Sydney University Press Law Books

|

[Home]

[Databases]

[WorldLII]

[Search]

[Feedback]

Sydney University Press Law Books |

|

2006 marked the 30th anniversary of the US Copyright Act 1976,[1] 2008 marks the 40th anniversary of the Australian Copyright Act 1968[2] and 2010 marks the 300th anniversary of the Statute of Anne. There is no doubt that concepts about how to manage, control and share knowledge, culture and creativity existed in societies well before 1709/10[3] but it is the Statute of Anne that is the symbolic birthplace of what we know as modern copyright law.[4]

As we enter an era of unprecedented knowledge and cultural production and dissemination we are challenged to reconsider the fundamentals of copyright law and how it serves the needs of life, liberty and economy in the 21st century. More radical proposals advocate the abolition of any legislative and regulatory regime in order to leave the trading (both commercial and non commercial) of ideas to other mechanisms such as politics, the market or social networks. More moderate reforms – within the framework of the current regime – have been the centre of discussion at Professor Hugh Hansen’s Fordham International Intellectual Property Conference (2007), a specialist workshop run by Professor Pamela Samuelson in July 2007 in Napa Valley[5] and will be further discussed at a world congress proposed by creative economy guru and Adelphi Charter[6] figurehead John Howkins[7] to celebrate or commiserate the Statute of Anne in 2010.

The way in which culture is represented, reproduced and communicated to the world has vastly changed. We live in an era where any person of any age can email, blog, podcast, make entries in Wikipedia[8] or upload a home crafted or user generated video to YouTube[9] in the blink of an eye to a world wide audience of hundreds of millions of people. This is driven by an incredible capacity to search the world wide web through search engines such as Google,[10] Yahoo[11] and Baidu[12]. Creativity and sharing have taken on incredible new dimensions.

The centre point of this Web 2.0[13] style activity is the “social network” – a space for making friends and sharing knowledge and creativity.[14] The social network is epitomised by well known spaces such as MySpace,[15] Facebook,[16] Flickr[17] and YouTube[18] but is also evident in the millions of blogs, live chat rooms and wikis that exist throughout the Internet world.

Within the social network people create things in and provide thoughts from their bedrooms, studies, lounge rooms, cafes and offices and communicate them via the network to the outside world. Sharing amongst participants within the social network tends to be on a non commercial basis. In fact that seems to be the unwritten norm underpinning activity within the social network environment – non commercial use by each other is permitted.

