University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

MICHAEL J WHINCOP[*]

Accountability is a word often heard today, in both public and corporate affairs.[1] Virtually every delegate of power or funds — from politicians, to chief executives, to grantees of research funds — must justify for the future the continuation of that delegation, and for the past the manner in which that power was used or those funds applied. In a sense, the concept of accountability is politically transcendent. Whereas efficiency has a colour most often associated with the right, and empowerment or equity with the left, accountability is a concept that neither conservatives nor left-liberals seem to dissent from.[2] If we accept that whatever the goal, it is best that those in pursuit be required to give an account of the outcomes of pursuing that goal, it seems to follow that we will prefer the institutions and governance devices that deliver accountability to whichever constituencies should be entitled to it.

In this article, I explain why the concept of accountability must be used with discrimination in real world situations which involve what might be described as multiple agency relations: where agents lack a single principal but instead have moral, legal or political obligations to two or more constituencies whose interests diverge in some respects.[3] This theme is pursued in the context of the devolution of government functions to government corporations (‘GCs’).[4]

Corporatisation — the transformation of state-owned enterprises into incorporated businesses, owned by, but operating substantially independently of the state — has been an important part of the microeconomic reform of the delivery of public goods and the provision of public services in Australia and elsewhere. In today’s political climate, governments are accountable for maximising welfare from the provision of services for a given level of taxation.[5] In discharging this accountability, exploiting the capabilities of competitive markets has much promise, given their general equilibrium properties under certain relatively robust assumptions. This lends support for an environment that is competitively neutral between private and government service providers.[6] That, in turn, demands that government service providers adopt organisational, management and governance structures which will maximise efficiency. This explains the momentum towards corporatisation, amongst other reforms.

However, the concerns that justify the original location of service provision in the public sector are not so easily laid to rest. There remains a tension between efficiency and accountability, apparent in two manifestations. Firstly, it is uncertain how public law controls apply to the corporatised entity and to those in the public sector, such as ministers, with potential power over the entity.[7] Secondly, there is an increasingly conspicuous display of legal ingenuity demonstrating how rules and regimes, characteristic of private law, can apply to entities in the public sector.[8] In addressing these issues, Paul Finn has been one of the most fecund minds in Australia, emphasising the equitable concept of a ‘public’ trust binding government.[9] Another approach — which is, in a sense, bundled with the use of the corporate form by the GC — is to use fiduciary duties to create obligations for the officers of corporations entrusted with the performance of government functions. In this article, I focus on the implications of this latter solution.

On its face, imposing fiduciary duties on the officers of GCs seems natural and logical.[10] The hiatuses that attend the application of administrative and constitutional law to corporate entities demand some form of accountability solution for those who wield considerable power with a public locus. I argue, however, that fiduciary duties may not be the best accountability solution in this context. The fiduciary concept describes a set of obligations owed by the fiduciary to some beneficiary. This addresses the ‘accountability issues’ arising from the power that the fiduciary has, which may be exercised to the disadvantage of the beneficiary. However, these issues are qualitatively different from the accountability issues associated with the government’s delivery of some of its services through a corporate entity. I maintain that the accountability issues here are actually incompatible in many situations, if we accept that the delivery of these services may be affected by rent-seeking in the political process.[11] As an obvious example, when officers are appointed to a GC’s board to represent community interests, or to advance a case on behalf of these interests, conflict of interest considerations inevitably arise between the demands of the interest group and of the corporation (and, arguably, of the welfare of the people). This problem is pervasive and not easily solved. The private law means of addressing it — such as ex ante contracts to address the procedure for resolving the conflict, ex post ratification by a majority of shareholders, or differentiated legal principle applying to nominee directors — are distinctly unappealing from a public choice perspective.[12] Thus, whenever accountability to the people runs the risk of becoming accountability to some group of the people, fiduciary duties can be strained beyond their practical utility. In these conditions, less accountability may be preferred to more.

Part II of this paper examines the nature of the fiduciary duty as it has developed in corporate law. I then describe how changes to aspects of corporate management, such as the takeover and the continuing development of law on nominee directors, prompted certain changes to the strict concept of fiduciary duty known to courts of equity. Part III explores the nature of the accountability concept in GCs. In this section, I develop the concept of the multiple agency relationship and discuss its effect on the concept of fiduciary duty. I contrast two concepts of accountability within a GC: representational accountability and ethical accountability. These spring from two opposed conceptions of the GC and the roles that rent-seeking and political self-seeking play. Part IV examines how the fiduciary duty, both in its strict and more modernised forms, might be applied to GCs. I discuss the fundamental problems that these legal concepts raise and whether we should embrace the representational or ethical variety of accountability. Parts III and IV shed light on these issues by providing some empirical survey evidence derived from a sample of directors of Queensland Government GCs. Part V concludes by pressing the claim that we need to develop better governance mechanisms for GCs, tailored to reflect the differences between the GC and the business corporation (‘BC’).

The fiduciary duty is an old doctrinal concept, which was perfected in English jurisprudence in the development of trust law by courts of equity.[13] The concept expanded into a range of areas involving similar concerns, such as principal– agent, corporation–director and partner–partner relationships. Broadly speaking, the fiduciary duty is directed at moral hazard problems. Moral hazard problems involve actions, taken by a party empowered or financed to undertake some task, that reduce the welfare of the person conferring the power or finance.[14] They are problematic because they are difficult for the entrustor to observe, which limits the capacity to bargain and strike the first-best contract between the two parties.

Historically, fiduciary duty was a concept applied almost exclusively to private law relations. Despite some similarities in the types of opportunism a political agent and a fiduciary might engage in, the law developed different means to address political self-seeking. Only recently have scholars addressed the fiduciary duties of government and the possibility of a ‘trust’ of powers conferred by people to politicians.[15] Some of the reasons for this historic conservatism will become apparent in this article, but I want to make one point here that explains the pragmatism of this much-maligned ‘public–private divide’.

Fiduciary duties mandate a standard of selflessness in the advancement of the interests of the beneficiaries.[16] The ease with which such a standard can be administered depends on various factors. These include the number of beneficiaries,[17] the homogeneity of their interests,[18] the complexity of the required management tasks,[19] and the extent of distributive discretions.[20] Thus, amongst fiduciary relations, the publicly listed BC is one of the hardest contexts in which to apply the duty because determining the care taken in managerial tasks is difficult for courts to assess (reflected in traditionally low standards of care). On the other hand, it is simplified somewhat by the homogeneity of interests (all shareholders want value maximisation, especially where the costs of trading shares are low)[21] and minimal distributive discretion as between shareholders.[22] The other traditionally difficult context for applying the equitable fiduciary duty is the charitable trust, given the imprecise specification of beneficiaries by reference to purposes, not persons. Equity compensated by public enforcement and a close insistence on charitable purposes.[23]

Governmental contexts are vastly more complex than these relations. Distributional considerations are practically unlimited given the tolerance for redistribution and subsidisation in modern society. Further, the interests of the public are anything but homogeneous. Combined with distributional flexibility, these considerations provide scope for rent-seeking by interest groups. Thus the opportunity arises for politicians to gain by catering to these demands, if a rule requires less than unanimity for collective action.[24] Finally, politicians and senior political appointments in the public service are hard to judge by a standard of selflessness because they are not empowered by a process of consent, as is true of the trustee’s appointment by a settlor, but by majority choice made on the basis of competing platforms varying as to both ends and means.[25] Together, these factors contribute somewhat to explaining the historical reluctance to apply the fiduciary concept in the public sector.

