Sydney Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Sydney Law Review |

|

Before the High Court

History and Counter-History: 25 Years of Writing for the High Court

Arlie Loughnan and Shae McCrystal[∗]

Abstract

In 1991, the Sydney Law Review commenced publishing a column discussing cases due to be heard by the High Court of Australia. On the 25th anniversary of the Before the High Court (‘BTHC’) column, this paper provides an overview of the history of the column, its genesis and a measure of the take-up of BTHC columns by the High Court and elsewhere. The BTHC column has been and remains significant, both as a facilitator of scholarly engagement with High Court decision-making, and as part of a wider tradition of legal academic writing for courts. The paper suggests that the BTHC represents both history — of academic analysis and arguments taken up by the Court — and counter-history — the alternatives or paths not taken at significant junctures in the development of law in Australia.

... a well-timed and carefully argued law review article may have [utility] for the development of the law [...]. [There is a] useful series published by the Sydney Law Review in its regular section ‘Before the High Court’. (That journal, the High Court Review and occasionally others, scrutinise problems presented for the law in cases in which the High Court of Australia has granted special leave to appeal.) [...] A first class law review article can therefore sometimes be very important.

Justice Michael Kirby[1]

It is 25 years since the Sydney Law Review (‘SLR’) published the first Before the High Court (‘BTHC’) column, which appeared in June 1991. In the period since its introduction, the BTHC column has become an integral component of the SLR. There has been at least one BTHC column in every volume of the SLR since the first column was published in 1991. There have been a total of 61 BTHC columns published in the intervening 25 years (including the one published in this issue), examining a total of 62 cases either arising out of the original jurisdiction of the High Court, or in which special leave to appeal to the High Court had been granted.[2] After a quarter of a century and 61 columns, the time is right to review the contribution made by the column.

This paper offers an overview of the origins of the BTHC column and its first 25 years. It presents an empirical study measuring the take-up of the column by the High Court of Australia, which shows that a significant proportion of BTHC columns were cited (in footnotes or in-text) by the High Court in the decision that formed the subject matter of the column, or in a subsequent High Court judgment. But, we suggest that the significance of the column does not reduce to citation rates. The BTHC column is a facilitator of scholarly engagement with High Court decision-making. As one of few dedicated interfaces between the Australian legal academy and the courts, the column encourages engagement by legal scholars with the activities of the High Court. Further, it is a part of a wider and long-standing tradition of academic writing for courts. Taking into account both cited and uncited columns, the BTHC column represents both history — of academic analysis and arguments taken up by the Court — and counter-history — the alternatives or paths not taken at significant junctures in the development of law in Australia.

The paper begins with a history of the BTHC column and the SLR. The second part of the paper presents an empirical study of the take-up of BTHC columns by the High Court, examining citation rates. The final substantive sections cover those BTHC columns uncited by the High Court, and the broader take-up of the BTHC column beyond the High Court, in decisions of other courts and in legal scholarship. The paper concludes by offering some brief reflections on the future of legal academic writing for courts.

The SLR is a generalist law review run under the auspices of the Faculty of Law at the University of Sydney. The Review was established in 1953 as a student-run journal managed by a student editorial committee in the style of United States law reviews, with the Antipodean twist of operating under the supervision of an editorial board and academic general editor. The originator of the SLR, and the academic general editor for its first seven years, was Professor Julius Stone. Professor Stone drew on his experiences at Harvard Law School in establishing the Review.[3] Faculty of Law students were responsible for SLR content, with the exception of the leading articles, and contributed a range of comments, case notes, legislative notes and book reviews.[4] SLR issues were published annually, with three issues to a volume, although publication of issues was at first sporadic.

The SLR was managed in this way until late 1973, when full responsibility for the Review was devolved to a student editorial committee, assisted by a management committee that included one member of the academic staff.[5] This change coincided with a broader change in Australian legal academia, as full-time academics came to replace part-time practitioners as law teachers, and law schools moved onto a firmer footing within universities.[6] The SLR continued formally in this fashion until 1990, when the Faculty took the decision to publish SLR issues quarterly (in annual volumes) and to vest responsibility for the Review in a faculty editorial board assisted by a student board of editors.[7] The first edition of the SLR to be published in this manner was the March 1991 edition. As in the 1970s, this change in the 1990s was part of a wider, cultural change in legal education in Australia. By this time, a wider view of law teaching and legal education (combining doctrine, practical skills classes and academic approaches to law) had come to the fore,[8] and scholarly publishing was coming to be more important in academic workloads, promotion criteria and institutional profiles.

The first BTHC column was published in the June 1991 edition of the SLR. The introduction of the column came at a crucial time in the evolution of the Review and was part of the shift toward academic control over the SLR. Professor James Crawford had been appointed as Dean of the Faculty of Law in 1990 and held a reformist outlook. During Crawford’s first year as Dean, the Faculty determined to assume control of the SLR, beginning with the decision to publish quarterly instead of annually. In the March 1991 issue, the SLR’s newly formed faculty Editorial Board, under the editorship of Professor John Carter, noted that quarterly publication offered regularity, continuity and the ability to publish significant and topical articles promptly.[9] In order to ensure ongoing student involvement in the SLR, a unit of study attached to the Review and open to law students in the Faculty was also introduced.[10]

Credit for the introduction of the BTHC column is generally attributed to James Crawford.[11] Judge Crawford recalls thinking of the title of the column (pun and all), noting that the idea for the column was to anticipate cases that were to be heard by the High Court and to outline options for the decision the Court was required to make — to get into print ‘before’ the matter was heard ‘before’ the Court.[12] In 1991, the Editorial Board noted the introduction of a new ‘special segment’ called ‘Before the High Court’ in which ‘commissioned comments on issues arising in cases pending before the High Court of Australia’ would be discussed.[13] The inclusion of such a column marked part of the move away from an SLR that showcased the work of senior law students, toward an SLR showcasing the work of academics, and providing an opportunity for academics to contribute topical pieces that could have a potential influence outside the confines of academia.

There is also some suggestion that the instigation of the column was the outcome of a broader conversation between some of the then sitting members of the High Court (three of whom were alumni of the Faculty of Law)[14] and members of the academy. Judge Crawford recalls that the title of the column was in part a response to a comment of then Chief Justice Mason to the effect that too much academic writing ‘chased’ decided cases and lacked influence.[15] While we were unable to locate the precise comment by Sir Anthony Mason to this effect, in a speech he gave at the School of Graduate Studies at the University of Melbourne in September 1995, four years after the introduction of the BTHC column, Mason noted that previously he had been critical of ‘the quality of much academic legal commentary’, too much of which was ‘simply descriptive of what had been said and decided in particular cases’.[16] However, Mason observed that the situation had now ‘changed for the better’ and he took some credit for encouraging the introduction of the BTHC column in the SLR, the purpose of which was to enable the column to form part of ‘the corpus of academic commentary available for consideration by the Court’.[17]

As this suggests, the BTHC column was introduced to meet a perceived need within Australian legal scholarship. It functions as a bridge between the court and the academy, a conduit between ‘town’ and ‘gown’. Unlike most legal academic writing, the BTHC column is written for a specific purpose and with a narrow audience in mind. The goal of the column is to provide an opportunity for academic commentary to influence the deliberations, reasoning and outcome in particularly significant High Court judgments. As such, the BTHC column is part of a specific genre of legal academic writing: that which is directed to courts, or other legal professional institutions and actors, and is intended to influence either the practice of the law or its development or reform. This genre of legal scholarly writing has a long history, particularly in common law jurisdictions, dating back to times in which the division of labour between scholars, on the one hand, and judges and others, on the other hand, was less clear-cut, and there was much more movement across the boundaries between the bar, bench and academy.[18] The BTHC column provides a dedicated interface between the Australian legal academy and the courts, and facilitates engagement by legal scholars with the decision-making of the High Court.

Because BTHC columns are intended to come to the attention of the court in advance of the point at which the matter is heard, the columns may have a relatively short life span, unless they are picked up subsequently in other court decisions or within the secondary literature. This creates a dilemma for academics considering authoring a BTHC column. The opportunity to influence the High Court may be tempting, but the unattractive prospect of judicial radio silence and potential rapid obsolescence for the published piece also looms large. Nonetheless, the possibility of assisting the High Court has attracted many academics and, in addition to commissioning columns from particular scholars well known for their work in different legal sub-disciplines, the SLR now receives a numbers of offers each year to write BTHC columns.

