Sydney Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Sydney Law Review |

|

Who is Diverted?: Moving beyond Diagnosed Impairment towards a Social and Political Analysis of Diversion

Linda Steele,[∗] Leanne Dowse[†] and Julian Trofimovs[‡]

Abstract

Diversion from the criminal justice system pursuant to s 32 of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW) is increasingly being deployed as a key response to the issues facing people diagnosed with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness in the criminal justice system. The ‘medical model’ of disability, which is focused on disability as an internal, individual pathology, contributes to the marginalisation of people with disability, notably by providing a legitimate basis for the legal and social regulation of people with disability through therapeutic interventions. The scholarly field of critical disability studies contests the medical model by making apparent the social and political contingency of disability, including the intersection of disability with other dimensions of politicised identity (such as gender and Indigeneity) and the role of law and institutions (including the criminal justice system) in the disablement, marginalisation and criminalisation of people with disability. Applying critical disability studies to s 32 problematises the characterisation of the legal subject with diagnosed impairment and this provides a new basis for questioning the coercion of people with disability through the criminal justice intervention of diversion. An empirical analysis of the diagnostics, demographics and criminal justice pathways of a sample of individuals who have received s 32 orders provides some material foundations for a more politically and socially directed analysis of s 32 and for a broader reflection on the role of the criminal law in issues facing people diagnosed with cognitive impairments and mental illness in the criminal justice system.

Diversion from the criminal justice system pursuant to s 32 of the Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 (NSW) (‘MHFP Act’) is increasingly being deployed as a key response to the issues facing people diagnosed with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness in the criminal justice system. Pursuant to s 32, individuals diagnosed with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness appearing in the New South Wales (‘NSW’) Local Court and NSW Children’s Court can have their charges dismissed prior to conviction, generally conditional on compliance with a six-month court order requiring engagement with disability services and mental health treatment.

Law reform organisations, legal professionals, disability advocacy organisations and criminal justice and forensic mental health and disability service providers[1] and a relatively small body of legal scholarship support s 32 on the basis that it is humane and therapeutic.[2] Section 32 is considered humane because it moves an individual with cognitive impairment or mental illness away from exposure to the negative effects of the court process and imprisonment and to disability and mental health community support services that will enhance the individual’s ability to live in the community. Section 32 is viewed as therapeutic in providing a pathway to disability and mental health services that are presumed to address the offending behaviour assumed to be intrinsic to the impairments of individuals with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness. As well as its characterisation as humane and therapeutic, s 32 is increasingly recognised as a significant component of the criminal law’s role in addressing the issues facing individuals with disability in the criminal justice system. This is most evident in the recent NSW Law Reform Commission (‘NSWLRC’) review of people with cognitive and mental health impairments in the criminal justice system, which devotes an entire consultation paper and final report to diversion.[3]

Despite its growing popularity, s 32 remains largely immune from scholarly analysis directed towards questioning its social and political contexts, and analysis of its underlying assumptions and systemic effects.[4] Instead, commentary is concentrated on fine-tuning the legal framework, increasing the number of orders made and enhancing the effectiveness of compliance with s 32 orders. Of particular significance is the absence of scholarly analysis of s 32’s coercive effects. Section 32 has coercive effects because diversion into disability services and mental health treatment is legally effected by a court order pursuant to which an individual must engage with the specified services and/or treatment. A failure to comply with the order brings that individual back to court to have his or her original charges determined. The coercive effects of s 32 orders apply only to people with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness (who, moreover, have not been convicted of any criminal offences).[5] These complex issues in s 32 around coercion, disability and criminal law are yet to be fully considered in legal scholarship.

Critical disability studies scholarship provides new possibilities for analysing coercion of people with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness through s 32. It contests the ‘medical model’ focus on disability as internal, individual pathology, and makes apparent the social and political contingency of disability, including the intersection of disability with other dimensions of politicised identity (such as gender and Indigeneity) and the complex role of law and institutions (including the criminal justice system) in the disablement, marginalisation and criminalisation of people with disability.

A critical disability studies lens reveals the figure of the legal subject with diagnosed impairment as central to s 32 — that is, in order for an individual to be subject to s 32’s jurisdiction, the individual must be ‘developmentally disabled’, ‘suffering from mental illness’ or ‘suffering from a mental condition for which treatment is available in a mental health facility’.[6] It is this legal subject that then grounds the use of therapeutic interventions targeted at the diagnosed impairment in s 32 orders. Thus, one approach to contest the coercive effects of s 32, is to problematise the core figure of the legal subject with diagnosed impairment. This article does this by making apparent the social and political dimensions of the embodied individuals who receive s 32 orders, specifically by developing knowledge on their identities beyond diagnosed impairment and their criminal justice pathways beyond the s 32 order. The article draws on a study of 149 individuals with diagnosed cognitive impairment and/or mental illness who have been in custody in a NSW prison and have received a s 32 order at some point in their lives (‘the s 32 subjects’). The findings paint a detailed picture of individuals characterised by complex diagnostic, demographic and criminal justice dimensions not previously articulated. This unsettles the idea of diagnosed impairment as both a way to characterise these individuals as legal subjects and, in turn, as an appropriate basis for legitimising the coercive intervention in their lives that occur through s 32 orders. These findings will have relevance to other jurisdictions both in Australia and internationally, in light of the growing popularity of diversion.[7]

The article calls into question the appropriateness of s 32 as a mechanism for addressing the systemic issues for individuals diagnosed with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness in the criminal justice system. We urge scholars, law reformers and disability rights advocates to ask deeper questions about the use of diagnosed impairment as a legal category, the capacity of criminal law to acknowledge its own marginalising effects and ultimately the appropriateness of therapeutic interventions through criminal law.

Part II provides an overview of the legal framework of s 32 and identifies its coercive effects. Part III then introduces and draws on critical disability studies to establish the centrality to s 32 of the legal subject with diagnosed impairment and the basis for problematising diagnosed impairment through making apparent the social and political dimensions of the embodied individuals who receive s 32 orders. Part IV outlines the study methodology and the approach to empirical analysis. Parts V–VIII examine the findings of the empirical analysis on the complex nature of diagnosed impairment for s 32 subjects, the compounding effects of other politicised aspects of identity including gender and Indigeneity, and social disadvantage and trends in the criminal justice pathways of the s 32 subjects. The article concludes in Part IX by identifying some of the ways in which this more nuanced picture of individuals who are subject to s 32 orders calls into question its coercive effects and provides some material foundations for a more politically and socially directed analysis of s 32. The article ultimately calls for a broader reflection on the role of criminal law in the issues facing people diagnosed with cognitive impairments and/or mental illness in the criminal justice system.

Pursuant to s 32 of the MHFP Act, a defendant diagnosed with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness appearing in the NSW Local Court or the NSW Children’s Court can be made subject to a court order that provides for the dismissal of that defendant’s criminal charges.[8] A s 32 application can be made at any time during the Local Court proceedings concerning the defendant’s charges.[9] An application is generally made by way of an oral application by the defence in the course of the proceedings. It is typically accompanied by two documents: (i) a psychological, psychiatric or neuropsychological report detailing the defendant’s diagnosis; and (ii) a ‘treatment plan’ or ‘case plan’ by a disability or mental health service outlining the treatment and services that the defendant could access under a conditional s 32 order.[10]

A magistrate can make a s 32 order following a threestage inquiry (the ‘El Mawas inquiry’) based on ss 32(1)–(3) of the MHFP Act and laid out in the NSW Court of Appeal decision of Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW) v El Mawas.[11] The first stage of the inquiry is whether the defendant is ‘developmentally disabled’, ‘suffering from mental illness’ or ‘suffering from a mental condition for which treatment is available in a mental health facility’.[12] The first stage was characterised by McColl JA as the ‘jurisdictional question’ of s 32 because the court’s jurisdiction or authority to deal with an individual pursuant to this provision is dependent upon the finding of fact of the impairment in relation to that individual.[13]

