University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

JUVENILE SEX OFFENDING:

ITS PREVALENCE AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE RESPONSE

KATE WARNER[*] AND LORANA BARTELS[**]

The public perception of sex offenders tends to be of predatory stranger rapists and child molesters.[1] A typical child molester is perceived to be the predatory child sex offender who lurks around schoolyards and playgrounds.[2] The public exposure of child exploitation networks or ‘rings’ which produce and share child pornography reinforces the stereotype of the classic child molester as a predator who targets strangers. Publicity about institutional child sexual abuse, such as that emanating from the current Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse,[3] reflects a shift in focus away from stranger danger towards abuse by adult familiars such as priests, teachers, carers or supervisors of children. However, it is not widely appreciated that a considerable proportion of sex offending is perpetrated by other children or adolescents, including members of the victim’s family.[4] This is largely obscured by court data and victim surveys. There is accordingly a danger that the issue of responding appropriately to the sexual offending of juveniles could be lost in general discussions of both youth crime and child sexual abuse.[5] Whilst there is some literature on juvenile sex offending, its focus is generally on offender profiles, explanations for offending and predictors of reoffending.[6] There is a void in the literature when it comes to how juvenile sex offending is dealt with in the criminal justice system.[7] A notable exception is Daly et al’s Sexual Assault Archival Study,[8] which examined a sample of juvenile sex offenders in South Australia and compared conference and court outcomes, analysed sentencing remarks in a sample of cases and explored the dynamic of conferencing in sexual and family violence cases. Nevertheless, general discussions of both sentencing for sex offences and the criminal justice response to young offenders tend to pay scant attention to the issue. Accordingly, this article aims to fill a gap in the literature by focusing on the prevalence of sexual offending by juveniles and the criminal justice response to it in the wider context of juvenile offending and sex offending in general. The article’s broader aim is to ensure that the issue of juvenile sex offending is not ignored and opportunities for intervention and prevention are not lost.

The article has four central parts. First, we review what is known about the incidence of sex offences perpetrated by juveniles and place this in the context of youth and sex offending in general. Secondly, we review aspects of the substantive Australian criminal law that relate to young sex offenders. Thirdly, we give an overview of the legal framework governing juvenile justice and explain where sexual offences fit within it. The fourth section focuses on sentencing practice. It gives data on sentencing outcomes in juvenile sex offence cases and provides an overview of appellate guidance in relation to sentencing juvenile sex offenders. Finally, we conclude that more research is needed on the way juvenile sex offenders are dealt with by the criminal justice system. In particular, it is important to explore and debate the appropriate response to sexual offending by juveniles. The issue should not be neglected in favour of an exclusive focus on adult sex offenders. Neglect is a real risk when juvenile sex offenders fit neither the stereotype of a typical juvenile offender nor a typical sex offender.

Only a small proportion of offences that are dealt with by Australian courts are juvenile sex offences. In fact, there were only 634 defendants finalised in the Children’s Courts in 2012–13, accounting for 0.1 per cent of the 561 554 defendants finalised in Australian courts. In 2012–13, defendants finalised for sex offences represented two per cent of all defendants finalised by the Children’s Courts.[9] By way of comparison, sexual offences accounted for 0.8 per cent of defendants’ matters finalised in Magistrates Courts and 17.9 per cent in the higher courts.[10] Moreover, court data show that defendants who have been adjudicated for sexual assault offences tend to be older than defendants for all other offence categories.[11] These facts could reinforce the perception that juvenile sex offending is an unusual form of sexual offending. However, court data are known to be an inaccurate measure of crime, as apparent differences in offending patterns may be due to differences in reporting, policing and prosecution practices. This section will therefore examine other ways of assessing the prevalence of crime, namely victim surveys and recorded crime statistics, to see what they reveal about the prevalence of sex offences perpetrated by juveniles. It is acknowledged that there are difficulties in measuring the prevalence of crime, and that for sex offences, the ‘dark figure’ is particularly difficult to illuminate.[12]

Because personal crimes are notoriously under-reported, victim surveys are an important means of examining the prevalence of this form of offending, as well as helping to develop a clearer understanding of who commits these offences. Victim surveys have done much to address common myths and misperceptions about child sexual assault, such as the misperception that most child sex offenders are paedophiles and that child sex offenders target strangers.[13] However, victim surveys in Australia do not collect data on sexual assaults committed by children. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (‘ABS’) Personal Safety Survey, which explores respondents’ experiences of physical and sexual violence and abuse, defines child sexual abuse as ‘[a]ny act by an adult involving a child (before the age of 15 years) in sexual activity’.[14] The annual national Crime Victimisation Survey interviews respondents aged 18 and over about sexual assaults committed in the last 12 months and therefore collects little information on child sexual assault.[15] When profiles of sex offenders are constructed on the basis of ABS victim surveys, child and adolescent offenders who offend against other children are therefore omitted from the picture.[16] This obscures the fact that that sex offenders and child sex offenders in particular can themselves be other children. Given that Australian victim surveys are unhelpful in relation to the prevalence and nature of youthful sex offending, reliance on other sources is necessary.

Australian police crime statistics suggest young people are over-represented in detected crime compared with adults, with 15–19 year olds more likely to be processed by police for the commission of a crime than members of any other population group.[17] In 2012–13, the offender rate (per 100 000 estimated resident population) for 10–14 year olds was 1112, while the overall average offender rate was 1958.[18] The highest offender rate was for offenders aged 15–19, at 5232. It is of interest, however, that the offender rate for sex offences for 10–14 year olds was 35.1, higher than the overall rate of 30.1. Furthermore, the rate for 15–19 year olds was 59.9, almost twice the general rate for this offence type, and much higher than the next highest rate, at 39.5 per 100 000 for offenders aged 20–24. This indicates that although young offenders are unlikely to commit sex offences, compared with other forms of offending, offenders aged 15–19 commit sex offences at twice the rate of the general population. Furthermore, 10–14 year olds, an age group one would not generally regard as being the peak of sexual offending, are on par with the general population (35.1 and 30.1 per 100 000 respectively).

Richards states that ‘very serious offences (such as homicide and sexual offences) are rarely perpetrated by juveniles’.[19] This appears to be the case in terms of the number of sexual offences committed as a proportion of youth offending overall. In 2012–13, there were 54 793 offences recorded as committed by 10–17 year olds, of which 1089, or approximately two per cent, were sexual assault offences.[20] However, this does not indicate clearly the extent to which juveniles are responsible for all offending of this nature. Over this period, there were 6004 sexual assault offences recorded in Australia – and juveniles aged 10–17 were responsible for approximately 18 per cent of these offences.[21] It appears, therefore, that although sexual offending comprises only a small proportion of youth offending (and a smaller proportion still of all recorded crime), juveniles account for a relatively high proportion of sexual offences committed. This proposition is explored further through the data in Table 1.

Table 1: Number and offender rate for sex offences, by age and gender

|

Males

|

Females

|

|

Age

|

Number of offenders

|

Offender rate (per 100 000)

|

Number of offenders

|

Offender rate (per 100 000)

|

|

10

|

13

|

9.2

|

0

|

0.0

|

|

11

|

21

|

14.8

|

6

|

4.4

|

|

12

|

52

|

36.3

|

10

|

7.3

|

|

13

|

114

|

79.4

|

43

|

31.4

|

|

14

|

185

|

128.3

|

45

|

32.9

|

|

15

|

198

|

136.2

|

48

|

34.8

|

|

16

|

175

|

118.8

|

19

|

13.6

|

|

17

|

149

|

99.1

|

11

|

7.7

|

|

18

|

138

|

90.1

|

8

|

5.5

|

|

19

|

126

|

81.3

|

4

|

2.7

|

|

Total youth offenders – sex offences

|

1171

|

79.9

|

194

|

13.9

|

|

Total all offenders – sex offences

|

5681

|

57.4

|

312

|

3.1

|

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4519.0 – Recorded Crime – Offenders, 2012–13 (27 February 2014), table 6 <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4519.0Main+Features12012-13?OpenDocument> .