The fiduciary duty is not immutable. Its application has changed with the increasingly complex environment in which directors must make decisions. In the following three sections, I review the traditional and modern conceptions of the fiduciary duty. These will be revisited in Part IV where I examine the capacity of these conceptions to deliver accountability in GCs.

Traditionally, and still at least ostensibly, fiduciary duties in BCs applied in a manner hardly differentiated from the paradigm obligation of the trustee. Perhaps the oldest and most cited exposition of the concept in Anglo-Australian corporate law is provided in Aberdeen Railway Co v Blaikie Bros.[26] Lord Cranworth LC said there that

no one, having [fiduciary] duties to discharge, shall be allowed to enter into engagements in which he has, or can have, a personal interest conflicting, or which possibly may conflict, with the interests of those whom he is bound to protect.

So strictly is this principle adhered to, that no question is allowed to be raised as to the fairness or unfairness of the contract so entered into.[27]

From an analytical perspective, this duty has two components. One is a flexible approach to the conflicts of interest that invoke the rule. The concept is imprecise, even protean.[28] The other, contrasting component is an inflexible approach to the application of the rule. Once a conflict of interest exists, the rule is applied independently of intentions, knowledge, or effects. The paradigm transactions that breach such rules are where the director is a party to a contract with the firm, or where the director has interests in such a party, whether as an officer or as a shareholder.

Although this rule was inflexible in its application, it was not immutable in its content or consequences. The fiduciary rule did not insist that a director could never contract with their firm. It contemplated two permissible ways by which such transactions might be validated. These may be contrasted as ‘ex ante’ and ‘ex post’ approaches. An ex ante approach involved using contracts to modify or exclude aspects of the fiduciary duty prohibiting conflicts. Empirical evidence confirms that it was far more common for publicly listed corporations to modify the fiduciary duty in some respect than to retain it in its strict form.[29] This was done by including provisions in the articles of association. These usually permitted transactions in which the director was interested, provided the director declared the nature of their interest to the board, or abstained from voting, or both.[30] Influenced by the ideas of a laissez-faire political economy, 19th century courts regarded parties as competent to waive the benefits of such a rule.[31]

The ex post approach regarded the shareholders (by majority) as being competent to waive their rights under the conflict rule in relation to a specific transaction.[32] This process of waiver or ratification had certain procedural requirements, such as the fiduciaries being expected to make full disclosure, and the transaction not being coercive.

These principles were in many ways a product of the times in which modern company law emerged. In the second half of 1 9th century and the early 20th century, English companies were small and characterised by concentrated ownership and family involvement.[33] The fiduciary duty provided protection against the main forms of moral hazard, while permitting smaller bodies of shareholders the opportunities to opt between the traditional rule and the contractual alternatives. The extant case law of this time otherwise demanded relatively little formal legal accountability for a director’s actions or omissions.[34] The next section shows how these principles changed in the 20th century to accommodate developments such as the hostile takeover and the emergence of nominee directors.

B The Modern Concept 1 Improper Purposes

Although the precise time of the change is disputed, corporations and the financial markets in which they raised finance and in which their securities were traded changed markedly in the late 20th century. Ownership concentration in the 20th century became increasingly diffused.[35] The decreased transaction costs associated with capital raising eventually led to the advent of the hostile takeover, and this put directors in a position of having to decide how to respond to a bid for the outstanding equity.

In general, hostile takeovers are unwelcome phenomena for incumbent management because, if they succeed, they spell dismissal. In the absence of legal constraints or other incentives responding to this problem, management will often attempt to foil the takeover. However, it is not clear in every case whether such defensive action is contrary to the best interests of shareholders. There are two reasons for this. First, some scope for defensive action may provide the conditions necessary for senior management to make sunk cost, firm-specific investments of their human capital, which will in turn benefit the shareholders.[36] Such investments may not be made if those managers are in danger of being denied access to the assets to which their human capital is specific subsequent to a takeover.[37] Second, defensive action may facilitate an auction for control, which increases the price that shareholders receive, and may increase allocative efficiency if the highest bidder puts the target’s assets to best use.[38] It is unclear whether the higher takeover premiums occurring in auctions are offset by the disadvantage to shareholders that bids, being more costly, are less likely.[39]

It is in this ambiguous environment that courts had to adjudicate the validity of defensive action in response to hostile takeovers, in light of the fiduciary duty. Across common law jurisdictions, the outcomes have not been consistent. Whereas English courts have insisted on a strict, inflexible approach in which there is no scope for defence,[40] Australian[41] and American[42] courts have upheld defences to takeovers on various occasions.

My present focus is on the Australian approach. Courts commenting on these adjudications assert that the principles they apply are fiduciary.[43] It should follow that courts should not permit defence, since defensive actions are, in the language of Aberdeen Railway Co v Blaikie Bros, ‘engagements’ in which directors have ‘a personal interest conflicting, or which possibly may conflict, with the interests of those whom [they are] bound to protect’.[44] Since courts do not investigate ‘fairness’ — which would include the justifications for defence — the argument in favour of an auction, for example, would seem to die stillborn, at least in the absence of either an ex ante contract permitting bidder dilution[45] or ex post ratification.[46]

Yet that is not the case. In some instances, Australian courts have upheld takeover defences as not infringing fiduciary obligations. In doing so, they have refined the fiduciary principle applying in these areas, consolidating it under the rubric of ‘proper purposes’.[47] Directors must act for proper purposes. Courts decide these cases by posing a counterfactual causation test. Unlike the strict test, where it was only necessary to ask whether a conflict existed, the law in this area asks whether, but for an improper purpose (such as entrenchment), the directors would not have acted as they did.[48] The existence of an ‘incidental’ advantage does not invalidate the action.[49] Such a test requires scrutiny to determine that some management justifications for the action exist, even if the justifications themselves are not reviewed on the merits.[50]

Although courts have been remarkably reticent in acknowledging it, they have changed the fiduciary principle fundamentally in its application to takeovers and similar events such as proxy fights. There is, however, no suggestion that the traditional law no longer applies to cases that involve more conventional forms of overreaching. Why then have courts made this differentiation? Perhaps one reason lies in the fact that, unlike conventional forms of overreaching, directors do not directly bring takeovers onto themselves; they are respondents, not initiators.[51] In that sense, the moral hazard problem is not quite as pressing. Another reason may lie in the ambiguous nature of the optimal scope for defence.

Another development in modern law is the modification of the fiduciary principle to accommodate the nominee director.[52] A nominee director is typically appointed to the board as part of some contractual arrangement between a party, such as a major investor, and the corporation.[53] The question therefore arises as to the circumstances in which the nominee may legitimately act in the interests of their nominator, if they are bound by fiduciary obligations.

Although the actions of nominee directors have sometimes been quite controversial,[54] the law has generally recognised the entitlement of such directors to further the interests of the nominator.[55] An example is where directors take action to enforce a security granted by the company to the person nominating them.[56] The inconsistency with the traditional approach has been acknowledged, but justified in the name of ‘commercial practice’.[57]

In a sense, the nominee director is another example of an ex ante contract varying fiduciary obligations. The entitlement of the nominee to protect the interests of the nominator, rather than abstaining from any relationship with a nominator that could possibly conflict with the interests of the corporation, is part of a larger transaction which presumably benefits the corporation.