The second stage of the inquiry is whether it is ‘more appropriate’ for the defendant to be dealt with by s 32 ‘than otherwise in accordance with law’.[14] While the first stage of the El Mawas inquiry is the observation of a ‘fact’, the second stage is a discretionary judgement involving the consideration of a number of factors.[15]

The third stage of the El Mawas inquiry is whether an appropriate s 32 order can be made.[16] At this stage, the magistrate considers whether an unconditional or conditional order is appropriate, and whether there are the necessary services and treatment available to make any conditional order contemplated. Overall, the magistrate balances

the public interest in those charged with a criminal offence facing the full weight of the law against the public interest in treating, or regulating to the greatest extent practical, the conduct of individuals suffering from [the relevant impairment] with the object of ensuring that the community is protected from the conduct of such persons.[17]

If appropriate in light of the El Mawas inquiry, the magistrate can make:

a s 32 order[18] dismissing the defendant’s charges either unconditionally;[19] a six-month conditional s 32 order;[20] or an interim s 32 order that places conditions on a defendant for a period prior to determination of the charges.[21] A conditional s 32 order pursuant to s 32(3) involves dismissal of an individual’s charges and discharge from the court process, coupled with the individual either being put into the care of a responsible person or being required to be assessed or treated. This generally involves being discharged into the care of a case manager or treating mental health professional specified in the treatment or support plan submitted by the defence; and/or having to comply with all reasonable directions made by that case manager or treating mental health professional. Individuals might also be discharged conditional on attending appointments for assessment and treatment. There is a period of six months after the making of a conditional s 32 order during which service providers can report a breach of a conditional s 32 order.[22]

A defendant can be called back before the court and, if the breach is made out, possibly have their charges heard afresh.[23]

While diversion into disability services and mental health treatment in s 32 is typically framed as humane and beneficial compared with prison, the legal framework of s 32 demonstrates the coercive effects of conditional s 32 orders. Diversion is legally effected by a court order pursuant to which an individual must engage with the specified services and/or treatment because a failure to do so brings that individual back to court to have his or her original charges determined. Moreover, the coercive effects of s 32 orders apply only to people with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness by reason of the jurisdictional question of s 32, coupled with the particular disability-related factors relevant to the appropriateness of an order (at the second stage of the El Mawas inquiry) and the use of disability services and mental health treatment in conditional s 32 orders.[24]

Critical disability studies scholarship provides new possibilities for contesting the coercion of people with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness through s 32 by problematising the medicalisation of disability and the regulative possibilities associated with medicalisation. As Devlin and Pothier suggest: ‘disability is not fundamentally a question of medicine or health, nor is it just an issue of sensitivity and compassion; rather, it is a question of politics and power(lessness)’.[25] Critical disability studies scholarship questions a focus on individual pathology. Instead, it draws attention to the marginalisation of people with disability and questions the function of diagnostic categorisation as a legitimate basis for the legal and social regulation of people with disability, including through therapeutic interventions and the use of disability services to structure life choices.[26] This approach makes apparent the social and political contingency of disability, including the intersection of disability with other dimensions of politicised identity (such as gender and Indigeneity);[27] the relationship of the emergence of impairment to historical and geopolitical dimensions of power and inequality;[28] and the complex role of law and institutions (including the criminal justice system) in the disablement and criminalisation of people with disability.[29]

Critical disability scholars have argued that diagnosed impairment can be analysed as ‘disciplinary’.[30] This is because diagnostic definitions of impairment provide norms of behaviour and functioning against which individuals are measured. This measurement is not merely for the purpose of a retrospective and static description. Rather, it provides a basis for intervention in order to remedy or manage the individuals’ deviations from the norms. Intervention is framed in humane, therapeutic and empowering terms, angled toward achieving integration with predetermined social norms.[31] Coupled with this, critical disability studies scholars have recognised the regulative nature of disability services and mental health treatment in a post-deinstitutionalisation context,[32] as well as the way in which legal orders can harness these to enable regulation of people with disability.[33]

Critical disability studies scholarship provides new possibilities for challenging the coercion of people with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness through s 32 for two main reasons. First, it illuminates the centrality to s 32 of an understanding of cognitive impairment and mental illness as diagnosed impairment and its characterisation of the s 32 subjects as legal subjects so diagnosed. Second, it provides a way to contest diagnosed impairment and its use in s 32 for regulative ends by directing analytical attention to the social and political contingency of disability in individuals who receive s 32 orders.

Central to s 32 is the figure of the legal subject with diagnosed impairment. First, in relation to the legislative framework of s 32, diagnosed impairment is at every stage of the El Mawas inquiry. The ‘jurisdictional question’ of s 32 — the legal gateway to an individual being considered for a s 32 order — is that the individual has a ‘diagnosed impairment’. This entails a scientific, value-neutral approach prioritising internal psychological processes (for example, ‘learning’ and ‘comprehension’) and their connection to diagnostic labels (for example, ‘intellectual disability’) attributed to individuals following an expert process of diagnosis. Importantly, the individual is not someone with disability among other features, but instead is negatively defined as an individual who is ‘developmentally disabled’, ‘suffering from mental illness’ or ‘suffering from a mental condition’.[34] Diagnosed impairment becomes a (legal) ‘synecdoche’[35] for the individual, a ‘contamination of identity’, whereby an individual’s condition is ‘understood to be embedded in the very fabric of their physical and moral [or, in this case, legal] personhood’.[36]

The second and third stages of the El Mawas inquiry similarly focus on diagnosed impairment. In the second stage, the court considers the implications of the diagnosed impairment for the most appropriate mainstream and diversionary criminal justice system option. At the third stage, the court considers the impairment in order to determine the disability service and mental health treatment interventions that will treat or regulate the impairment. Here, the documents submitted by the defence in support of the s 32 application are central to this characterisation insofar as they are produced by mental health and disability professionals and are focused on diagnosis itself and the appropriately matched treatment and services. The conditional s 32 orders themselves utilise disability services and mental health treatment to structure individuals’ lives in a manner that limits their choices and spatial location, and modifies their mood, physical activity and behaviour.[37] As we have argued here, the critical disability studies paradigm contests the self-evident nature of this medicalisation and the regulation it permits.

This article now turns to an empirical investigation of a sample of individuals subject to s 32 in NSW. In presenting this data, we consider how diagnosed impairment in s 32 might be problematised by shifting away from how law represents those it acts upon, to making apparent the social and political dimensions of the embodied individuals who receive s 32 orders.

To date, the small body of empirical research on individuals who receive s 32 orders has been principally quantitative in nature and focused on s 32 use, with some quantification by reference to diagnosis.[38] This offers limited insights[39] and forecloses broader social and political analysis by focusing only on individuals’ diagnosed impairment at the moment of the order, ignoring their longitudinal criminal justice involvement and the possibly harmful and criminalising effects of the criminal justice system itself. Together with its focus on the counting of orders, research presenting the empirical ‘realities’ of individuals who receive s 32 orders serves to confirm the need for s 32 and for criminal law intervention by the state in the lives of people diagnosed with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness. In order to problematise this characterisation of individuals by reference to diagnosed impairment and expose the centrality of this to s 32’s coercive effects, the following section presents an empirical examination of a sample of individuals who received s 32 orders under the MHFP Act.

The empirical approach utilised in the study reported here[40] involves quantitative analysis of data related to the use of s 32 orders for 149 individuals diagnosed with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness who have come before the Children’s and Local Courts in NSW as a result of an offence at any time preceding the draw of the data. There is no data available on the use of s 32 orders specifically in relation to individuals who have never been in custody, so the sample is purposive, rather than being representative of all individuals who receive s 32 orders.