The ABS data on offender numbers and offending rates by age[22] are particularly instructive. As set out in Table 1 above, the peak age for sexual offending is 15, with such offenders accounting for almost 17 per cent of all sex offending by males aged 10–19 and almost 25 per cent of such offences by females. Perhaps more striking still, 15 year old males were responsible for over three per cent of all male sexual offending reported, while 15 year old females accounted for over 15 per cent of female sexual offending across all age groups. The male offender rate for sexual offences for 15 year olds was almost 2.4 times the overall sexual offending rate (136.2 versus 57.4 per 100 000); for 15 year old females, it was over 11.2 times the overall sexual offending rate (34.8 versus 3.1). Males aged 10–17 accounted for almost 16 per cent of all recorded sex offences. Surprisingly, however, 10–17 year old females represented over 58 per cent of all sexual offences committed by females. Accordingly, there is not only a lack of information about juvenile sex offending generally, but about the significant extent to which such offences are committed by juvenile females as a proportion of female sexual offending.[23]

It is acknowledged that detected crime is not an accurate measure of actual offending rates and there are a number of plausible reasons why young people may be more likely to be apprehended by police than adults, such as that they are less experienced and their offending is more often in groups and therefore more visible.[24] Moreover, offences for which they are most over-represented, such as burglary and theft, have higher reporting rates.[25] It is also usually accepted that the crimes committed by young people are those at the least serious end of the spectrum.[26] It may therefore be the case that reported sexual offences committed by young people are less serious than those committed by adults, but this is not apparent from the data. The fact remains, however, that in terms of recorded crime, over 18 per cent of alleged sex offenders in 2012–13 were under the age of 18.[27]

Child protection data are another possible source of information on juvenile sex offending. However, while the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare includes national data on notifications of child sexual abuse, there is no information reported on perpetrators. Data from sex assault services is another possible source that could clarify the prevalence of juvenile sex crime, although information on the age of perpetrators is not routinely reported from these sources. However, one study from New South Wales (‘NSW’) reported that males aged under 16 were the assailants in 16.2 per cent of cases of initial presentations to sexual assault services for child sexual assault.[28]

Some international sources suggest that the prevalence of sexual abuse committed by young people is much higher than Australian recorded crime data indicate and that offences by young people account for up to 50 per cent of offences against children and 30 per cent of rapes of adolescent girls and women.[29] Pratt and Miller cite United States (‘US’) studies which indicate that approximately 30–60 per cent of childhood sexual abuse is perpetrated by other children and young people.[30] This is supported by United Kingdom (‘UK’) national surveys which have found that two-thirds of contact sexual abuse reported in respect of 0–17 year olds was committed by peers.[31]

In summary, the omission of sex offences perpetrated by juveniles from victim surveys contributes to obscuring its prevalence in Australia. Recorded crime statistics suggest that a significant proportion of sex offending (18 per cent) is committed by juveniles, even though it only accounts for a small proportion (two per cent) of juvenile offending. That juveniles account for a significant proportion of sex offending is supported by international data. The next section of the paper examines how the criminal law has approached the criminal responsibility of juvenile sex offenders.

The substantive criminal law has adopted complex and at times contradictory responses to young sex offenders. The perennial problem in sexual offences of what is and is not consensual[32] is compounded by questions about the age of criminal responsibility, the age of consent and the appropriate boundaries of the criminal law. The traditional age of criminal responsibility at common law was seven, although children as young as six years of age were imprisoned in Australia until the middle of the 19th century.[33] Between the ages of seven and 14, the principle of doli incapax operated, so that a child under 14 could only be found criminally responsible if the prosecution could prove that he or she had the capacity to know that their conduct was wrong.[34] The common law also presumed that a male under the age of 14 was incapable of sexual penetration.[35] At the same time, the law prescribed an age of consent, the minimum age at which a person was competent to consent to sexual acts. In 13th century England this was 12 but by the end of the 19th century it was 16,[36] and in some Australian states it was raised to 18.[37] While the age of consent has traditionally been justified in terms of protecting young people from predatory sexual exploitation by adults, it was also about the regulation of teenage sexual activity, with prosecutions in some jurisdictions of young men who were themselves under the age of consent and of under-age girls for aiding and abetting.[38]

Modern law in the second decade of the 21st century retains many vestiges of the old common law. In Australia, the Commonwealth, states and territories have progressively legislated to adopt a standardised minimum age of criminal responsibility of 10 and there are varying formulations of the doli incapax presumption for children aged from 10 to 14.[39] The minimum age of criminal responsibility is now 10 in the UK, but is higher in many other countries; for example, it is 12 in Canada, 13 in France and 14 in Germany.[40] The conclusive presumption that a male under the age of 14 is incapable of having sexual intercourse has been abolished or significantly reduced (for example, in Tasmania it has been reduced to apply only to a male under the age of seven). The age of consent is now 16 in most Australian jurisdictions,[41] although there are significant differences in the availability of similar age consent defences. The most common position is for a permissible age differential of two years, provided the under-age person is at least 12.[42]

The availability of a similar age consent defence in cases of consensual sex between adolescents is controversial. Rather than liberalising the laws which criminalise the sexual conduct of consenting teenagers, some jurisdictions have preferred to leave the matter to be determined by prosecutorial discretion.[43] There are strong arguments of principle against such a position. There is evidence that a considerable proportion of adolescents and teenagers under the age of consent engage in consensual sexual acts and that criminalising such behaviour is an inappropriate response which can have negative consequences in terms of inhibiting access to and the provision of health care and contraception. Relying upon prosecutorial discretion to remedy the overreach of the criminal law is contrary to the rule of law.[44] Determining who is the offender and who is the victim is also difficult in the context of consensual teenage sex.[45] On the other hand, the criminal law has an important role in protecting young and vulnerable children from sexual exploitation and abuse. Drawing the line between childhood play or consensual teenage sex on the one hand and sexual exploitation or abuse on the other can be difficult.

In general the law treats children who offend differently from adults. In accordance with the United Nations’ Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (‘Beijing Rules’), all Australian jurisdictions have sets of laws specifically applicable to the administration of juvenile justice which are designed to meet the varying needs of juvenile offenders whilst protecting their basic rights. Similar to international trends in the common law world, the youth justice system has experienced an ideological shift from a ‘welfare model’, with an emphasis on the needs of the young person and rehabilitation and treatment, to a justice model, with more focus on accountability and proportionate punishment.[46] However, this shift has only been partial and court practices and legislative sentencing principles suggest a continued interest in a rehabilitative approach.[47] Moreover, diversionary practices aligned with restorative justice have had a strong influence on juvenile justice policy and practice[48] so that current juvenile justice frameworks include elements of welfare, justice and restorative justice models.[49]

In accordance with article 40.3 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (‘CROC’) and rule 11 of the Beijing Rules, which create a preference for diversion over formal judicial proceedings, there is a strong emphasis on diversion in each of the Australian jurisdictions. Police cautioning is one of the main methods used to divert young people away from more formal processing. Cautioning may be informal or formal and may be regulated by legislation or administrative guidelines.[50] In Victoria, for example, where cautions are governed by operational instructions rather than legislation, police will only consider a caution for sexual or related offences in exceptional circumstances and will obtain advice as to suitability from the Manager of the Sexual Crimes Squad.[51] A formal caution typically involves an admission by the offender and a warning given by a police officer to the young offender at the police station in the presence of a family member. Cautioning rates differ between jurisdictions and national data are not available. Moreover, informal cautions are not reflected in police cautioning data. In Victoria, for example, in 2009–10, about 25 per cent of young alleged offenders processed by the police received a formal caution.[52]

To continue using Victoria as an example, the most common alleged offence was theft from shops (57.7 per cent) while sex offences accounted for 5.8 per cent of alleged offences.[53] Daly et al’s South Australian archival study of youths charged with sexual offences and finalised between 1995 and 2001 revealed that 10 per cent of cases were dealt with by caution.[54] These figures are now somewhat dated but this appears to be the only Australian study which charts the flow of juvenile sex offences through the criminal justice system.