This part explores the nature of the accountability concept in GCs. It begins with an exposition of the various ways in which accountability relations may be formulated in a GC, explored further through an empirical study. The second section examines the concept of the multiple agency relationship and discusses its effect on the fiduciary duty. Two problems are highlighted — one of commensurability and one of rent-seeking. The third section examines the implications of rent-seeking for accountability, contrasting two concepts of accountability in a GC — representational accountability and ethical accountability. It suggests the impossibility of satisfying both accountability concepts simultaneously.

In the first section of this part a range of alternatives in formulating the accountability relationships in GCs are compared. The second section describes the results of a survey of GC directors, which sheds some light on directors’ conceptualisations of the character of their accountability relations.

In the standard corporation it is common to formulate the central accountability problem in terms of an agency relationship between managers and shareholders.[58] Accountability runs from the former to the latter. However, the accountability relationships in GCs are more numerous and more complex. Managers continue to be agents, but they are not the only agents. Ministers, who hold shares, and are responsible for the governance of the corporation, issuing directives to it, and making other determinations of policy affecting it, must also discharge an agent-like responsibility — albeit one located in a political context.

The question remains as to who is the principal of each of these agents. If we treat shareholders of a BC as the principal of the agent–managers, there is an analogical case for treating the minister as the principal of the managers, since the minister is typically the shareholder in a GC.[59] This has the advantage of making the translation from BC to GC as smooth as possible. However, this option is complicated by the minister’s status as a political agent with predictably partisan inclinations. It concentrates political power in the minister, when the BC is supposedly used in order to liberate the business enterprise from such involvement, and to extricate it from the environmental inefficiencies of the bureaucracy.[60]

We might take a citizenship approach and conceive the principal as being the ‘people’ — the state ‘as a whole’ is the ultimate principal.[61] This is appropriate in the sense that it is the people as a whole who benefit from good governmental ownership, and this approach avoids the need to pick and choose amongst citizens on the basis that some subset of the people are more affected or more deserving than others. This citizenship option is often implicit in much of the property rights analysis of government ownership — problems of government ownership are attributed to the extreme diffusion of such ownership interests and consequent problems of collective action.[62] However, this is an agency relationship of the weakest kind, since the principal lacks any formal empowerment, and has no powers or control of any kind in relation to the agent.[63] The minister might similarly be cast as agent to the people as principal, but the same criticisms apply here, too.

Alternatively, we might take a responsible government approach and say that the real principal of management, and of the minister, is Parliament.[64] Applied to the minister, this fits with the Westminster system of government.[65] Indeed, the notion that management is accountable to a minister who in turn is accountable to Parliament — the members of which are elected by the people — is probably the most intuitive set of accountabilities for GCs.[66] However, while there may indeed be such a chain of connections, the management of a GC is not directly accountable to Parliament, unless it specifically chooses to legislate to that effect. Consider, for example, the following comments:

if the Corporatisation legislation established … a company and charged its Board with the responsibility for its administration and management, the relevant Minister could not properly be held responsible for management. To the extent that the legislation would give the Minister the power to set policy directions for the particular corporatised GOE — for example, in negotiating or approving the annual performance contract or requiring Community Service Obligations to be undertaken — the Minister would be responsible for that area. … But Ministers would not be responsible for day-to-day management decisions. In short, one of the features of Corporatisation legislation would be to make Ministers accountable to Parliament as investors in GOEs, not as their managers.[67]

Corporatisation is therefore intended to create a new dynamic in the interaction between the minister and the bureaucratic enterprise. For instance, new questions arise regarding ministerial influence, which falls short of any constitutionally recognised form of executive control, but which is analogous to the power wielded by institutional shareholders in BCs.[68]

A fourth possibility might be described as a stakeholder approach, which treats the management of the GC and the responsible minister as accountable to, or the agent of, the principal users and interest groups.[69] It is therefore a more selective version of the citizenship approach. Stakeholder models of accountability have been much advocated in recent years. The notion that it is desirable to empower the constituencies affected by organisations is communitarian, and runs counter to the narrower, dyadic agency relationships favoured by economists.[70] A stakeholder approach may be especially desirable in GCs, which administer natural monopolies, and thus are not subject to competitive market protections. On the other hand, empowering stakeholders runs the gauntlet of interest group capture.

The final possibility we might label as an entity approach. It is common for Anglo-Australian authorities to describe fiduciaries as owing duties to the corporation to act in its best interests.[71] There is a lively debate concerning the appropriateness of reifying the entity, since economists, relying on their premise of methodological individualism, assert that corporations have no meaningful existence of their own.[72] However, reification may have instrumental value. That is, a duty to the corporation might be treated as a duty to maximise the value of the corporation’s assets.[73] Such a principle can be used for GCs as well, assuming value maximisation is an appropriate objective. It is difficult to know how this obligation would be placed if the corporation embraces non-efficiency objectives, such as distribution. Also, situating accountability inside the corporation can result in a hiatus of accountability for both managers and ministers, especially since the absence of an external beneficiary can diminish the number of persons with standing to enforce the obligation.

To conclude, the accountability relationships that have been identified all have some points in their favour. Indeed, it is surely an aspirational standard for ministers and managers to attempt to act in the interests of all of those posited — the people, Parliament, user groups and business. However, the problem is that in the absence of one of these explicitly dominating the others, these multiple agency relationships generate conflicts.[74] A measure designed to protect one set of principals can diminish accountability to the others. This is especially difficult because the two most intuitively preferred choices — management to the minister, and the minister to Parliament — both identify a principal who is clearly an agent. This in turn begs a further question about which set of interests should give substance to theirs.

In order to shed some light on the issues probed in the last section, a survey of GC directors was undertaken to learn what they thought the structure of their accountabilities actually were. This formed part of a larger project undertaken with Queensland Treasury, investigating the corporate governance arrangements in GCs. Consequently, the survey, in the form of a structured written questionnaire, was targeted at directors of all entities falling under the Government Owned Corporations Act 1993 (Qld). This constraint may have imposed a selection bias on the results, but it is also likely to have assisted in boosting the response rate compared to a ‘cold call’ survey.

Table 1 summarises the population of the directors, the number of directors whom we were able to send surveys to, and the reasons why directors could not be reached in the other cases. Table 2 summarises the breakdown of present and past directors and information about the GCs they came from. For reasons of confidentiality, the three ministerial portfolios that the GCs fall within have not been specifically identified. Instead, they are simply referred to as Portfolio A, Portfolio B, and Portfolio C.

TABLE 1: POPULATION AND SAMPLE

|

Directors identified as serving or having served on Queensland GCs

|

307

|

|

Number of deceased directors

|

4

|

|

Maximum possible respondents

|

303

|

|

Directors for whom addresses were not found

|

13

|

|

Surveys ‘returned to sender’ for wrong addresses

|

7

|

|

Maximum possible responses

|

283

|

|

Number of completed surveys

|

121

|

TABLE 2: CHARACTERISTICS OF SAMPLE

|

|

Past

directors

|

Current

directors

|

Total

|

|

Portfolio A

Portfolio B

Portfolio C

|

32

28

6

|

22

24

9

|

54

52

15

|

|

Total

|

66

|

55

|

121

|

The survey instrument asked directors to select the best response to the following statement:

I anticipated that my duty as a director would be to:

(a) Maximise the value of the corporation;

(b) Act according to the interests and wishes of the minister;

(c) Serve the interests of the constituency I was to represent;

(d) Serve the interests of the people of Queensland as a whole;

(e) Reconcile the conflicting demands and interests as to how the GC should be

managed.