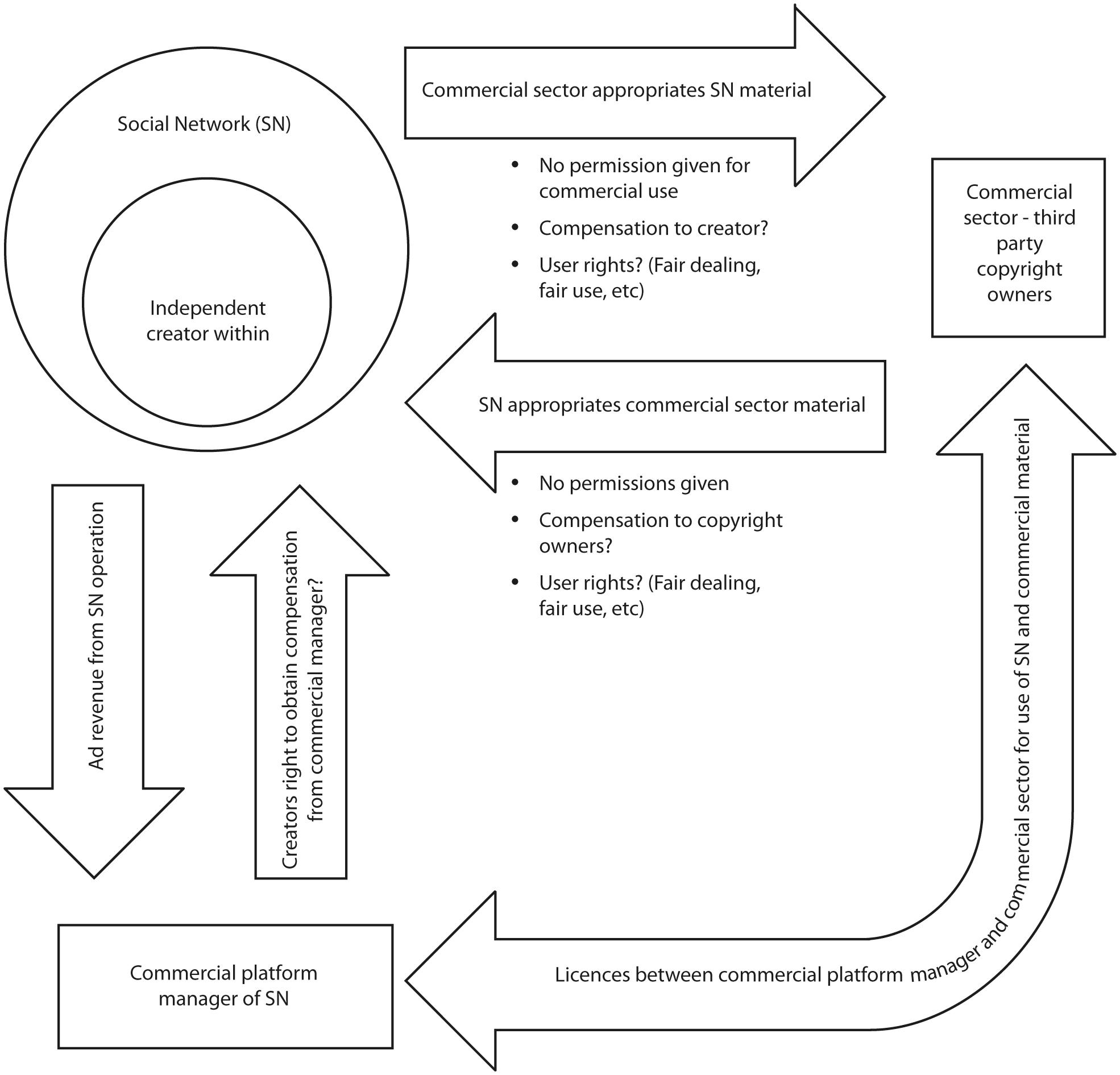

However once the material created and distributed through the social network is deposited into or utilised within a commercial domain or enterprise for financial reward then this norm subsides and compensation may be sought. Likewise material utilised or distributed by the social network that is taken from the commercial domain or network, eg Hollywood, under current law, will need to be fair use, licensed and/or paid for. More so, the social network is underpinned by a technological platform and the provider of such platforms will often seek “revenue” through advertising and subscription fees. These commercial platform operators such as Google (YouTube), Yahoo (Flickr) and News Corporation (MySpace) are some of the largest corporations in the world and they are profiting handsomely off the social network. It remains unclear to what extent they should be sharing profits with the creatives of the social network (which sites like Revver[19] do) or where commercially released material has been utilised how much they should be paying the commercial sector from where it is sourced e.g. Hollywood – the substance of the issue being litigated in Viacom v YouTube and Google.[20]

The following diagram highlights these complex new relationships between the non commercial and commercial domains.

This large scale implementation of social activity along with the commercial consumption of entertainment in an online digital world where reproduction and communication is both ubiquitous and automated by use brings the need for a fundamental rethinking of copyright law.

The following are eleven points that (at very least) should be examined or taken into consideration in any copyright reform agenda. An agenda that one would hope will be well under way by 2010. For every day we stand entrenched in the legacy models of the past we are denying the opportunity of the future.