The development of juvenile conferencing in Australia has been influenced by New Zealand’s family group conference model and by restorative justice theory. Most jurisdictions have legislated for diversionary conferences.[55] Typically the decision to refer a matter to court or a conference is made by a police officer. Victoria is an exception, as its Youth Justice Group Conferencing Program only takes referrals from the Children’s Court of Victoria. This is a pre-sentence restorative justice option which allows the court to defer sentence of a child for up to four months to enable a group conference to occur.[56]

The form of conference is basically the same in each jurisdiction, although there are jurisdictional differences in the kinds of offences that are conferenced, the volume of activity that is engaged in through conferencing, the upper limit on conference outcomes and other differences.[57] In NSW and Western Australia, most sexual offences cannot be referred to a conference.[58] In some other jurisdictions, by contrast, it is theoretically possible for serious sexual offences to be referred.[59] For example, in Tasmania, the police can refer rape or aggravated sexual assault to a conference if the alleged offender is under the age of 14, and indecent assault and sexual intercourse with a young person can be referred to a conference in all cases.[60] However, in practice, it is unusual for sex offences cases to be referred for conferencing. In fact, South Australia appears to be the only Australian jurisdiction to routinely refer juveniles charged with sexual offences to a conference. Indeed, Daly et al claimed that very few countries in the world do so,[61] although 20 per cent of young people in their study who were charged with a sex offence were dealt with by referral to a conference.

Daly et al compared the outcomes of court and conferences and concluded that conferences have the ‘potential to offer victims a greater degree of justice than court’[62] and that the conference penalty regime may produce better outcomes for the offender and the community.[63] Daly’s findings suggested that conference outperformed courts on measures relating to the victim. These findings are in turn supported by the finding that conference cases had a greater likelihood of an admission of the offence (which provided some degree of vindication) whereas the charges in half the court cases were dismissed or withdrawn, with the potential for victim disappointment, disillusionment or anger. Findings supporting the claim that conference cases produced better outcomes for the community were that first-time offenders were more likely to be referred to a specialist counselling program (Mary Street) and less likely to reoffend. [64] However, her claims have been challenged by Cossins, who contests the potential of restorative justice processes to produce superior outcomes for victims, and argues instead for radical reforms to the trial process.[65]

Specialised children’s courts (variously designated as the ‘Children’s Court’, ‘Youth Court’ or ‘Juvenile Court’) are modified courts of summary jurisdiction with enlarged powers to deal with matters summarily. Typically, their jurisdiction covers most but not all criminal offences committed by young people under the age of 18 (except in Queensland, where the cut-off is 17).[66] In NSW, the Children’s Court has jurisdiction over sexual assault (that is, rape),[67] aggravated indecent assault and indecent assault, but not over the most serious sexual offences, such as aggravated sexual assault[68] or assaults with intent to have sexual intercourse.[69] In Victoria, the Children’s Court has jurisdiction over all sexual offences[70] unless the Court considers that the matter is unsuitable to be dealt with summarily given the existence of exceptional circumstances.[71] In Queensland, the Children’s Court has jurisdiction over rape, or carnal knowledge of a child under 12.[72] In South Australia, the Youth Court has broad jurisdiction, although a youth may be dealt with in the same manner as an adult if the Court so determines because of the gravity of the offence.[73] According to Bouhours and Daly, this rarely happens; from 1999 to 2004, no sexual offences were transferred from the Youth Court to an adult court.[74] The Western Australian Children’s Court has exclusive jurisdiction to hear and determine offences committed by a child.[75] In Tasmania, serious sexual offences (such as rape and aggravated sexual assault) must be dealt with in the Supreme Court where the offender is at least 14 years of age.[76] In the Australian Capital Territory (‘ACT’), the jurisdiction of the Children’s Court extends to any offence not carrying a maximum penalty of life imprisonment,[77] while the Northern Territory Youth Justice Court has jurisdiction over ‘all charges in respect of summary offences or indictable offences allegedly committed by a youth’.[78] It should be noted that regardless of the jurisdiction of children’s courts, young persons may elect to have some indictable offences determined by a jury,[79] but it seems that this happens very rarely, at least in Victoria.[80]

To summarise the above discussion, children’s courts in Australia have a broad jurisdiction to try offences, including sexual offences. In Tasmania, however, charges of rape are outside the jurisdiction of the juvenile justice system, at least for defendants over 14, and more serious rapes are excluded in NSW.

The problem of the gap between the large number of cases of sexual assault reported to the police and the small number resulting in conviction is one which the criminal justice system has struggled to address for decades in many Western countries.[81] While attrition seems greatest at the police stage, it is also high once cases get to court.[82] In the discussion of this issue the focus tends to be on cases where the accused is an adult but it is likely that the same phenomenon applies in relation to juvenile accused.

The table below presents Australian Children’s Courts’ data on the finalisation of defendants whose cases were adjudicated or withdrawn, where the principal offence was a sexual offence, in comparison with finalisation for all offences in total and in comparison with adult defendants in the higher courts.

Table 2: Defendants finalised, principal offence by method of finalisation, Children’s Courts and Higher Courts, 2011–12

|

|

Acquitted (%)

|

Proven guilty (%)

|

Total adjudicated (%)

|

Withdrawn (%)

|

Total* (%)

|

|

Children’s Courts

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sex offences (n=574)

|

10.5

|

50

|

60.5

|

21.4

|

81.9

|

|

All offences (n=33,605)

|

3.9

|

78.9

|

82.9

|

9.6

|

92.5

|

|

Higher Courts

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sex offences (n=2,879)

|

17.7

|

62.4

|

80.1

|

18.9

|

99

|

|

All offences (n=15,473)

|

7.5

|

78.5

|

86.1

|

12.5

|

98.6

|

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4513.0 – Criminal Courts, Australia, 2011–12 (14 February 2013), Children’s Courts Australia table 5, Higher Courts table 5 <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/

Lookup/4513.0Main+Features12011-12?OpenDocument>.

* total less than 100% because it includes other non-adjudicated matters such as transfers to other courts and non-court agencies and unknown methods of finalisation.

Table 2 shows that more than one fifth of sex offence cases in the Children’s Courts in 2011–12[83] (21.4 per cent) were withdrawn by the prosecution. An additional 18 per cent were also not adjudicated – they were either transferred to other courts or a non-court agency, for example. The proportion of sex cases withdrawn was more than double the proportion withdrawn for all offences in total (9.6 per cent). A similar proportion of sex offence cases was withdrawn in the higher courts (18.9 per cent) but very few additional cases were finalised by non-adjudication (<1 per cent). In the Children’s Courts, therefore, sex offences were more likely to result in acquittals than for offences overall, a pattern which is a common finding for sex offences generally.

In Daly’s Sexual Assault Archival Study, approximately 44 per cent of the court cases (in the South Australian Children’s Court) were dismissed or withdrawn.[84] She notes that this has implications for victims, who received no recognition of their victimisation[85] and for offenders, who lost the chance of being considered for treatment.[86] In relation to the data presented in Table 2, it is not known if any of the juvenile defendants whose cases were withdrawn by the prosecution or otherwise not adjudicated did in fact receive some kind of treatment or other informal follow-up. Moreover, it is unclear if not adjudicating the matter and avoiding the possibly stigmatising effect of court proceedings is or is not in the public interest in the long term. It is likely that some of the charges involved consensual sexual activity. Prosecution agencies may therefore have determined that it would not be in the interests of justice to pursue the matter. And more generally, they may prefer a light touch approach when juveniles are charged with sex offences to avoid the implications and stigma of a conviction. Judicial attitudes may also be sympathetic to such an approach. This is supported by a 2012 ACT case, where the judge refused to convict a man who had pleaded guilty to having a consensual sexual relationship with a 13 year old girl when he was 17, noting that the ‘legal and social consequences for [the offender] of recording a conviction against him in [this] case far outweigh the requirements of punishment, denunciation and deterrence, both personal and general’.[87]

The sentencing options available to the Children’s Courts differ in type and scale from those applicable to adults. They also differ among jurisdictions. Typically they range from dismissing the charge with or without a reprimand, through fines, probation and community service, to imposing a period of detention, which may be suspended. Typically there are also provisions in relation to whether or not a conviction can be recorded and the criteria for determining this when there is a discretion. In most jurisdictions, there is a legislative hierarchy of sanctions which sets out the available penalties from the least to most punitive disposition (or vice versa). In some jurisdictions (for example, NSW and Victoria), there is a provision which prevents the court from imposing a more severe sanction if a less severe order is appropriate.[88] Courts may also refer matter to a community conference in some jurisdictions.