From an editorial perspective, the timing of BTHC columns is particularly challenging. As the goal of the BTHC is to provide academic commentary that may be considered by the High Court, it is important for the BTHC column to enter the public domain (and generally be available to the Court and counsel on both sides of the case) before the presentation of oral argument in the relevant case. This means that a column must be commissioned, written, refereed, copy edited and published between the date on which either special leave is granted or notification given that cases are ready for hearing in the original jurisdiction, and the hearing of the case. In the past, when High Court timeframes were generally longer than they are now, this may not have presented much difficulty. However, a number of previous editors of the SLR have observed that ensuring that BTHC columns make it into print before the relevant High Court hearing was the most difficult challenge in managing the column.[19] Not all columns appear in print before the hearing, but are still published and available in the public domain before the judgment is handed down.[20]

In the context of legal academic publishing in Australia, the BTHC column is an unusual creation. There are currently no other academic forums in Australia of a similar nature, although from 1995 to 2000 Bond University Law School published an e-journal, the High Court Review,[21] with a similar purpose. Melbourne University Law School currently publishes a blog providing analysis of High Court decisions entitled Opinions on High.[22] However, this blog provides information on cases currently before the Court and discussion of decisions once made — generally it does not offer discussion and commentary on cases before they are decided by the Court.

Having reflected on the history of the BTHC column, and the difficulties attendant on writing and publishing such an unusual column, the discussion will now turn to the impact that the column has had in practice, in particular with respect to citations in the High Court. The column is a longstanding feature of the SLR and, as such, members of the High Court, through the High Court library, will be alerted to the column relevant to a particular case when it is published. Thus, the column comes to the attention of the Court on a more routine basis than other academic scholarship might do. The question that this raises for discussion is the degree to which this translates into impact in practice.

As mentioned above, the first BTHC column was published in June 1991.[23] It was written by Andrew Stewart, on the appeal to the High Court from a Full Bench of the Australian Industrial Relations Commission in the case World Square Pty Ltd v Federated Engine Drivers’ and Fireman’s Association of Australia.[24] As with all BTHC columns, the case was significant in its context (industrial relations), raising the issue of the meaning of the ‘prevention’ of interstate industrial disputes in s 51(xxxv) of the Australian Constitution. However, disappointingly for the first BTHC column, before the matter could be heard by the High Court, the underlying dispute was settled and the matter did not proceed. The second BTHC column,[25] published in December 1991, fared slightly better. It was written by Graeme Cooper, on the appeal to the High Court from the Full Federal Court decision in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Mount Isa Mines Ltd.[26] The case involved the issue of income tax deductions and, in particular, whether the costs of demolishing certain structures were income tax deductible by a mining company. The column was mentioned by counsel for the appellant in oral argument,[27] but was not subsequently cited by the High Court. It was not until 1994 that a BTHC column was cited by the High Court. In Health Insurance Commission v Peverill,[28] the sixth BTHC column published in December 1992 and written by Peter Hanks,[29] was cited by Mason CJ, Deane and Gaudron JJ in their joint judgment with respect to an aspect of public policy underlying the regulation of Medicare funding.[30]

Since the early years, our research indicates that at least a further 20 BTHC columns have been cited by the High Court in the case for which the column was written. The most recent citation was in September 2015, when Gageler and Nettle JJ in D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc[31] referred to and quoted from the corresponding BTHC column written by Brad Sherman.[32] In terms of the overall citation rate in High Court judgments of the BTHC column in the case for which the column was written, in the 61 columns published over the 25 year period from 1991 to 2015, 62 cases were discussed. Of these 62 cases, 21 judgments made reference to the relevant BTHC column, 34 judgments made no reference to the relevant BTHC column, five matters were discontinued either before the High Court hearing or judgment, and one judgment and one hearing were pending at the time of writing. Further, three BTHC columns were mentioned in submissions to the High Court by counsel and noted in the record of counsel submissions contained in the Commonwealth Law Reports.[33]

It is also notable that some BTHC columns have had a longer life span ‘before the High Court’ than originally intended. We know of at least three BTHC columns that were cited in High Court cases other than the one for which they were originally written. This includes two columns that had already been cited by the High Court in the corresponding case,[34] and one column where the corresponding High Court case had been discontinued.[35]

In our empirical study of citations of BTHC columns in the corresponding High Court case (which excludes the citation of at least 3 columns in later High Court cases), we found that 21 BTHC columns were cited 66 times in

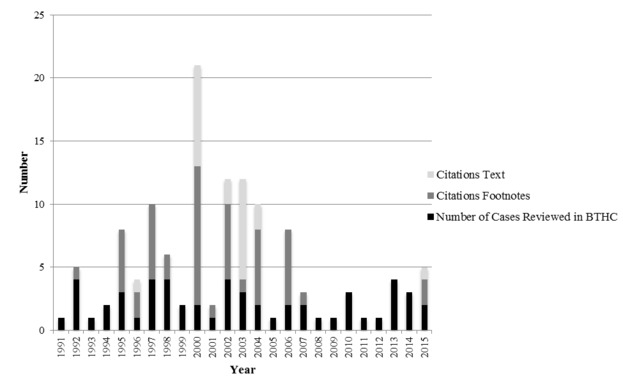

21 judgments. These citations were then grouped into two subcategories — footnote citations and in-text citations. Citations were classified as ‘footnote’ where the column was cited in a footnote as a source of authority for a factual or legal point, or mentioned as a contrasting perspective on the point made in the text. Citations were classified as ‘in-text’, where the citation involved an express mention of the author or the column, a direct quote from the column or, in some cases, a more oblique discussion of the argument raised in the column that appeared to us to have been attributed to the column, or to ‘commentators’ in general, including the columnist. Citation rates, classified on this basis, are illustrated by Figure 1.

Within Figure 1, the black shading represents the number of High Court cases dealt with by BTHC columns in a particular year, where the cases under review were not otherwise discontinued before judgment. Also excluded from the black shading are the two BTHC columns where the High Court proceedings are continuing and no judgment had been delivered at the time of writing. The dark grey shading represents the number of times those BTHC columns within that given year were cited in footnotes in the consequent High Court judgment, and the light grey shading represents in-text citations in the consequent High Court judgment, identified according to the definition outlined above.

We want to be clear about precisely what the level of citations does (and does not) reveal. The citation rate of the BTHC column by the High Court does not tell us whether the column has been successful in ‘influencing’ High Court decision-making over the past 25 years. It is difficult to be precise about influence and we avoid using the term here. In most cases, neither legal argument nor the Court’s decision-making process are fully reported so it is impossible to know what has been considered.[36] Further, influence implies a straightforward, unidirectional relationship that would discount the possibility that a particular piece provided a counterweight, or textual interlocutor, in the process of decision-making. We return to this point below.

Citation rates do provide some indication of the extent to which the BTHC column is coming to the attention of members of the Court when deciding cases on which the column reports. Of those cases where reference was made to the relevant BTHC column, frequency of citation varied according to whether reference to the column was made as footnote citation or made as in-text citation. As shown in Figure 1, the high point of in-text citation occurred between 2000 and 2006. This high point was not accounted for by the number of cases reviewed in BTHC columns during the particular year in question. For example, as can be seen with reference to 2000, eight in-text citations and 11 footnote citations were made in respect of two cases covered by BTHC columns, compared to 2002 in which four cases yielded two in-text citations and six footnote citations. Between 1991 and 1998, citation was limited primarily to footnotes. Footnote citations made up 70% of all citations, while in-text citations accounted for 30% of citations.

Figure 1: Number of cases reviewed by the BTHC column

and subsequent citations of BTHC columns in judgment, by year

The Court’s overall citation of the BTHC column (including in-text and footnote citation) peaked in the years spanning 1995 to 2007. Only one BTHC column has been cited by the High Court since 2008. Peak periods of citation were associated with Kirby J’s term on the High Court. Indeed, the data suggests that many of the citations were generated by a small group of High Court Judges; notably, Kirby J and, to a lesser degree, his contemporaries, Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron, McHugh, Gleeson, Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ. Since Kirby J retired from the Bench in 2009, only Gageler and Nettle JJ have cited a BTHC column in a judgment.

