University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

‘INDEFINITE, INHUMANE, INEQUITABLE’ – THE PRINCIPLE OF EQUAL APPLICATION OF THE LAW AND THE NATURAL LIFE SENTENCE FOR MURDER: A REFORM AGENDA

I INTRODUCTION

Approximately 30 convicted murderers have been sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of release to parole since this punishment was instituted in New South Wales in January 1990. The natural life sentence was a part of the then Coalition Government’s ‘truth in sentencing’ reforms of the sentencing system.

In this article, it will be argued that not only is the indefinite nature of the sentence of life imprisonment inhumane, but the available evidence graphically demonstrates an eclectic approach by the judiciary to the practical application of the natural life sentence resulting in a clearly inequitable distribution of this ultimate form of punishment. This is contrary to one of the most basic tenets of the common law legal system, that the law should be applied equally to all persons. In an era of ‘law and order’ politics with the emphasis on a retributive and incapacitative policy approach to sentencing, the legislature has failed to provide meaningful guidance to the judiciary when drawing the line between cases of murder deserving natural life imprisonment as opposed to the option of a determinate, albeit lengthy, term of imprisonment. In turn, the appellate courts have struggled to formulate essential sentencing criteria for imposition of the life sentence. Some recurring factors have been identified, including the mode of killing, the number of victims and evidence of the future dangerousness of the offender. There is, however, no evidence of consistency in the approach to weighting these factors or promoting particular objectives and sentencing principles in the instinctive synthesis method adopted by sentencing judges.

Options for reform of the natural life sentence for murder in New South Wales require careful consideration. A proposal is made for judicially reviewable ‘life sentences’ which, at least in the longer term, would make the distribution of this indefinite form of punishment more equitable so that ‘like’ cases may be treated ‘alike’.

II INDEFINITE – A BRIEF EVOLUTION OF THE NATURAL LIFE SENTENCE

Penal servitude for life was substituted as the mandatory penalty for murder in New South Wales following the abolition of the death penalty for that crime in 1955. In that context, the meaning of the sentence of penal servitude for life1 retained the misleading and vague character it had largely had throughout the history of its existence. It rarely meant that a person would actually be kept in custody for the rest of his or her natural life. Rather, it was an indeterminate sentence2 subject to review at a time deemed appropriate by the executive; symbolically harsh but practically flexible.

Data from the various administrative boards that were created within the structures of the New South Wales executive government to consider the release of life sentence prisoners reveals that from the time of universal commutation and eventual abolition of the death penalty to the end of the 1970s, the large majority of prisoners serving life sentences for the crime of murder could expect to be released within 15 to 20 years of conviction.3 Further, available data indicates that in the decade immediately preceding the ‘truth in sentencing’ reforms it became unusual for a life sentence prisoner to serve more than 13 years in custody and exceptional to serve any more than 15 years.4

Following the election of a coalition government in New South Wales in March

1988, the symbolic nature of the sentence of life imprisonment

continued to be

reflected through media reports that the government’s penal policy for

murder was that it would ‘bring

automatic life imprisonment, in

practice not less than 20 years’.5 At the same time,

however, there was evidence of a concomitant movement away from such symbolism

to ‘truth in sentencing’:

the same media reports revealed that

‘[j]udges will be given the power to order, rather than suggest,

that a prisoner never be released in cases such as the Anita Cobby

murder’.6

The ‘truth in sentencing’ reform to

life imprisonment ultimately came in the shape of section 19A of the Crimes

Act 1900 (NSW) (‘Crimes Act’), which provided:

(6) Nothing in this section affects the prerogative of mercy.

The new Government, therefore, reinforced its retributive approach to correctional policy by introducing a natural life sentence as the maximum penalty for the crime of murder.7 In this regard, academic commentator George Zdenkowski emphasised the finality of such a sentence in that it ruled out ‘any prospect of rehabilitation’.8 Allied to this was the potential unfairness generated by the impossibility of predicting with any accuracy ‘the divers circumstances which may arise in 20 years, let alone 50 [years] ’.9 Further, aside from the economic cost of maintaining a prisoner in custody for an indefinite period of time, Zdenkowski drew out the human misery associated with such a sentence in that it ‘deprives the offender of any humanity ... [and] is a recipe for despair and destructive behaviour’.10 Essentially, he viewed the legislative provision of a natural life sentence as ‘[s]tate-authorised vengeance ... [raising the spectre of] the resurrection of capital punishment’.11

It is arguable that part of the impetus for change in sentencing for murder lay in the government’s desire to be rid of the controversial and politically sensitive decision making process for the release of life sentence prisoners on licence. By giving the judiciary responsibility for the actual formulation of sentences in murder cases, including not only the power to impose the maximum natural life sentence but also new powers to determine when existing life sentence prisoners would become eligible for release to parole,12 meant that in the future the judges, rather than the government and its Ministers, would be the ones subject to intense media and public scrutiny when convicted murderers were eventually released from prison.13

Another salient factor in the overall effect of the legislation was the Government’s implicit aim to more closely ‘manage’ sentencers and their discretion. Although this is not improper in a parliamentary democracy where the legislature has a legitimate role in sentencing law and policy, there was no express legislative statement as to the principles and factors relevant to the actual determination of the appropriate punishment in an individual case of murder. The relevant legislation, section 19A of the Crimes Act, simply contained a description of the extent of the power of the courts in sentencing for murder and the meaning of the ultimate sentence. The identification of the factors relevant to the imposition of the natural life sentence and the relative weight to be accorded to these factors was left to the judiciary.

The next step in the evolution of the natural life sentence in New South Wales was the provision for a ‘mandatory life sentence’ that resulted from Australian Labor Party policies formulated for the 1995 election campaign. Section 61(1) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) (‘Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act’) sets out the circumstances in which it is mandatory to impose a natural life sentence in relation to a murder conviction.14 The level of culpability of the convicted murderer must be ‘so extreme that the community interest in retribution, punishment, community protection and deterrence, can only be met through imposition of that sentence’. Arguably, this provision represents little more than a political manoeuvre by the Government that would have a minimal impact on the sentencing practice of the judges responsible for dealing with any crimes of that nature. The general terms of the legislative provision taken from the common law of sentencing did nothing to provide the legislative guidance required to establish relevant criteria for determining who should receive a natural life sentence as opposed to the certainty of a determinate sentence.

In the immediate historical context of the creation of the indefinite life sentence for murder, it is certainly arguable that this significant change was a product of ‘law and order’ politics involving ‘an intensification of punishment levels and an exploitation of fear’15 rather than reflecting substantive penological aims. Accordingly, it might be contended that from a government viewpoint, specific legislative guidance as to the conditions that should exist before imposition of this ultimate sentence was not desirable. Rather, it was substituted by a wave of political rhetoric emphasising ‘truth in sentencing’ and getting ‘tough’ on crime and criminals. In the seemingly apt words of Andrew von Hirsch, a leading contemporary sentencing theorist, the natural life sentence may be characterised as ‘largely concerned with fostering and exploiting public resentment of crime and criminals’,16 particularly serious crimes characterised as ‘evil’, ‘heinous’ or ‘horrific’. The particular social context of this sentencing ‘reform’ included some ‘horrific’ murder cases, such as the killings of Anita Cobby and Janine Balding.17 Sustained and graphic media coverage of these murder cases served to generate public outcry and animosity against such crimes and against those who were responsible for their commission. The perception of strong community discontent with the criminal justice system, and with the sentencing of criminals in particular, allowed for the development of certain extreme political solutions in the name of restoring ‘truth in sentencing’ and providing transparency in decision making. It is clearly open to contend that the natural life sentence is an example of such an extreme political solution.

