above n 4.

[19] Murray Dyck, ‘Cognitive Assessment in a Multicultural Society: Comment on Davidson (1995)’ 31(1) Australian Psychologist, 66-69.

[20] Kenny and Nelson, above n 2.

[21] Jeff Latimer and Laura Foss, ‘The Sentencing of Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Youth under the Young Offenders Act: A Multivariate Analysis’ 47(3) Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 481.

[22] Australian Bureau of Statistics. Prisoners in Australia (2005).

[23] Ibid.

[24] Shuling Chen, Tania Matruglio, Don Weatherburn and Jiuzhao Hua, ‘The Transition from Young to Adult Criminal Careers’ (2005) 86 Crime and Justice Bulletin.

[25] Mark Lynch, Julianne Buckman, and Leigh Krenske, Youth Justice: Crime Trajectories (2003).

[26] Don Andrews and James Bonta, The Psychology of Criminal Conduct (4th ed, 2006).

[27] Cindy Cottle, Ria Lee and Kirk Heilbrun, ‘The Prediction of Criminal Recidivism in Young Offenders: A Meta-Analysis’ 28(3) Criminal Justice and Behavior, 367.

[28] Lucy Snowball and Don Weatherburn, ‘Aboriginal Over-Representation in Prison: The Role of Offender Characteristics’ (2006) 99 Crime and Justice Bulletin; Don Weatherburn, Lucy Snowball and Boyd Hunter, ‘The Economic and Social Factors Underpinning Aboriginal Contact with the Justice System: Results from the 2002 NATSISS Survey’ (2006) 104 Crime and Justice Bulletin.

[29] For a detailed review of methods and tests used, see Kenny and Nelson, above n 2.

[30]Anthony Thompson and Z Pope, ‘The Conceptual and Psychometric Basis for Risk-Need Assessment’ 55 Australian Journal of Psychology, 216; Anthony Thompson and Z Pope, ‘Assessing Young Offenders: Preliminary Data for the Australian Adaptation of the Youth Level of Service/Case Management Inventory’ 40(3) Australian Psychologist, 207.

[31] Chen et al above n 24; Snowball Weatherburn above n 28; Weatherburn et al, above n 28.

[32] Simpson and Sotiri, above n 10.

[33] Natalie Taylor, Juveniles in Detention in Australia, 1981-2005 (2006); Weatherburn et al, above n 28.

[34] Randy Borum, ‘Managing At-Risk Young Offenders in the Community’ 19(1) Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 114; Chen et al above n 24.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IndigLawB/2010/19.html