Citation rates are one metric that can be used to indicate the extent to which High Court judges have demonstrated awareness of the BTHC column, but of course they do not tell the whole story. It is difficult to estimate or measure the extent to which any particular BTHC column (or indeed any piece of academic writing) impacts on a judge or a court. As is well known, judges (particularly of appellate and apex courts) read widely, and inform themselves about legal matters in general from a variety of sources.[37] In the case of the BTHC column, it may be that a particular column has either been read or considered in a judgment, even if it has not been cited by the Court, or referred in a footnote citation. However, it is easier to support a claim that columns have been significant where they have been considered in-text, or where the column has been quoted directly. This involves 30% of the 21 BTHC columns that were cited. In relation to the overall number of BTHC columns published, nine out of the 54 columns (16%) that could have been cited[38] were cited 22 times in-text in the relevant High Court decisions.

It is not only through citation rates that we are able to establish that the BTHC column has had success in gaining the attention of the Court. The impact of particular BTHC columns in the corresponding High Court judgment has been noted and discussed in the secondary literature. First, Barbara McDonald’s 2000 BTHC column[39] on Brodie v Singleton Shire Council; Ghantous v Hawkesbury City Council[40] is discussed by Michael Kirby in a 2002 article in the Melbourne University Law Review.[41] Kirby notes that the column was ‘cited with approval in the joint judgment of Gaudron, McHugh and Gummow JJ in Brodie v Singleton Shire Council, and in my own reasons, both for the author’s analysis and for the opinions she expressed’.[42] Kirby identifies McDonald’s column as an ‘illustration of the utility that a well-timed and carefully argued law review article may have for the development of the law’.[43] Second, Michael Handler’s 2003 BTHC column[44] on Network Ten Pty Ltd v TCN Channel Nine Pty Ltd[45] is discussed by Lionel Bently and Brad Sherman in their intellectual property textbook, noting that the majority in the case ‘drew heavily’ on Handler, while ‘the minority, especially Kirby J, sought to refute Handler’s argument’.[46] Finally, Kimberlee Weatherall’s 2004 BTHC column[47] on Stevens v Kabushiki Kaisha Sony Computer Entertainment (Stevens)[48] is identified by David Brennan in an article discussing the Stevens decision as being a source adopted and relied upon by Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ in a joint judgment, and McHugh J in a separate judgment.[49]

Direct in-text citation, backed up by recognition of and discussion about the influence of a BTHC column in the secondary literature or, in the case of the McDonald BTHC column, in extra-curial writing from one of the High Court justices from the decision itself, allows us to make some claims about impact. Based on our research, we are able to state with some confidence that around 16% of the BTHC columns for which there is a corresponding High Court decision has had some level of impact on some High Court justices, even if just to reinforce their own thinking on a particular issue or to draw to their attention relevant material.

It is more difficult to make any claim with respect to the further 12 BTHC columns (20% overall) that were cited in the footnotes. In these cases, it is at least clear that the relevant High Court justice (most commonly Kirby J) was aware of the BTHC column and, as such, the column was reaching its intended audience. For the remaining 33 columns (excluding those where there was no High Court decision), the absence of a citation in the relevant judgment does not necessarily mean that the High Court justices were unaware of the existence of the column, or had not read or engaged with it. In fact, given the likelihood that the Court’s attention will have been drawn to the column by the High Court library, it would be highly unlikely that they were unaware of any particular column. The mere absence of a citation cannot be taken as implying a total absence of impact. However, without undertaking extensive qualitative empirical research involving interviews with former and sitting High Court judges, it is not possible to make any kind of assessment of this kind.

The wider context for our assessment of the take-up of the BTHC column by the High Court is the practice of the Court, and judges more generally, of reading and citing academic writing. The period in which it was regarded as inappropriate to cite a living scholar has receded well into the past.[50] Empirical research on the High Court suggests that there has been a steady increase in citations of academic work over time.[51] As echoed by our own study, this research suggests that rates of citation of academic work vary significantly between judges.[52] This variation, and change in judicial practice over time, has prompted comment and debate among members of the bench, and by academics, about the value (or disvalue) of university law reviews.[53] For our purposes here, it is sufficient to note that positive comments about the utility to the Court of academic writing in law reviews have been made by several Australian judges.[54] The BTHC column is clearly part of the vitality of this ongoing interchange between the bench and the academy.

On the basis of a belief that the value of the BTHC column does not reduce to its rates of citation, we turned our attention to those BTHC columns that were not cited by the High Court in the case for which they were written.[55] As mentioned above, of the 61 BTHC columns published since 1991, discounting two columns where High Court proceedings are ongoing and five columns where the relevant High Court proceedings were discontinued, 33 have not been cited by the High Court. Because a higher number of BTHC columns published since 2008 have not been cited, this group is dominated by more recent columns, but, like those BTHC columns that were cited by the Court, our research indicated that these columns spanned the range of legal sub-disciplinary fields.

In order to assess whether there was a particular reason BTHC columns might not be cited by the High Court, we undertook a qualitative study of a subset of the uncited columns. We sought to test the hypothesis that uncited columns were, on the whole, columns that revealed a substantive disagreement with the High Court. A sample of just over one-third of the total number of uncited BTHC columns (13 of 33, or 39%), selected to span legal sub-disciplinary boundaries, were reviewed and compared with the corresponding High Court judgment. While this qualitative study examined only a subset, it allows us to offer some (qualified) observations about this group of BTHC columns.

The findings of our qualitative study suggested that while there was some evidence to support our initial hypothesis, the picture in practice was more complex. Our findings indicated that, in just under one-third of the sample of uncited BTHC columns, the High Court judgment evidenced substantive disagreement with the BTHC author. Significantly, just over one-third of the sample of uncited BTHC columns revealed that the Court’s judgment was made on a narrower base than that adopted by the BTHC author. The remaining BTHC columns in this sample — just under one-third — indicated broad agreement between the High Court decision and the relevant BTHC column (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sample of uncited BTHC columns

|

Category

|

BTHCs

|

Number

(n = 13)

|

% of total sample

|

|

High Court decision shows substantive disagreement with BTHC

|

• Smith v Western Australia (2014)

• Bugmy v The Queen [2013] HCA 37; (2013) 249 CLR 571

• Commonwealth of Australia v Barker [2014] HCA 32; (2014) 253 CLR 169

• Ruddock v Taylor (2005) 222 CLR 612

|

4

|

31%

|

|

High Court decision made on a significantly narrower basis than BTHC

|

• Honeysett v The Queen (2014) 253 CLR 122

• Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZSCA

(2014) 314 ALR 514

• Wingfoot Australia Partners Pty Ltd v Kocak [2013] HCA 43; (2013) 252 CLR

480

• Hogan v Australian Crime Commission [2010] HCA 21; (2010) 240 CLR 651

• Puttick v Tenon Ltd (formerly Fletcher Challenge Forests

Ltd) [2008] HCA 54; (2008) 238 CLR 265

|

5

|

38%

|

|

High Court decision shows broad agreement with BTHC

|

• Amaca Pty Ltd v Ellis; State of South Australia v

Ellis; Millennium Inorganic Chemicals Ltd v Ellis [2010] HCA 5; (2010) 240 CLR

111

• Commissioner of Taxation of the Commonwealth v BHP Billiton

Finance Ltd [2011] HCA 17; (2011) 244 CLR 325

• Akiba on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim Group v

Commonwealth of Australia (2013)

• Roach v Electoral Commissioner [2007] HCA 43; (2007) 233 CLR 162

|

4

|

31%

|

The first group of BTHC columns in the sample of uncited columns revealed substantive disagreement between the High Court decision and the BTHC column. Here, a useful example is the BTHC column by Joellen Riley,[56] and the corresponding High Court decision of Commonwealth of Australia v Barker.[57] This case concerned the then unresolved issue of whether Australian law recognised a duty to uphold ‘mutual trust and confidence’ in the employment relationship. Riley argued that the obligation of mutual trust and confidence should be recognised in Australian law as an aid in the interpretation of employment contracts. In its decision, the High Court refused to recognise the obligation of mutual trust and confidence, concluding it was not a part of the law of Australia. Interestingly, a number of academic sources were cited by the Court in this case, but those sources were almost exclusively commentary from the commercial or contract sphere with respect to the obligation of good faith in contracts in general, as opposed to any Australian labour law scholarship on the issue of mutual trust and confidence. In addition to substantive disagreement between the approach taken in the BTHC column and the High Court judgment, this comparison also indicates a difference in framing, with the Court taking an approach grounded in general contract law as opposed to the labour law framework advanced by Riley.