The data describes the sample’s demographic characteristics and longitudinal human service and criminal justice pathways. The sample is derived from a larger cohort of 2731 men and women,[41] both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, who have been in prison in NSW and whose cognitive impairment and/or mental illness diagnosis is known. The quantitative analysis examines aspects of identity including Indigeneity, gender and age; as well as criminal justice involvement over time in order to provide a nuanced account of the operation of diagnosed impairment and its intersections with social disadvantage and criminal justice pathways for individuals who are the subject of s 32.

There are five study groups for the purposes of analysis, delineated on the basis of diagnosis. These are:

(i) Intellectual Disability (‘ID’): Individuals with an Intellectual Disability diagnosis only (defined here as IQ < 70) and no Mental Health Disorder (‘MHD’) diagnosis.

(ii) Borderline Intellectual Disability (‘BID’): Individuals with a Borderline Intellectual Disability diagnosis only (defined here as IQ =70–80) and no Mental Health Disorder diagnosis.

(iii) Mental Health Disorder (‘MHD’): Individuals with a Mental Health Disorder diagnosis only and no Intellectual Disability or Borderline Intellectual Disability diagnosis. Mental Health Disorder is defined here as having been diagnosed with any anxiety disorder, affective disorder, psychosis, personality disorder or substance use disorder in the previous 12 months.

(iv) Mental Health Disorder and Intellectual Disability (‘MHD_ID’): Individuals with a Mental Health Disorder diagnosis and an Intellectual Disability diagnosis.

(v) Mental Health Disorder and Borderline Intellectual Disability (‘MHD_BID’): Individuals with a Mental Health Disorder diagnosis and a Borderline Intellectual Disability diagnosis.

Data on the life-long human services and criminal justice involvement of each individual was drawn from a linked dataset[42] merging existing administrative records from NSW criminal justice and human service agencies: Police, Corrections, Justice Health, Courts, Juvenile Justice, Legal Aid, Disability, Housing, Health and Community Services. The dataset allows detailed pathway analysis of the ways people who are diagnosed with Cognitive Disability (‘CD’; those with ID or BID) and Mental Health Disorder enter, move through, exit and return to the criminal justice system and an understanding of the interactions between the justice and human service agencies affecting them. De-identified data was drawn on the sample’s demographic characteristics, criminal justice contacts, social and health factors, disability service usage, and s 32 orders.

Quantitative statistical analysis was undertaken to give an aggregate picture of the sample, with comparative analysis of study groups, including single and multiple diagnosis groups, including those with Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder and according to gender and Indigenous status. The data was analysed in this way in order to examine the multiplicity of diagnosed impairment, the complex interrelationships between diagnosed impairment and demographics, and the relationships between diagnosed impairment, disadvantage, institutional interventions, criminalisation and victimisation.

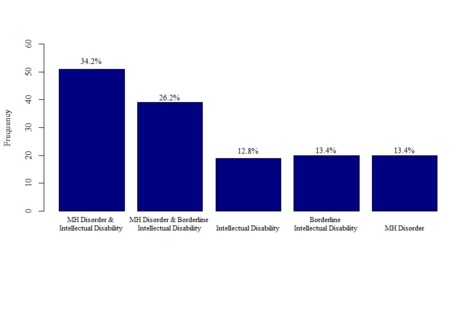

To critique diagnosed impairment in s 32, a more nuanced picture of the s 32 subjects begins with diagnoses. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the study sample according to diagnostic category.

Figure 1: Section 32 subjects’ data diagnostic category breakdown: raw count and percentages

Figure 1 shows that 87% of the s 32 subjects had a Cognitive Disability diagnosis, and 74% had a diagnosis of Mental Health Disorder (noting that many are diagnosed with both). This higher proportion of s 32 subjects with the diagnosis of Cognitive Disability, as compared to those with a diagnosis of Mental Health Disorder suggests that cognitive impairment, far from being of only marginal significance to s 32 (particularly as compared to mental illness)[43] is, at least for this group, at the core of the provision’s operation.

Figure 1 shows the significance of ‘marginal’ cognitive impairment diagnosis to the sample. Cognitive impairment is most generally associated in psychological and disability literature with ‘intellectual disability’, whereas the diagnostic category of borderline intellectual disability sits at the margins of what is contemplated by this category. In the context of s 32, ‘intellectual disability’ is generally equated with the legislative category of ‘developmental disability’[44] and, hence, as the diagnostic category that is typically associated with s 32’s application to individuals with cognitive impairment. Consequently, borderline intellectual disability sits ambiguously and uneasily at the edges of the provision’s operation.[45] Of the s 32 subjects in this sample with Cognitive Disability, 40% have Borderline Intellectual Disability. While individuals with borderline intellectual disability receive s 32 orders, this diagnosis is not expressly included in the diagnostic categories specified in s 32(1) of the MHFP Act.

Figure 1 also shows diagnostic complexity by the high proportion of s 32 subjects with a complex diagnosis of Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder (60%), rather than a single diagnosis of Cognitive Disability (26%) or a single diagnosis of Mental Health Disorder (13%). This feature is significant given that diagnostic categorisation in s 32(1) does not explicitly acknowledge complex diagnosis. This evidence complicates the idea of distinct categories of individuals characterised by reference to mental illness or cognitive impairment (or, in the words of s 32 itself, of the individual who is ‘developmentally disabled’, ‘suffering from mental illness’ or ‘suffering from a mental condition’[46]). Instead, it is evident that s 32 subjects are diagnostically complex, a fact that remains unacknowledged in the currently bounded diagnostic categories used in s 32.

The possibility that the s 32 subjects are anything other than impaired is not fully explored in the academic research on s 32 and is noted only in passing by the advocacy and law reform discussion of s 32.[47] Motivated by the critical disability studies scholarship that illuminates the significance of intersectionality to the identity and experiences of people with disability,[48] this part focuses on gender and Indigeneity and the interrelationships between these characteristics and Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder. Examination of other dimensions of politicised identity that might also be significant (including refugee status, sexuality, cultural and linguistic diversity and other dimensions of race such as ‘whiteness’) is beyond the scope of the available data.

Table 1 sets out the demographic characteristics of the s 32 subjects.

Table 1: Section 32 subjects’ demographics: raw count and percentage totals*

|

Demographics

|

ID

|

BID

|

MHD

|

MHD_ID

|

MHD_BID

|

Total

|

|||

|

Gender

|

Male (‘M’)

|

19

|

19

|

17

|

41

|

36

|

132

(88.6%)

|

||

|

Female (‘F’)

|

0

|

1

|

3

|

10

|

3

|

17

(11.4%)

|

|||

|

Indigenous

|

Indigenous

|

4

|

6

|

2

|

16

|

14

|

42

(28.2%)

|

||

|

Non-Indigenous

|

15

|

14

|

18

|

35

|

25

|

107

(71.2%)

|

|||

|

Indigenous - Gender

|

Indigenous

|

M

|

4

|

5

|

2

|

13

|

13

|

37

(24.8%)

|

|

|

F

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

3

|

1

|

5

(3.4%)

|

|||

|

Non- Indigenous

|

M

|

15

|

14

|

15

|

28

|

23

|

95

(63.8%)

|

||

|

F

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

7

|

2

|

12

(8.1%)

|

|||

* Key to diagnoses: ID = Intellectual Disability; BID = Borderline Intellectual Disability;

MHD = Mental Health; MHD_ID = Mental Health and Intellectual Disability;

MHD_BID = Mental Health and Borderline Intellectual Disability.

Table 1 indicates significant intersection between dimensions of gender and Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder in relation to the s 32 subjects, with the sample being overwhelmingly male (88.6%; 132 of 149). While it is not possible to draw conclusions about women from the small sample (n=17), it can be noted that diagnostic complexity is a hallmark of this group, with 13 of the 17 women represented in the sample having complex diagnoses of Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder.