The answers are summarised in Table 3.

TABLE 3: PERCEPTIONS OF DIRECTORS’ DUTIES

|

|

%

|

|

Maximise the value of the corporation

|

51.3

|

|

Act according to the interests and wishes of the minister

|

2.5

|

|

Serve the interests of the constituency I was to represent

|

8.4

|

|

Serve the interests of the people of Queensland as a whole

|

28.6

|

|

Reconcile conflicting demands

|

9.2

|

|

Total

|

100.0

|

It seems clear that the accountability relations in GCs are by no means precise, since there is some support for each formulation. The strong support for the first formulation (which derives from the entity approach to accountability) and the somewhat weaker support for the fourth formulation (corresponding to the citizenship approach) are significant, in that both of these are the most indefinite in recognising a specific beneficiary. The entity approach does not identify a meaningful beneficiary at all, and the citizenship approach specifies beneficiaries with extreme generality. This may reflect the imprecise accountabilities of the GC’s multiple agency relations. Nonetheless, 17.6 per cent of directors saw themselves as either representing a constituency or negotiating between them.

It is evident that a GC is characterised by multiple agency relationships. Consider an example where the GC must determine the price for its services. On one hand, the interests of the people and the ‘corporation’ are served by pricing that maximises the surplus of revenue over costs, but the interests of users and stakeholders may be best served by quite different policies. The usual method designed to address this problem in the corporatisation process — the community service obligation (‘CSO’) — does not eliminate the problem.[75] A minister of a portfolio department will be under pressure to maximise returns from expenditures in their departmental budget, and will therefore exert influence on the GC not to discontinue the provision of particular services, since they would then be responsible for paying for it specifically.[76] There are obvious risks of strategic behaviour in these areas — especially where the GC has a monopoly.

To some extent, multiple agency relationships also affect BCs. These arise when the interests of shareholders diverge. Ordinarily, shareholders have common incentives; capital markets assist in the cultivation of optimal risk preferences in the case of listed companies. However, a takeover can reduce this homogeneity. Here, the interests of one shareholder, the bidder, may be imperfectly aligned with the interests of other shareholders, particularly in respect of the procurement of another competitive bid.

There are several reasons why divergence in the BC is less problematic than the multiple agency relations of the GC. Except during the pendency of a contest for control, the interests of the bidder and the interests of the target shareholders are well-aligned — both want the agents to maximise the value of the corporation.[77] Moreover, takeovers demonstrably increase the social welfare of shareholders.[78] The problems identified with takeovers in the literature are associated with interests other than those of shareholders, such as managers making firm-specific investments. In a sense, the problem here is epistemic — there is a question of what we are capable of knowing about the interests of the constituency whose interests are undoubtedly intended to be sovereign.

The GC is different in several respects. First, there is no reason to think that alignment between interests constitutes the norm, rather than the exception, as in BCs. This is exemplified by the pervasion of non-efficiency norms in GCs. In particular, the people as a whole may favour efficiency as a norm of social choice, but users as a subset of the people and the interest groups acting on their behalf may favour distributive considerations and other intangible goals, such as regional development. There is no easy means to resolve these different preferences, since the interests pressing these diverging claims are not mediated by a market mechanism requiring a willingness to pay the opportunity cost for them, as is the case in the BC.[79] Further, in addition to the epistemic problem, there is no compelling normative or ethical basis for choosing between these groups.

This gives rise to two particular problems. Firstly, accountability is compromised by the difficulties associated with measuring progress towards non-efficiency goals. This is a commensurability problem.[80] For example, the New South Wales corporatisation legislation states that the objectives of the entity are, amongst others, to maximise the net worth of the State’s investment in the corporation and to exhibit a sense of responsibility towards regional development,[81] and that each of these is equally important.[82]

Secondly, the means which GCs adopt to try to balance conflicting demands are likely to be influenced by the political activity of the interest groups of users. The preferences of interest groups are unlikely to align with the calculus of social welfare. This is a rent-seeking problem.[83] The rent-seeking problem is in part exacerbated by the commensurability problem. If progress towards non-efficiency goals was more clearly measurable, the capacity of interest groups to engage in rent-seeking would potentially be diminished, since it would be more apparent when servicing their interests occurred to the detriment of society.

Rent-seeking is a pervasive problem in politics, which enters into GCs by virtue of the existence of multiple agency relations and the commensurability problem. However, it is worthwhile to consider the relation between rent-seeking and the GC. In countries such as Australia, the corporatisation phenomenon of converting statutory authorities into GCs has been advocated as a measure of increasing efficiency in the delivery of government services.[84] However, it is by no means self-evident why politicians would want to increase efficiency, at least where it comes at the expense of the capacity to satisfy the preferences of effective interest groups.[85] This might occur, for example, where a utility sets prices equal to marginal cost — it is prima facie efficient to price in that way, but it may be at odds with the preferences of, for example, rural or consumer interest groups.

Two very different approaches to the relationship between rent-seeking and GCs are possible. On one hand, the GC may cause the costs of rent-seeking to rise, in so far as it is a means of tying the hands of politicians, restricting their capacity to satisfy the demands of interest groups. A diminished scope to determine which services are provided, or at what price, should raise rent-seeking costs. The minister will find it harder to influence the provision of services that the interest groups demand, and must use more public and visible means of influencing these matters, such as the CSO process (which decreases the information costs and thus increases the effectiveness of those who would oppose the measure). Such a theory presumably also requires that interest groups find it difficult to lobby those who are responsible for management decisions, since ministers will be less responsible for these matters.

On the other hand, it is possible that the use of GCs may actually be a means of facilitating rent-seeking, by decreasing its cost. This may occur by relocating the provision of services from a political context to a corporate one. This frees it from the usual controls associated with executive action, such as judicial review and freedom of information, and perhaps also from the constraints associated with existing government commitments (including ideological ones). The board’s interactions with interest groups and the minister are less structured and less visible. The lower costs of rent-seeking need not be unequivocally negative — they may encourage greater competition for rents between interest groups and thus minimise the deadweight costs of particular deals.[86]

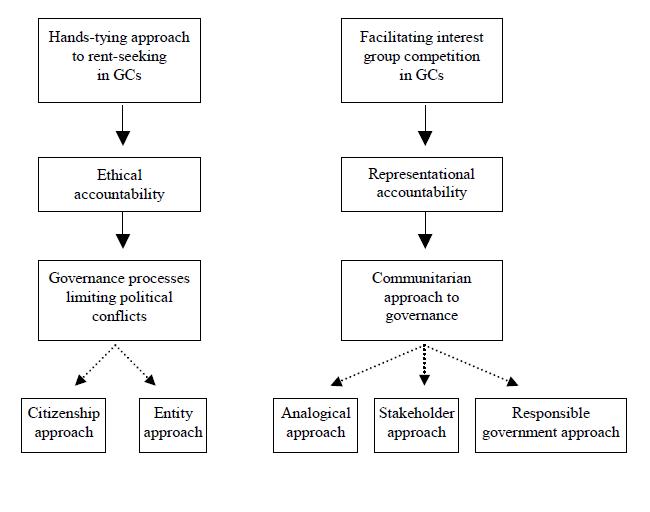

It is these ambiguities of a GC’s relation to rent-seeking that create serious doubts about which accountabilities should invest the governance of the GC. In turn, this creates doubt about the wisdom of borrowing governance concepts from corporate law, as explored below in Part IV. Considering the accountability question first, these two divergent conceptions of the GC suggest two very different concepts of accountability, which form the more fundamental distinction from which my earlier identifications of specific accountability relations flow.