1. International treaties: Do they reflect the needs of the networked information society we now live in? How will the access to knowledge and development agenda currently before the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) change the way these treaties are drafted? By 2004, WIPO was facing increasing demands from developing countries for intellectual property regimes to reflect a more appropriate balancing of interests, to better serve health, education and culture. These demands are summarised in the Draft Access to Knowledge Treaty (2005).[21] At the first meeting of WIPO's Provisional Committee on Proposals Related to a Development Agenda (PCDA) in February 2006, the participants listed a total of 111 proposals for strengthening the focus on development in WIPO’s work. At the third session of the PCDA, held in Geneva in February 2007, participants agreed on an initial set of proposals for inclusion in the final list of proposals to be recommended to the 2007 WIPO General Assembly. The recommendations are clustered under six headings relating to WIPO’s work in the areas of technical assistance and capacity building; norm-setting, flexibilities, public policy and public domain; technology transfer, information and communication technologies (ICT) and access to knowledge; assessment, evaluation and impact studies; institutional matters including mandate and governance and certain other issues.[22]2. Subject Matter, Exclusive rights and Ownership: Has the digital era transformed the existing exclusive rights of the copyright owner into something too broad and all encompassing? Is there scope for the development of an attribution only copyright (attribution being the only enforceable exclusive right) within the social network where non commercial reuse is the underlying principle? Who is an author in the interactive and iterative wiki blog based user generated world which we now inhabit?[23] To what extent does changing the scope of the exclusive rights fall outside the Berne Convention’s “three step test”?[24] Should copyright subject matter be narrowed or extended to include, for example, “webcasting”?[25] Should it require fixation?[26] Do ownership rights carry any sense of obligation to the “information environment”?[27] What should we do with traditional cultural expression (TCE) and other indigenous cultural issues?[28]

3. User rights or limitations: To what extent should user rights continue to be seen as subservient to owner rights?[29] What new user rights are needed for this new environment?[30] For example, there is a growing need to sensibly articulate the right to engage in transformative reuse of copyright material in international and national laws.[31]

4. Crown, government or publicly funded copyright: In countries where government or publicly funded copyright exists there should be close consideration given to expressly allowing broad rights, of at very least, non commercial dissemination and reuse.[32]

5. Non Commercial Use: How far should we be allowed to reuse material for designated non commercial purposes?[33] How does non commercial distribution occur in a world which allows such good quality and broad scale distribution – doesn’t it all impact on the commercial return? Is sharing in a social network really non commercial – don’t major corporations benefit financially from this and what price should they pay? Is non commercial use an issue of more closely defining exclusive rights which do not at present distinguish between commercial and non commercial uses or an issue for exceptions, limitations or user rights?

6. Intermediary liability: Today we have a plethora of intermediaries, yet the “safe harbours” were designed in an era where ISPs were the dominant intermediary. As we now have so many different levels of intermediary the whole landscape of liability for the messenger needs to be reviewed.[34] In doing so the concept of “notice and take down” (as embodied in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act 1998 (DMCA)) or “notice and notice”, as a form of copyright compliance needs to be more closely considered.

7. Secondary, authorisation or contributory liability: The more we expand this type of liability the more we risk chilling diversity of opportunity and innovation: see Justice Stephen Breyer of the US Supreme Court in Grokster.[35] We need to closely asses the scope and role of legislation in this regard and ask whether this is an activity where the market would be the better point of regulation as in Schumpeterian terms innovation is fundamentally about how the market reshapes itself through new ways of doing things.[36]

1. Licensing Models: We also need to encourage and devise new licensing models to fit the technologies – Apple iTunes (direct licensing),[37] NOANK Media (ISP level licensing)[38] and Creative Commons (open licensing)[39] provide recent examples. Never again should we allow everyday people to be put in the position of facing criminal charges because industry has been unwilling to provide new business models.[40] The notion of compulsory licensing and collective administration of copyright will also be implicated in this discussion.[41]2. New Business Models: As part of the way of solving copyright issues in the digital environment and moving with the technology, commerce must explore new business models that facilitate access in the name of creativity and knowledge. In some instances, by allowing broader access we open up more social and economic opportunity – downstream multipliers that are otherwise choked by revenue seeking too early in the process. In the words of Varian and Shapiro from Information Rules we need to “maximise value not protection”.[42]