III INHUMANE – THE PRACTICAL EFFECTS OF THE INDEFINITE FORM OF LIFE IMPRISONMENT

Every man, whoever he may be, and however low he may have fallen, requires, if only instinctively and unconsciously, respect to be given to his dignity as a human being. The prisoner is aware that he is a prisoner, an outcast and he knows his position in respect to the authorities, but no brands, no fetters, can make him forget that he is a man. And since he is a human being, it follows that he must be treated as a human being. God knows, treatment as a human being may transform into a man again even one in whom the image of God has long been eclipsed.18

Allied to the indefinite nature of the natural life sentence with no prospect for early release is its inherent inhumanity, forcefully demonstrated above in the contemporaneous commentary of Zdenkowski.19 The ‘terrible significance’ of the sentence of life imprisonment has also been judicially recognised; exemplified by the oft quoted statement of Hunt J in R v Petrof:20

The indeterminate nature of a life sentence has long been the subject of criticism by penologists and others concerned with the prison system and the punishment of offenders generally. Such a sentence deprives a prisoner of any fixed goal to aim for, it robs him of any incentive and it is personally destructive of his morale. The life sentence imposes intolerable burdens upon most prisoners because of their incarceration for an indeterminate period, and the result of that imposition has been an increased difficulty in their management by the prison authorities.21

It is incontestable that ‘life’, that is, one’s individual manner of living through the activities one takes part in at given places and at given times, is profoundly changed by the deprivation of liberty involved in the punishment of imprisonment. This is because the condition of imprisonment imposes confinement in a particular place with regimentation and severe restrictions on freedom of movements and activities. Accordingly, one argument against this punishment is the possible violation of individual human rights involved in imprisonment for the term of a person’s natural life. As Australia is a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,22 the existence of the natural life sentence in New South Wales arguably represents a potential breach, or is at least inconsistent with the spirit, of Article 7, which prohibits ‘cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment’. It certainly may be contended that to condemn a human being to the deprivation of liberty associated with imprisonment, which, for convicted murderers, is likely to take the form of maximum security for an indeterminate number of years, and to completely remove any hope of freedom in the future, is an inhuman treatment or punishment. Although an argument along these lines has not yet been successful in any decided cases in Australia, the United States or any other common law country,23 there appears to be scope to formulate plausible submissions based on the growing empirical evidence of the deleterious effects of indefinite long-term incarceration.

This type of argument has been mooted by foremost Canadian sentencing academic, Allan Manson, in relation to the guarantee against cruel and unusual punishment contained in section 12 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1982.24 Although the Supreme Court of Canada has previously ruled that the mandatory life sentence for first degree murder in that jurisdiction does not violate the section 12 guarantee because of the potential for release to parole after serving 25 years, the constitutional validity of a ‘whole of life’ sentence has not directly arisen for determination. Specifically, there has been no consideration of ‘the human impact of long-term confinement’ in relation to the section 12 guarantee.25 Accordingly, as Manson has observed, the constitutional position of a natural life sentence in Canada has not been expressly determined and an interesting point arises as to whether the Supreme Court may be persuaded to reconsider its position on a qualitative basis ‘from the perspective of the effects of long-term confinement on mental and physical health, and potential reintegration’.26

The issue of human rights and imprisonment for the whole of one’s natural life has also been the subject of judicial scrutiny in England, a jurisdiction which until recently was largely characterised by executive mechanisms for ‘tariff’ setting in cases of mandatory life sentence prisoners, including all convicted murderers. The Human Rights Act 1998 (UK) c 42 has created a fertile environment for change in this jurisdiction with some important recent judgments of the European Court of Human Rights and the House of Lords examining the intersection between certain guarantees of human rights and the process of determination of tariffs for mandatory life sentence prisoners.27 The fixing of a tariff was characterised by the House of Lords in R (on the application of Anderson) v Secretary of State for the Home Department28 as a sentencing exercise that must be solely undertaken by an independent and impartial tribunal such as a court. Even though it seems that ‘in future, it will be judges, not politicians, who will set the appropriate term for murderers’29 in England and Wales, the potential for a ‘whole of life’ tariff still exists. As Lord Steyn observed in Anderson, ‘there may still be cases where the requirements of retribution and deterrence will require life long detention’.30 There may, however, be a future challenge in the European Court of Human Rights to the fixing of a ‘whole of life’ tariff as a violation of human rights, such as the prohibition against ‘inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment’ contained in Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights.31 A challenge of this nature may find support through the fact that a significant number of European jurisdictions do not have the option of a life sentence without the possibility of parole in the sentencing armoury of their courts.32 These standards provide an important human rights benchmark in relation to the limits of humane treatment or punishment in modern western industrialised nations.

Overall, the inhumanity of the punishment of life imprisonment with no possibility of parole provides a strong foundation for the argument that the natural life sentence should be excluded as a sentencing option at first instance. There is no place in contemporary penal systems for the base human notions of revenge that fuel the inhumanity necessarily connected with the natural life sentence. Allied to this concern is the political opportunism of ‘playing to the grandstand’ of community outrage, which is incongruous with the dispensing of justice in an impartial and objective judicial forum. Truth in sentencing, although providing a more transparent sentencing system where sentences imposed actually match sentences served by offenders, has made for a much harsher sentencing system with a real and significant increase in the average periods served in custody across a broad range of offences, including murder.33

IV THE PRINCIPLE OF EQUAL APPLICATION OF THE LAW

The courts have recognised that one of the most basic

tenets of the common law legal system is that the law should be applied equally

to all. This principle is also found in significant human rights

instruments34 and constitutional bills of rights of countries

including the United States of America and Canada.35 Under this idea

‘every person is entitled to equal respect from the law and its

processes’, and ‘non-discrimination’

is integral to the

functioning of the legal system.36

In the particular context of

sentencing, the principle of equal application of the law has been recognised by

the Australian High

Court in the case of Lowe v The

Queen,37 specifically to achieve parity and consistency in

the sentencing of co‑offenders:

Just as consistency in punishment – a reflection of the notion of equal justice – is a fundamental element in any rational and fair system of criminal justice, so inconsistency in punishment, because it is regarded as a badge of unfairness and unequal treatment under the law, is calculated to lead to an erosion of public confidence in the integrity of the administration of justice. It is for this reason that the avoidance and elimination of unjustifiable discrepancy in sentencing is a matter of abiding importance to the administration of justice and to the community.38

Following this important judicial statement as to the doctrine of equal justice, Gaudron J later emphasised in R v Siganto39 that principles relating to equal application of the law and parity in sentencing are not restricted to cases involving co-offenders. Her Honour emphasised that the ‘principle of equal justice is of ... fundamental importance’40 and that where legislation alters sentencing parameters, judges must be careful to ensure that ‘the sentence to be imposed will produce no greater disparity than is necessary to give effect to the legislated change’.41 Arguably, this judicial comment has direct application to the change in New South Wales from a maximum indeterminate ‘life’ sentence for murder to a natural life sentence. Through this legislative measure, the end point for the judicial application of the principle of proportionality, namely, that a sentence must be imposed ‘commensurate with the seriousness of the crime’,42 was extended. The principle of equality before the law, however, remains an overriding consideration in formulating an appropriate sentence and in ensuring there is no unjustifiable disparity in sentences imposed upon offenders convicted of murder.