Just over 28% of the s 32 subjects in the sample are Indigenous Australians (42 of 149). Almost all these individuals have a diagnosis of Cognitive Disability, with only 2 of the 42 having a single diagnosis of Mental Health Disorder. Nearly 75% of this group (30 of 42) have a complex diagnosis: 16 of 42 have Mental Health and Intellectual Disability and a further 14 of 42 have Mental Health and Borderline Intellectual Disability.

In relation to the intersection of Indigeneity and gender, male Indigenous Australians make up almost 25% of the total sample (37 of 149), with over half of these having complex diagnoses (26 of 37 made up of 13 of 37 having Mental Health and Intellectual Disability and 13 of 37 have Mental Health and Borderline Intellectual Disability). Indigenous Australian females constitute only a minority of all Indigenous Australians in the sample, similar to the proportion of female s 32 subjects in general. Again, while the sample size is too limited for meaningful statistical analysis, it is notable that all but one of the five Indigenous women have complex diagnoses.

Taken together, the evidence presented in this and the preceding parts of this article suggest that the s 32 subjects are characterised by marginal and complex diagnoses and by other politicised dimensions of identity that intersect with diagnosed impairment.[49] This highlights that the s 32 subjects do not exist in a biomedical state, void of social and political context, but rather that social and political dimensions are central to an understanding of who these individuals are and to understanding the broader meaning of their impairment.

This part discusses patterns of social disadvantage experienced by the s 32 subjects in the sample and explores the ways in which social disadvantage, gender and Indigeneity intersect with Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder. Social disadvantage is demonstrated via incidence of usage of human services typically associated with economic and social need including out-of-home care, homelessness, housing services (tenancy, rent assistance and evictions), Legal Aid, and disability service support for justice associated needs.

Table 2 shows the pattern of government human services agency contacts for the s 32 subjects in the sample.

Table 2 indicates considerable social disadvantage experienced by s 32 subjects. In general, the table indicates a high incidence of service usage of human services typically associated with economic and social need compounded with some difficulties accessing these services.

Table 2: Section 32 subjects’ agency interactions: raw count and percentage totals*

|

Agency Interactions

|

ID

|

BID

|

MHD

|

MHD_ID

|

MHD_BID

|

Total

|

|

|

Out-of-home Care

|

OOHC

|

2

|

3

|

1

|

7

|

8

|

21

(14.1%)

|

|

No OOHC

|

17

|

17

|

19

|

44

|

31

|

128

(85.9%)

|

|

|

No Fixed Place of Abode

|

NFPA

|

7

|

9

|

14

|

34

|

24

|

88

(59.1%)

|

|

No NFPA

|

12

|

11

|

6

|

17

|

15

|

61

(40.9%)

|

|

|

Housing Tenancy

|

Applied and received

|

5

|

9

|

6

|

19

|

13

|

52

(34.9%)

|

|

Applied did not receive

|

2

|

5

|

3

|

10

|

13

|

33

(22.1%)

|

|

|

Never Applied

|

12

|

6

|

11

|

22

|

13

|

64

(43%)

|

|

|

Evictions

|

Ever Evicted

|

1

|

5

|

2

|

7

|

5

|

20

(13.4%)

|

|

Never Evicted

|

18

|

15

|

18

|

44

|

34

|

129

(86.6%)

|

|

|

Legal Aid

|

Applied

|

14

|

17

|

19

|

44

|

34

|

128

(85.9%)

|

|

Never Applied

|

5

|

3

|

1

|

7

|

5

|

21

(14.1%)

|

|

|

Average Number Legal Aid Cases

|

Applied

|

7.54

|

18.50

|

8.1

|

13.08

|

9.50

|

11.34

|

|

Refused

|

1.25

|

5.29

|

1.13

|

2.25

|

1.6

|

2.3

|

|

|

Department of Ageing Disability and Home Care, Community

Justice Program

|

ADHC Client

|

7

|

2

|

0

|

9

|

6

|

24

(16.1%)

|

|

ADHC – CJP Client

|

3

|

4

|

1

|

14

|

1

|

23

(15.4%)

|

|

|

Not ADHC Client

|

9

|

14

|

19

|

28

|

32

|

102

(68.5%)

|

|

* Key to diagnoses: ID = Intellectual Disability; BID = Borderline Intellectual Disability;

MHD = Mental Health; MHD_ID = Mental Health and Intellectual Disability;

MHD_BID = Mental Health and Borderline Intellectual Disability.

Key to government human services agency interactions: OOHC = out-of-home care;

NFPA = no fixed place of abode; ADHC CJP = Department of Ageing Disability and Home Care, Community Justice Program.

In relation to dynamics in their early lives, 14.1% of the sample have been in outof-home care as children (21 of 149), considerably higher than the rate of outof-home care in the general population of less than 1%.[50] This is significant in light of other critical disability studies research which has identified the relationship between early life disadvantage, poor educational outcomes (notably school exclusion) and criminalisation vis-à-vis people with disability (particularly of racial minorities).[51]

In relation to homelessness, 59% (88 of 149) of the sample have been homeless[52] at some point in their lives. Even within data limitations that mean this is likely an under-representation of actual homelessness, this high proportion of individuals who have been homeless suggests a significant dynamic of social marginalisation. In this group, there is a strong association between complex diagnosis and homelessness (34 of 88 have Mental Health Disorder and Intellectual Disability diagnoses with a further 24 of 88 having Mental Health Disorder and Borderline Intellectual Disability).

Over half of the sample (57%) has applied for public housing (85 of 149). Of this group who have applied for public housing, approximately 60% (52 of 85) were successful in obtaining tenancies. Of the whole sample, 13% (20 of 149) had been evicted from Housing NSW housing. Expressing a need for housing and/or being evicted from public housing is indicative of social disadvantage and while some individuals do have positive housing outcomes, it is clear that for many other s 32 subjects at times this need is not met, suggesting further social disadvantage.

The overwhelming majority of the sample (86%) has applied for Legal Aid at some time in their lives (128 of 149). On average, these individuals made 11 applications and had 2 cases refused. These findings are positive to the extent that they indicate that the s 32 subjects are gaining access to Legal Aid to support them in legal matters. Yet, these findings also point to this group having a number of justiciable problems that might extend beyond the criminal jurisdiction.[53]

A further dimension of social disadvantage in adulthood is the low incidence of access to community disability services. Of those with Cognitive Disability in the sample (ID and BID alone or ID_MHD or BID_MHD: 129 of 149), only 16% (24 of 129) had received disability services from the NSW government disability agency (‘disability service’ or as referred to in Table 2 as ‘ADHC’ services).[54] The picture is no better for access to specialist community forensic disability support, with only 15.4% of s 32 subjects (23 of 149) receiving this specialist service.[55] Given s 32 orders typically require a treatment plan and evidence of disability service access, it is worth noting that there is a high proportion of s 32 subjects with Cognitive Disability who have not received disability services — although some of these s 32 subjects might receive NGO disability services that are funded by the agency, as opposed to services direct from the agency itself. Moreover, those with Cognitive Disability on average first received disability services at a surprisingly older age of 31.9 years. Given that the average age of first police contact for the s 32 subjects with Cognitive Disability is 17 years (as will be discussed in Pt VIII), this indicates that this group may be in the criminal justice system for quite some time prior to receiving disability support services.

Individuals with a single diagnosis of Intellectual Disability had the greatest access to disability services with over 50% (10 of 19) having received a service, while those with a complex diagnosis of Borderline Intellectual Disability and Mental Health Disorder had the lowest access with only 18% (7 of 39) receiving a disability service. When considered in conjunction with the disadvantage experienced by those with Borderline Intellectual Disability in accessing generic human services such as housing and Legal Aid, it is evident that this group experience particularly high levels of social disadvantage, but relatively low levels of support.[56] Indigenous Australians with Cognitive Disability in the sample are particularly marginalised in relation to accessing disability services, with only 17% (8 of 47) of those accessing disability services being Indigenous Australians, despite this group making up 28.2% of all of the s 32 subjects.[57]

The findings presented in Parts V–VII demonstrate that many of the s 32 subjects have marginal and complex diagnoses and that these diagnoses intersect with gender and Indigeneity. Moreover, many of these individuals experience high levels of social disadvantage. Together these show that diagnosed impairment falls short in capturing the individual and institutional dimensions of social disadvantage and obscures important systemic dimensions.