3. Creator Utopia: The rise of the user generated phenomenon has led some to suggest that the copyright law of the future might be more effectively utilised by creators. In the last 300 years the copyright regime while built around the romantic notion of the author has largely facilitated the wealth of the commercialising agents such as publishers, movie studios and recording companies. Will this change as a result of any new found independence of and distribution/communication networks for 21st century authors?

4. World Trade and Politics: There can be little doubt that the dominance of the US led “pay for every use” “maximalist” view of copyright has been seriously questioned. Countries like India and Brazil are challenging the status quo and the role China will play in influencing the new contours of copyright cannot be underestimated. It seems inevitable that China as the country with the largest number of internet users – over 100 million – will learn how to harness the power of We-Media before many others. It is no surprise that in late 2007 the subject of copyright is a matter of contention between the hegemonic forces of the US and China before the World Trade Organisation (WTO).[43]

The forgoing discussion highlights some[44] of the key areas that need to be considered in any process of copyright reform. In my view by 2010 we should be moving beyond the limited conceptual framework of copyright to a legal framework that looks more closely at the relationships any individual or entity has with information, knowledge, culture or creativity. A crude name would be Information or Cultural Relationship Law. By focussing on the information or cultural resource and how we nurture and allocate it for social and economic good we open up the politics and economy of the rights to access, reuse and communicate information, knowledge, culture or creativity.

The momentum in this process will not only be driven by the members of the new online social network and communities but also by the mega access corporations that underpin this new space. These access corporations – such as Google, Yahoo – work on a business model in which the more access to content that is available the wealthier they become. While the Viacom v YouTube and Google case may only be the first iteration of the political dynamic at play we are seeing a fundamental reshaping of copyright politics. No longer is the access or user or development agenda being championed solely by people or entities that are seen as the less powerful challengers or outsiders, but now it is being championed by heavy hitting mainstream US based western corporations.

In short, the future of copyright provides a dynamic and challenging topic for discussion and action as we move towards 2010.

[1] The previous statutes at the federal level were the Act of 31 May 1790 (further statutes introduced new subject matter and expanded the scope and term of protection in 1802, 1819, 1831, 1834, 1846, 1855, 1856, 1859, 1861, 1865, 1867, 1870, 1873, 1874, 1879, 1882, 1891, 1893, 1895, 1897, 1904 and 1905) and the Copyright Act 1909. See: B Kaplan, An Unhurried View of Copyright (1966) 25-6, 38-9.

[2] The previous statutes at the federal level were the Copyright Act 1905 and the Copyright Act 1912. For further discussion of these acts of parliament see: B Atkinson, The True History of Copyright (2007).

[3] R Versteeg, ‘The Roman Law Roots of Copyright’ (2000) 59 Maryland Law Review 522; P E Geller, ‘Copyright History and the Future: What’s Culture Got To Do With It?’ (2000) Journal of Copyright Society of the USA 209, 210-15; M Barambah and A Kukoyi, ‘Protocols for the Use of Indigenous Cultural Material’ in A Fitzgerald et al (ed), Going Digital 2000: Legal Issues for E-Commerce, Software and the Internet (2000) 133.

[4] P Samuelson, ‘Copyright and Freedom of Expression in Historical Perspective’ (2003) 10 Journal of Intellectual Property Law 319, 324; B Kaplan, An Unhurried View of Copyright (1966); R Patterson, Copyright in Historical Perspective (1968); S Ricketson and C Creswell, The Law of Intellectual Property: Part II Copyright and Neighbouring Rights, Ch 3 documenting the numerous copyright statutes to follow on from the Statute of Anne in the UK at [3.230] ff, [3.280], [3.370]. On the origins of modern copyright elsewhere in Europe see: G Davies, Copyright and the Public Interest (2nd ed, 2002) Ch 3.