The principle of equal application of the law has been recognised and has purported to be applied by the New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal. Notably, in the guideline sentencing case of R v Jurisic,43 Spigelman CJ stated:

That there are a multiplicity of factors that need to be considered in sentencing has long been recognised. There is, however, a tension between maintaining maximum flexibility in the exercise of the discretion, on the one hand, and ensuring consistency in sentencing decisions, on the other. Inconsistency in sentencing ofends the principle of equality before the law. It is itself a manifestation of injustice. It can lead to a sense of grievance amongst individuals on whom uncharacteristically severe sentences are imposed and amongst the broader community, or victims and their families, in the case of uncharacteristically light sentences.44

More recently, in an extra-curial statement, Spigelman CJ, whilst recognising that differences in the approach of individual judges to sentencing were unavoidable, reiterated the paramount importance of equal application of the law and consistency in sentencing:

Inevitably there will be differences on the part of judges in terms of their philosophical approaches to the exercise of the sentencing task. Nevertheless, it would fundamentally undermine public confidence in the administration of criminal justice if it became widely believed that the result was a complete lottery based on who the judge was. It is essential for the maintenance of public confidence in the administration of justice that the outcomes of similar cases are, within reasonable bounds, the same. Consistency in sentencing must be more than empty rhetoric. That is a primary task of the Court of Criminal Appeal.45

In the case of R v Stringer,46 Adams J deliberated extensively about the principle of equality before the law and the associated doctrine of equal justice, ultimately observing that it is ‘a fundamental element of the rule of law, if not as a substantive right, then as necessarily informing the content and application of the common law, including the rules applying to the interpretation of statutes’.47 He emphasised that the principle of equality is important ‘as a fundamental element of community standards, though it may have a wider significance’.48 This statement reflects the words of eminent desert theorist, Andrew Ashworth, who also stressed that equality before the law is ‘a fundamental value which cannot simply be cast aside: it stands for propositions about respect for human dignity, and impartiality in the administration of criminal justice’.49 According to Ashworth, proportionality, in the way that it finds expression in the modern theory of ‘just deserts’, ‘giv[es] effect to the principle of equality before the law’.50 Although Ashworth acknowledges that there is significant social inequality evident in society and that places ‘notions of proportionality and desert in the allocation of punishment ... under strain’,51 it does not prevent important efforts ‘to make sentencing policy more coherent and fair’.52

This fundamental common law principle has a prominent role to play in any analysis of the approach of the New South Wales judiciary to their task of sentencing in murder cases. Equal application of the law is a basic requirement for consistent sentencing practice that has been aligned to theoretical notions of proportionality in sentencing. With this in mind, there is empirical evidence from sentencing in the most serious cases of murder to suggest that the practical application of the natural life sentence has revealed an unacceptable clash with the fundamental principle of equality before the law. This evidence has also demonstrated that sentencing judges have acted contrary to this basic tenet of the legal system.

V INEQUITABLE – THE PRACTICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE NATURAL LIFE SENTENCE IN NEW SOUTH WALES

I researched and analysed murder cases resulting in the convicted murderer receiving a natural life sentence or a lengthy determinate sentence of imprisonment for the period between January 1990 and January 1997.53 My research reveals that this extreme punishment has not been applied equitably; it seems to be incapable of consistent application in the absence of clear criteria concerning the circumstances in which it should be applied. This assertion is supported by examples of murder cases which, based on factors identified as contributing to overall objective seriousness, could have fitted into either punishment category of natural life imprisonment or the category of lengthy determinate sentence.

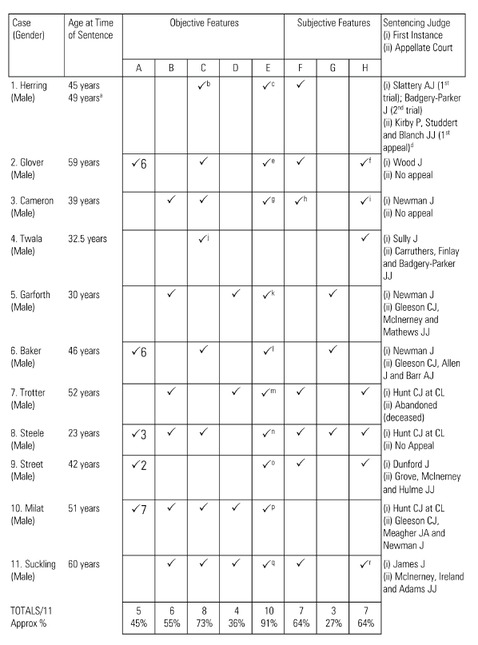

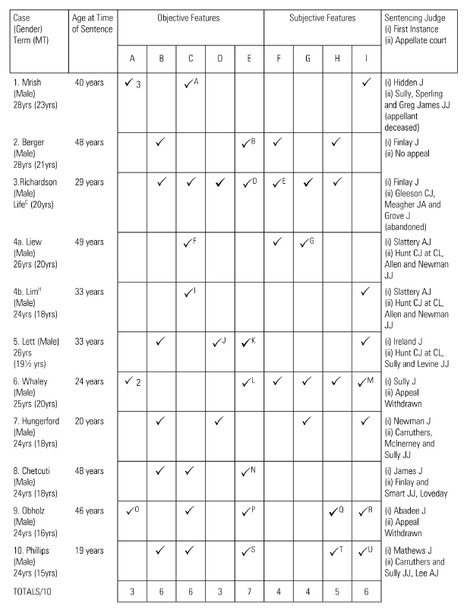

Since the introduction of the natural life sentence, judicial sentencing method for murder, characterised by very broad discretion, starkly reveals that there is no identifiable ‘litmus test’54 for deciding whether someone falls within the ‘worst’ category of murder offender deserving a natural life sentence. Recurring relevant factors from the cases where a natural life sentence was imposed for murder, between January 1990 and January 1997, are identified and tabulated in Table One. An equivalent exercise for cases where a lengthy determinate sentence was imposed for murder, during the same period, is reflected in Table Two. Tables One and Two are set out below at pages 167 to 172. The relevant considerations used in Tables One and Two are descriptive rather than discriminating factors. Appellate courts have not been of any great assistance in providing the necessary level of discrimination between cases at this most serious level so that sentencing ‘outcomes of similar cases are, within reasonable bounds, the same’.55

The statement of principle by Spigelman CJ in R v Jurisic, discussed above, arguably supports the general contention that where there is inconsistency in sentencing approaches and outcomes, there is injustice as a corollary for individual offenders. Although Spigelman CJ does not make specific reference to the natural life sentence for murder, the general statement may logically be applied to offenders within this specific offence category.

A particular manifestation of the disparity found in the natural life sentence murder cases is the significance of the age of the offender at the time of sentence. The findings in the tables demonstrate that the life expectancy of a person is not consistently considered in determining whether they should receive a natural life sentence or a lengthy determinate sentence. For example, some individuals upon whom natural life sentences were imposed, such as Steele and Garforth could have expected a further 40 to 50 years of life when sentenced for their crimes; however, others receiving the same sentence had statistical life expectancies ranging from 19.87 years, in the case Glover, to 37.6 years, in the case of Cameron.56

Starker evidence of disparity is revealed when comparison is made with the murder cases in which the longest determinate sentences were imposed on offenders in Table Two. Specifically, determinate head sentences ranging from 24 years up to a ceiling of 28 years imprisonment and minimum terms of between 15 and 23 years have been imposed as representing the next step down from a natural life sentence; this exemplifies vastly differential treatment. Taking 50 years as the upper level of life expectancy for natural life sentence prisoners, then, in real terms, the differences between the longest determinate sentences and natural life sentences are up to 22 years and potentially well in excess of that period. On what basis can actual sentences up to approximately 80 per cent longer for some crimes of murder be justified when all the cases analysed across both sentencing categories were characterised as falling at the most serious end of the spectrum of murder offences? The relevant sentencing factors identified cannot be described as being so decidedly different as to allow for such vast incongruity in sentencing outcome.