Another example in this category is the BTHC column on Ruddock v Taylor[58] by Susan Kneebone.[59] This case concerned Mr Taylor, a long term British migrant, whose visa had been cancelled on two separate occasions, and who sued the Minister for Immigration, Philip Ruddock, for false imprisonment for the periods he spent in immigration detention following the cancellation of his visa. The New South Wales Court of Appeal had affirmed the liability of the Minister to pay damages to Mr Taylor for false imprisonment, and the Commonwealth appealed. The question for the High Court was whether immigration officers could reasonably suspect Mr Taylor of being an unlawful alien, and whether they could be held to be exercising their powers independently and lawfully. By a majority, the High Court confirmed that the officers had lawfully exercised their power to detain someone reasonably suspected of being an unlawful non-citizen, and overturned the award of damages paid to Mr Taylor. In her BTHC column, Kneebone had made a case that the Court of Appeal decision should be upheld by the High Court, on the basis that the officers were not exercising independent powers, but following directions of the Minister, and that Mr Taylor’s detention was the result of unlawful exercises of power.[60] Kneebone mounted a strong argument that ranged widely over the law governing the tort of false imprisonment, and the exercise of personal powers by the Minister under the Migration Act 1958 (Cth), but the judges in the majority separated the issue of the power to detain unlawful non-citizens under the Act from the Minister’s exercise of power, and focused on the former, and this focus on statutory power eclipsed the tort issue.

To the extent that analysis and arguments presented in BTHC columns run contrary to that of the High Court, we suggest that BTHC columns in part provide a counter-history of High Court jurisprudence, indicating paths not taken at significant junctures in the development of Australian law. In this sense, those columns that were uncited by the Court might turn out to be as significant as those that made it into the footnotes or the text of the judgment(s). Indeed, it can plausibly be suggested that, should any of the decisions that formed the subject-matter of a BTHC column be overturned in future years, the corresponding BTHC columns might enjoy a second bite at the legal cherry.

We suggest that the subset of uncited BTHC columns argued on a substantially broader base than that adopted by the High Court should be included in this counter-history stream. As mentioned above, over one-third of the sample of uncited BTHC columns revealed that the High Court had decided on a narrower basis than that on which the author had argued. In their writing for courts (and more generally), academics are free to range more widely than a judge who normally depends on recognised legal authorities as presented to him or her by counsel. However, this free ranging analysis will not necessarily find favour with a Court tasked with deciding a discrete issue. This is because the common law develops incrementally — case by case, issue by issue — and judges generally try to confine themselves to the issues in the case as that is where they have had the benefit of self-interested argument by counsel. Thus, the Court may hesitate to cite a BTHC column with which it does not agree to ensure that nothing could be read into a reference to a piece that makes a broader argument.

From our study, an example suggestive of this issue is provided by the decision of Wingfoot Australia Partners Pty Ltd v Kocak,[61] and the BTHC column on it, written by Matthew Groves.[62] The issues that arose in Wingfoot v Kocak provided the High Court with an opportunity to reconsider the common law rule that there is no general duty to provide reasons for administrative decisions. Groves’ BTHC column argued that the rule at common law should be revisited on the basis of a comprehensive assessment of the criticisms of the common law rule, its qualification by the introduction of statutory duties to give reasons, and an assessment of relevant developments in international law. However, in its unanimous decision, the High Court confined itself to construction of the relevant statute at issue in the case and did not consider whether the common law should be changed. The Court commented:

General observations, drawn from cases decided in other statutory contexts and from academic writing, about functions served by the provision of reasons for making administrative decisions are here of limited utility. To observe, for example, that the provision of reasons imposes intellectual discipline, engenders public confidence and contributes to a culture of justification, is to say little about the standard of reasons required of a particular decision-maker in a particular statutory context.[63]

As this comment suggests, ‘general observations’ may be insufficiently targeted to the issue at hand. But it is also possible to envisage a scholarly analysis in which its breadth is its strength. In this respect, the analysis presented by some BTHC authors may prove significant because it is wide-ranging, encouraging the Court to consider a particular issue in a wider perspective. As Kirby J writes, ‘sometimes, at their best, law review articles will permit exploration of ideas by a judge free from the constraints of authority that must be obeyed in deciding a particular case’.[64]

The final group of uncited BTHC columns in our sample evidenced broad agreement with the reasoning of the High Court. Here, a useful example is provided by Lauren Butterly’s BTHC column, ‘Clear Choices in Murky Waters’,[65] which concerned the High Court decision of Akiba on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim Group v Commonwealth of Australia.[66] There were two issues before the Court: whether native title rights to commercial fishing had been extinguished, and whether reciprocal native title rights are able to be recognised. The High Court held that particular enactments by colonial and state legislatures in Queensland and by the Commonwealth Parliament had not extinguished the native title rights of Torres Strait Islanders to fish the resources of the Torres Strait. The High Court held that legislation may regulate the exercise of native title rights and interests without affecting the right to any further extent. The Court also held that reciprocal rights were dependent upon status and not rights in relation to land or waters. When this decision is compared with Butterly’s BTHC column, it becomes clear that the High Court shared Butterly’s views on the regulation of rights. Butterly took a distinct approach regarding reciprocal rights that arise from personal relationships between groups. While she acknowledged that ‘[t]he simple answer must be that only rights in relation to land and waters can be claimed under the [Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)]’[67] (which was the approch taken by the Court), she went on to note that there was nothing to prevent the Seas Claim Group from arguing that the relevant rights are ‘in relation to’ waters although they are held pursuant to a personal relationship — positing that if the argument was put a different way, then it may be successful.

It is not possible to say anything definitive about the significance or otherwise of the final subset of uncited BTHC columns that, like Butterly’s, converged with the reasoning adopted in the judgment of the High Court. It is certainly possible that these BTHC columns were read and engaged with by members of the Court. However, the absence of citation in such circumstances may suggest a lack of significance or that the column was simply not read by counsel or the Court.

Overall, our qualitative analysis of a sample of uncited BTHC columns supports our suggestion that one reason why a significant proportion of BTHC columns are uncited is because the author has taken a meaningfully different approach to that ultimately adopted by the Court. This was the case for more than two-thirds of the columns in our sample, comprising those that substantially disagreed with the approach ultimately taken by the Court, and those where the author adopted a broader approach to the issues at stake in the case. The ongoing value of these BTHC columns lies in the realm of counter-history, alternative analyses outlining a path not taken by the High Court in the development of Australian law.

Some BTHC columns have gone on to enjoy further impact either in the context of other decisions (both in Australia and overseas) or within the scholarly literature.

In this part of our research, we relied on assistance from BTHC authors as this information was not easily discoverable. We contacted former BTHC authors asking them if they knew whether their BTHC column(s) had been cited in primary or secondary material, and, if so, where. Of the 62 BTHC authors,[68] 24 responded to the request for information.[69] Of the 24 responses we received, 7 indicated that they were unaware of whether their BTHC column had been cited in further primary or secondary materials, with the remaining 17 indicating that their column(s) had been referred to in a variety of media (representing 27% of all BTHC columns).[70]

It would serve little purpose here to catalogue all of the responses to our request, and set out the wide range of secondary literature in which different BTHC columns have been cited. However, it is useful to identify the columns that, to the limited extent of our knowledge, have been cited by courts other than the High Court, and to give a few illustrations of the impact that some columns have gone on to have long after the High Court decision was handed down.