The article now turns from diagnosis, identity and social disadvantage to discuss the criminal justice pathways of the s 32 subjects as alleged offenders. This part begins with a description of the extent and characteristics of s 32 orders as experienced by those in the sample, and then moves beyond the legal event of the s 32 order to look at the pathways over time these individuals take through the criminal justice system as alleged offenders.

All but one of the sample received their s 32 order/s as an adult. Individuals have an average of two such orders, with a range from one (nine individuals) to ten (one individual),[58] with just under half (46%) having received only one s 32 order.

Viewed in isolation, the incidence of s 32 orders might indicate that the s 32 subjects have had contact with the criminal justice system only a small number of times. However, an examination of their longitudinal criminal justice context reveals that s 32 orders are a small part of more complex criminal justice pathways.

The s 32 subjects were, on average, aged 17.2 years at their first police contact (‘FPC’), although it should be noted that there is a considerable spread across the sample in relation to the age of FPC and that some were as young as 9 years old at their age of FPC.[59] Thirty-six per cent were clients of the NSW Department of Juvenile Justice (‘DJJ’) and, of these, 75% have been in DJJ custody. These findings indicate that individuals have been in the criminal justice system for some time and that the majority have early experiences of incarceration, before they receive a s 32 order. Recalling also the poor educational outcomes and high incidence of out-of-home care discussed in Part VII, these children have difficult childhoods and experience criminalisation and institutional failure across institutions.

There are important intersections between diagnosis, other dimensions of politicised identity and early police contact. Indigenous Australians in the sample have a lower average age of FPC of 14.9 years, as compared to 17.4 years for non-Indigenous Australians. Of all Indigenous Australians in the sample, 57% have been DJJ clients, as compared to 27% of non-Indigenous Australian DJJ clients. While Indigenous Australians constitute 28% of the sample, they make up 53% of those who have been in DJJ custody. These findings confirm the concerns expressed in advocacy reports about the high incidence of Indigenous Australians with cognitive impairment in juvenile justice custody.[60]

Individuals in the sample experience contact with the criminal justice system at a young age, including police contact and incarceration during childhood. These findings (particularly when compounded with the findings on social disadvantage and institutional failure) draw attention to the longstanding nature of their criminal justice contact and the significance of institutions to the criminalisation of the group. They raise questions about the extent to which s 32 orders focused on diagnosed impairment can address these temporal and institutional dimensions of the criminalisation of s 32 subjects.

Individuals in the sample also have repeated criminal justice contact — with an average of 97 person of interest (‘POI’) contacts with police. This is a high number given the average age of the sample at the time of the data draw is 35.2 years. Those with a complex diagnosis of Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder have higher average POI contacts (124 contacts) than those with a single diagnosis of Cognitive Disability (85 contacts) and a single diagnosis of Mental Health Disorder (69 contacts).

On average, each individual has been convicted of 38 offences. These convictions continue to occur despite the individuals having received s 32 orders, and the orders themselves are a small proportion of the convicted matters (recalling that the average number of s 32 orders is 2). Further, the average number of convicted offences is much lower than the average number of POI contacts with police (97), illustrating that these individuals have a level of contact with police beyond that associated with the offences in relation to which they are ultimately convicted.

Clear differences are evident in relation to complexity of impairment, where those with a single diagnosis of Cognitive Disability or Mental Health Disorder have, on average, 80 POI contacts and 34 convictions, and those with complex diagnosis of Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder have, on average, 128 POI contacts and 40 convictions. This suggests more intensive criminalisation is associated with complexity of diagnosis.

When POI contacts and convictions are read in conjunction with the findings on FPC and DJJ, it is clear that many of the s 32 subjects come into contact with the police during their childhood and, in turn, cycle in and out of the criminal justice system for a significant part of their life. Moreover, these individuals appear to be subject to ongoing criminalisation as evidenced by the high number of POI contacts — which indicate periodic contact with police as a potential offender, as opposed to only having contact with the criminal justice system in relation to the incidents the subject of the s 32 orders. It is important to note that POI police contact does not necessarily result in formal criminal charges, such that this group’s contact with police is not only broader than their s 32 matter, but also broader than the matters with which they have been charged.

Individuals in the sample tend to be convicted of offences at the less serious end of the scale of criminality. Non-aggravated assault (the least serious form of assault) was the most frequently convicted offence, with a total of 770 convictions across the sample. For 26% of the group, non-aggravated assault is also the most frequent of the most serious convicted offence arising across the cohort. The second most frequently convicted offence is theft (except motor vehicles) with a total of 460 convictions, followed by property damage with a total of 379 convictions. There were no instances of murder, only one instance of manslaughter (recorded for an individual with a single diagnosis of Mental Health Disorder), four instances of attempted murder (all individuals with complex diagnoses of Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder) and two instances of driving causing death (s 32 subject/s with a single diagnosis of Mental Health Disorder). Breach of domestic violence orders, offensive behaviour, offensive language and trespass were other frequently convicted offences. The finding that the sample came into contact with the police and courts generally in relation to low-level criminal offences suggests that while this group do not necessarily pose a serious threat to the community, they experience ongoing criminalisation.

A further dimension of the picture of the criminal justice pathways of the sample is incarceration and its effects. Individuals had, on average, 12 adult (Department of Corrective Services or ‘DCS’) custodial episodes and, on average, spent a total number of 1033 days in adult custody for all those custodial episodes. Thus, these individuals were, on average, likely to cycle in and out of prison on short prison stays and for some this began at a young age through incarceration in juvenile justice detention. Low penalties and the high frequency of movement in and out of prison generates its own disadvantage as individuals are constantly dislocated in housing, service use, drug rehabilitation, and personal relationships.

On average, those with a complex diagnosis of Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder had higher numbers of custodial episodes (14) and total days in custody (1181) for all custodial episodes than for individuals with a single diagnosis of Cognitive Disability or Mental Health Disorder, who had an average of nine custodial episodes and an average total of 806 days in custody. This suggests that the length and frequency of incarceration may be associated with the relative complexity of diagnosis. These findings further indicate that those with complex diagnoses experience multiple problems including greater disadvantage and more cycling in and out of the criminal justice system.

Similar patterns of intensification are also associated with Indigeneity. On average, Indigenous Australians in the sample have roughly the same number of custodial episodes as their non-Indigenous counterparts. However, on average, Indigenous Australians have longer prison stays — with a higher total number of custody days (1259 days) for all custodial episodes than their non-Indigenous counterparts (944 days).

A further dimension to the criminal justice pathways of the sample is the significant vulnerability they experience in incarceration. 62% of individuals in the sample have recorded instances of self-harm in custody. There is noticeable disparity in relation to self-harm in terms of complexity of diagnosis: 69% of those with a diagnosis of Cognitive Disability and Mental Health Disorder have recorded instances of self-harm, whereas 53% of those with a single diagnosis have selfharm instances recorded. This suggests a higher incidence of self-harm associated with complex diagnosis.

The findings presented in Parts VIII(A)–(C) show that s 32 orders form a small part of the overall criminal justice pathways of this group as alleged offenders, and that while the individuals are subject to a high number of convictions, they experience even higher numbers of criminal charges and POI contacts with police. This evidence provides a material basis for the negative effects of the criminal justice system, notably incarceration. While the s 32 subjects clearly have frequent contact with police as POIs, they also have other forms of contact with police which are intimately linked to their criminalisation and hence are significant to the criminal law dimensions of s 32.