Within the various case examples, there is patent evidence of the relative youth of some prisoners being so overshadowed by the objective seriousness of the offence that it was accorded little or no weight in sentencing, notably in the case of R v Steele.57 In direct contrast, there are other very serious cases of murder, specifically R v Hungerford58 and R v Phillips,59 where youth was highlighted as a principal mitigating factor to the extent that a natural life sentence was avoided either solely or primarily on that ground.60 When an overall comparison of the seriousness of the objective circumstances and other relevant subjective factors is made between these cases, there are certain differences; however, these differences are not so glaring as to justify such large discrepancies in sentencing outcome. The youthful prisoners serving natural life sentences could potentially serve more than double the amount of time in prison than those young offenders sentenced to determinate sentences of 24 or 25 years. Accordingly, it is difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile the widely disparate sentencing impacts resulting from differences in the ages and weight placed on the youth of those convicted of the most serious murders.

The case analyses also demonstrate that another notable factor in the perpetuation of disparity in sentencing for murder is the judicial categorisation of particular offenders as dangerous. Sentencing judges use the objective circumstances of a murder as an important indicator of dangerousness. This means that the characterisation of the factual circumstances of the offence carries significant weight. In addition, risk of future dangerousness is assessed using expert psychological and psychiatric evidence. When available to a court, psychiatric opinions about future dangerousness have provided an important, and, sometimes, primary basis for determination of the ultimate sentence in a number of the most serious murder cases. The use of this evidence presents serious concerns because of the largely subjective nature of these opinions.61 A cautious and qualified approach to this material has not been evident to date with inequitable outcomes discernible where there appears to have been a heavy judicial reliance on a particular psychiatric prognosis in contrast to the emphasis placed on other significant features of the case.

This contention can be specifically supported through a comparison of two

cases where the objective features of the single killing

were comparable and

where both offenders had previous convictions for murder or manslaughter. In

R v Cameron,62 the sentencing judge, in imposing a

natural life sentence, placed great weight on the statements made by the

psychiatrists about the

prisoner and their predictions about future

dangerousness. Justice Newman noted that the antisocial personality disorder

suffered

by Cameron was one that could not be treated. Also, it could not be

said with any certainty when he would be regarded as safe for

release into the

community, save perhaps for when he was so old or infirm that he was physically

not able to realise his homicidal

predisposition.63 A contrasting

sentencing outcome was reached in the case of R v

Richardson.64 The prisoner’s record for violent,

antisocial behaviour was clearly laid out before the sentencing judge who formed

the view

that Richardson had ‘no realistic prospects for rehabilitation

... and would regard him as a danger at large to the

community’.65 Nevertheless, a determinate minimum term of

imprisonment was fixed because a prediction as to whether there was some chance

of rehabilitation

and personal redemption could not confidently be made more

than two decades ahead.66 This reasoning against selective

incapacitation based on the predictions of psychiatrists is again evident in the

remarks of Finlay

J in the later case of R v Berger.67

This case involved objective circumstances and subjective features

comparable to those in the case of R v Cameron but resulted in a lengthy

and wholly determinate sentence rather than natural life imprisonment.

An

interesting illustration of the inconsistent approach of the courts towards

dangerousness is also provided in the case of R v Twala,68

where Badgery-Parker J, in the Court of Criminal Appeal, substituted a

natural life sentence that had been imposed at first instance

with a determinate

sentence. The basis for the substitution was that the prisoner’s

psychiatric profile had an important role

to play in the mitigation of the

objective gravity of the murder removing it from the ‘worst class of

case’ category.

Justice Badgery-Parker’s approach was in direct

contrast to the original sentencing judge’s finding that the

prisoner’s

psychological profile was of the utmost importance in

‘warranting a rational conclusion that there is a significant risk to

life

or bodily safety of any member or members of the community should the particular

offender be released’.69

Apart from the age and psychiatric profile of the convicted murderer, other relevant considerations identified in the murder case analyses, presented in the tables, also demonstrate that there has not been a consistent judicial approach to apportioning weight to these factors in order to reach reasonably equitable sentencing outcomes. These other relevant considerations include several objective factors, such as the killing of multiple victims, planning and premeditation, use of extreme cruelty or torture in carrying out the killings, sexual assault or other serious crimes committed as an incident to the killings, plus various subjective matters, for instance the extent of an individual’s prior criminal history, nature of their plea, and rehabilitation prospects.

The case in which the longest determinate sentence in Table Two was imposed,

R v Mrish,70 provides an important representation of

the inequitable weighting of the various objective and subjective factors to

determine punishment

in the most serious cases of murder. In R v Mrish,

Hidden J actually undertook an express comparison between the instant case

and those cases in which a natural life sentence had been

imposed up to that

time. The significant sentencing factors in R v Mrish included a plea of

not guilty, multiple victims, evidence of premeditation in two of the killings,

and a motive relating to personal

financial gain. Justice Hidden sought to

distinguish cases like R v Baker,71 R v

Glover,72 and R v Milat73 on the

basis that they involved the killing of six or more people, and that the

offenders in R v Glover and R v Milat were serial

killers74. He noted that in most of the natural life sentence cases

the killings were particularly brutal or callous75. It is not clear

how R v Mrish could be distinguished on that basis as one of his victims

was stabbed repeatedly and the other two were shot at close range following

careful planning. Other points of distinction noted by Hidden J were that in the

cases of R v Garforth,76 R v Trotter77

and R v Milat the victims were sexually assaulted. In all cases, with

the exception only of R v Baker, each of the offenders was considered to

be a continuing danger to society if released from custody, and ‘none of

them made out

a good subjective case, the evidence about their background being

either unfavourable or minimal’.78

The generalisations

stated by Hidden J do not strictly accord with the material presented in Table

One as it certainly might be argued

that the offenders in the cases of R v

Garforth and R v Baker made out reasonable subjective cases. In a

dissenting opinion in R v Baker, Allen J stated that Baker’s

natural life sentence should be quashed and substituted by a determinate

sentence of 28 years based

on the finding of a psychiatric disturbance at the

time of the killing. In doing so, Allen J undoubtedly gave some recognition to

this important subjective feature. Moreover, Milat’s subjective case was

not really unfavourable as it was the nature of the

murders for which he was

convicted that provided the evidence of future dangerousness.

Although Hidden J was careful to say the decided cases did not circumscribe his determination, it is arguable that he sought to contrast the cases on the basis of specific criteria. It is interesting to note that although Hidden J did not find that the premeditated and multiple murders in R v Mrish fell into the ‘worst class of case’, he imposed the longest ever determinate sentence under section 19A of the Crimes Act up to that point in time, and exactly the same sentence which Allen J considered appropriate in his dissenting judgment in the appeal of R v Baker. Ultimately, even though Hidden J sought to distinguish R v Mrish from R v Baker it is somewhat difficult to entirely appreciate his reasoning in this regard. Certainly, Baker had three more victims; however, Baker pleaded guilty, was of a similar age to Mrish, had a comparable criminal record, and, on available evidence, could not be regarded as a continuing danger to the community. The reference to six or more victims as opposed to three, four or five appears to be a somewhat arbitrary attempt by Hidden J to provide a cut-off point for which cases of multiple murder may fall on the ‘natural life sentence’ side of the dividing line. It is not exactly clear from his reasoning as to why the higher ‘head count’ may possibly be seen as demonstrating a more readily identifiable propensity for violence and killing on the part of the multiple offender which carried with it a wholly indeterminate sentence of imprisonment as opposed to giving the offender some prospect of early release.

The instinctive synthesis approach, which has been the methodology applied to sentencing by Australian courts,79 hides the precise formulations of weight apportioned to various relevant factors identified in a case as it

purports to derive the appropriate sentence by looking at all the relevant factors and sentencing principles, and determining their relative weights by reference to all the circumstances of the case ... in a single step or synthesis, not sequentially.80

It allows sentencing judges to persist in using vague terms like ‘substantial’ or ‘weighty’ to give general indications of the relative importance of particular factors. This approach has, therefore, not provided the basis for a useful form of guidance to judges sentencing convicted murderers at first instance. Rather, discordant approaches and inequitable sentencing outcomes have ensued meaning that the fundamental principle that ‘like cases should be treated alike, and different cases differently’ is not being followed.