The first may be described as a representational version of accountability. In this view, governance mechanisms are evaluated according to their capacity to require those with control to faithfully represent stakeholders and interest groups. The representational version of accountability fits the second account of the rent-seeking role in the GC, and includes the analogical, responsible government and stakeholder constructions of the accountability relationships. Since the emphasis is on removing restrictions to rent-seeking, governance will be marked by ministerial involvement in strategic planning and governance processes, and the development of channels which permit lobbying.

The second version of accountability is very different. It may be called an ethical version since it evaluates governance mechanisms according to their ability to restrain the capacity of those in control to further their own interests or those of rent-seeking constituencies. This is built around the first conception of the GC in which the scope for rent-seeking is diminished. It might be viewed as linking to the citizenship and entity constructions of management’s accountability relationship. This is a more straightforward focus on efficiency, which consigns distributional and communitarian considerations to the legislative process. I describe it as an ethical version since it demands that those in control of governance processes abstain from functioning as the advocates of interest groups as a matter of deontological obligation, irrespective of the justifications for doing so. Such a version of accountability may decrease the influence of rent-seeking on the governance of the GC, but it will also diminish accountability in its representational sense. It depends on the existence of measures that create positive incentives for those in control of management processes to maximise efficiency, since diminishing the scope for representational accountability does not in itself increase the identification of those persons with social welfare concerns, nor the incentives to perform. An ethical accountability also effectively presupposes the nature of the interests of the people, except in any respects where these are embodied in legislation. It is therefore neither a responsive nor a representative approach.[87]

Translating these versions of GC accountability into prescriptions for management and ministers leads to predictably antithetical results. The representational prescriptions for managers are that directors, chief executives and others should be accessible to advocacy and act in a communitarian manner. Ministers should be willing to use their influence over the board in order to further the concerns of their constituencies. This can occur in a number of ways. It might include appointing persons to the board who can function as community advocates. Alternatively, the minister can use their direct influence over the board in ways designed to encourage particular investment or pricing decisions. The CSO has a somewhat equivocal role in representational accountability. On one hand, one would expect to see the GC adopt more CSOs. On the other hand, the board and the CEO would be encouraged to pursue particular courses in the interests of stakeholders without the need for the formal imposition and pricing of the CSO.

The ethical prescriptions are naturally very different. The ethical version of accountability strongly discourages community appointments to the board or to executive positions and encourages a high level of independence from community interests amongst directors. The role for ministers is somewhat more complex. It does not necessarily require passivity, in the sense that they must abstain from exercising influence over the board. Ministers could encourage boards to maximise efficiency. The challenge is how to permit ministers to exercise some forms of influence (those increasing social welfare) but not others. Increasing the public visibility of board–minister interactions and requiring increased credibility in commitments to ex ante performance goals may be ways of addressing this problem. It may also require that governments ensure that the area in which the GC provides services is as liberalised and contestable as possible, in order to enhance competitive pressure on both the GC and minister, and to expose the existence of subsidies implicit in contracts for the provision of services.[88]

Figure 1 demonstrates a schematised relation between the conception of GCs, accountability and governance.

I have described ethical and representational accountabilities in somewhat idealised terms. The experience in most GCs, perhaps inevitably, shares elements of both. My argument is not that this is inappropriate, but to emphasise two ideas. First, this demonstrates the impossibility of fully satisfying both accountability concepts simultaneously, as has been argued in Part III. Second, it lays the framework for demonstrating the functional problems in applying fiduciary duties to GCs. This point is developed in Part IV.

FIGURE 1: RELATION BETWEEN CONCEPTIONS OF GCS, ACCOUNTABILITY AND GOVERNANCE

This section reveals some of the problems associated with the application of fiduciary duties, in both traditional and more modern forms, to the directors and senior executives of GCs. It should be noted at the outset that the fiduciary duty could still have meaningful application to traditional forms of overreaching, such as interested contracts, misappropriation, breach of confidence, and diversion of business opportunities. These affect GCs in much the same way as they affect any BC and are not substantially affected by changing the posited ‘principal’.

A more interesting question is how the traditional means of relaxing the fiduciary standard or validating a fiduciary breach may be applied to GCs. There is no reason why GCs should not be able to develop their own principles applicable to, for example, self-dealing concerns. These might be influenced, among other things, by practice in relation to public accounts. They could be embedded in the company constitution, with the generic GC legislation enacted by the States deferring to more specific schema developed for the GC.[89] The constitution could be amended and updated on the recommendation of the board of directors to the Governor-in-council. The Governor-in-council is a more logical choice than the relevant minister. Questions about changes of governance require a somewhat broader constituency whose deliberations and determinations are visible, without imposing the more costly and less flexible precondition of amending legislation. The following sections explore the conflicts of interest which are raised by the relation between directors and CEOs, and interest groups.

One of the inherent difficulties associated with applying fiduciary duties to political conflicts lies in the imprecise nature of payoffs in the political process. A director in a BC who has entered into a contract with the company, or is a shareholder in another corporation with such a contract, has the opportunity to profit from the performance of the contract. A GC director, who acts as an advocate for a particular constituency may receive nothing directly from their advocacy of a particular issue. The payoffs are likely to be indirect, such as increased opportunities to act for the group in the future (including as a director), access to greater political patronage and reputational advantages. These benefits are not conferred under agreements binding in any legal sense — in part, because of difficulties in verifying faithful political service and the unwillingness to scrutinise the nature of the deal — but according to the social norms to which group members subscribe. It would be hard to demonstrate to a court’s satisfaction the nature of these processes. In addition, as shown in Part III(B) above, to the extent that GCs internalise non-efficiency goals, it becomes harder to condemn activities having a redistributive effect that would typically be struck down as contrary to the best interests of a BC.[90]

These factors indicate that there will be difficulty identifying conflicts of interest of a political nature. The court would be implicated in a range of complex politically charged issues. These include the durability of connections between directors and interest groups, the political support or other payoffs the director might expect for undertaking a lobbying function, the social welfare justifications of the particular resolution taken, the worth of any alternatives that the decision caused the GC to forego, and the means by which interest groups could lobby the GC in the absence of specific advocacy by a particular director. Courts have long avoided such intensely political judgments, but under the application of a strict fiduciary concept they seem inevitable — unless the interests of the corporation are to be given a ‘concertina-file’ definition, which expands so that no political conflict or indulgence of rent-seeking ever lies outside it.[91] Identification of political conflicts is thus greatly complex under the demanding traditional standard.

Once a conflict is identified, the application of the requirements of equity is even harder. Although it is quite easy to rescind an interested contract, determining how to restore the status quo ante in the context of a political conflict in a GC is fraught with peril. How can a court require a pricing policy, for example, to be rescinded without itself determining prices? Rescinding capital works, after costs are sunk, is even harder. Moreover, there is no easy set of substitute remedies, such as the constructive trust or equitable compensation. One can imagine the controversy that would be caused if an interest group was ordered to hold the wealth transferred to it on constructive trust for the GC. The director rarely makes profits that equity could seize on and the determination of loss is perverted by the possible presence of public good considerations. The only sanctions that can be used are disqualifying the director from continuing in office or holding GC actions to be ultra vires.[92] The corresponding procedural question is who would be entitled to seek judicial review of the political conflict.[93] A wide definition of standing would allow the losers from political deals to contest the deal in the courts, thus increasing the politicisation of the judicial function. A narrow definition would concentrate political power.