The relevant sentencing principles and purposes differ from the adult criminal justice system. To understand how they operate in relation to sex offences and to give context to the discussion of sentencing practice in the next section, it is necessary to explain these principles in a little detail. In the adult system, the statutory purposes of sentencing typically list one or any combination of: punishment, general and specific deterrence, denunciation, protection of the community and rehabilitation.[89] By contrast, in Victoria’s Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (the ‘CYF Act’) section 362(1) exemplifies the sentencing principles that the Children’s Court must apply when sentencing a young offender:

(a) the need to strengthen and preserve the relationship between the child and the child’s family;

(b) the desirability of allowing the child to live at home;

(c) the desirability of allowing the education, training or employment of the child to continue without interruption or disturbance;

(d) the need to minimise stigma to the child resulting from a court determination;

(e) the suitability of the sentence to the child;

(f) if appropriate, the need to ensure that the child is aware that he or she must bear a responsibility for any action by him or her against the law; and

(g) if appropriate, the need to protect the community, or any person, from the violent or other wrongful acts of the child.

(a) Rehabilitation

Whilst not expressly referring to rehabilitation, the first four principles’ focus in section 362(1) is forward-looking and rehabilitative rather than punitive. There are similar provisions in other jurisdictions.[90] This justifies the assertion made by the courts that, notwithstanding any statutory changes that include acceptance of responsibility and protection of society as considerations in sentencing juveniles, rehabilitation remains a more important consideration.[91]

(b) Accepting Responsibility

The sixth principle in section 362(1)(f) of Victoria’s CYF Act, which aims to ensure the offender accepts personal responsibility for the crime, reflects the influence of the justice model and is a common inclusion in Australian juvenile justice legislation.[92]

(c) Community Protection and Deterrence

The need, where appropriate, to protect the community from the violent or other wrongful acts of the child (see section 362(1)(g) above) is referred to in several jurisdictions.[93] These provisions are clearly concerned with the protection of the community through specific deterrence, that is, deterrence of the particular child offender.[94] Presumably, protection of the community may in some cases require incapacitation of a particular child offender. Whether or not general deterrence is a relevant consideration differs between the jurisdictions. In Victoria, the Court of Appeal has emphatically rejected reliance on general deterrence in sentencing children on the basis of the construction of the CYF Act. General deterrence has been held to be ‘entirely foreign’ to the scheme of section 362(1) of the Act because it directs attention to what will deter, or prevent the particular child from engaging in violent or other wrongful acts.[95] In South Australia too, general deterrence is not a relevant consideration[96] unless the child is being dealt with as an adult.

In NSW, where the legislation makes no express reference to the protection of the community, it is accepted that considerations of general deterrence and punishment are relevant in sentencing juvenile offenders but are generally of less weight than rehabilitation. In KT v The Queen,[97] the Court of Criminal Appeal explained that the protection of society may require that more weight be given to retributive and deterrent elements of sentencing when a young offender conducts himself or herself as an adult and commits an offence of great violence or gravity. In Western Australia, where protection of the public is a general principle of juvenile justice, the Court of Appeal has held that although rehabilitation is a dominant consideration, both general and specific deterrence ‘still have a role to play, albeit, generally, a tempered role’.[98] Similarly, in the Northern Territory, Martin CJ has stated:

Rehabilitation is always a significant factor when dealing with young offenders ... However, as a matter of sentencing principle and community expectation, there are times when the offending by a young person ... is so serious that considerations of youth and rehabilitation must take second place to the elements of punishment, denunciation and general deterrence.[99]

In NSW, the principles in section 6 of the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 (NSW), which is fairly similar to section 362(1) of the Victorian CYF Act, apply even when the matter is being dealt with by a superior court. More commonly, the principles applicable to adult offenders apply when a child is being sentenced in a superior court but courts may have the discretion to sentence the young person under the relevant juvenile justice legislation.[100] In Victoria, the sentencing principles in the CYF Act apply to superior courts if the offence for which the offender was convicted was within the jurisdiction of the Children’s Court, but in other cases in superior courts, the principles applicable to adult offenders apply.

The above principles apply in the case of sex offences in Australia, at least where the matter is heard in a Children’s Court or the judge in a superior court elects to apply the youth justice legislation or it applies generally (as in NSW). Courts are also guided by appellate decisions that deal specifically with sentencing youths convicted of sexual offences. This section presents recent data on sentencing patterns for juvenile sex offences, before giving an overview of reported appellate decisions on this subject.

There were 347 defendants who had a sexual offence as their principal adjudicated offence in the Children’s Court in 2011–12.[101] Of these, 60 (17 per cent) were acquitted and 287 (83 per cent) were proven guilty.

|

Sentencing outcomes

|

Sex offences (%)

|

All offences (%)

|

|

Custody in a correctional institution

|

15.7

|

6.1

|

|

Custody in the community

|

5.9

|

1.9

|

|

Fully suspended sentence

|

8.4

|

2.7

|

|

Total custodial orders

|

30.0

|

10.7

|

|

Community supervision/work orders

|

43.9

|

28.3

|

|

Monetary orders

|

2.1

|

15.2

|

|

Other non-custodial orders

|

24.0

|

45.8

|

|

Total non-custodial orders

|

70.0

|

89.3

|

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4513.0 – Criminal Courts, Australia, 2011–12 (14 February 2013) <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4513.0Main+Features12011-12?OpenDocument> , Children’s Courts Australia table 8.

As set out in Table 3, the most common sentencing outcome was a community supervision or work order (44 per cent), followed by ‘other’ non-custodial orders (24 per cent). Custody in a correctional institution, fully suspended sentences and custody in the community accounted for 16, eight and six per cent respectively. It is clear that the sentencing patterns for sex offences are unlike sentencing patterns for other offences, with offenders much more likely to be sentenced to correctional custody (16 versus six per cent), and custodial sentences accounting for 30 per cent of all sentences imposed, compared with an average across all offences of 11 per cent. Offenders were also much more likely to receive community supervision/work orders (44 versus 28 per cent) and less likely to receive monetary orders (two versus 15 per cent) or ‘other non-custodial orders’ (24 versus 46 per cent).

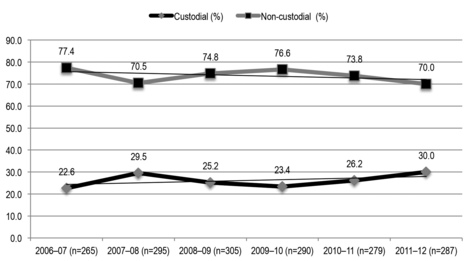

Figure 1 sets out sentencing patterns for sex offences in the Children’s Court between 2006–7 and 2011–12. As can be seen, the use of custodial orders ranged from 23 to 30 per cent, and demonstrated a slight upward trend over the period. Non-custodial orders showed a corresponding slight decline and ranged from 70 to 77 per cent.

Figure 1: Sentencing outcomes in the Children’s Courts for sex offences, 2006–7 to 2011–12

Source: Adapted from Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4513.0 – Criminal Courts, Australia, 2011–12 (14 February 2013), Children’s Courts Australia, Table 9 <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/

4513.0Main+Features12011-12?OpenDocument>.

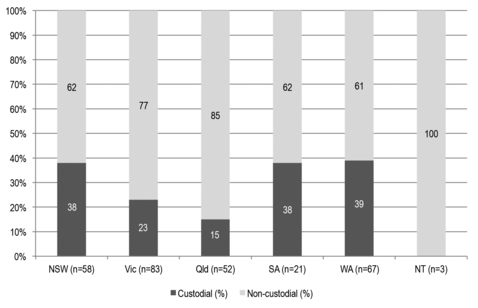

Figure 2 sets out the custodial and non-custodial sentences for sex offences in the children’s courts by jurisdiction in 2011–12 (excluding Tasmania and the ACT where there were no such sentences imposed). The small numbers in the Northern Territory (n=3) should also be treated with caution, but it is interesting that this represents a very different pattern from the other courts, with no custodial sentences imposed. Custodial sentences were also rare in the Queensland children’s courts (15 per cent), compared with 38–9 per cent in NSW, South Australia and Western Australia. Children’s Courts do not publish sentencing remarks so it is not possible to flesh out the sentencing data with an analysis of sentencing remarks in cases of sex offences.[102]

Figure 2: Sentencing outcomes in the Children’s Courts, by jurisdiction

Source: Adapted from Table 18 of each jurisdiction’s dataset: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4513.0 – Criminal Courts, Australia, 2011–12 (14 February 2013) <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/

Lookup/4513.0Main+Features12011-12?OpenDocument>.