Despite the removal of the largely concealed executive mechanisms from the process of sentencing for the whole of a person’s life in murder cases,81 the judiciary in New South Wales have not implemented a distinctly principled and consistent approach to the imposition of this maximum penalty. Rather, there has been notable differential treatment of cases in the important division between levels of seriousness deserving of the maximum natural life sentence and ‘lesser’ determinate sentences, resulting in inequitable sentencing outcomes. Further disparity has been evident through the life sentence redetermination process, which permits the fixing of a non-parole period to a head sentence of life imprisonment for cases where the life sentence was imposed prior to 1990.82 The New South Wales Law Reform Commission gave particular emphasis to this point when it recommended that judges sentencing for murder under section 1 9A of the Crimes Act should have the discretion to affix a minimum term to a natural life sentence.83 Clearly, there is a pressing need for reform.

VI A REFORM AGENDA – ‘LIFE’ IN THE FUTURE

The judicial power to completely close off the prospect of early release from imprisonment exists when a natural life sentence is imposed for murder. The convicted murderer can apply for leave to appeal against the sentence to the Court of Criminal Appeal and, if this is not successful, a limited avenue of appeal by way of application for special leave to the High Court is then available.84 If all these avenues are exhausted, then save for exercise of the royal prerogative of mercy by the Governor, upon advice from the executive, the convicted murderer will never be released. All judicial decisions can be made within the compass of a relatively short period, perhaps a few years from the time of the offence,85 thus leaving such prisoners with the prospect of sometimes in excess of 40 years in continuous imprisonment with no review mechanism, judicial or otherwise, even though complete rehabilitation may be accomplished.86

In addressing the concerns about the inhumanity and inequity of the indefinite life sentence in New South Wales, it must be noted that the experience of other comparable jurisdictions, both within and outside Australia, has not provided a model for equitable and discriminating criteria in labelling the most serious cases of murder. Ideally, the natural life sentence should be repealed and replaced by a determinate maximum sentence of 30 or 35 years imprisonment. Such a figure is chosen to demonstrate the unique gravity of the offence and to attain ordinal and cardinal proportionality with the longest current maximum determinate sentence for other serious crimes of 25 years imprisonment.

The current political reality in a continuing climate of ‘law and order’ politics in New South Wales is such that the primary argument for abolition of the natural life sentencing option in its present form is unlikely to be accepted. There is certainly room, however, for improvement of the existing system. If the natural life sentence is to be retained as the maximum sentence for murder then there should be a rigorous process for final imposition of this penalty making it much more difficult for a sentencing judge to reach this pinnacle.

A A Process of Judicial Review

The availability of a review process for natural life sentences is a mechanism that could achieve this aim in the long-term. Examples of current review processes are those for ‘indefinite sentences’ in other Australian jurisdictions87 and Schedule 1 to the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act, which provides a detailed procedure for the redetermination of ‘existing life sentences’ in New South Wales. This latter review process has been the subject of extensive judicial consideration throughout the 1990s,88 thus providing a larger volume of jurisprudence for analysis than the procedures for imposition of indefinite sentences have in Victoria, Queensland, and the Northern Territory.

These various review procedures for indeterminate sentences involve nominated periods of incremental judicial review of an offender convicted of murder, or other serious crimes. Particular documents and reports must be prepared for the review hearing and designated matters must be taken into consideration to enable the court to make an informed decision as to the offender’s future and the protection of the community.

The advantages of such a review procedure are the transparency of the whole process. For example, there are express legislative provisions or judicial power to order times when the review is to take place, specific matters and/or documents to be taken into consideration, and provision for open public hearings with the opportunity for all relevant and interested parties to participate or simply be present.89 The requirement that reasons be articulated for any decision made and the availability of ordinary avenues of appeal when such procedures are utilized is important for the accountability of judicial officers. The establishment of discernible benchmarks in such cases is a critical part of the ultimate promotion of consistent and equitable treatment for these serious offenders. Also, there is a plausible basis for the contention that a model likely to promote consistent individualised justice will more readily achieve proportionality in the ‘just deserts’ sense, the primary purpose of sentencing.

1 Judicial Review and the Family of the Ofender and the Victim

One potential drawback of such procedures is the impact on those directly affected by the process, including the offender and his or her family plus the family of any victims. This could arise through the perhaps quite lengthy delay that will occur before knowing the final sentencing outcome. Arguably, such a process would only be used where a natural life sentence is seriously contemplated as the initial sentencing response. Accordingly, the process provides a benefit to the offender and his or her family in that the prospect of eventual early release is not immediately removed.

As to the family of any victims, there is an uncertainty involved in the utilisation of such a process which may make these people anxious and impatient. Arguably, however, there are benefits for the family of any victims who may choose to participate in the review process by attending future hearings and submitting material for consideration by the court, observing the incremental progress of the offender in the correctional environment via reports from the Serious Offenders Review Council and through expert prognoses as to any ongoing risk posed by the offender if released into the community. These people could be assured that such exceptional cases would be treated with respect for, and sensitivity to, the rights and interests of all parties involved. Apart from the rights of the family of any murder victim as declared in the Victims Rights Act 1996 (NSW),90 it is important to emphasise that cases would proceed with clear aims in mind. They would ensure that in punishing the offender proportionately to the offence and his or her individual culpability, he or she still retains fundamental human rights and would not be given a justifiable sense of grievance by any aspect of the process.

2 Judicial Review and Protection of the Public

Decisions of judges in the European Court of Human

Rights91 have repeatedly emphasised that ‘the lawfulness of

continued detention should be decided by an independent tribunal or court

at

reasonable intervals’92 particularly so that a

‘prisoner’s mental instability and dangerousness could be monitored

and a decision for release

taken, depending on the risk of danger to the

public’.93 Division of the sentencing task in very serious

cases of murder into a punitive element, for retribution and deterrence, and

then

periodic judicial monitoring of dangerousness of the individual offender to

determine the necessity for continued detention may be

an apt way of achieving

this protection.

The mechanism of a judicially ‘reviewable

sentence’ is strongly promoted by Peter Svensson as a fundamental step in

protecting

the public from dangerous offenders.

The main feature of the proposed scheme is the availability of reviewable sentences coupled to due process in order to monitor, not only the imposition of the reviewable sentence at first instance, but also to monitor continuity of that sentence and determine the release of an offender from a reviewable sentence. The central concept is to balance the perceived need for public protection with review by due process, especially in the release determination which is believed to be better vested in the courts – who are most experienced in administering concepts of natural justice and individual liberties – than in the executive by way of Governor’s or Sovereign’s Pleasure.94

Issues pertaining to fundamental human rights and the attainment of natural justice through any sentencing and associated review procedures are clearly more properly placed within the responsibility of an independent judiciary inside the context of a democratic society based on the continuing operation of the rule of law.

3 Judicial Review and the Convicted Murderer

There are compelling grounds for contending that the emotional frenzy at the sentencing hearing, immediately or soon after completion of a murder trial, is not the occasion when a decision should be made affecting the rest of a convicted murderer’s life. Why hand the final sentence down at this stage? Decisions to impose natural life sentences at this time, arguably, represent absolute forms of revenge and incapacitation. Such momentous decisions require time for reflection and rational thought, sometimes extensive periods, which cannot be initially determined with confidence and accuracy in every case.