The usual means of validating a conflict also raise difficulties: how might a political conflict be ratified; and who would ratify it? Having regard to orthodox doctrine, the power would normally be conferred on the minister.[94] Giving the minister that power would afford them an ‘auctioneering’ role with respect to rent-seeking. That is, they would be the final arbiter of which interest groups succeeded in their redistributive aspirations with respect to the GC, but without any of the usual political controls applying in public law, beyond answering to Parliament. Such a measure would be fatal to an ethical accountability owed by management and the minister.

How might a strict fiduciary standard be relaxed ex ante for the purposes of political conflicts? In a BC, the concern that a relaxed standard might lead to increased overreaching may encourage shareholders to pay less for the shares,[95] and so the offeror of the shares pays for any expected increase in overreaching. Thus, only wealth maximising alterations appear likely. There is no similar pricing process in GCs. Therefore, society as a whole would bear the costs of a more liberalised process for rent-seeking in GCs, and well-organised interest groups would bear the benefits. The likelihood of only wealth maximising alterations would also disappear.

All that can be said of the strict concept is that it reflects quite well the ethical accountability concept described above. In particular, it would encourage governments to make appointments of independent directors to boards, which might enhance the capacity of the GC to reduce rent-seeking. However, this depends on the capacity of the board to be insulated from equivalent pressures from the minister, and the selection of directors who are unlikely to seek political favour even in the absence of direct lobbying. We have also seen that to the extent that a strict duty requires increased ratification from the minister, it may actually decrease ethical accountability by concentrating political power in ministerial hands.

Part II described how courts adapted the application of fiduciary duties in response to the emergence of the takeover. The strict version of the fiduciary duty would mandate an extreme passivity on the part of directors which may diminish the scope for competitive auctioning of control and for the protection of firm-specific investments of human capital by managers and employees. The weaker variation of the fiduciary duty reflected the fact that directors do not initiate takeovers, unlike most of the other actions triggering fiduciary duties. The question is whether this version of the fiduciary principle, with its emphasis on improper purposes, may be a more appropriate way of addressing political conflicts in GCs.

The use of improper purposes fits quite well with the representational version of accountability. Improper purposes inquiry normally emphasises the extent to which directors have identified with collateral purposes. That question of degree represents a useful focus since we may concede that the notion of a wholly disinterested GC director — or at least a wholly disinterested director whom one would actually wish to appoint — is unrealistic. Some degree of receptivity to community concerns is appropriate, if for no other reason than to enhance the flow of information to the board about the effects of GC decisions.

However, applying the test to GCs is very difficult. The first difficulty is determining which interests are actually improper. The pervasion of multiple agency relationships makes it difficult to rule out any constituency as having no claim on the GC. This is unlike a BC where the focus is on the shareholders, or perhaps the business of the corporation. If no constituencies’ interests are improper per se, then under what circumstances could the furtherance of these interests be actionable? One might concede that the furtherance of undisclosed and non-obvious interests might be improper. However, the only other way such a finding could be made would be on the basis that particular interests have been accorded too high a priority, which demands political judgments inimical to the judicial function of a court.

One way by which to judge whether purposes are improper is by means of purposes and objectives which have been officially specified. In Australia, GCs are often required to develop planning documents, called statements of corporate intent (‘SCI’), by negotiation between the board and the minister.[96] Such a process particularly encourages competing interest groups to signal their preferences if advocacy of their interests has not been struck down as inappropriate. However, this approach depends on the integrity of the process by which the SCI is negotiated. The usual process involves the minister and the board, which raises several causes for concern. The first is that, like ratification under the strict duty, it continues to concentrate the power to arbitrate competition in rent-seeking on the minister, if their consent is required for the SCI. It may also encourage various forms of strategic behaviour by the minister since the SCI, in this scheme of things, can become a means by which the minister can pre-commit the board to follow the minister’s mandates. The second might be thought an issue of contract specification. An SCI, like any real world contract, is incomplete in the sense that it can only provide for a matter in a general way, rather than in a manner that is contingent on all the different states the world might take in the future. The future might take a form in which furthering the interests of a particular constituency is highly undesirable.[97] Validating its furtherance because it happens to be specified in the SCI in a general way would then be inefficient. Moreover, the SCI is inferior to any contract, because the promisees (interest groups) are not obligated to pay the cost of the promise. Rather, they need only confer such political support on the board or the minister as suffices to have their interests reflected in the SCI and furthered by the GC.

The improper purposes standard imposes a counterfactual inquiry: but for the allegedly improper purpose would the power have been exercised? This is a complex issue in GCs. Advocacy of particular interests may be carried out by one director or a small number of directors forming less than a majority. Their influence on the decision of the board is difficult to gauge, even where they lack a majority. In the first instance, their capacity to get an issue on to the agenda can be a huge step towards making a desired resolution. Moreover, the incidence of log-rolling between the proponents of different constituencies makes it hard to distinguish between legitimate compromises between users and straightforward political deals which make the GC and the people as a whole worse off.[98]

To conclude, the improper purposes rubric may suit the modern BC as a means of mediating contests for control. However, it is no more suited to the GC than the traditional strict version. In some respects, it is no different from the strict version, since it raises identical concerns as to standing and remedies.

The nominee director represents a second modernisation of the fiduciary concept. It has obvious attractions for the purposes of representational accountability, since it permits constituencies to have direct representation on the GC board without the fear that the fiduciary concept will permit the nominee to consider all interests save their nominator’s.

The law on the nominee director does, however, pose some practical problems. First, it is unclear whether only nominee directors can act in furtherance of the interests of constituencies, while all other directors are bound to a stricter fiduciary principle. Second, it is not apparent how the number and the identity of nominators of nominee directors should be decided. In the BC, this question is simple to answer since it is decided as part of the contract between the corporation and the nominator, with such necessary adjustments to the constitution as are required for the powers and obligations of the board to accommodate this bargain. The matter may be left to contract, since the nominator effectively ‘pays’ for the right to nominate by offering a lower rate of interest, demanding a smaller proportion of the equity, lower wages, or the like. However, in the GC a similar trade does not take place, except as between the political support offered to politicians and the interest group. It may well be desirable to minimise the entitlement of politicians to give away nominee rights, especially if non-nominee directors are disabled from representing other views. Such an arrangement would represent a barrier to entry for interest groups unable to ‘afford’ the right to nominate, which would in turn decrease competition between interest groups.

Compared to the uneasy demand for strict disinterest required by traditional fiduciary duties, the law on nominee directors is, in some respects, a more suitable mutation of the law on fiduciary duties for bodies in which community representation is deemed appropriate. While explicit representation of interest groups on the board is a major step towards a representational accountability, it is also a major step away from ethical accountability. The appropriateness of representational boards, and of how such representational boards should be constituted, is a highly contentious subject that needs explicit justification if it is to avoid locking in the interests of particular groups.

In order to gauge how fiduciary standards might apply to these more government-specific transactions, the survey described in Part III above asked the directors to specify how examples of these transactions would have been handled, and how they should have been handled. For each case, directors were offered four generalised responses as to what the director facing the conflict should do:

(a) The director declares her interest and absents herself from deliberations and the vote;

(b) The director declares her interest and abstains from voting, but is present for deliberation;

(c) The director declares her interest but deliberates and votes;

(d) The director discusses and votes on the issue without reference to any interest.