This section gives an overview of the courts’ appellate guidance when sentencing juvenile offenders for sex offenders. It is not an exhaustive review, but is designed to give a flavour of the courts’ approach. A case search for appellate guidance in relation to the sentencing of juvenile sex offences revealed nothing from Victoria or South Australia. Interestingly, in these two jurisdictions, the Children’s Courts have the widest jurisdiction over sex offences.

In NSW, as explained above, the Court of Criminal Appeal has held that if a young offender conducts himself (or herself) in a way that an adult would, deterrence and retribution become more significant. This requires an assessment of the maturity and conduct of the young offender as well as the degree of violence and gravity of the offence. The violence of the offence, does not of itself, necessarily establish that the youth is acting as an adult.[103] In a case of aggravated sexual assault, the question will be whether the young person has conducted him/herself in a way that an adult would, in which case deterrence and retribution become more significant. In BP v The Queen,[104] a case where the young offender raped a young woman aged 19 just before his 17th birthday, Hodgson JA cautioned against too readily discounting an offender’s youth on the basis that the offender has engaged in adult behaviour. In his view, the circumstances of the offence (it was committed whilst the offender was drinking with friends in a group) suggested emotional immaturity and under-developed impulse control were likely to be contributing factors.[105] Justice Johnson, however, considered the offender’s youth and immaturity were largely neutralised by the warnings which he had received from his prior convictions for similar offences and the subsequent counselling and reinforcement provided to him.[106] Ultimately, this difference of opinion made little difference to the sentence imposed by the Court – a non-parole period of three years and a balance of two years.[107] The challenge of reconciling the seriousness of the offence with the offender’s youth was noted in CM v The Queen.[108] In that case, the sentence of 10.5 years (with a non-parole period of 6.5 years) for a prolonged violent and degrading attack in which a 26 year old woman was bashed with a piece of wood and raped was upheld, and the argument that the sentence had not paid sufficient regard to the sentencing principles in section 6 of the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 (NSW) was rejected.

A different category of case is where the victim is a child under the age of 12 and the offender an adolescent. In such cases, despite the seriousness of the offences (penetration of a child under the age of 12), the Court of Criminal Appeal has quashed longer sentences of imprisonment and imposed a short non-parole period followed by somewhat longer parole periods with treatment conditions. For example, in AEL v The Queen,[109] the 13 year old offender’s victims were his younger siblings. In quashing a non-parole period of 18 months with a further term of three years and nine months and substituting a non-parole period of some 12 months (backdated) with a further term of about 18 months, the Court acknowledged the seriousness of the offences, but noted that ‘they should be understood as aberrant behaviour engaged in by a troubled boy in early adolescence’.[110] What was needed was a sentence which provided for continuation of a program involving close supervision and attention to the offender’s development so that he could ultimately function as a responsible member of the community. His release to parole was ordered as soon as arrangements could be made for his accommodation in a residential youth program with conditions that he accept the direction and supervision of the Department of Juvenile Justice. Interestingly, the Court of Criminal Appeal noted the lack of decisions to establish a definitive sentencing pattern.[111]

Queensland is a fertile source of appellate decisions dealing with young sex offenders. The sentencing range for rape extends from lengthy probation orders to significant periods of detention (up to five years).[112] The notorious case R v KU; Ex parte Attorney-General (Qld)[113] involved the rape of a 10 year old girl by nine offenders, of whom six were juveniles aged between 13 and 15 years, all of whom had significant criminal histories. Each was sentenced at first instance to 12 months’ probation without any conviction being recorded. The Attorney-General successfully appealed each of the sentences. Four of the juveniles were re-sentenced to three years’ probation with a conviction recorded, and the remaining two, who had made no real progress in rehabilitation and presented a significant risk of recidivism, were sentenced to three and two years’ detention respectively.

In contrast, R v MBQ[114] is a recent example of a case where a probation order withstood a Crown appeal. The young offender, a 12 year old boy, who suffered from foetal alcohol syndrome which reduced his intellectual functioning to that of a nine year old, pleaded guilty to penile/vaginal rape of a girl aged three. Penetration was minimal and the child was not physically injured. The boy had no offending history, a supportive foster family and promising rehabilitative prospects. Applying the relevant youth justice principles, three years’ supervision with a treatment condition and no recorded conviction was deemed an appropriate exercise of the judge’s discretion.

R v E; Ex parte Attorney-General (Qld)[115] exemplifies a case where a four year detention order was imposed by the Court of Appeal. The 16 year old young offender pleaded guilty to two counts of rape, four of attempted rape and one count of torture. The victim was a 30 year old woman who suffered from cerebral palsy and was wheelchair-bound. The offences were committed over a period of five days and the torture included kicking her, burning her with a cigarette, threatening to kill her with a knife and making small cuts on her hand and foot. The offender pleaded guilty after a contested committal; he had no prior criminal history and a background of neglect and abuse. A recent decision, R v IC,[116] is also a case where the victim was an adult. The 14 year old offender, who had no criminal history, followed and accosted a 24 year old woman in a public place, then carried her into some bushes and digitally penetrated her before she managed to escape. A sentence of 16 months’ detention was substituted for one of two years.

In Western Australia v A Child, the Court of Appeal noted that:

Sexual offences by a child against another child are relatively infrequent. There are only five cases in which this Court or the Court of Criminal Appeal has considered an appeal against sentence in those circumstances. ... In three of the five cases a non-custodial order was determined to be appropriate. In the two cases where a term of imprisonment was imposed the offender was aged 16.[117]

The offender in this case was 14 years old at the time of the crime and had significant cognitive limitations which further reduced his maturity. He was also himself the victim of child sexual abuse. However, the objective circumstances of the offending were serious. The complainant was a six year old boy and in the course of one episode he was anally penetrated by the offender twice, forced to perform fellatio on the offender once and threatened with death if he did not do what the offender said. The Court disagreed with the sentencing judge’s characterisation of the offending as ‘simply the manifestation of an adolescent sexual urge’[118] and suggested that there were real concerns about the offender’s maladjustment and the associated risk of him reoffending. Nevertheless, the Court rejected the State’s contention that the primary sentencing objectives in this case should be retribution, punishment and general deterrence and that a custodial sentence should be imposed. Given that the central issue was what was most likely to be the most effective course for eliminating or substantially reducing the risk of the offender committing further sexual assaults in the short, medium and long term, an intensive youth supervision order (a non-custodial order) was in the best interests of the offender and it was also in the broader public interest.