In terms of citation by other courts, two BTHC columns have been cited in overseas jurisdictions. Anne Twomey’s 1997 BTHC column[71] on Levy v State of Victoria[72] and Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation[73] was cited twice in the footnotes of Levy,[74] but was also quoted by the Supreme Court of India in Union of India v Naveen Jindal.[75] Further, although the relevant High Court case was discontinued, the BTHC column by Catherine Dauvergne and Jenni Millbank, published in 2003,[76] was raised in counsel’s submissions and quoted by Gleeson and Spencer JJ in the UK Upper Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber) in SW v The Secretary of State for the Home Department.[77] Other BTHC columns have been cited in the Federal Court of Australia,[78] the Queensland Court of Appeal[79] and the Victorian Supreme Court.[80]

Outside the judicial arena, 14 BTHC columns were identified by their authors as having been cited or discussed within the secondary literature, in some cases, extensively. Again, it serves little purpose here to catalogue these BTHC columns, or the sources in which they have been cited. However, some general comments are appropriate. Our research has demonstrated that BTHC columns have been cited in a wide range of sources, across various legal disciplines, including international and national journals, textbooks, legal monographs and chapters in edited collections. Furthermore, some columns appear to have been the impetus for further scholarly writing and stimulus for debate within the secondary literature. There has even been one BTHC column where the author disagreed with the approach taken by an earlier BTHC column. In her 2012 BTHC column[81] with respect to Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission,[82] Megan Richardson argued that the earlier BTHC column[83] on Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Ltd,[84] by Robert Burrell and Kimberlee Weatherall, had been too law-focused and not sufficiently cognisant of policy issues.[85]

Finally, given that the BTHC column offers academics the opportunity to outline how they believe that the High Court should decide a particular case, and thus to reimagine the state of the law, it is unsurprising that BTHC columns have been cited in submissions to law reform agencies and in law reform reports. There are at least two examples. Jeremy Gans’s 1997 BTHC column[86] on Palmer v The Queen[87] was discussed in the Victorian Law Reform Commission’s Jury Directions Consultation paper in 2008.[88] Lauren Butterly’s 2013 BTHC column,[89] discussed above, was subsequently cited in an Australian Law Reform Commission Report on the Review of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).[90] Last, and perhaps furthest afield, in a category of impact all its own, Jeremy Gans’ 2002 BTHC column[91] on De Gruchy v The Queen[92] a case involving the murder of the juvenile defendant’s mother, brother and sister is included as a resource for HSC Legal Studies Students in NSW.[93]

This wider take-up of BTHC columns — by courts other than the High Court — and the evidence of their contribution to scholarly debate and law reform discussion reinforces the relevance of conceptualising the impact of the column in a broad way. This wider impact of BTHC columns demonstrates the broader value of the column in generating debate, discussion and contributing to legal scholarly analysis. This is arguably particularly significant given the discrete focus of BTHC columns. This is also further support for a premise of this paper: that the impact of the BTHC column extends beyond citation rates to include its reach into the academic domain in general, as well as to other courts and law reform bodies. Given the role of these agencies in the development and reform of the law, and the ongoing importance of vibrant legal scholarship for Australia’s legal future, the possibility of legal development or change arising from the BTHC column is manifest.

This article has provided an overview of the history of the Before the High Court column. The BTHC column has been and remains significant, both as a facilitator of scholarly engagement with High Court decision-making, and as part of a wider tradition of academic writing for courts. We suggested that the BTHC column represents history — of academic analysis and arguments taken up by the Court — and counter-history — the alternatives or paths not taken at significant junctures in the development of law in Australia. By way of conclusion, we offer some brief reflections on the possible future of legal academic writing for courts.

As mentioned above, the BTHC column is a particular instance of a specific genre of legal writing: writing for judges and other legal practitioners that is intended to influence the practice, development or reform of the law. To the extent that this genre sits within the broader category of doctrinal legal scholarship, it represents the main legal scholarly tradition in Australia. In the current era, however, following the influence of both the law and society movement, and critical legal studies, from the 1960s and 1970s, the legal academy now generates a huge variety of types of legal scholarship, including theoretical, historical, comparative, empirical and interdisciplinary work. This change has developed the critical, public policy and international orientation of legal scholarship, and meant that the audience of legal academic work may well be other scholars in law or cognate disciplines, other government agencies or actors, or a mixed and international audience.[94] Indeed, the period under discussion in this paper broadly coincides with the professionalisation of the Australian academy, and the concomitant rise to dominance of national research assessment exercises, according to which the quality of academic outputs is measured via peer review. The effect of this development is to reinforce the significance of internal norms and goals in the academy.

The future of academic writing for courts is likely to be bright, however. The drivers that gave rise to the BTHC column — the need for academic commentary that judges find useful, the importance of constructive engagement with judicial decision-making, and academic desire for relevance and real-world impact — are just as vital now as they were in 1991. Indeed, the emergent nature of ‘impact’ measures as part of research assessment exercises in Australia may well renew academic interest in, and enthusiasm for, specific channels for communication with the courts like the BTHC column.[95] As for the reception of such efforts on the part of the High Court (and other courts), the dearth of citations of BTHC columns in the years since 2008 does not necessarily indicate that the column will not find greater favour in its next 25 years. The role of individual judges (such as Kirby J) in citing the column (and academic writing more broadly) indicates that changes on the bench may also herald changing fortunes in the citation of BTHC columns.

Andrew Stewart, ‘Industrial Disputes and the Prevention Power: The World Square Case’ [1991] SydLawRw 15; (1991) 13(2) Sydney Law Review 199.

Graeme Cooper, ‘The Treatment of Demolition Expenses under the Income Tax: The Mount Isa Mines Case’ [1991] SydLawRw 33; (1991) 13(4) Sydney Law Review 605.

R Graycar, ‘Women’s Work: Who Cares?’ [1992] SydLawRw 4; (1992) 14(1) Sydney Law Review 86.

T R S Allan, ‘Discovery of Cabinet Documents: The Northern Land Council Case’ [1992] SydLawRw 16; (1992) 14(2) Sydney Law Review 230.

Brian Opeskin, ‘Conflict of Laws and the Quantification of Damages in Tort’ [1992] SydLawRw 23; (1992) 14(3) Sydney Law Review 340.

Peter Hanks, ‘Adjusting Medicare Benefits: Acquisition of Property?’ [1992] SydLawRw 34; (1992) 14(4) Sydney Law Review 495.

David Kell, ‘Representative Actions: Continued Evolution or a Classless Society?’ [1993] SydLawRw 41; (1993) 15(4) Sydney Law Review 527.

Dean Bell, ‘Admiralty Jurisdiction and the Constitution: The Shin Kobe Maru Case’ [1994] SydLawRw 6; (1994) 16(1) Sydney Law Review 97.

Penelope Pether, ‘True, Untrue or (Mis)represented? Section 410(1)(a) of the NSW Crimes Act’ [1994] SydLawRw 7; (1994) 16(1) Sydney Law Review 114.

Lee Aitken, ‘A Witness’s Civil Immunity from Criminal Prosecution’ [1994] SydLawRw 25; (1994) 16(3) Sydney Law Review 394.

Richard Naughton, ‘Revisiting the Contract of Employment — Byrne and Frew v Australian Airlines Limited’ [1995] SydLawRw 5; (1995) 17(1) Sydney Law Review 88.

Patrick Parkinson, ‘Fiduciary Law and Access to Medical Records: Breen v Williams’ [1995] SydLawRw 26; (1995) 17(3) Sydney Law Review 433.

Paul Ames Fairall, ‘Imprisonment without Conviction in New South Wales: Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions’ [1995] SydLawRw 36; (1995) 17(4) Sydney Law Review 573.

Reg Graycar and Jenny Morgan, ‘“Unnatural Rejection of Womanhood and Motherhood”: Pregnancy, Damages and the Law, A Note on CES v Superclinics (Aust) Pty Ltd’ [1996] SydLawRw 16; (1996) 18(3) Sydney Law Review 323.

Patricia Loughlan, ‘Music on Hold: The Case of Copyright and the Telephone: Telstra Corporation L td v Australasian Perfoming Rights Association Ltd’ [1996] SydLawRw 17; (1996) 18(3) Sydney Law Review 342.

Anne Twomey, ‘Dead Ducks and Endangered Political Communication — Levy v State of Victoria and Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation’ [1997] SydLawRw 4; (1997) 19(1) Sydney Law Review 76.

Ron McCallum, ‘Labour Law and the Inherent Requirements of the Job: Qantas Airlines Ltd v Christie — Destination: The High Court of Australia — Boarding at Gate Seven’ [1997] SydLawRw 11; (1997) 19(2) Sydney Law Review 211.

Anthony Duggan, ‘Till Debt Us Do Part: A Note on National Australia Bank Ltd v Garcia’ [1997] SydLawRw 12; (1997) 19(2) Sydney Law Review 220.