The three hypothetical conflict situations were:

(1) The GC is deciding whether to provide new services to country regions. The board has an appointee who resides in such an area and often advocates for rural interests.

(2) The board is considering how it will approach the next enterprise bargain. The board includes a director who has been appointed to represent the interests of workers in this and allied industries.

(3) A director has a substantial pecuniary interest in a company which has tendered for a contract being considered by the board.

The results are summarised in Table 4.

TABLE 4: MEANS BY WHICH THE CONFLICT WOULD

AND SHOULD BE HANDLED

|

TRANSACTION

|

Declare,

absent

|

Declare,

deliberate,

abstain

|

Declare,

deliberate

|

No reference

to interest

|

Total

|

|

Country Services

|

28.4%/28.7%

|

35.3%/40.0%

|

23.3%/20.9%

|

12.9%/10.4%

|

n=116

|

|

Enterprise Bargain

|

30.0%/33.0%

|

32.7%/36.5%

|

30.0%/27.0%

|

7.3%/3.5%

|

n=110

|

|

Interested Transaction

|

95.8%/97.4%

|

4.2%/2.6%

|

—/—

|

—/—

|

n=117

|

Note: The percentage appearing in each cell before the solidus is the percentage of respondents who thought that the transaction would be handled in this way; the percentage after the solidus is the percentage of respondents who thought that the transaction should be handled in this way.

What is immediately noticeable is that the respondents appear to believe, on the whole, that the conflicts are handled in the manner they should be — the differential is minor. However, even though respondents appear to think that the conflicts are handled as they should be, in the first two cases there is no consensus as to how the transactions should be handled. Although this is not included in Table 4, this variation cannot be attributed to different practices in different companies, as there is substantial variation within the responses for individual GCs. There is not a single GC, for which responses were received from two or more directors, in which all respondents were unanimous on a method for handling the first two transactions. Only the third transaction — the paradigm conflict — elicited near-unanimous responses, which indicates that the perceptions of the handling of political conflicts is highly imprecise, confirming the central argument of this article.

Cross-tabulating the ‘would’ and ‘should’ results indicates that the results are more complicated than Table 4 suggests. First, the proximity of the ‘would’ and ‘should’ percentages for each of the options for the first two hypotheticals suggests that most respondents gave the same answer for both questions. That is not, in fact, the case. The divergence is greater for the enterprise bargain hypothetical, which is set out in Table 5.

TABLE 5: CROSS-TABULATION OF RESPONSES TO HOW THE

CONFLICT IN THE ENTERPRISE BARGAIN TRANSACTION WOULD

AND SHOULD BE HANDLED

|

|

SHOULD BE HANDLED:

|

|

|||

|

WOULD BE HANDLED:

|

Declare,

absent

|

Declare,

deliberate,

abstain

|

Declare,

deliberate

|

No

reference

to interest

|

Total

|

|

Declare, absent

|

27

|

3

|

3

|

—

|

33

|

|

Declare, deliberate, abstain

|

5

|

30

|

—

|

—

|

35

|

|

Declare, deliberate

|

1

|

7

|

25

|

—

|

33

|

|

No reference to interest

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

4

|

7

|

|

Total

|

34

|

41

|

29

|

4

|

108

|

Note: The cell records the count of the number of directors who ofered the particular combination of responses paired for each cell. There are 13 missing values.

The shaded cells are those where the transaction is handled as the respondent thinks it should be. The cells to the south-west of the shaded diagonal — containing 16 responses — are those where the respondent believes the transaction is handled less onerously than it should be. The cells to the north-east of the shaded diagonal — containing six responses — are those where the respondent thinks that the transaction is handled more onerously than it should be. The equivalent numbers for the country services hypothetical are nine and three. These results indicate that handling the transaction less onerously than it should be is a particular concern, and reflects perceptions of weak governance or doubtful ethics.

The ambiguity associated with the treatment of these transactions is also reflected when we cross-tabulate separately the ‘would’ responses for both the enterprise bargain and the country services hypothetical, and then the ‘should’ responses. The similar percentage of respondents for each category reported in Table 4 implies substantial convergence, but Table 6 contradicts this perception.

TABLE 6: CROSS-TABULATION OF RESPONSES TO HOW THE

CONFLICT IN THE ENTERPRISE BARGAIN TRANSACTION AND THE

COUNTRY SERVICES TRANSACTION WOULD BE HANDLED

|

|

ENTERPRISE BARGAIN

|

|

|||

|

COUN TRY SER VICES

|

Declare,

absent

|

Declare,

deliberate,

abstain

|

Declare,

deliberate

|

No

reference

to interest

|

Total

|

|

Declare, absent

|

15

|

9

|

5

|

1

|

30

|

|

Declare, deliberate, abstain

|

10

|

21

|

6

|

1

|

38

|

|

Declare, deliberate

|

5

|

4

|

17

|

—

|

26

|

|

No reference to interest

|

3

|

2

|

5

|

4

|

14

|

|

Total

|

33

|

36

|

33

|

6

|

108

|

Note: The cell records the count of the number of directors who offered the particular combination of responses paired for each cell. There are 13 missing values.

In Table 6, the shaded cells are those where respondents indicated the two transactions should be handled in the same way. The cells to the south-west of the shaded diagonal — containing 29 responses — are those where the respondent thinks that the conflict in the case of the enterprise bargain would be handled more onerously than the conflict in the case of country services. The cells to the north-east of the shaded diagonal — containing 22 responses — are those where the respondent thinks that the conflict in the case of the enterprise bargain would be handled less onerously than the conflict in the case of country services. There is clearly much disagreement. This carries over to when the comparison is made between how the two transactions should be handled: the results are similar to those in Table 6 and have not been reported.

To explore the factors influencing a respondent’s perception of the application of directors’ duties, and the effects of portfolio. These factors are related to the results, but not always in a predictable manner.

The impact of the respondents’ perception of their generic director’s duty (as reported in Table 3), surprisingly, has little or no effect on the handling of the conflict. For the country services transaction, it is surprising that those seeing themselves as implementing the minister’s wishes or serving constituency interests all chose to be absent or to abstain. By contrast, the lowest percentage of respondents choosing to be absent were those who regarded their duty as maximising value. The effect is not significant, however, and disappears entirely in the enterprise bargain transaction.

Portfolio has at least some weak effects on the perception of directors’ duties. Its effect seems to be stronger in relation to the enterprise bargain transaction. In the country services transaction, 87 per cent of respondents in Portfolio C would have absented themselves or abstained, compared to an average of 60 per cent for the other portfolios. The response is much the same for how those respondents thought that transaction should have been handled. Neither effect is significant, however. These results are stronger in relation to the enterprise

bargain transaction, as Table 7 demonstrates. The result is significant at p<0.05. The result for the same test on how the transaction should have been handled is even more significant at p<0.01.

TABLE 7: HOW THE CONFLICT IN THE ENTERPRISE BARGAIN TRANSACTION WOULD BE HANDLED (BY PORTFOLIO)

|

|

Portfolio A

|

Portfolio B

|

Portfolio C

|

Total

|

|

Declare, absent

|

13

|

14

|

6

|

33

|

|

Declare, deliberate, abstain

|

15

|

14

|

7

|

36

|

|

Declare, deliberate

|

21

|

11

|

1

|

33

|

|

No reference to interest

|

1

|

7

|

—

|

8

|

|

Total

|

50

|

46

|

14

|

110

|

X2 = 14.833, df = 6, p<0.05

In this article, I have examined the nature of accountability in GCs. Although in certain respects it may be desirable to use the corporate governance mechanisms of BCs in GCs, the basic conception of accountability does not translate perfectly to the GC. The differences are substantial, but they have scarcely been considered in either the scholarly literature or the governmental policy justifications for corporatisation. This article argues that it is the pervasion of non-efficiency motives and multiple agency relationships that deprives GCs of the precisely specified accountabilities of BCs, and their perfect fit with the governance obligations arising from the fiduciary concept. This is demonstrated empirically through the ambiguity and range of responses to the survey on the nature of the GC director’s duty.