Judges should not be expected to sentence convicted murderers on the basis of expert opinions or prognoses as to the future dangerousness of these individuals when predictions of dangerousness by psychiatrists have not been shown to be particularly reliable. Although protection of the public will become a primary aim in the case of an offender who represents a continuing danger if released into the community, there must be a sound evidential basis on which this conclusion is reached. The paramount aim of proportionality in sentencing will only be displaced where dangerousness is established by unequivocal and compelling evidence. As Finlay J remarked in imposing a life sentence with a minimum term in the case of R v Richardson, it is impossible to ‘foresee with confidence certainly more than two decades ahead as to whether there may then be some chance of rehabilitation and personal redemption’.95 Also, in the later appeal case of R v Crump,96 Mahoney JA emphasised the ‘inherent fallibility of (psychiatric and psychological) evidence’:97

The predictions of an astronomer as to the conjunction of the sun and the moon may ordinarily be accepted as reliable: it may be an obvious error to refuse to accept it. But the assessment of the emotional state of a person and, a fortiori, the prediction of what the person, in the future, will be apt to do, is inherently subject to greater uncertainty ... courts should not ask psychiatrists and psychologists to do more than, by the nature of their discipline, they can do. And in determining whether to act upon assessments made by experts in this area, a judge may, in my opinion, properly take into account the seriousness of the consequences of their being wrong.98

4 A Judicial View of Reviewable Sentences in Murder Cases

A major question when contemplating implementation of a reform such as the reviewable sentence in serious murder cases is what is acceptable and going to be utilised by the judiciary as a viable sentencing option? There are indications by the Court of Criminal Appeal and a number of Supreme Court judges for the need for a power to affix a non-parole period to the life sentence for murder in New South Wales, particularly in the comparatively recent cases of R v Harris,99 R v Ngo100 and R v Merritt.101 Also, a number of judicial observations have been made as to the utility of the life sentence redetermination procedures in reviewing the progress of convicted murderers and the clear potential for the reform of serious offenders in the custodial setting.102 These observations are exemplified by the comment of Wood J in R v McCaferty103 that when determining an application under section 13A of the Sentencing Act, the Court

is in fact in a position of considerable advantage since it has the opportunity of knowing how the prisoner has behaved since he was first sentenced and of the steps taken towards rehabilitation. That is even more important in a case such as the present, where the potential dangerousness of the offender and his unstable psychiatric condition would have been of paramount concern to the court, in accordance with the principles enunciated in Veen [No.2] ... it [is] important to pay full regard to the obvious legislative preference for determinate sentences and to the positive incentive which a minimum release date ofers for a prisoner ... it has been recognised consistently as a positive factor in the rehabilitation process.104

Therefore, although the power to fix a non-parole period and reviewable sentence option may be considered somewhat outside the boundaries of the current meaning of a natural life sentence, acceptance by the judiciary of such a model is a cogent possibility. This type of review may be the closest thing to a ‘litmus test’ that can be implemented in the complex sphere of sentencing for murder.

As Svensson concluded, a legislative scheme for reviewable sentences

avoids most of the dangers of existing systems, ensures the rights of the individual offender are protected by due process and goes some distance to meeting public perceptions that society must be protected from the depredations of [clearly] dangerous and violent offenders.105

B Implementing a Process of Judicial Review in New South Wales

Proceeding on the assumption that the natural life sentence is retained as the maximum punishment for murder in New South Wales, it is suggested that the achievement of suitable reform directed towards attaining more consistent, humane and equitable outcomes in sentencing for the most serious cases of murder must initially entail legislative changes.

First, section 19A of the Crimes Act should be amended to give the Supreme Court the discretionary power to affix a non-parole period to the natural life sentence up to a maximum period of 35 years. If a court declines to set a non-parole period and imposes a natural life sentence, there should be a requirement to give detailed reasons as to why it is not appropriate to set a non-parole period. In this regard, it should be noted that there is an existing general provision in section 45(1) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act for a court to decline to set a non-parole period when sentencing any offender to imprisonment for an offence where it considers it appropriate to do so:

(a) because of the nature of the offence to which the sentence relates or the antecedent character of the offender, or(b) because of any other penalty previously imposed on the offender, or

(c) for any other reason that the court considers sufficient.

The question arising from the interaction of the power to affix a non-parole period to a natural life sentence for murder and section 45 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act is whether there is a need for more rigorous legislative guidelines or whether it is preferable to rely on the formulation of specific judicial guidelines for setting the appropriate dividing line between those deserving life sentences with a prospect for release to parole and those not so deserving in the most serious murder cases. This is similar to the demarcation issue involved in the analyses of murder cases relating to drawing a clear dividing line between the most serious cases of murder deserving a natural life sentence and those very serious cases of murder deserving a lengthy determinate sentence of imprisonment. Similar issues about the potential for disparate treatment of offenders in the absence of very clear guidance for sentencing in such serious cases are raised in attempting to give substance to any new provision in this regard.

There is perhaps some amelioration of the need for rigorous and precise guidance as to the circumstances in which it is appropriate to decline to fix a non-parole period if, where a court declines to set a non-parole period for a natural life sentence, it becomes mandatory to order that the sentence be subject to incremental judicial review. This creates a new category of reviewable life sentence intended to apply to cases where it is initially considered to be inappropriate to fix a non-parole period on the basis of perceived future dangerousness or particularly heinous and/or multiple offences of murder.

The intended effect of the proposed legislative change is to make the possibility of life sentences more remote than under the present system by allowing lengthy time periods to confirm the appropriateness of this ultimate sanction. Accordingly, there is no need for a power to order or recommend that a particular offender ‘never be released’ as this option will be considered upon review in any event and eventual hope for release should not be extinguished at the initial sentencing stage. These legislative changes also aim to avoid the overwhelming ‘emotional frenzy’ associated with trials involving particularly serious and high profile murder cases. This approach, therefore, allows for more equitable and considered final outcomes, as well as providing sufficient scope for reflecting the requirements of retribution and deterrence in the actual period of imprisonment to be served.

Second, section 54(a) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act should be repealed as it currently provides a bar to the operation of Division 1 of Part 4 in relation to the sentencing of an offender ‘to imprisonment for life or for any other indeterminate period’. Sections 44 and 45 will need to apply to life sentences if discretion is to be accorded to judges to affix non-parole periods to such sentences in murder cases. Although the requirement in section 44(2) that the balance of the term of the sentence must not exceed one-third of the non-parole period would not be strictly complied with if there was to be a ‘balance of life’ term, suitable phrases could be inserted in the provisions dealing with reviewable life sentences to avoid error or anomaly. Also, consideration would need to be given to a consequential amendment by the deletion of section 54D(1)(a) so that the provisions relating to standard minimum non-parole periods apply to life sentences imposed in murder cases. The standard non-parole periods of 20 and 25 years, representing ‘the middle of the range of objective seriousness’ for murder cases, must be applied with the suggested maximum non-parole period of 35 years to determine the comparative length of any non-parole periods in the most serious cases. This is to ensure that there is internal proportionality in sentencing for murder offences across the entire spectrum of seriousness.

Third, when the initial decision is made to deal with a murder case by way of a ‘reviewable life sentence’, the judge should be required to fix a time for the first review. It is proposed the discretion should be to set a period of between 10 and 25 years. Such a time range gives adequate scope to a sentencing judge to reflect punitive considerations as well as sufficient time for any treatment and monitoring of potential rehabilitation of the offender. The provisions must have an overall emphasis on transparency and due process in setting out detailed procedures for the listing and conduct of judicial reviews of life sentences as well as providing an appropriate appeal mechanism. This is intended to remove the powers of administrative bodies, like the Parole Board, from determining the duration of imprisonment for this class of offenders. Importantly, provisions should be made for the ordering and distribution of reports and other documents prior to the review hearing as well as an express statement of the matters to be taken into account by the court at the review hearing.