[5] See further: P Samuelson, ‘Preliminary Thoughts on Copyright Reform’ forthcoming (2007) Utah Law Review <http://people.ischool.berkeley.edu/~pam/papers.html> at 25 January 2008.

[6] Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce (RSA), Adelphi Charter on Creativity, Innovation and Intellectual Property. See further at <http://www.adelphicharter.org> .

[7] J Howkins, The Creative Economy: How People Make Money from Ideas (2001).

[8] <http://www.wikipedia.com> .

[9] <http://www.youtube.com> .

[10] <http://www.google.com> .

[13] On this concept see: T O’Reilly, What is Web 2.0 (2005) <http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html> at 25 January 2008.

[14] See generally: ‘Social Network’ in Wikipedia <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_network> at 25 January 2008; ‘Social Network Service’ in Wikipedia <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_network_service> at 25 January 2008.

[15] <http://www.myspace.com> .

[16] <http://www.facebook.com> .

[17] <http://www.flickr.com> .

[18] <http://www.youtube.com> .

[19] <http://www.revver.com> .

[20] Viacom International Inc v YouTube Inc, (SD NY, filed 13/3/2007). The Viacom complaint is here <www.paidcontent.org/audio/viacomtubesuit.pdf> at 25 January 2008 and the Youtube and Google response is here <http://news.com.com//pdf/ne/2007/070430_Google_Viacom.pdf> at 25 January 2008. For a debate between their respective lawyers see: <http://theutubeblog.com/2007/04/15/viacom-v-youtubegoogle-their-lawyers-debate-lawsuit> at 25 January 2008. A critical issue in this litigation will be the application of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act 1998 (DMCA) so called ‘safe harbours’ for intermediaries: see further Perfect 10 Inc v CCBill LLC (9th Cir, 2007) <http://www.ca9.uscourts.gov/ca9/newopinions.nsf/08468E0D5E386A2F882572AC0077AD1A/$file/0457143.pdf> L Lessig, ‘Make Way for Copyright Chaos’, New York Times, 18 March 2007, <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/18/opinion/18lessig.html?ex=1331870400 & en=a376e7886d4bcf62 & ei=5088 & partner=rssnyt> at 25 January 2008.

[21] Draft Access to Knowledge Treaty (2005) <http://www.access2knowledge.org/cs/a2k> at 25 January 2008.

[22] See World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), ‘Member States Make Significant Headway in Work on a WIPO Development Agenda’ (Press Release 2007/478, 26 February 2007) <http://www.wipo.int/pressroom/en/articles/2007/article_0011.html> at 25 January 2008; WIPO Director General Welcomes Major Breakthrough following Agreement on Proposals for a WIPO Development Agenda Geneva’ (Press Release 18 June 2007) <http://www.wipo.int/pressroom/en/articles/2007/article_0037.html> at 25 January 2008; ‘Member States Adopt a Development Agenda for WIPO’ (Press Release 1 October 2007) <http://www.wipo.int/pressroom/en/articles/2007/article_0071.htm> at 25 January 2008.

[23] See Erez Reuveni, ‘Authorship in the Age of Conducer’ (2007) 54 Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA, 286.

[24] Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works 1886, art 9(2) provides: ‘It shall be a matter for legislation in the countries of the (Berne) Union to permit the reproduction of such works in certain special cases, provided that such reproduction does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author.’ See also WIPO Copyright Treaty 1996 (WCT) art 10, WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty 1996 (WPPT) art 16, Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights 1994 (TRIPS) art 13.