At the risk of overgeneralising, this analysis incidentally casts doubt on Paul Finn’s ambitious attempt to mate the fiduciary duty to public law.[99] While constraints on certain forms of political behaviour are probably desirable, my analysis suggests that a standard imposing a requirement of selflessness in a public law context is unrealistic, because of its failure to recognise the inevitability of self-interest seeking by politicians and those wielding public power.

Finally, the article suggests the need to develop, where necessary, governance mechanisms which are better suited to the distributive functions of GCs and their interface with interest groups. While there is much tension between representational and ethical accountabilities where the board is used to satisfy both, greater progress might be made by using governance processes which address each accountability form separately. For example, a GC might be appointed with a board of non-executive directors who are independent of political parties and interest groups, but legislation may require that in formulating strategic plans the directors consult with an advisory board which is specifically responsible for canvassing the opinions of users, the community and other interest groups. Alternatively, stronger standards of disclosure should be required in order to bring a greater degree of transparency to the interests and negotiations between interest groups, the board and individual directors. The approach of directors to transactions which affect interest groups makes it clear that accountabilities are imprecise both in theory and practice.

To conclude, I make the following point: the scholarly success of public choice theory, such as it is, is not its specific predictions about the welfare effects of legislation, but its debunking of the romantic view of government. It has taught us to view governments as they are. However, the corporatisation phenomenon has perhaps been a little too swift to ignore the governmental attributes that continue to inhere in GCs. In particular, we need to understand how rent-seeking and the competition for pressure groups affect investment and other decisions of GCs. This will then help us to develop realistic accountability goals for GCs, and corporate governance mechanisms that fit these goals.

[*] Professor, Faculty of Law, Griffith University; Director, Business Ethics and Regulation Program, Key Centre for Ethics, Law, Justice and Governance. This paper forms part of a project funded by Queensland Treasury and the Australian Research Council. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author, and are not necessarily the views of Queensland Treasury or the Australian Research Council.

[1] See, eg, Adam Przeworski, Susan Stokes and Bernard Manin (eds), Democracy, Accountability, and Representation (1999); American Law Institute, Principles of Corporate Governance: Analysis and Recommendations (1992).

[2] Michael Froomkin, ‘Reinventing the Government Corporation’ [1995] University of Illinois Law Review 543, 558.

[3] There is a larger body of economic research on the effects of relations in which an agent has multiple principals: see, eg, Avinash Dixit, ‘Incentives and Organisations in the Public Sector: An Interpretive Review’ (Paper presented at the seminar on Incentives in Public Sector and other Complex Organisations, University of Bristol, 22–23 March 2001), <http://www.bris.ac.uk/cmpo/workshop/pippsdixit.pdf> at 5 August 2002. The situation we examine here is related, but differs in the imprecise identity of the actual principals.

[4] A wide range of nomenclature is used to describe these organisations in Australia, depending on the kind of organisational form (eg, not every state-owned enterprise is incorporated and those that are not should not be described as a corporation), and the jurisdiction. In order to avoid these somewhat partisan questions, I simply use the term ‘government corporation’.

[5] See, eg, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (‘OECD’), Governance in Transition: Public Management Reforms in OECD Countries (1995); National Commission of Audit (Australia), Report to the Commonwealth Government (1996); Industry Commission (now the Productivity Commission), Competitive Tendering and Contracting by Public Sector Agencies (1996).

[6] Independent Committee of Inquiry into Competition Policy in Australia, National Competition Policy (1993).

[7] Margaret Allars, ‘Private Law but Public Power: Removing Administrative Law from Government Business Enterprises’ (1995) 6 Public Law Review 44; Sally Pitkin and Diana Farrelly, ‘Government-Owned Corporations and Accountability: The Realm of the New Administrative Law’ in Berna Collier and Sally Pitkin (eds), Corporatisation and Privatisation in Australia (1999) 251.

[8] Paul Finn, ‘Public Trust and Public Accountability’ (1994) 3 Grifith Law Review 224; Christos Mantziaris, ‘Interpreting Ministerial Directions to Statutory Corporations: What Does a Theory of Responsible Government Deliver?’ (1998) 26 Federal Law Review 309; Charles Sampford, ‘Law, Institutions and the Public/Private Divide’ (1991) 20 Federal Law Review 185. Cf Michael Whincop and Mary Keyes, ‘Corporation, Contract, Community: An Analysis of Governance in the Privatisation of Public Enterprise and the Publicisation of Private Corporate Law’ [1997] FedLawRw 2; (1997) 25 Federal Law Review 51. See also Hughes Aircraft Systems International v Airservices Australia [1997] FCA 558; (1997) 76 FCR 151.

[9] Finn, above n 8.

[10] See, eg, Queensland Government, Corporatisation in Queensland: Policy Guidelines (1992) 22, 63.

[11] Rent-seeking describes any form of behaviour designed to redistribute in one’s favour the rents associated with particular assets or enterprises — the surplus economic returns beyond those necessary to retain the asset in its use. Rent-seeking can readily occur in private relations, for example, where one party makes an opportunistic threat not to perform a contract unless the gains from trade are redistributed. However, the term is also commonly used in the context of public choice theory, where it describes the behaviour of interest groups who seek legislation or other political acts that redistributes income and assets in their favour.

[12] See below Part II for a discussion of these private law means.

[13] For a useful summary, see John Langbein, ‘The Contractarian Basis of the Law of Trusts’ (1995) 105 Yale Law Journal 625, 632–3.

[14] For a definition, see Douglas G Baird, Robert H Gertner and Randall C Picker, Game Theory and the Law (1995) 309.

[15] See above n 8.

[16] Aberdeen Railway Co v Blaikie Bros (1854) 1 Macq 461; [1843–60] All ER Rep 249; Regal (Hastings) Ltd v Gulliver [1967] 2 AC 134.

[17] As the number of beneficiaries increases, the likelihood of diverging interests between the beneficiaries increases, which expands the scope for self-serving action by the fiduciary.

[18] The more homogeneous the interests of multiple beneficiaries, the easier it should be to administer a standard of selflessness, since the beneficiaries can be treated ‘as one’.

[19] The more complex the managerial tasks, the harder it is for a court to make an affirmative finding that the fiduciary’s action has violated the fiduciary duty without a substantial increase in the risk of false positives. See generally Kenneth B Davis, ‘Judicial Review of Fiduciary Decisionmaking: Some Theoretical Perspectives’ (1985) 80 Northwestern University Law Review 1; Alan Schwartz, ‘Relational Contracts in the Courts: An Analysis of Incomplete Agreements and Judicial Strategies’ (1992) 21 Journal of Legal Studies 271.

[20] The more distributive discretion a fiduciary has, the greater the risk that it will be exercised with partiality or influenced by side payments.

[21] Harry DeAngelo, ‘Competition and Unanimity’ (1981) 71 American Economic Review 18.