C The Mechanics of the Judicial Review Process

In relation to the outcome of a review, it is expected that the life sentence would remain as the head sentence in most cases; however, a power to convert the entire sentence to a determinate one should be available consistently with the provisions relating to ‘existing life sentences’ under Schedule 1 to the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act. The review is ostensibly to determine the appropriateness of fixing a non-parole period and, consistently with the arguments presented earlier, a ceiling limit of 35 years should be set in this regard. This will allow sufficient time for periodic reviews of individuals, who might continue to represent a danger to the community after 25 years, but, with further maturation, the risk may substantially subside. The prospect of release should only be totally denied where there is a high level of certainty as to potential recidivism.

Where a non-parole period is not fixed following the initial sentence review, it is suggested that an option for the court to schedule another review no earlier than 18 months and no later than four years from that time should be provided. The power to order that the offender is never to apply for review again and to confirm the sentence as a natural life sentence could be another option upon review; however, it should only be exercised if strict criteria are satisfied. On the basis of sections 163, 169 and 170 of the Penalties and Sentences Act 1992 (Qld), legislation in this regard should require the court to form an opinion that the case involves a murder or murders of exceptional gravity or that the offender is a serious danger to the community and will remain so for an indefinite period. The court should only make this finding where it is satisfied that the available cogent evidence is of sufficient weight to justify such a finding. The onus should rest upon the prosecution to establish to a high degree of probability that the offender is a continuing serious danger to the community.106 Definitional criteria for classifying a murder or murders as ‘of exceptional gravity’ need not be provided; however, the use of the term ‘exceptional’ provides a strong implication that the murder(s) involved must be so grossly wicked or reprehensible that nothing other than punishment for the term of the person’s natural life would be proportionate to the gravity of the offence(s). A judicial guideline might be eventually formulated to provide guidance that is more substantial in this regard and this should be encouraged and promoted by the New South Wales Sentencing Council. The review would not have to be conducted by the original sentencing judge due to the prospect of lengthy time periods before initial review; however, if that judge is still available it would be highly desirable for that person to conduct the sentence review(s).

D Ordering Release after Judicial Review

A question arises as to whether responsibility for specifically ordering that an offender be released at the end of the non-parole period should lie with the judiciary so as to wholly circumvent the processes and powers of the Parole Board.

The sentencing judge would have to have regard to a structured release program including the offender’s participation in relevant pre-release programs, treatment programs, work release, day and weekend leave from prison or converting the sentence to home or hospital detention as appropriate when making orders for the date of final release from prison. Such information could clearly be made available to the court through the Serious Offenders Review Council and may be provided as part of the Council’s report to the review hearing.

Alternatively, if a determinate non-parole period were fixed by the court upon review, the case could revert to the control of the Parole Board, who currently have, and would retain, responsibility for ordering release of all convicted murderers serving wholly determinate sentences. If this occurred, an executive body would assume the power to defer release beyond the non-parole period set by the court and, where the head sentence is one of life imprisonment, this would give the Parole Board a power which the whole thrust and spirit of judicial review of life sentences is not intended to give to an executive body. The preference, therefore, is to give the sentencing judge the power to make an order directing release on a certain day, similar to that available under section 50(1) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act for imprisonment terms of three years or less.

In addition, there should be special provision for expedited review in cases involving exceptional circumstances, such as where the prisoner is dying as a result of suffering from a terminal illness or other extenuating circumstances, including but not restricted to cogent evidence of unequivocal and extraordinary rehabilitation of the offender.

E Repeal the Mandatory Life Sentence Provisions

Finally, sections 61(1) and 61(3) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act should be repealed. The result would be that it is no longer mandatory to impose a natural life sentence on a person who is convicted of murder in certain circumstances, as was suggested by the interpretation of section 6 1(1) by Greg James J in the case of R v Petrinovic.107 The existence of section 61(3) has always provided room for a strong argument that section 61(1) was never a mandatory provision; however, the repeal of both sections would clarify this perceived anomaly.

The proposed legislative reforms initially require a change in the ‘penal culture’ of the New South Wales criminal justice system.108 There needs to be a fundamental shift from the punitive ‘law and order’ political platforms of the major parties, which have promoted ‘an intensification of punishment levels and an exploitation of fear’,109 to more moderate penal policies. The penal policies should incorporate ‘proportionality’ as put forward in the ‘just deserts’ theory of punishment as the primary aim of sentencing and recognise the desirability of parsimony in punishment.

VII CONCLUSION

Clear deficiencies in the present system of sentencing for murder in New South Wales have been identified in this article, allowing the formulation of potentially beneficial proposals for reform. Qualitative empirical evidence of disparate treatment of convicted murderers in relation to the distribution of punishment for the most serious or ‘worst cases’ of murder has been starkly demonstrated through case analyses and comparisons. This disparity through lack of clear guidance as to the relative importance and weight of relevant sentencing factors has resulted in failure to apply the important ‘equal treatment’ sentencing principle. The patent consequence is that some convicted murderers are serving a sentence of life imprisonment without any prospect of early release and others are serving determinate sentences with at least the opportunity of early release for reasons which are elusive. There is no discriminating criteria or ‘litmus test’ for one outcome as opposed to the other resulting in severe inequity for certain individuals and a pressing need for reform.

Reforms have been suggested on the basis that the benefits to flow are mainly in terms of a more equitable punishment system for those convicted of the most serious crimes of murder. Base notions of revenge and absolute incapacitation should be replaced with progressive notions of managing life sentence prisoners in the custodial environment with a view to their eventual and safe release back into the community. The purpose of this is to recognise the seriousness of murder within an overall moderate and parsimonious punishment system. In addition, there must be scope for dealing with the few convicted murderers who will remain a serious danger to the community if ever released from imprisonment. The mechanism provided in this regard must seek both to enhance community safety and to promote the perspicacious observation of fundamental human rights.

In a contemporary context where it is accepted that regulation or structuring of udicial sentencing discretion will certainly be pursued by one means or another, proposals for ‘reviewable life sentences’ and the availability of non-parole periods in all cases of murder are moderate. Such proposals may appeal to both the legislature and judges concerned with reducing disparity and promoting consistency and equity in sentencing for murder, particularly at the most serious end of the spectrum of offending.

Table One – The ‘Natural Life Sentence’

Cases: January 1990–January 1997: ‘Relevant

Considerations’

Legend:

Objective Features:

Subjective Features:

B Table Two – The

‘Top’ Determinate Sentence Cases: January

1990–

January 1997: ‘Relevant

Considerations’

Legend:

Objective Features:

Subjective Features:

Endnotes

* BLegS (Macq), PhD (Newcastle); admitted to practice (NSW); Senior Lecturer, School of Law, Faculty of Business and Law, University of Newcastle.

14 This provision for a mandatory life sentence in certain murder cases was originally contained in s 43 1B(1) of the Crimes Act. That section was repealed by the Crimes Legislation Amendment (Sentencing) Act, and was re-enacted in substantially the same terms as s 61(1) of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW) (‘Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act’), which commenced operation on 3 April 2000. It has been acknowledged that this legislative provision is a selective codification of the existing common law: New South Wales Law Reform Commission, Sentencing, Report No 79 (1996) [9.13] (‘NSWLRC Report No 79’).

16 Andrew von Hirsch, ‘Law and Order’ in Andrew von Hirsch and Andrew Ashworth (eds), Principled Sentencing: Readings on Theory and Policy (2nd ed, 1998) 410, 412.

17 The killing of Anita Cobby in February 1986 and the trials and appeals from 1987 to 1989 of the five men eventually convicted of her murder brought intense media coverage and graphic descriptions of the brutality involved in the murder: see above n 6. The later killing of Janine Balding in a similar way in September 1988 involving another gang of five, including some juveniles, also attracted prolonged media attention: see R v Stephen Wayne Jamieson; R v Matthew James Elliott; R v Mathew Blessington (1992) 60 A Crim R 68.