A recent review by the Court of Criminal Appeal in Director of Public Prosecutions v NOP[119] of sentences for rape of a child victim by a young offender has shown that the courts have consistently held that only a sentence of imprisonment or detention can fulfil the requirements of deterrence and denunciation in the case of rape. Sentences were found to range from six months’ detention to 4.5 years’ imprisonment. However, some sentences were partly suspended and one sentence of 18 months’ detention was wholly suspended.[120] In Director of Public Prosecutions v NOP, the Crown successfully appealed a sentence imposed under the provisions of the Youth Justice Act 1997 (Tas) for the rape and indecent assault of a girl of six, the niece of the 15 year old intellectually impaired young offender. It was held that the judge’s sentence, a probation order for two years, with a treatment condition and order adjourning the proceedings for 12 months on condition of good behaviour, combined with an order that no convictions be recorded, was manifestly inadequate. The appellate court held that it appropriately prioritised rehabilitation, but failed to give adequate consideration to the need for general deterrence and denunciation. The latter was explained in terms of the need to first, provide the victim with appropriate vindication and secondly, assuage informed public outrage at the rape of a child of six. The Court considered that a suspended detention order was the most lenient sentence that could be imposed. A suspended detention order of nine months and recorded convictions were substituted for the adjournment and non-conviction order.[121]

This article is an attempt to remedy the omission of juvenile sex offending from the Australian criminal justice literature on both sex offending and the juvenile justice system by examining the prevalence of juvenile sex offending and describing how the system deals with juvenile sex offences. To date, there has been no significant juvenile justice analysis of the Australian response to juvenile sex offending in the broader context of the juvenile justice system. Exploring the prevalence of juvenile sex offending has shown that a considerable proportion of sex offending appears to be perpetrated by juvenile offenders. Australian recorded crime data for 2012–13 show that juveniles are responsible for 18 per cent of recorded sex offences, that their rate of offending was higher than that of adults for these offences and that the peak age for these offences was 15. International studies using other sources suggest that the proportion of child sexual abuse committed by juveniles could be much higher. This picture is obscured by the hidden nature of sex offending in general, juvenile sex offending in particular, and profiles of sex offenders which are based upon victim surveys. It is further obscured by the fact that, compared with adult sex offenders, relatively few juvenile sex offenders appear before the courts, although they commit sex offences at a higher rate than adults and a similar proportion of their offending is sexual. For juvenile sex offending the attrition rate seems to exceed that for adult offenders, from recording to prosecution, and at the court stage, with more sex offence cases being dismissed in Children’s Courts and more non-adjudicated finalisations.

Interestingly, there appears to be resistance to formally allowing sex offences to be diverted from court using innovative approaches such as conferencing. Even if it is possible in theory, and in some jurisdictions it is not, it is rare for sex offences to be diverted to conferences and this is explained on the basis that such cases are regarded as ‘too sensitive’, ‘too risky’ and ‘too serious’ to be dealt with by a restorative process such as conferencing.[122] As so few cases reach court, and even if they do, many are not adjudicated, it would seem that informal processes of various kinds are at work.[123] If this is the case, and the criminal justice system is being by-passed, it raises questions about whether there are appropriate resources for dealing with these cases to be dealt with, including counselling and support for victims and rehabilitation programs for offenders. Further research is needed to complement Daly’s work, to follow what happens to juvenile sex offences through from reporting to finalisation.

We have seen that when juvenile sex offences are adjudicated and guilt is proven, custodial sentences are more common than for other offences. Despite this, the approach of the courts, as reflected in appellate decisions, is largely rehabilitative and reform-oriented. There were common themes in the appellate guidance. Even in serious cases of penetration of a victim under the age of 12, there appeared to be an emphasis on longer parole periods with treatment conditions being imposed;[124] wholly suspended sentences;[125] intensive youth supervision orders;[126] and probation orders.[127] A different approach has been taken when the victim was an adult or the juvenile offender is closer to adulthood – in such cases, deterrence and retribution are given more weight than rehabilitation.[128]

This paper does not seek to suggest how juvenile sex offences should be dealt with within the criminal justice framework – whether sexual offences should be amenable to cautioning, referrable to restorative conferences,[129] or whether serious sexual offences should be excluded from the Children’s Court jurisdiction. Instead, by reviewing the prevalence of such offending and describing the criminal justice framework, its aim is to stimulate debate on these issues. In particular, we suggest that neither reviews of the juvenile justice system nor reviews of sentencing of sex offenders should ignore juvenile sex offending. Contrary to societal perceptions, sexual offences by a child against another child are not an infrequent form of child sexual assault.[130] There is now a considerable body of forensic literature on juvenile sex offending, recidivism, specialisation and the effectiveness of specialised treatment. For example, there is little evidence to suggest that young people who commit sex offences are likely to become adult sex offenders, although they have comparatively high recidivism rates for non-sexual offences.[131] This research should help inform how the criminal justice system should respond to juvenile sex offending, including the placement of such offenders on sex offender registers. The emerging literature on different types of treatment is also relevant in this context,[132] although it has recently been noted in the context of intra-familial adolescent sex offenders that treatment programs tend to be based on programs developed for adult offenders and give inadequate focus to developmental issues and the influence of family.[133] In addition, further research is needed that charts the flow of juvenile justice cases from report to finalisation, so that the issue of attrition can be analysed in the context of an appropriate juvenile justice response.

This article’s concern with the lack of analysis of the way juvenile sex offending is dealt with by the criminal justice system should not be interpreted as a call for more forceful implementation of the criminal law, or for more cases to be formally processed, prosecuted and adjudicated by the courts. The danger of highlighting the significant proportion of sex offending perpetrated by youth is that juvenile sex offenders will be swept up in the current panic around sexual offending and also become the target of calls for increasingly harsher measures. This must be resisted. What is advocated here is an acknowledgment of the issue so that policies can be developed and adequate resources allocated to the assessment, referral, treatment and counselling services needed for a primarily rehabilitative and preventive approach, the approach which is echoed in appellate sentencing guidance.

[*] Professor Emerita, Faculty of Law, University of Tasmania.

[**] Associate Professor, School of Law and Justice, University of Canberra and Honorary Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Tasmania. Contact author: lorana.bartels@canberra.edu.au.

The authors are grateful to the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on an earlier version of this article.

[1] Julian V Roberts et al, Penal Populism and Public Opinion: Lessons from Five Countries (Oxford University Press, 2003) 131.

[2] Stacey Katz-Schiavone, Jill S Levenson and Alissa R Ackerman, ‘Myths and Facts about Sexual Violence: Public Perceptions and Implications for Prevention’ (2008) 15 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture 291, 292.

[3] The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse was established by the Australian Government in January 2013: see Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, About Us <http://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/about-us> .

[4] Cf Wendy O’Brien, Problem Sexual Behaviour in Children: A Review of the Literature (Australian Crime Commission, 2008). This report focuses predominantly on Indigenous young people, but acknowledges that ‘the demand experienced by the very limited number of programs on offer to children with problem sexual behaviour indicates that this behaviour occurs across the country, not only in Indigenous communities’: at 47; see also Wendy O’Brien, Australia’s Response to Sexualised or Sexually Abusive Behaviour in Children and Young People (Australian Crime Commission, 2010).

[5] In each Australian jurisdiction except Queensland, a ‘juvenile’ is defined as a person aged between 10 and 17 years of age inclusive. In Queensland, by contrast, a ‘juvenile’ is defined as a person aged 10–16 inclusive: see Kelly Richards, ‘What Makes Juvenile Offenders Different from Adult Offenders?’ (Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No 409, Australian Institute of Criminology, February 2011) 1. For the purposes of this article, ‘sexual offences’ are all offences which fall into the Australian Bureau of Statistics Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification for ‘Sexual assault and related offences’, which includes the production and dissemination of child exploitation material: Brian Pink, Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification – 2011 (Third Edition) (2 June 2011) Australian Bureau of Statistics, 32–5 <http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/

5CE97E870F7A29EDCA2578A200143125/$File/12340_2011.pdf>. We acknowledge, however, that there is a range of forms of sexual offending, some of which is of course much less problematic than others.

[6] This article does not attempt to address juvenile sex offender characteristics, nor to compare juvenile sex offenders with adult sex offenders or other juvenile offenders. For a recent summary, see David Finkelhor, Richard Ormrod and Mark Chaffin, Juveniles Who Commit Sexual Offenses against Minors (December 2009) Office of Juvenile and Delinquency Prevention, US Department of Justice <https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/227763.pdf>. Note, however, that their focus was on juveniles who sexually offend against other juveniles. Accordingly, this excludes the experiences of juveniles whose sexual assault victims are adults. See also Donna M Vandiver, ‘A Prospective Analysis of Juvenile Male Sex Offenders: Characteristics and Recidivism Rates as Adults’ (2006) 21 Journal of Interpersonal Violence 673; Paul Oxnam and Jim Vess, ‘A Typology of Adolescent Sex Offenders: Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory Profiles, Developmental Factors, and Offence Characteristics’ (2008) 19 Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology 228; Susan Dennison and Benoit Leclerc, ‘Developmental Factors in Adolescent Child Sexual Offenders: A Comparison of Nonrepeat and Repeat Sexual Offenders’ (2011) 38 Criminal Justice and Behavior 1089; Andrea Halse et al, ‘Intrafamilial Adolescent Sex Offenders’ Response to Psychological Treatment’ (2012) 19 Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 221; Wesley G Jennings, ‘Editorial’ (2012) 35 Journal of Crime and Justice 327.