Police contact as a victim of crime is significant to the operation of criminal law in relation to the s 32 subjects. On average, the sample have had 15 victim contacts, representing an average 12% of their total POI and victim contacts with police. Those with a single diagnosis of Intellectual Disability experienced the greatest proportion of their police contacts as victims (18%). This is one rare instance in the findings where those with a single diagnosis of Cognitive Disability experience greater levels of disadvantage than those in the complex diagnostic categories.

While small numbers in the sample mean extrapolation for women who receive s 32 orders is not possible, it is interesting to note that females in the sample have higher average numbers of recorded victim contacts when compared to their male counterparts. This gives further nuance to existing research on the intersection of female incarceration, sexual violence and trauma[61] and mirrors previous work on the association between complex diagnosis and criminalisation and victimisation.[62] This is significant in light of the role of violence in the emergence of disability, notably recent statistics on the relationship between gender, Indigeneity, domestic violence and acquired brain injury.[63]

Indigenous Australians in the sample have lower average numbers of recorded victim contacts when compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts, with an average of 11 victim contacts with police, as compared to an average 17 victim contacts for non-Indigenous Australians. This differential may be more likely to be indicative of rates of reporting of victimisation and police recognition of victimisation than of actual victimisation, given that the rate is of victim contacts with police rather than events of victimisation.

The finding presented above indicates that police contact for this group is multidimensional and that members of the sample are in the criminal justice system in a more complex way than only as alleged offenders. It is important to note that the quantitative data cannot provide the context in which victim police contact occurs nor the outcome of these victim police contacts (that is, 10 victim contacts with police does not necessarily mean 10 resolved matters). This is particularly important given research on attrition of complaints of violence made by people with disability generally (particularly women with cognitive and psychosocial disability).[64]

A further dimension of police contact for these individuals is that related to civil mental health legislation, to which the article now turns.

The s 32 subjects in the sample had contact with police under civil mental health legislation. This form of contact was specific to impairment and, more specifically, to police perceptions of their being mentally ill. As such, it demonstrates one way in which impairment provides additional opportunities for criminalisation (discussed in Part IX below). Police have powers under civil mental health legislation to deal coercively with individuals if they appear to have a mental illness. Under this legislation, police can take an individual to a hospital for assessment by a medical practitioner with the view of possible ‘scheduling’ (that is, obtaining legal authority to coercively admit and detain) the individual to a mental health facility for involuntary containment and treatment. Apprehension under these circumstances indicates that police believe the person is experiencing a mental health issue at the time of contact, although this does not necessarily mean that the individual will subsequently receive a mental health related diagnosis and receive treatment; rather it means that the police believe that individual’s behaviour is due to such impairment.

Seventy per cent of the sample have had police contact through civil mental health legislation. For this group, contact pursuant to civil mental health legislation is an additional means of police contact. This might be expected and might point to police using discretion against charging. Importantly, civil mental health legislation expressly excludes ‘developmental disability’ from the definition of ‘mental illness’.[65] Therefore, individuals with Intellectual Disability or Borderline Intellectual Disability do not fall within the legislative definition unless they also have a Mental Health Disorder diagnosis. However, 64% of the sample who had single diagnoses of Cognitive Disability (that is, those with no diagnosis of Mental Health Disorder) had contact with police in relation to the use of the civil mental health legislation. This suggests that mental health diagnosis alone is not the distinguishing factor for contact with police through civil mental health legislation. Thus, the sample came into contact with police in relation to their (actual or perceived) mental illness, suggesting this is a further dynamic of their criminalisation. This civil legal framework effectively creates an additional (and impairment-specific) opportunity for contact with the criminal justice system (and specifically, the police). While the problem of mental health ‘frequent presenters’[66] to police and of mental and public health systems refusing to admit individuals brought to them by police has been noted elsewhere,[67] the police use of mental health legislation specifically in relation to individuals diagnosed with cognitive impairment has not been explored in existing scholarship.

The picture cumulatively developed here of the criminal justice pathways of s 32 subjects is of early and ongoing contact with police, cycling in and out of custody for low-level offences, as well as contact with police as victims of crime. Added to this is the significance of mental health related police contact to the criminal justice pathways of s 32 subjects. This not only shows the complexity and multiple layers of police contact (that exceed the moment of the s 32 order), but also, of concern, the impairment-specific possibilities for additional police contact and the significance of police perceptions of mental illness to this contact (given that many individuals did not, in fact, have any formal diagnoses of mental illness).

The complexity of criminal justice contact over time raises questions about how s 32 fits into the variety of ways the criminal justice system is implicated in lives of people with disability, as well as how s 32 confirms the legitimacy and beneficence of this involvement, rather than acknowledging criminal law and the criminal justice system as themselves part of the problem. So, while prison is clearly negative for this sample and hence it might advantage individuals to not be in prison via a s 32 order, the issue of criminalisation goes beyond prison to multiple legal, spatial, temporal and institutional dimensions of criminalisation. Section 32 orders (in being criminal law orders) do not move individuals outside of these broader dimensions of criminalisation.

To this point, this article has drawn on critical disability studies scholarship to critique the centrality of the legal subject of diagnosed impairment to s 32’s coercive interventions through disability services and mental health treatment. In analysing empirical data on a sample of 149 subjects of s 32 orders, it is important to reiterate that the sample utilised for the study did not capture individuals who had not been prisoners. As such, the findings did not necessarily reflect the experiences of all persons diagnosed with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness in the criminal justice system who have received s 32 orders. However, the level of detail accessible in the data describes the experiences of a purposively selected group and, for the first time, provides insights into the intersections between marginal and complex diagnoses including cognitive impairment and mental health disorder, with other aspects of politicised identity and social disadvantage in childhood and adulthood. Analysis has further highlighted compound criminal justice contact over time, and the significance of victim and mental health contact.

These findings problematise the characterisation of the legal subjects of s 32 in terms of an internal, individual pathologised diagnosed impairment and, in turn, provide a material basis for contesting the coercive effects of s 32. Specifically, the findings point to three particular implications for a more thorough critique of the coercive effects of diversion.

The first implication of the findings presented here is the need for future scholarly, legal, policy and law reform analysis of s 32 to consider how and why individuals with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness come to be reduced to impaired legal subjects for the purpose of s 32, and what happens in the process to the social, political, historical, material and institutional dimensions of their identities and circumstances. The findings provide a stark and important contrast to the construction of the legal subject in s 32 purely or primarily in terms of diagnosed impairment. They prompt the questions of why s 32 does not acknowledge other aspects of politicised identity, and where these aspects go in the legal process of determining a s 32 application. The analysis provides an empirical basis for the suggestion that s 32 is equally exclusionary or silencing of other dimensions of identity and lived experience — dimensions that are widely understood to have significant social and political implications for people with disability in the criminal justice system. This has implications not only for how criminal law can act on individuals, but also for broader consideration of the limits of criminal law in achieving social justice if criminal law cannot respond to and itself is implicated in the complexity of individuals’ marginalisation.

Second, the empirical findings that highlight this sample of s 32 subjects as cycling in and out of prison, experiencing early incarceration and engaging in self-harm in prison all suggest the role the criminal justice system and criminal law have in sustaining criminalisation, social disadvantage and vulnerability and signal the failure of the criminal justice system itself. This prompts questions about the extent to which s 32 is ever capable of addressing the disadvantage, vulnerability and violence that is authorised by criminal law itself. The findings also signal the need to consider how criminal law and the criminal justice system are constructed in s 32, and how the many violent, harmful and negative effects of criminal law and the criminal justice system are acknowledged or ignored in the process of making s 32 orders.

If s 32 cannot acknowledge and address these issues, then the question arises as to the terms on which the interventions enabled through s 32 orders are constructed as necessary and legitimate.