[25] See the proposed WIPO Broadcasting Treaty; WIPO, ‘Negotiators Narrow Focus in Talks on a Broadcasting Treaty’ (Press Release 2007/473, 22 January 2007) <http://www.wipo.int/pressroom/en/articles/2007/article_0003.htm> at 25 January 2008; ‘Briefing Paper on the Proposed WIPO Broadcasting Treaty, Second Special Session of SCCR’, Electronic Frontier Foundation, 18 June 2007 <http://www.eff.org/IP/WIPO/broadcasting_treaty/EFF_wipo_briefing_paper_062007.pdf> at 25 January 2008.

[26] P Samuelson, ‘Preliminary Thoughts on Copyright Reform’ forthcoming (2007) Utah Law Review <http://people.ischool.berkeley.edu/~pam/papers.html> at 25 January 2008.

[27] J Boyle, A Politics of Intellectual Property: Environmentalism for the Net? Duke University School of Law <http://www.law.duke.edu/boylesite/Intprop.htm> at 25 January 2008.

[28] WIPO, Draft Provisions on the Protection of Traditional Cultural Expressions/Folklore and Traditional Knowledge <www.wipo.int/tk/en/consultations/draft_provisions/draft_provisions.html> at 25 January 2008; B Fitzgerald and S Hedge, ‘Traditional Cultural Expression and the Internet World’ in C Antons (ed), Traditional Knowledge, Traditional Cultural Expression and Intellectual Property in South East Asia (2007).

[29] Consider: CCH Canadian Ltd v Law Society of Upper Canada [2004] 1 SCR 339 <http://www.canlii.org/en/ca/scc/doc/2004/2004scc13/2004scc13.html> at 25 January 2008; J Cohen, ‘The Place of the User in Copyright Law’ (2005) 74 Fordham Law Review 347.

[30] Consider: Authors Guild v Google Print Library Project <http://www.boingboing.net/images/AuthorsGuildGoogleComplaint1.pdf> at 25 January 2008; McGraw-Hill Companies Inc, Pearson Education Inc, Penguin Group (USA) Inc, Simon & Schuster Inc and John Wiley & Sons Inc v Google Inc <http://www.boingboing.net/2005/10/19/google_sued_by_assoc.html> at 25 January 2008; J Band, The Authors Guild v The Google Print Library Project (2005) LLRX.com <http://www.llrx.com/features/googleprint.htm> at 25 January 2008.

[31] See: Gowers Review of Intellectual Property (2006) 67-8 <http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/media/6/E/pbr06_gowers_report_755.pdf> at 25 January 2008; Perfect 10 Inc v Amazon Com Inc [2007] USCA9 270; 487 F 3d 701 (9th Cir, 2007)

[32] See generally: B Fitzgerald et al, Internet and E Commerce Law: Technology, Law and Policy (2007) Ch 4; Intrallect Ltd and AHRC Research Centre, The Common Information Environment and Creative Commons, Final Report (2005), Ch 3.6 <http://www.intrallect.com/cie-study> at 25 January 2008; Open Access to Knowledge (OAK) Law Project, Creating a Legal Framework for Copyright Management of Open Access within the Australian Academic and Research Sectors, Law Report No 1 (2006) <http://www.oaklaw.qut.edu.au> at 5 March 2007; Queensland Spatial Information Council (QSIC), Government Information and Open Content Licensing: An Access and Use Strategy (2006) <http://www.qsic.qld.gov.au/qsic/QSIC.nsf/CPByUNID/BFDC06236FADB6814A25727B0013C7EE> at 25 January 2008.

[33] J Litman, Digital Copyright (2001) Ch 12.

[34] M Lemley, ‘Rationalising Internet Safe Harbours’ (Working Paper No 979836, Stanford Public Law, 2007) <http://www.law.stanford.edu/publications/details/3657/Rationalizing%20Internet%20Safe%20Harbors> at 25 January 2008; Brian Fitzgerald, Damien O'Brien and Anne Fitzgerald, ‘Search Engine Liability for Copyright Infringement’ in Amanda Spink and Michael Zimmer (eds), Web Searching: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (2008).