Jeremy Gans, ‘Why Would I Be Lying?: The High Court in Palmer v R Confronts an Argument That May Benefit Sexual Assault Complainants’ [1997] SydLawRw 29; (1997) 19(4) Sydney Law Review 568.

Nicholas Pengelley, ‘The Hindmarsh Island Bridge Act. Must Laws Based on the Race Power be for the “Benefit” of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders? And What Has Bridge Building Got To Do With the Race Power Anyway?’ [1998] SydLawRw 6; (1998) 20(1) Sydney Law Review 144.

Ben Kremer, ‘Copyright and Computer Programs: Data Access v Powerflex Before the High Court’ [1998] SydLawRw 12; (1998) 20(2) Sydney Law Review 296.

Mary Crock and Mark Gibian, ‘Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Eshetu’ [1998] SydLawRw 19; (1998) 20(3) Sydney Law Review 457.

Eilis S Magner, ‘HG v The Queen’ [1998] SydLawRw 26; (1998) 20(4) Sydney Law Review 599.

Eileen Webb and Diana Farrelly, ‘Campomar Sociedad Limitada & Anor v Nike International Ltd & Anor’ [1999] SydLawRw 11; (1999) 21(2) Sydney Law Review 278.

Suzanne B McNicol, ‘Esso Australia Resources Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation’ [1999] SydLawRw 25; (1999) 21(4) Sydney Law Review 656.

Barbara McDonald, ‘Immunities under Attack: The Tort Liability of Highway Authorities and their Immunity from Liability for Non-Feasance: Brodie v Singleton Shire Council, Ghantous v Hawkesbury City Council’ [2000] SydLawRw 19; (2000) 22(3) Sydney Law Review 411.

Michael Bryan and M P Ellinghaus, ‘Fault Lines in the Law Obligations: Roxborough v Rothmans of Pall Mall Australia Ltd’ [2000] SydLawRw 27; (2000) 22(4) Sydney Law Review 636.

Peter Handford, ‘When the Telephone Rings: Restating Negligence Liability for Psychiatric Illness; Tame v Morgan and Annetts v Australian Stations Pty Ltd’ [2001] SydLawRw 24; (2001) 23(4) Sydney Law Review 597.

Jeremy Gans, ‘The Case of the Improbable Murderer: De Gruchy v R’ (2002) 24(1) Sydney Law Review 123.

David Rolph, ‘The Message, Not the Medium: Defamation, Publication and the Internet in Dow Jones & Co v Gutnick’ (2002) 24(2) Sydney Law Review 263.

Sue McNicol, ‘Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Daniels Corporation International Pty Ltd and Another’ (2002) 24(2) Sydney Law Review 281.

Saul Fridman, ‘Sport and the Law: The South Sydney Appeal’ (2002) 24(4) Sydney Law Review 558.

Catherine Dauvergne and Jenni Millbank, ‘Applicants S396/2002 and S395/2002, A Gay Refugee Couple from Bangladesh’ [2003] SydLawRw 6; (2003) 25(1) Sydney Law Review 97.

Elisa Arcioni, ‘Politics, Police and Proportionality — An Opportunity to Explore the Lange Test: Coleman v Power’ [2003] SydLawRw 17; (2003) 25(3) Sydney Law Review 379.

Michael Handler, ‘The Panel Case and Television Broadcast Copyright’ [2003] SydLawRw 18; (2003) 25(3) Sydney Law Review 391.

Andrew Frazer, ‘Redundancy and Interpretation in Industrial Agreements: The Amcor Case’ [2004] SydLawRw 11; (2004) 26(2) Sydney Law Review 241.

Kimberlee Weatherall, ‘On Technology Locks and the Proper Scope of Digital Copyright Laws: Sony in the High Court’ [2004] SydLawRw 29; (2004) 26(4) Sydney Law Review 613.

Susan Kneebone, ‘Ruddock and Others v Taylor’ [2005] SydLawRw 6; (2005) 27(1) Sydney Law Review 143.

Lee Aitken, ‘“Litigation Lending” after Fostif: An Advance in Consumer Protection, or a Licence to “Bottomfeeders”?’ [2006] SydLawRw 8; (2006) 28(1) Sydney Law Review 171.

Maria O’Sullivan, ‘Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs v QAAH: Cessation of Refugee Status’ [2006] SydLawRw 17; (2006) 28(2) Sydney Law Review 359.

Daniel Guttman, ‘Vicki Roach v Commonwealth: Is the Blanket Disenfranchisement of Convicted Prisoners Unconstitutional?’ [2007] SydLawRw 11; (2007) 29(2) Sydney Law Review 297.

Emma Armson, ‘Attorney-General (Commonwealth) v Alinita Limited: Will the Takeovers Panel Survive Constitutional Challenge?’ [2007] SydLawRw 19; (2007) 29(3) Sydney Law Review 495.

Anthony Gray, ‘Getting it Right: Where is the Place of the Wrong in a Multinational Torts Case?’ [2008] SydLawRw 25; (2008) 30(3) Sydney Law Review 537.

David Hamer, ‘Mind the “Evidential Gap”: Causation and Proof in Amaca Pty Ltd v Ellis’ [2009] SydLawRw 18; (2009) 31(3) Sydney Law Review 465.

Jason Harris, ‘Charting the Limits of Insolvency Reorganisations: Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc v City of Swan’ [2010] SydLawRw 7; (2010) 32(1) Sydney Law Review 141.

Judith Bannister, ‘The Paradox of Public Disclosure: Hogan v Australian Crime Commission’ [2010] SydLawRw 8; (2010) 32(1) Sydney Law Review 159.

Jason Harris and Anil Hargovan, ‘Corporate Groups: The Intersection between Corporate and Tax Law; Commissioner of Taxation v BHP Billiton Finance Ltd’ [2010] SydLawRw 33; (2010) 32(4) Sydney Law Review 723.

Robert Burrell and Kimberlee Weatherall, ‘Providing Services to Copyright Infringers: Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Ltd’ [2011] SydLawRw 32; (2011) 33(4) Sydney Law Review 801.

Megan Richardson, ‘Why Policy Matters: Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’ [2012] SydLawRw 27; (2012) 34(3) Sydney Law Review 587.

Lauren Butterly, ‘Clear Choices in Murky Waters: Leo Akiba on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim Group v Commonwealth of Australia’ [2013] SydLawRw 9; (2013) 35(1) Sydney Law Review 237.

Anil Hargovan and Jason Harris, ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls: Directors’ Duties to Creditors after Bell’ [2013] SydLawRw 16; (2013) 35(2) Sydney Law Review 433.

Thalia Anthony, ‘Indigenising Sentencing? Bugmy v The Queen’ [2013] SydLawRw 17; (2013) 35(2) Sydney Law Review 451.

Matthew Groves, ‘Reviewing Reasons for Administrative Decisions: Wingfoot Australia Partners Pty Ltd v Kocak’ [2013] SydLawRw 25; (2013) 35(3) Sydney Law Review 627.

Jill Hunter, ‘Jury Deliberations and the Secrecy Rule: The Tail that Wags the Dog?’ [2013] SydLawRw 32; (2013) 35(4) Sydney Law Review 809.

Joellen Riley, ‘“Mutual Trust and Confidence” on Trial: At Last’ [2014] SydLawRw 6; (2014) 36(1) Sydney Law Review 151.

Gary Edmond and Mehera San Roque, ‘Honeysett v The Queen: Forensic Science, “Specialised Knowledge” and the Uniform Evidence Law’ [2014] SydLawRw 14; (2014) 36(2) Sydney Law Review 323.

Maria O’Sullivan, ‘Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v SZSCA: Should Asylum Seekers Modify their Conduct to Avoid Persecution?’ [2014] SydLawRw 23; (2014) 36(3) Sydney Law Review 541.

Brad Sherman, ‘D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc: Patenting Genes in Australia’ [2015] SydLawRw 6; (2015) 37(1) Sydney Law Review 135.

Anne Twomey, ‘McCloy v New South Wales: Developer Donations and Banning the Buying of Influence’ [2015] SydLawRw 13; (2015) 37(2) Sydney Law Review 275.

Rebecca Ananian Walsh and Kate Gover, ‘Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate: The End of Penalty Agreements in Civil Pecuniary Penalty Schemes?’ [2015] SydLawRw 19; (2015) 37(3) Sydney Law Review 417.