[7] Brigitte Bouhours and Kathleen Daly, ‘Youth Sex Offenders in Court: An Analysis of Judicial Sentencing Remarks’ (2007) 9 Punishment and Society 371, 372, citing Franklin E Zimring, An American Travesty: Legal Responses to Adolescent Sexual Offending (University of Chicago Press, 2004) 112.

[8] Kathleen Daly et al, South Australia Juvenile Justice and Criminal Justice Technical Report No 3 – 3rd Edition – Sexual Assault Archival Study (July 2007) Griffith University <http://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/50287/kdaly_part2_paper4.pdf> .

[9] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4513.0 – Criminal Courts, Australia, 2012–2013 (27 March 2014) <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4513.0> , based on data in tables 12, 17, 22, 27, 32, 37, 42, 47.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Karen Gelb, Recidivism of Sex Offenders: Research Paper (Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council, 2007) 14.

[12] All sources of data about offending are likely to present only a partial picture of true offending patterns; for example, court data do not account for cases which are discontinued by the police. Conversely, victim surveys are unlikely to present an accurate picture in respect of rare offence types and generally do not report on offences involving child victims. For the limitations of different criminal justice data sources, see Don Weatherburn, ‘Uses and Abuses of Crime Statistics’ (Crime and Justice Bulletin No 153, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, November 2011); Chris Cunneen and Rob White, Juvenile Justice: Youth and Crime in Australia (Oxford University Press, 4th ed, 2011) 53–66.

[13] Kelly Richards, ‘Misperceptions about Child Sex Offenders’ (Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No 429, Australian Institute of Criminology, September 2011).

[14] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4906.0 – Personal Safety, Australia, 2012: Glossary (11 December 2013) <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4906.0Glossary12012> (emphasis added).

[15] Although it is acknowledged that information could be obtained from 18 year old respondents who had been victimised in the previous 12 months, this is unlikely to be an extensive source of data on this issue. It should be noted that the ABS ‘Recorded Crime – Victims’ dataset does not contain relevant information on this issue either, as it only disaggregates by age of victim, not age of offender: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4510.0 – Recorded Crime – Victims, Australia, 2013 (26 June 2014) <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4510.0> .

[16] See, eg, Richards, ‘Misperceptions about Child Sex Offenders’, above n 13.

[17] See Richards, ‘What Makes Juvenile Offenders Different from Adult Offenders?’, above n 5, 1.

[18] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4519.0 – Recorded Crime – Offenders, 2012–13 (24 March 2014), table 3 <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4519.0/> .

[19] Richards, ‘What Makes Juvenile Offenders Different from Adult Offenders?’, above n 5, 3.

[20] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4519.0 – Recorded Crime – Offenders, 2012–13, above n 18, table 6.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] For international research, see Finkelhor, Ormrod and Chaffin, above n 6, 6.

[24] Cunneen and White, above n 12, 56.

[25] Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council, Sentencing Children and Young People in Victoria (2012) 8.

[26] Richards, ‘What Makes Juvenile Offenders Different from Adult Offenders?’, above n 5, 3, 5.

[27] Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4519.0 – Recorded Crime – Offenders, 2012–13, above n 18, table 6.

[28] Ian Nisbet, Sacha Rombouts and Stephen Smallbone, Impact of Programs for Adolescents Who Sexually Offend: Literature Review (NSW Department of Community Services, 2005) iii, citing Jo Spangaro, Initial Presentations to Sexual Assault Services (NSW Health, 2001).

[29] Cameron Boyd and Leah Bromfield, ‘Young People Who Sexually Abuse: Key Issues’ (Practice Brief No 1, National Child Protection Clearinghouse, December 2006) 3, citing Linnea R Burk and Barry R Burkhart, ‘Disorganized Attachment as a Diathesis for Sexual Deviance: Developmental Experience and the Motivation for Sexual Offending’ (2003) 8 Aggression and Violent Behaviour 487.

[30] Russell Pratt and Robyn Miller, Adolescents with Sexually Abusive Behaviours and Their Families (Victorian Government Department of Human Services, 2012) 7. Others have suggested the prevalence is between 40 and 90 per cent: Wendy O’Brien, Australia’s Response to Sexualised or Sexually Abusive Behaviour in Children and Young People, above n 4, 5.

[31] Lorraine Radford et al 2011, Child Abuse and Neglect in the UK Today (National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, 2011) 88. Note the Crime Survey for England and Wales (formerly the British Crime Survey) only asks about victimisation in the last 12 months; it now includes victims aged 10–15 but provides no specific information about sex offences.

[32] For a recent review, see Kate Warner, ‘Setting the Boundaries of Child Sexual Assault: Consent and Mistake as to Age Defences’ (2013) 36 Melbourne University Law Review 1009.

[33] Cunneen and White, above n 12, 5.

[34] For discussion, see Gregor Urbas, ‘The Age of Criminal Responsibility’ (Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No 181, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2000).

[35] R v Groombridge [1837] EngR 314; (1836) 7 C&P 582.

[36] Matthew Waites, The Age of Consent: Young People, Sexuality and Citizenship (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005) 63, 68.

[37] See Warner, above n 32, for discussion.

[38] Kate Sutherland, ‘From Jailbird to Jailbait: Age of Consent Laws and the Construction of Teenage Sexualities’ (2003) 9 William and Mary Journal of Women and the Law 313. As Waites explains, the conceptual basis on which the current age of consent is founded is ‘deeply problematic’: Waites, above n 36, 211.

[39] See Urbas, above n 34; Richards, ‘What Makes Juvenile Offenders Different from Adult Offenders?’, above n 5.

[40] Neal Hazel, Youth Justice Board for England and Wales, Cross-national Comparison of Youth Justice (2008) UK Ministry of Justice, 30–1 <http://yjbpublications.justice.gov.uk/Resources/Downloads/

Cross_national_final.pdf>.

[41] See Criminal Code Act Compilation Act 1913 (WA) app B sch item 321(1); Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) s 45(1); Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) s 66C; Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) sch 1 items 210, 215; Criminal Code Act 1983 (NT) sch 1 item 127; Crimes Act 1900 (ACT) s 55(2). In South Australia and Tasmania, the age of consent is 17: see Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (SA) s 49; Criminal Code Act 1924 (Tas) sch 1 item 124. Note that the age of consent for sodomy in Queensland is 18: Criminal Code Act 1899 (Qld) sch 1 item 208.

[42] See Warner, above n 32, for a more detailed discussion.

[43] NSW, Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory do not have a similar age consent defence, while the other Australian jurisdictions (Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania and the ACT) do: see ibid 1015.

[44] J R Spencer, ‘The Sexual Offences Act 2003: (2) Child and Family Offences’ [2004] Criminal Law Review 347, 354.

[45] For a recent comment, see Tessa Akerman, ‘South Australian District Court Judge Paul Muscat Questions Why “Only Boys” Are Charged with Underage Sex’, Adelaide Advertiser (online), 29 May 2014 <http://www.adelaidenow.com.au/news/south-australia/south-australian-district-court-judge-paul-muscat-questions-why-only-boys-are-charged-with-underage-sex/story-fni6uo1m-1226934612872> .

[46] A notable exception is Victoria’s ‘dual track’ system, whereby a court can order that 18–20 year old offenders serve their custodial sentence in a youth justice centre instead of an adult prison if it determines the young person has reasonable prospects for rehabilitation, is particularly impressionable, immature or likely to be subjected to undesirable influences in an adult prison: Sentencing Act 1991 (Vic) s 32.

[47] Bouhours and Daly, above n 7, 373; Sumitra Vignaendra and Graham Hazlitt, The Nexus between Sentencing and Rehabilitation in the Children’s Court of NSW (Judicial Commission of NSW, 2005).