The third implication from the findings is how criminal law acts on people with disability through diversion into the community disability service system. The study presented has given a nuanced picture of the criminal justice contacts of the individuals who have received s 32 orders by creating a longitudinal account of criminal justice contact. This showed that, on average, s 32 subjects had early and ongoing contact with police and multiple episodes of custody, in stark contrast to the very low number of s 32 orders that this sample of individuals had received and the relatively late timing of these orders. The significance of juvenile justice contact (notably, incarceration for Indigenous Australians) and the negligible number of s 32 orders as young persons is indicative of the quantitatively minor and temporally late place of s 32 in the overall criminal justice pathways of the individuals. This means that criminalisation and its negative effects are well entrenched in individuals’ lives by the time s 32 orders are made in adulthood. Therefore, it is likely that there may be complex systemic issues that individuals face, beyond their life circumstances specifically related to the subject charges, which s 32 might be incapable of recognising and addressing. This is particularly the case for the females (notably, Indigenous females) who had received s 32 orders. Analysis also demonstrates the ways that complexity of diagnosis and other dimensions of politicised identity intersect with police contact and incarceration.

The findings prompt questions about the extent to which it is appropriate to have an individual criminal law intervention premised specifically on, and acting through, diagnosed impairment, when the data suggests that there are so many other pervasive social, systemic (and criminal justice) dimensions to the disadvantage and contact with the criminal justice system experienced by people who receive s 32 orders.

The use of community disability services in the specific context of the criminal justice system and s 32 implies belief in the humane nature of these criminal law interventions,[68] yet the findings highlight the limits of using disability services to manage offending. In the case of people with cognitive impairment, which is recognised to be lifelong and permanent, rehabilitative therapy directed at the impairment itself is of limited use. Instead, community disability support is generally angled toward supporting individuals to maximise their capacity in managing the issues of daily life. While skill and capacity building and disability support may go some way to addressing risk factors for offending, these supports in and of themselves also fail to address the criminogenic effects of poverty, intergenerational disadvantage, institutional racism and disablism and the myriad other factors that have been demonstrated in the findings of this research that may act to propel this group toward offending and incarceration.

Critical disability studies scholarship has recognised the depoliticising nature of diagnosed impairment and critiqued, as itself disabling, many of the interventions traditionally associated with contemporary disability service systems that act primarily on impairment. The research of some critical criminologists has also highlighted the role of psychological and medical services in prison as depoliticising the violence of incarceration.[69] Taken together these critiques suggest the need to consider the coercive effects of s 32 that are premised on intervention and amelioration of impairment, while bracketing off impairment itself from the social context in which it arises and the social processes that see it become entwined with offending for some individuals. This highlights the ways in which the use of community disability services in s 32 reconciles the discourses of support, empowerment and inclusion with which they are typically associated and their coercive and punitive effects in the state’s administration of criminal law. Humane motivations for community disability services also mask the coercive and punitive effects those services can have on individuals with cognitive impairment in the criminal law context of s 32. Here, there is the risk that discourses of rights and inclusion might be used to legitimise what might be viewed as punitive, oppressive or disciplinary in other contexts.[70]

This article has raised questions about the role of criminal law and the criminal justice system vis-à-vis non-convicted individuals with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness in the criminal justice system. While s 32 might arguably perform an important function by identifying people in the community who need help and linking them with services, we have argued that this function is limited because diversion acts only on impairment (in a narrow, diagnostic sense) and its consequences, and obviates attention to the complex social production of impaired offenders. The ultimate question here is a much deeper one — should criminal law be fulfilling this role or does its role signal a broader social failure to respond to marginality and its complex causation in this group of individuals? Without question, s 32 — as a short-term measure — has benefits over incarceration, but its immediate function simultaneously prevents engagement in a deeper consideration of where s 32 might fit both in broader issues faced by individuals with cognitive impairment and/or mental illness in the criminal justice system and in a political vision for addressing marginalisation of people with disability in the wider social landscape.

[∗] Lecturer, School of Law, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia. This work was supported by an Endeavour Foundation Endowment Challenge Fund Student Grant awarded to Linda Steele.

[†] Associate Professor, Chair in Intellectual Disability and Behaviour Support, School of Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

[‡] Research Assistant, School of Social Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

[1] The support for s 32 is most recently evident in the consistent support that the provision has received in public submissions made to the New South Wales Law Reform Commission (‘NSWLRC’) review of persons with mental health and cognitive impairment in the criminal justice system: NSWLRC, People with Cognitive and Mental Health Impairments in the Criminal Justice System — Submissions <http://www.lawreform.justice.nsw.gov.au/Pages/lrc/lrc_completed

_projects/lrc_completedprojects2010.aspx>. In relation to law reform organisations see NSWLRC, People with Cognitive and Mental Health Impairments in the Criminal Justice System: Diversion, Consultation Paper No 7 (2010) (‘NSWLRC Consultation Paper No 7’); NSWLRC, People with Cognitive and Mental Health Impairments in the Criminal Justice System: Diversion, Report No 135 (2012) (‘NSWLRC Report No 135’). In relation to disability advocacy organisations, see Andrew Howell and Linda Steele, ‘Enabling Justice — A Report on Problems and Solutions in Relation to Diversion of Alleged Offenders with Intellectual Disability from the New South Wales Local Courts System: With Particular Reference to the Practical Operation of s 32 of the Mental Health (Criminal Procedure) Act 1990 (NSW)’ (Report, Intellectual Disability Rights Service, May 2008); Nick Rushworth, ‘Out of Sight, Out of Mind: People with an Acquired Brain Injury and the Criminal Justice System’ (Policy Paper, Brain Injury Australia, July 2011). In relation to legal professionals, see Peter McGhee and Siobhan Mullany, ‘Keeping People with Intellectual Disability Out of Jail’ (2007) 83 Precedent 16; Peter McGhee and Lee-May Saw, ‘Chiselling the Bars: Acting for People with an Intellectual Disability’ (2005) 43(9) Law Society Journal 61; Karen Weeks, ‘To Section 32 or Not?: Applications under s 32 Mental Health (Forensic Provisions) Act 1990 in the Local Court’ (2010) 48(4) Law Society Journal 49. In relation to forensic mental health and disability service providers, see David Greenberg and Ben Nielsen, ‘Court Diversion in NSW for People with Mental Health Problems and Disorders’ (2002) 13(7) NSW Public Health Bulletin 158; David Greenberg and Ben Nielsen, ‘Moving Towards a Statewide Approach to Court Diversion Services in NSW’ (2003) 14(11–12) NSW Public Health Bulletin 227.

[2] Elizabeth Richardson and Bernadette McSherry, ‘Diversion Down Under — Programs for Offenders with Mental Illnesses in Australia’ (2010) 33(4) International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 249; Tamara Walsh, ‘Diverting Mentally Ill Women Away from Prison in New South Wales: Building on the Existing System’ (2003) 10(1) Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 227.

[3] NSWLRC Consultation Paper No 7, above n 1; NSWLRC Report No 135, above n 1.

[4] However, see Linda Roslyn Steele, Disability at the Margins: Diversion, Cognitive Impairment and the Criminal Law (PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2014); Linda Steele, ‘Diversion of Individuals with Disability from the Criminal Justice System: Control Inside or Outside Criminal Law?’ in Alan Reed, Chris Ashford and Nicola Wake (eds), Consent and Control: Legal Perspectives on State Power (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, forthcoming).

[5] Steele, ‘Diversion of Individuals with Disability from the Criminal Justice System’, above n 4.

[6] MHFP Act s 32(1)(a).

[7] Susanna Every-Palmer et al, ‘Review of Psychiatric Services to Mentally Disordered Offenders Around the Pacific Rim’ (2014) 6(1) Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 1; Richardson and McSherry, above n 2; Richard D Schneider, ‘Mental Health Courts and Diversion Programs: A Global Survey’ (2010) 33(4) International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 201.