Katy Barnett, ‘Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd: Are Late Payment Fees on Credit Cards Enforceable?’ [2015] SydLawRw 27; (2015) 37(4) Sydney Law Review 595.

[∗] Editors, Sydney Law Review; Associate Professors, Faculty of Law, University of Sydney, Australia. We would like to thank all former SLR editors and BTHC authors, and Judge James Crawford, who provided us with information about the column. We would also like to thank Amelia Williams for excellent research assistance, Catrina Denvir for assistance with the statistics, Matthew Conaglen and David Rolph for comments on an earlier draft, Mary Crock for suggesting the title, and present and former Bond University Law School members Iain Field, Jim Corkery, Paul Fairall and Gerard Carney for assisting us in uncovering the history of the journal High Court Review.

[1] Michael Kirby, ‘Welcome to Law Reviews’ [2002] MelbULawRw 1; (2002) 26(1) Melbourne University Law Review 1, 8.

[2] Not all cases that formed the subject of BTHC columns proceeded to hearing, eg CES v Superclinics (Aust) Pty Ltd, addressed in Reg Graycar and Jenny Morgan, ‘“Unnatural Rejection of Womanhood and Motherhood”: Pregnancy, Damages and the Law, A Note on CES v Superclinics (Aust) Pty Ltd’ [1996] SydLawRw 16; (1996) 18(3) Sydney Law Review 323.

[3] Leonie Star, Julius Stone: An Intellectual Life (Oxford University Press and Sydney University Press, 1992) 118; John Mackinolty and Judy Mackinolty, A Century Downtown (Sydney University Law School, 1991) 118.

[4] Julius Stone, ‘A Note From the General Editor’ (1953–55) 1 Sydney Law Review 143.

[5] Frontispiece (1973–76) 7 Sydney Law Review vii; Editorial Committee, ‘Preface’ [1991] SydLawRw 1; (1991) 13(1) Sydney Law Review 5.

[6] See generally M Thornton, Privatising the Public University: The Case of Law (Routledge, 2011).

[7] Editorial Committee, ‘Preface’ [1991] SydLawRw 1; (1991) 13(1) Sydney Law Review 5.

[8] Thornton, above n 6, 62.

[9] Editorial Committee, above n 7.

[10] See Faculty of Law, University of Sydney, Sydney Law Review: Information for Students

(12 November 2015) <http://sydney.edu.au/law/slr/unit.shtml> .

[11] Ron McCallum and Wojciech Sadurski, who were Faculty of Law members in 1991 and subsequently editors of the SLR, attribute the idea for the BTHC column to James Crawford.

[12] James Crawford, correspondence with the authors, 27 September 2015.

[13] Editorial Committee, ‘Preface’ [1991] SydLawRw 1; (1991) 13 Sydney Law Review 5.

[14] Mason CJ, Deane and Gaudron JJ. A fourth, McHugh J, completed the NSW Law Society Legal Practice Admission Board program in which academic members of the Faculty of Law taught.

[15] James Crawford, correspondence with the authors, 27 September 2015.

[16] Geoffrey Lindell (ed), The Mason Papers: Selected Articles and Speeches by Sir Anthony Mason (Federation Press, 2007), ‘Legal Research: Its function and its importance’, 350.

[17] Ibid. Notably, Mason CJ was an author of the first judgment of the High Court to cite a BTHC column (Peter Hanks, ‘Adjusting Medicare Benefits: Acquisition of Property?’ [1992] SydLawRw 34; (1992) 14(4) Sydney Law Review 495 in Health Insurance Commission v Peverill [1994] HCA 8; (1994) 179 CLR 226, 237), but did not cite any further BTHC columns for the remainder of his term. In the speech at the University of Melbourne, Mason also referred to a journal published by Bond Law School called Amicus Curiae designed to have the same purpose as the BTHC column. This was the original title of the journal High Court Review published by Bond Law School 1995–2000, which is discussed further below. Paul Fairall, who was integral to the establishment of the High Court Review, recalls that the Journal had the strong backing of Mason CJ (correspondence with the authors, held on file by the authors).

[18] See generally Neil Duxbury Jurists and Judges: An Essay on Influence (Hart Publishing, 2001).

[19] Correspondence between former SLR editors and the authors, held on file by the authors.

[20] One former editor recalled the necessity of having to ‘decommission’ a potential BTHC column because it appeared that the judgment itself was going to be published before the column!

[21] The High Court Review provided commentary on appellate court decisions and cases under appeal to the High Court. It lasted for 6 volumes from 1995 to 2000 and published 19 commentaries in total (ranging in frequency from 1 in 1999 to 7 in 1996). Interestingly, the difficulty of commissioning and publishing articles before the relevant High Court hearing was held was also mentioned by Gerard Carney and Paul Fairall, former editors of the High Court Review, with respect to their time editing that journal: correspondence between Gerard Carney, Paul Fairall and the authors, held on file by the authors.

[22] See Melbourne Law School, Opinions on High: High Court Blog <http://blogs.unimelb.edu.au/

opinionsonhigh/>.

[23] Andrew Stewart, ‘Industrial Disputes and the Prevention Power: The World Square Case’ [1991] SydLawRw 15; (1991) 13(2) Sydney Law Review 199.

[25] Graeme Cooper, ‘The Treatment of Demolition Expenses under the Income Tax: The Mount Isa Mines Case’ [1991] SydLawRw 33; (1991) 13(4) Sydney Law Review 605.

[27] Mount Isa Mines Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1992] HCA 62; (1992) 176 CLR 141, 143.

[28] [1994] HCA 8; (1994) 179 CLR 226.

[29] Peter Hanks, ‘Adjusting Medicare Benefits: Acquisition of Property?’ [1992] SydLawRw 34; (1992) 14(4) Sydney Law Review 495.

[30] [1994] HCA 8; (1994) 179 CLR 226, 237.

[31] [2015] HCA 35 (7 October 2015) [136].

[32] Brad Sherman, ‘D’Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc: Patenting Genes in Australia’ [2015] SydLawRw 6; (2015) 37(1) Sydney Law Review 135.

[33] The column by Graeme Cooper was mentioned in the headnote, Graeme Cooper, ‘The Treatment of Demolition Expenses under the Income Tax: The Mount Isa Mines Case’ [1991] SydLawRw 33; (1991) 13(4) Sydney Law Review 605 (Mount Isa Mines Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1992] HCA 62; (1992) 176 CLR 141, 143). Columns by Anthony Duggan and Jeremy Gans were mentioned both in the headnote, and cited in the relevant decisions: Anthony Duggan, ‘Till Debt Us Do Part: A Note on National Australia Bank Ltd v Garcia’ [1997] SydLawRw 12; (1997) 19(2) Sydney Law Review 220 (Garcia v National Australia Bank Ltd [1998] HCA 48; (1998) 194 CLR 395, 398, 426, 429); Jeremy Gans, ‘Why Would I be Lying?: The High Court in Palmer v R Confronts an Argument That May Benefit Sexual Assault Complainants’ [1997] SydLawRw 29; (1997) 19(4) Sydney Law Review 568 (Palmer v The Queen [1998] HCA 2; (1998) 193 CLR 1, 2, 37).

[34] Gans, above n 33 (cited in De Gruchy v The Queen [2002] HCA 33; (2002) 211 CLR 85, 100, 104); Peter Handford, ‘When the Telephone Rings: Restating Negligence Liability for Psychiatric Illness; Tame v Morgan and Annetts v Australian Stations Pty Ltd’ [2001] SydLawRw 24; (2001) 23(4) Sydney Law Review 597 (cited in Graham Barclay Oysters v Ryan [2002] HCA 54; (2002) 211 CLR 540, 626).

[35] Catherine Dauvergne and Jenni Millbank, ‘Applicants S396/2002 and S395/2002, A Gay Refugee Couple from Bangladesh’ [2003] SydLawRw 6; (2003) 25(1) Sydney Law Review 97 (cited in Application NABD of 2002 v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2005] HCA 29; (2005) 216 ALR 1, 30).

[36] Russell Smyth, ‘Academic Writing and the Courts: A Quantitative Study of the Influence of Legal and Non-Legal Periodicals in the High Court [1998] UTasLawRw 12; (1998) 17(2) University of Tasmania Law Review 164.