20 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Hunt J, 12 November 1991).

22 Opened for signature 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976) (‘ICCPR’).

23 See R v Samuel Leonard Boyd (1995) 81 A Crim R 260, 269 (Gleeson CJ). The remarks of the Chief Justice that a sentence of ‘lifetime incarceration for committing four murders and one attempted murder, after a discretionary examination of the circumstances of the individual case, could [not] be described as a cruel and unusual punishment’ (at 269) came after a detailed examination of relevant case law in the United States and Canada. Chief Justice Gleeson particularly noted the case of Harmelin v Michigan, [1991] USSC 120; 501 US 957 (1991), where the United States Supreme Court held that a mandatory term of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole, imposed for possession of 650 grams or more of cocaine, did not constitute cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution: R v Samuel Leonard Boyd (1995) 81 A Crim R 260, 267. Further, it was noted that in Canada a statutory provision was held to be valid which specified, in the case of first degree murder, imprisonment for life without eligibility for parole for 25 years: R v Luxton [1990] 2 SCR 711 in R v Samuel Leonard Boyd (1995) 81 A Crim R 260, 267.

24 Section 12 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1982 provides ‘[e]veryone has the right not to be subjected to any cruel and unusual treatment or punishment’: Constitution Act 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK) c 11, s 12. See Allan Manson, ‘The Easy Acceptance of Long Term Confinement in Canada’ (1990) 79 Criminal Reports (3d) 265, in which Manson analysed the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in R v Luxton [1990] 2 SCR 711. For a more recent perspective on this issue, see Allan Manson, The Law of Sentencing (2001) 294–6.

25 Manson, The Law of Sentencing, above n 24, 269. For the current position of the Canadian Supreme Court see, R v Luxton [1990] 2 SCR 711.

26 Manson, The Law of Sentencing, above n 24, 296.

27 See the decision of the European Court of Human Rights in Staford v United Kingdom (2002) 35 Eur Court HR 1121 (‘Staford v United Kingdom’) and the decision of the House of Lords in R (on the application of Anderson) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2002] EWCA Crim 747; [2003] 1 AC 837 (‘Anderson’), which directly challenged the powers of the Home Secretary to fix tariffs for convicted murderers through private consultation with judicial officers.

30 Anderson [2002] EWCA Crim 747; [2003] 1 AC 837, 889–90.

31 Opened for signature 4 November 1950, 213 UNTS 222 (entered into force 3 September 1953). The European Convention on Human Rights has been incorporated into the domestic law of England and Wales through the Human Rights Act 1998 (UK) c 42, which commenced operation on 2 October 2000.

Generally judicial systems establish a minimum period that a life-sentence prisoner must serve before being considered for release ... In Austria and Germany a life-sentence prisoner may not be considered for release before having served 15 years. The corresponding duration in the former Czechoslovakia was 20 years ... Within Europe it is generally possible to predict the average length of a life sentence. In France a typical life sentence is 17–18 years, while in Italy it is 21 years. A life-sentence prisoner in Austria normally serves 18–20 years: [11]–[12].

For a consideration of the constitutional issues arising from the sentence of life imprisonment in Germany and a comparison to English municipal procedures and European standards generally, see Dirk van Zyl Smith, ‘Is Life Imprisonment Constitutional? – The German Experience’ (1992) Public Law 263.

34 Notably, art 14 of the ICCPR, opened for signature 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976) provides:

All persons shall be equal before the courts and tribunals. In the determination of any criminal charge against him, or of his rights and obligations in a suit at law, everyone shall be entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law ...

35 See Canadian Bill of Rights, SC 1960, c 44, s 1; Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1982, Constitution Act 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK) c 11, s 15. Section 15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms 1982 provides ‘[e]very individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability’.

36 Andrew Ashworth, Sentencing and Criminal Justice (3rd ed, 2000) 198.

42 R v Rushby [1977] 1 NSWLR 594, 598.

43 [1998] NSWSC 423; (1998) 45 NSWLR 209.

45 Chief Justice James Jacob Spigelman, ‘Opening of Law Term Dinner’ (Speech delivered at the Opening of Law Term Dinner, New South Wales Law Society, Parliament House, Sydney, 29 January 2002) <http://www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/supreme_court/ll_sc.nsf/pages/sco_speech_spigelman_290102> at 25 September 2006.

46 [2000] NSWCCA 293; (2002) 116 A Crim R 198.

49 Ashworth, above n 36, 214.

53 See especially John Anderson, The Sentence of Life Imprisonment for the Crime of Murder in New South Wales: A Contemporary Analysis of Case Law and Sentencing Principles (PhD Thesis, University of Newcastle, 2003) ch 3.2.14, 513–16, Table 3.1, 375–76, Table 3.2, 517–18.

57 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Hunt CJ at CL, 12 May 1994) analysed in Anderson, above n 53, ch 3.1.10. Further, in the later case of R v Vester Allan Fernando and Brendan Fernando (1997) 95 A Crim R 533, involving two Aboriginal cousins aged 27 and 25 years respectively at the time of sentence, the aspect of relative youth considering life expectancies of 49–50 years was accorded no effective weight in the final imposition of natural life sentences: at 544 (Abadee J). The case of R v Stephen Wayne Jamieson; R v Matthew James Elliott; R v Mathew Blessington (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Newman J, 18 September 1990) involved two very young offenders, Elliott aged 16.5 years and Blessington aged approximately 15 years at the time of the murder offence; however, this fact did not weigh so heavily to prevent the sentencing judge from making a ‘never to be released’ recommendation in respect of all offenders.

58 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Newman J, 17 August 1993) analysed in Anderson, above n 53, ch 3.2.8.

59 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Mathews J, 21 May 1991) analysed in Anderson, above n 53, ch 3.2.11, where the extreme youth of the prisoner together with his disturbed state of mind at the time of the murder were accorded substantial weight in mitigation of punishment.

60 More recently, in the case of R v Christopher Andrew Robinson [2000] NSWSC 972 (Unreported, Adams J, 19 October 2000), Adams J held that the extreme youth of the prisoner, being less than 18 years of age at the time of commission of the murder, prevented the case from falling into the category of ‘worst class of case’ and prevented the operation of s 61 of the Crimes (Sentencing Procedure) Act, so that a natural life sentence was avoided on this basis alone. In this regard, Adams J commented, before imposing a very lengthy term of 45 years imprisonment on Robinson, that ‘this is a legislative recognition of the significance that has always been placed by the community and the courts on the youth of an offender who comes to be sentenced, even for very serious crimes. The heaviest penalty is reserved, unless the circumstances are very exceptional, for mature adults’: at [41].

62 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Newman J, 16 October 1992) analysed in detail in Anderson, above n 53, ch 3.1.5.

63 R v Cameron (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Newman J, 16 October 1992) 16.

64 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Finlay J, 28 February 1994) analysed in detail in Anderson, above n 53, ch 3.2.4.

65 R v Richardson (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Finlay J, 28 February 1994) 9.

67 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Finlay J, 21 March 1995) analysed in detail in Anderson, above n 53, ch 3.2.3.

68 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Court of Criminal Appeal, Carruthers, Finlay and Badgery-Parker JJ, 4 November 1994) analysed in detail in Anderson, above n 53, ch 3.1.6.

69 R v Twala (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Sully J, 18 March 1993) 14.

70 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Hidden J, 13 December 1996) analysed in detail in Anderson, above n 53, ch 3.2.2.

72 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Wood J, 29 November 1991).

73 (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Hunt CJ at CL, 27 July 1996).

74 R v Mrish (Unreported, Supreme Court of New South Wales, Hidden J, 13 December 1996) 8.