[8] MHFP Act ss 3(1) (definition of ‘Magistrate’), 32.

[9] This includes whether or not a defendant is fit to plead and whether or not a plea has been entered: Perry v Forbes (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Smart J, 21 May 1993); Mantell v Molyneux [2006] NSWSC 955; (2006) 68 NSWLR 46, 59–60 [49].

[10] Intellectual Disability Rights Service, Step By Step Guide to Making a Section 32 Application for a Person with Intellectual Disability (2011) 22–32.

[11] (2006) 66 NSWLR 93, 109–10 [75]–[80] (McColl JA) (‘El Mawas’).

[12] MHFP Act s 32(1)(a).

[13] El Mawas (2006) 66 NSWLR 93, 109 [75] (McColl JA).

[14] MHFP Act s 32(1)(b).

[15] Particular factors have been identified in the case law. See El Mawas (2006) 66 NSWLR 93, 95 [6], [8], [10] (Spigelman CJ), 109–10 [77]–[79], [84] (McColl JA); Mantell v Molyneux [2006] NSWSC 955; (2006) 68 NSWLR 46, 57–8 [40]–[41], 59 [47]–[48]; DPP (NSW) v Soliman [2013] NSWSC 346 (16 April 2013) [59]. See also Broome v Liristis [2011] NSWDC 40 (15 June 2011) [40]–[42]; Police v Goodworth [2007] NSWLC 2 (28 March 2007) [1]; Police v Winter [2008] NSWLC 15 (22 August 2008); Quinn v DPP (NSW) [2015] NSWCA 331 (16 October 2015).

[16] El Mawas (2006) 66 NSWLR 93, 110 [80] (McColl JA).

[17] Ibid 108 [71] (McColl JA).

[18] For the suggested form that the s 32 order should take, see Judicial Commission of New South Wales, Local Court Bench Book (at Service 117) [35-060].

[19] MHFP Act s 32(3)(c).

[20] Ibid ss 32(3)(a)–(b), (3A), (3D).

[21] Ibid s 32(2).

[22] Ibid s 32A.

[23] Ibid ss 32(3A)–(3D).

[24] Steele, ‘Diversion of Individuals with Disability from the Criminal Justice System’, above n 4.

[25] Richard Devlin and Dianne Pothier, ‘Introduction: Toward a Critical Theory of Dis-Citizenship’ in Dianne Pothier and Richard Devlin (eds), Critical Disability Theory: Essays in Philosophy, Politics, Policy, and Law (UBC Press, 2006) 1, 2.

[26] See, eg, Dan Goodley, Dis/Ability Studies: Theorising Disablism and Ableism (Routledge, 2014). See also Mairian Corker and Tom Shakespeare, ‘Mapping the Terrain’ in Mairian Corker and Tom Shakespeare (eds), Disability/Postmodernity: Embodying Disability Theory (Continuum, 2002) 1; Shelley Tremain, ‘Foucault, Governmentality, and Critical Disability Theory: An Introduction’ in Shelley Tremain (ed), Foucault and the Government of Disability (University of Michigan Press, 2005) 1; Shelley Tremain, ‘On the Subject of Impairment’ in Mairian Corker and Tom Shakespeare (eds), Disability/Postmodernity: Embodying Disability Theory (Continuum, 2002) 32.

[27] Nirmala Erevelles, Disability and Difference in Global Contexts: Enabling a Transformative Body Politic (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011); Camilla Lundberg and Eva Simonsen, ‘Disability in Court: Intersectionality and Rule of Law’ (2015) 17(Supplement 1) Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 7; Helen Meekosha, ‘What the Hell are You? An Intercategorical Analysis of Race, Ethnicity, Gender and Disability in the Australian Body Politic’ (2006) 8(2–3) Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 161.

[28] See, eg, Raewyn Connell, ‘Southern Bodies and Disability: Re-Thinking Concepts’ (2011) 32(8) Third World Quarterly 1369; Leanne Dowse, Eileen Baldry and Phillip Snoyman, ‘Disabling Criminology: Conceptualising the Intersections of Critical Disability Studies and Critical Criminology for People with Mental Health and Cognitive Disabilities in the Criminal Justice System’ [2009] AUJlHRights 8; (2009) 15(1) Australian Journal of Human Rights 29; Erevelles, above n 27; David Hollinsworth, ‘Decolonizing Indigenous Disability in Australia’ (2013) 28(5) Disability & Society 601; Beth Ribet, ‘Naming Prison Rape as Disablement: A Critical Analysis of the Prison Litigation Reform Act, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and the Imperatives of Survivor-Oriented Advocacy’ (2010) 17(2) Virginia Journal of Social Policy and the Law 281; Beth Ribet, ‘Surfacing Disability Through a Critical Race Theoretical Paradigm’ (2010) 2(2) Georgetown Journal of Law & Modern Critical Race Perspectives 209; Beth Ribet, ‘Emergent Disability and the Limits of Equality: A Critical Reading of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ (2011) 14(1) Yale Human Rights & Development Law Journal 155; Ivan Eugene Watts and Nirmala Erevelles, ‘These Deadly Times: Reconceptualizing School Violence by Using Critical Race Theory and Disability Studies’ (2004) 41(2) American Educational Research Journal 271.

[29] In an empirical context in Australia, see Eileen Baldry, Leanne Dowse and Melissa Clarence, ‘People with Intellectual and Other Cognitive Disability in the Criminal Justice System’ (Report, NSW Family & Community Services: Ageing, Disability & Home Care, December 2012). On a more theoretical level, see generally Liat Ben-Moshe, Chris Chapman and Allison C Carey (eds), Disability Incarcerated: Imprisonment and Disability in the United States and Canada (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014); Dowse, Baldry and Snoyman, above n 28. There is a growing body of literature highlighting the issues concerning Indigenous Australians with disability in the criminal justice system: Eileen Baldry et al, A Predictable and Preventable Path: Aboriginal People with Mental and Cognitive Disabilities in the Criminal Justice System (2015); Peta MacGillivray and Eileen Baldry, ‘Indigenous Australians, Mental and Cognitive Impairment and the Criminal Justice System: A Complex Web’ [2013] IndigLawB 52; (2013) 8(9) Indigenous Law Bulletin 22; Tom Calma, ‘Preventing Crime and Promoting Rights for Indigenous Young People with Cognitive Disabilities and Mental Health Issues’ (Report No 3, Australian Human Rights Commission, March 2008); Jim Simpson and Mindy Sotiri, ‘Criminal Justice and Indigenous People with Cognitive Disabilities’ (Discussion Paper, Beyond Bars Alliance, 2004); Mindy Sotiri, Patrick McGee and Eileen Baldry, ‘No End in Sight: The Imprisonment, and Indefinite Detention of Indigenous Australians with a Cognitive Impairment’ (Report, Aboriginal Disability Justice Campaign, September 2012); Julian Trofimovs and Leanne Dowse, ‘Mental Health at the Intersections: The Impact of Complex Needs on Police Contact and Custody for Indigenous Australian Men’ (2014) 37(4) International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 390. In relation to Indigeneity, race, disability and the criminal justice system on a more theoretical level, see, eg, Chris Chapman, ‘Five Centuries’ Material Reforms and Ethical Reformulations of Social Elimination’ in Liat Ben-Moshe, Chris Chapman and Allison C Carey (eds), Disability Incarcerated: Imprisonment and Disability in the United States and Canada (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) 25; Hollinsworth, above n 28; Ribet, ‘Naming Prison Rape as Disablement’, above n 28; Watts and Erevelles, above n 28.

[30] See, eg, Tremain, ‘Foucault, Governmentality, and Critical Disability Theory’, above n 26; Tremain, ‘On the Subject of Impairment’, above n 26.

[31] See, eg, Tremain, ‘Foucault, Governmentality, and Critical Disability Theory’, above n 26, 10–11.