[37] Judges’ associates have a key role to play here. For discussion, see ibid.

[38] Excluding the five columns where the High Court proceedings were discontinued, and the two columns for which no judgment had been delivered at the time of writing.

[39] Barbara McDonald, ‘Immunities under Attack: The Tort Liability of Highway Authorities and their Immunity from Liability for Non-Feasance: Brodie v Singleton Shire Council, Ghantous v Hawkesbury City Council’ [2000] SydLawRw 19; (2000) 22(3) Sydney Law Review 411.

[40] [2001] HCA 29; (2001) 206 CLR 512.

[41] Kirby, above n 1.

[42] Ibid 8.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Michael Handler, ‘The Panel Case and Television Broadcast Copyright’ [2003] SydLawRw 18; (2003) 25(3) Sydney Law Review 391.

[45] [2004] HCA 14; (2004) 218 CLR 273.

[46] Lionel Bently and Brad Sherman, Intellectual Property Law (Oxford University Press, 4th ed, 2014) 208 (n 113).

[47] Kimberlee Weatherall, ‘On Technology Locks and the Proper Scope of Digital Copyright Laws: Sony in the High Court’ [2004] SydLawRw 29; (2004) 26(4) Sydney Law Review 613.

[48] [2005] HCA 58; (2005) 224 CLR 193.

[49] David Brennan, ‘What Can It Mean “To Prevent or Inhibit the Infringement of Copyright”? —

A Critique on Stevens v Sony’ (2006) 17(1) Australian Intellectual Property Journal 81, 84–5.

[50] Discussed in Duxbury above n 18, 78–9.

[51] Smyth, above n 36, 171; see also Russell Smyth ‘Other Than “Accepted Sources of Law”:

A Quantitative Study of Secondary Source Citations in the High Court’ [1999] UNSWLawJl 40; (1999) 22(1) UNSW Law Journal 19.

[52] Ibid. While we did not make a specific finding about dissenting judgments, the profile of Kirby J in our findings dovetails with what other research has found — that dissenting judges cite more academic authorities than majority judgments: see ibid, 177 (suggesting this is perhaps because dissenting judgments reflect novel legal analysis).

[53] See Kirby, above n 1, Robert French, ‘The Chief Justice and the Governor-General’ [2009] MelbULawRw 23; (2009) 33(3) Melbourne University Law Review 647, and J Gava, ‘Law Reviews: Good for Judges, Bad for Law Schools?’ [2002] MelbULawRw 29; (2002) 26(3) Melbourne University Law Review 560.

[54] See, eg, Robert French, ‘The Chief Justice and the Governor-General’ [2009] MelbULawRw 23; (2009) 33(3) Melbourne University Law Review 647, 648. See also Robert French, ‘Judges and Academia — Building Bridges’ [2007] Federal Judicial Scholarship 12 [7]; Kirby, above n 1.

[55] Although, as noted above, at least three BTHC columns have been cited by the High Court in later judgments.

[56] Joellen Riley, ‘“Mutual Trust and Confidence” on Trial: At Last’ [2014] SydLawRw 6; (2014) 36(1) Sydney Law Review 151.

[57] [2014] HCA 32; (2014) 253 CLR 169.

[58] Ruddock v Taylor (2005) 222 CLR 612.

[59] Susan Kneebone, ‘Ruddock and Others v Taylor’ [2005] SydLawRw 6; (2005) 27(1) Sydney Law Review 143.

[60] Ibid.

[61] [2013] HCA 43; (2013) 252 CLR 480.

[62] Matthew Groves, ‘Reviewing Reasons for Administrative Decisions: Wingfoot Australia Partners Pty Ltd v Kocak’ [2013] SydLawRw 25; (2013) 35(3) Sydney Law Review 627.

[63] [2013] HCA 43; (2013) 252 CLR 480, 498 [45] (‘Wingfoot v Kocak’).

[64] Kirby, above n 1, 8.

[65] Lauren Butterly, ‘Clear Choices in Murky Waters: Leo Akiba on behalf of the Torres Strait Regional Seas Claim Group v Commonwealth of Australia’ [2013] SydLawRw 9; (2013) 35(1) Sydney Law Review 237.

[67] Butterly, above n 65, 249–50.

[68] This includes 10 BTHC columns that were co-authored by two authors, seven authors who have contributed two BTHC columns, and one author who has contributed three BTHC columns (twice as a co-author, and once as a sole author).

[69] We did not contact three BTHC authors where the relevant High Court proceedings were still continuing at the time we undertook this research.

[70] The potential impact of those columns written by the remaining 41% of authors who did not respond to our email is unknown, although it may be safe to assume that the percentage of those BTHC columns that have not been further cited is higher than in the responding group — as the absence of ‘positive’ information to convey may have led to a higher non-response rate.

[71] Anne Twomey, ‘Dead Ducks and Endangered Political Communication — Levy v State of Victoria and Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation’ [1997] SydLawRw 4; (1997) 19(1) Sydney Law Review 76.

[72] [1997] HCA 31; (1997) 189 CLR 579.

[73] [1997] HCA 25; (1997) 189 CLR 520.

[74] Levy v State of Victoria [1997] HCA 31; (1997) 189 CLR 579, 632, 642.

[75] [2004] INSC 43 (23 January 2004).

[76] Catherine Dauvergne and Jenni Millbank, ‘Applicants S396/2002 and S395/2002, A Gay Refugee Couple from Bangladesh’ [2003] SydLawRw 6; (2003) 25(1) Sydney Law Review 97.

[77] [2011] UKUT 251 (24 June 2011), [76].

[78] Patrick Parkinson, ‘Fiduciary Law and Access to Medical Records: Breen v Williams’ [1995] SydLawRw 26; (1995) 17(3) Sydney Law Review 433 cited in Paramasivan v Flynn [1998] FCA 1711; (1998) 90 FCR 489.

[79] Gans, above n 33, cited in R v Reid [2006] QCA 202; [2007] 1 Qd R 64.

[80] Gary Edmond and Mehera San Roque, ‘Honeysett v The Queen: Forensic Science, “Specialised Knowledge” and the Uniform Evidence Law’, [2014] SydLawRw 14; (2014) 36(2) Sydney Law Review 323 cited in Tuite v The Queen [2015] VSCA 148 (12 June 2015).

[81] Megan Richardson, ‘Why Policy Matters: Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’ [2012] SydLawRw 27; (2012) 34(3) Sydney Law Review 587.

[82] (2013) 249 CLR 435.

[83] Robert Burrell and Kimberlee Weatherall, ‘Providing Services to Copyright Infringers: Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v iiNet Ltd’ [2011] SydLawRw 32; (2011) 33(4) Sydney Law Review 801.

[84] [2012] HCA 16; (2012) 248 CLR 42.

[85] Richardson, above n 81, 587–8.

[86] Gans, above n 33.

[87] [1998] HCA 2; (1998) 193 CLR 1.

[88] Victorian Law Reform Commission, Jury Directions, Consultation Paper (2008) 41–2.

[89] Butterly, above n 65.

[90] Australian Law Reform Commission, Connection to Country: Review of the Native Title Act, Final Report (Commonwealth of Australia, 2015) 235.

[91] Jeremy Gans, ‘The Case of the Improbable Murderer: De Gruchy v R’ (2002) 24(1) Sydney Law Review 123.

[92] [2002] HCA 33; (2002) 211 CLR 85.

[93] Legal Information Access Centre, LIAC Crime Library: A Collection of well-known criminal cases designed as a resource for HSC Legal Studies Students (State Library of NSW, 2010) 29.

[94] See R Smyth, ‘Citing Outside the Law Reports: Citations of Secondary Authorities on the Australian State Supreme Courts Over the Twentieth Century’ (2009) 18(3) Griffith Law Review 692, 720–21.

[95] ‘Impact’ measures are more popular in research assessment exercises outside Australia, but seem likely to be adopted here. Re ‘impact’ measures, see British Academy, Peer Review: The Challenges for the Humanities and Social Sciences (London, 2007), ch 6, <http://www.britac.ac.uk/

policy/peer-review.cfm>.

[96] All Sydney Law Review content (including Before the High Court columns) is available online at <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/SydLawRw/> .

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/SydLawRw/2015/26.html