[35] MGM Studios Inc v Grokster Ltd 545 US 913 (2005).

[36] J Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942).

[37] <http://www.apple.com/itunes> .

[38] <http://www.noankmedia.com> .

[39] <http://www.creativecommons.org> Lawrence Lessig, Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity (2004) <http://www.free-culture.cc/freeculture.pdf> at 25 January 2008; B Fitzgerald, J Coates, and S M Lewis (eds) Open Content Licensing: Cultivating the Creative Commons (2007) <http://eprints.qut.edu.au/archive/00006677> at 25 January 2008.

[40] Consider: W Fisher, Promises to Keep: Technology, Law and the Future of Entertainment (2004); N Netanel, ‘Impose a Non Commercial Use Levy to Allow Free P2P File Sharing’ (2003) 17 Harvard Journal of Law and Technology 1.

[41] Consider the recent activities of the European Commission in relation to CISAC: European Union, ‘Competition: Commission sends Statement of Objections to the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers (CISAC) and its EEA Members’ (Press Release MEMO/06/63, 7 February 2006) <http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=MEMO/06/63 & format=HTML & aged=1 & language=EN & guiLanguage=en> at 25 January 2008; European Union, ‘Antitrust: Commission Market Tests Commitments from CISAC and 18 EEA Collecting Societies Concerning Reciprocal Representation Contracts’ (Press Release IP/07/829, 14 June 2007) <http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=IP/07/829 & type=HTML & aged=0 & language=EN & guiLanguage=en> at 25 January 2008.

[42] Carl Shapiro and Hal Varian, Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy (1999) 4.

[43] Dispute Settlement DS362, China – Measures Affecting the Protection and Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights (Complainant: United States of America) <http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds362_e.htm> at 25 January 2008; Dispute Settlement DS363, China – Measures Affecting Trading Rights and Distribution Services for Certain Publications and Audiovisual Entertainment Products (Complainant: United States of America) <http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds363_e.htm> at 25 January 2008.

[44] Many others issues could be raised, e.g., the length of copyright term, the scope and rationale for moral rights, the criminalisation of copyright infringement, the intersection of copyright and contract/licensing, digital rights management and technological protection measures and proposals for registration and simplification: see Eldred v Ashcroft [2003] USSC 722; 537 US 186 (2003); Golan v Gonzales 501 F. 3d 1179 (10 Cir. 2007); Chan Nai Ming v HHSAR (Court of Final Appeal, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, 18 May 2007); Stevens v Kabushiki Kaisha Sony Computer Entertainment [2005] HCA 58 <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/HCA/2005/58.html> at 25 January 2008; P Samuelson, ‘Preliminary Thoughts on Copyright Reform’ forthcoming (2007) Utah Law Review <http://people.ischool.berkeley.edu/~pam/papers.html> at 25 January 2008; Lawrence Lessig, Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity (2004) <http://www.free-culture.cc/freeculture.pdf> at 25 January 2008; P E Geller, ‘Copyright History and the Future: What’s Culture Got To Do With It?’ (2000) Journal of Copyright Society of the USA 209, 235; B Fitzgerald et al, Internet and E Commerce Law: Technology, Law and Policy (2007) Ch 4; K Giles, ‘Mind the Gap: Parody and Moral Rights’ (2005) 18 Australian Intellectual Property Law Bulleting 69; W Fisher, ‘Property and Contract on the Internet’ (1999) 73 Chicago-Kent Law Review 1203; Copyright Law Review Committee, Simplification of the Copyright Act: Part 2 (1999) <http://www.clrc.gov.au/agd/www/Clrhome.nsf/HeadingPagesDisplay/Past+Inquiries?OpenDocument> at 25 January 2008; Z Chafee, ‘Reflections on the Law of Copyright’ Parts I and II (1945) 45 Columbia Law Review, 503, 719.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/SydUPLawBk/2008/15.html