[48] For discussion, see Don Weatherburn, Andrew McGrath and Lorana Bartels, ‘Three Dogmas of Juvenile Justice’ [2012] UNSWLawJl 31; (2012) 35 University of New South Wales Law Journal 779. For a critique, see Kelly Richards and Murray Lee, ‘Beyond the “Three Dogmas of Juvenile Justice”: A Response to Weatherburn, McGrath and Bartels’ [2013] UNSWLawJl 32; (2013) 36 University of New South Wales Law Journal 839.

[49] Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council, Sentencing Children and Young People in Victoria, above n 25, 23. Note that the justice/welfare dichotomy has been widely criticised as sterile and inadequate to explain changes to the system of juvenile justice: see Cunneen and White, above n 12, 109–113 for an overview. For a recent discussion of some of the challenges associated with a restorative justice approach, including the potential for revictimisation, see Jacqueline Joudo Larsen, ‘Restorative Justice in the Australian Criminal Justice System’ (Research and Public Policy Series No 127, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2014).

[50] Weatherburn, McGrath and Bartels, above n 48.

[51] Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council, Sentencing Children and Young People in Victoria, above n 25, 29.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid 32.

[54] Daly et al, South Australia Juvenile Justice and Criminal Justice Technical Report No 3, above n 8, 47.

[55] See Weatherburn, McGrath and Bartels, above n 48.

[56] Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (Vic) s 414. Another diversionary program which police can recommend to the court is the Ropes Program; ‘Right Step’ and ‘GRIPP’ are other geographically restricted programs: for description see Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council, Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council, Sentencing Children and Young People in Victoria, above n 25, 33–5.

[57] Kelly Richards, ‘Police-Referred Restorative Justice for Juveniles in Australia’ (Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice No 398, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2010).

[58] See, eg, Young Offenders Act 1994 (WA) s 25, which states that a matter cannot be referred to a juvenile justice team if it is a prescribed offence. Prescribed offences include indecent assault: sch 2.

[59] See Richards, above n 57, 3–4, 7.

[60] Youth Justice Act 1997 (Tas) ss 9(1), 3 (definition of ‘offence’).

[61] Daly et al, South Australia Juvenile Justice and Criminal Justice Technical Report No 3, above n 8, 11.

[62] Ibid 64. See also Kathleen Daly, ‘Setting the Record Straight and a Call for Radical Change: A Reply to Annie Cossins on “Restorative Justice and Child Sex Offences”’ (2008) 48 British Journal of Criminology 557, 561.

[63] Daly et al, South Australia Juvenile Justice and Criminal Justice Technical Report No 3, above n 8, 64. See also Kathleen Daly, ‘Restorative Justice and Sexual Assault: An Archival Study of Court and Conference Cases’ (2006) 46 British Journal of Criminology 334, 352.

[64] Kathleen Daly et al, ‘Youth Sex Offending, Recidivism and Restorative Justice: Comparing Court and Conference Cases’ (2013) 46 Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 241.

[65] Annie Cossins, ‘Restorative Justice and Child Sex Offences: The Theory and the Practice’ (2008) 48 British Journal of Criminology 359.

[66] Juvenile Justice Act 1992 (Qld) sch 4 (definition of ‘child’).

[67] Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) s 61I: sexual intercourse without consent; aggravated sexual assault is sexual intercourse without consent in the aggravating circumstances listed in the section: s 61J.

[68] Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) s 61J.

[69] Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 (NSW) ss 28, 3 (definition of ‘serious children’s indictable offence’).

[70] Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (Vic) s 516.

[71] Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (Vic) s 356(3)(b). It is rare for the Children’s Court to decline to hear the matter and decisional law suggests that the Court should only relinquish its jurisdiction sparingly and with great reluctance: Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council, Sentencing Children and Young People in Victoria, above n 25, 43.

[72] Juvenile Justice Act 1992 (Qld) s 99, sch 4 (definition of ‘Supreme Court offence’); District Court of Queensland Act 1967 (Qld) s 61. See also Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) ss 215, 349.

[73] Young Offenders Act 1993 (SA) s 17.

[74] Bouhours and Daly, above n 7, 376.

[75] Children’s Court of Western Australia Act 1988 (WA) s 19.

[76] Youth Justice Act 1997 (Tas) s 161: jurisdiction of the Youth Justice Division of the Magistrates Court includes all indictable offences that are not prescribed offences (defined in s 3). The range of prescribed offences is more limited for offenders under the age of 14.

[77] Magistrates Court Act 1930 (ACT) s 288(1).

[78] Youth Justice Act (NT) s 52(1)(a).

[79] Australian Institute of Criminology, Juvenile Court System (11 November 2013) <http://www.aic.gov.au/

criminal_justice_system/courts/juvenile.html>.

[80] Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council, Sentencing Children and Young People in Victoria, above n 25, 42.

[81] Jennifer Temkin and Barbara Krahé, Sexual Assault and the Justice Gap: A Question of Attitude (Hart Publishing, 2008) 9; Kathleen Daly and Brigitte Bouhours, ‘Rape and Attrition in the Legal Process: A Comparative Analysis of Five Countries’ (2010) 39 Crime and Justice: A Review of Research 565, 568.

[82] Temkin and Krahé, ibid 18; Daly and Bouhours, ibid 568.

[83] Comparable data were not available in the 2012–13 dataset.

[84] Daly, ‘Setting the Record Straight and a Call for Radical Change’, above n 62, 559. See also Bouhours and Daly, above n 7, 389.

[85] Daly, ‘Setting the Record Straight and a Call for Radical Change’, above n 62, 559.

[86] Ibid 563.

[87] Louis Andrews, ‘No Conviction for Teen Sex’, Canberra Times (online), 5 September 2012 <http://www.canberratimes.com.au/act-news/no-conviction-for-teen-sex-20120905-25e8l.html#ixzz3CP7J6an0> . A Crown appeal against the sentence was rejected by the Court of Appeal: R v CV [2013] ACTCA 22; (2013) 233 A Crim R 67. The Court rejected the prosecution submission that the fact that the offender would become a registered child sex offender was irrelevant: at 79–81. See also Victorian Law Reform Commission, Sex Offenders Registration, Final Report (2012) 73–7; Sean Fewster, ‘SA Lawyers Call for Teens Involved in Genuine Relationships to Be Exempt from Sex Offenders Register’, The Advertiser (online), 25 May 2014 <http://www.adelaidenow.com.au/news/south-australia/sa-lawyers-call-for-teens-involved-in-genuine-relationships-to-be-exempt-from-sex-offenders-register/story-fni6uo1m-1226930936816> .

[88] Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (Vic) s 361; Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 (NSW) s 33(2).

[89] See, eg, Sentencing Act 1991 (Vic) s 5(1).

[90] Juvenile Justice Act 1992 (Qld) s 150(2)(c), sch 1 item 8; Young Offenders Act 1994 (WA) ss 6(d)(iii), 7(j), (m); Youth Justice Act 1997 (Tas) ss 5(1)(h), 5(2)(b), (d); Young Offenders Act 1993 (SA) ss 3(1), (3); Crimes (Sentencing) Act 2005 (ACT) s 133C(1).

[91] CNK v R [2011] VSCA 228; (2011) 32 VR 641, 652, 662. See also cases cited by Victorian Sentencing Advisory Council, Sentencing Children and Young People in Victoria, above n 25, 52; R v GDP (1991) 53 A Crim R 112, 114 (Mathews J); KT v The Queen [2008] NSWCCA 51; (2008) 182 A Crim R 571, 577–8 [22] (McClellan CJ at CL); JA (A Child) v Western Australia [2008] WASCA 70, [29]–[31]; DPP v NOP [2011] TASCCA 15, [41]–[42] (Evans J, Tennent and Wood JJ agreeing); R v Lovi [2012] QCA 24, [37]–[39]; Owens v Young [2013] NTSC 49, [31]; R v CV [2013] ACTCA 22; (2013) 233 A Crim R 67, 78 [40] (Higgins CJ, Burns and Katzmann JJ); R v P, A; P, A v Police [2013] SASCFC 3, [27] (Gray J).

[92] See, eg, Juvenile Justice Act 1992 (Qld) sch 1 item 8(a); Youth Justice Act 1997 (Tas) s 5(1)(a); Young Offenders Act 1993 (SA) s 3(2)(a); Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 (NSW) s 6(g); Youth Justice Act (NT) s 4(a).