University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

HARMING WOMEN WITH WORDS: THE FAILURE OF AUSTRALIAN LAW TO PROHIBIT GENDERED HATE SPEECH

TANYA D’SOUZA,[1]* LAURA GRIFFIN,[2]** NICOLE SHACKLETON[3]***

AND DANIELLE WALT[4]****

In Australia, gendered hate speech against women is so pervasive and insidious that it is a normalised feature of everyday public discourse. It is often aimed at silencing women, and hindering their ability to participate effectively in civil society. As governmental bodies have recognised, sexist and misogynist language perpetuates gender-based violence by contributing to strict gender norms and constructing women as legitimate objects of hostility. Thus, gendered hate speech, like other forms of hate speech, produces a range of harms which ripple out beyond the targeted individual. The harmful nature of vilification is recognised by the various Australian laws which prohibit or address other forms of hate speech. But as we map out in this article, gendered hate speech is glaringly absent from most of this legislation. We argue that by failing to address gendered hate speech, Australian law permits the marginalisation of women and girls, and actively exacerbates their vulnerability to exclusion and gender-based harm.

Since the shock victory of Donald Trump in the 2016 United States presidential election, western nations like Australia have witnessed a renewal of grassroots feminist activism, as movements such as #MeToo[5] and #TimesUp[6] continue to unfold across social media platforms and other public spaces. Accompanying such movements has been vehement backlash by conservative voices,[7] sometimes from unlikely quarters.[8] Gender roles and relations are not only the topic under debate – they also form the terrain upon which these discussions and struggles are playing out. The same can be said of language: the current shifts in cultural dynamics involve a contest over whose voices will be heard, and whose shut down. Hateful speech has become a key weapon in this struggle.

It is in this context that we focus on the issue of gendered hate speech (‘GHS’), canvassing possible definitions, as well as analysing its effects, its legal status, and its implications. Current approaches to defining and regulating hate speech in Australian laws indicate possible definitions of GHS. In particular, we examine how GHS could be defined broadly (progressively) or narrowly (conservatively), reflecting a focus on either the victim and their experience, or on broader public interests and security. Prohibiting GHS according to current laws on vilification would likely reflect a more conservative approach, and even prohibiting ‘offensive behaviour’ rather than vilification may still be interpreted according to concerns for the public interest.[9] This would be problematic in various ways, given that it does not address the harm to and perspective of the targeted individual, but would nonetheless represent a marked improvement over current absent or inconsistent laws.

We argue that GHS is best understood in its broader socio-political context, as a means by which patriarchal structures and norms are enforced through the policing of women’s presence and their behaviour. GHS also produces a range of troubling effects, not only on the individuals who are targeted, but on broader social groups and dynamics. As government bodies and scholars alike have confirmed, GHS can be seen as fuelling gender-based violence in Australia, through the perpetuation of gender prejudice and hostility.

Despite these harms, GHS is alarmingly under-regulated in Australia. An overview of Australian laws relating to vilification, offensive behaviour and the urging of violence on the basis of identity, exposes the glaring absence of any laws relating to hateful speech or speech inciting violence on the basis of gender in almost all Australian jurisdictions. In contrast, sex and gender (or gender identity) are recognised as important aspects of identity or categories of group membership deserving of protective measures in Australian laws relating to discrimination. But such anti-discrimination laws do not apply to individual verbal attacks.

By failing to legislate against GHS in any meaningful or systematic way, Australian law can be seen as complicit in the persistence of GHS, and by extension, gender-based violence. This is one of the key ways in which our legal system produces women’s vulnerability. We explain how a vulnerability analysis takes us beyond the standard arguments about the harms of hate crime. Crucially, it also helps to show why legislating against GHS would not simply be a protective, paternalistic form of state intervention, but one which can support women’s agency, especially their discursive and political agency in public spaces.

Before proceeding, two things are worth noting. The first is to acknowledge that there are other reasons to find statements that comprise GHS troubling. For instance, the speech may constitute family/intimate partner violence, verbal abuse and/or controlling and coercive behaviour. Likewise, conduct involving GHS may overlap with other areas of law, such as harassment or assault. Although we do not discuss these other areas of law or reasons for concern, we are conscious of them. But our focus in this article is specifically on the nature of GHS as hate speech and its place in Australian laws as such.

Second, we acknowledge the ways in which ‘proposals to regulate hate speech invariably end up citing such speech at length’, and that the recirculation of such speech ‘inevitably reproduces trauma as well’.[10] However, avoiding such repetition at all costs can also be counter-productive, as ‘[k]eeping such terms unsaid and unsayable can also work to lock them in place, preserving their power to injure’.[11] Troubled by the ways in which scholarly and other literature sometimes include instances of hate speech seemingly for shock value as much as for pedagogical or analytical purposes, we have chosen to repeat GHS sparingly rather than gratuitously in this article. We also warn readers that in some places where examples are provided, the content may cause offence.

In recent decades, hate crime has emerged as a ‘significant social, political and legal concern’.[12] It is difficult to conceptualise hate crime, or how it differs from other crime. One reason for this is that hate crime occurs ‘within a particular historical and cultural context’, and whether or not an ordinary crime is actually a hate crime can only be determined in light of that context.[13] Hate crime is not restricted to any particular type of criminal act. Almost any type of crime, including property, personal and sexual, which is committed with bias or prejudice as the underlying motive, can be classified as a hate crime. Criminal offences that have included hate speech, hate symbols, offenders with prior ties to organised hate groups, and even the timing of the incident (for example, coinciding with a holy day) may elevate an offence to hate crime status.[14] A distinction between graffiti and a hate crime may be as simple as the choice of image, such as a swastika. For crimes such as homicide, multiple offenders, excessive force, taunts, torture, and mutilation may distinguish hate crimes from parallel offences.[15] Critically, hate crimes can be distinguished from other forms of violence, which often include some form of relationship; hate crimes often involve the targeting of strangers.[16] When crimes involve known victims they tend to occur without motive beyond the person’s actual or perceived membership to a group.[17]

The term ‘hate crime’ has at times been used interchangeably with ‘bias crime’ or ‘prejudice-related crime’.[18] These terms also capture the idea that ‘hate crimes’ are not always motivated by hatred, but may instead be motivated by prejudice, contempt or intense dislike.[19] Definitions of hate crime vary, but tend to include the recognition of a targeted or minority group, the suggestion of prejudice or hatred as a motivator, and the notion of a victim as targeted on the basis of their actual or perceived membership in a group.[20] As a result, offences occur outside of other criminal motivators, such as substance abuse, jealousy, or money. Critically, the offender’s perception of the victim will inform whether an action is to be considered a hate crime. Their perception of the victim being a member of a targeted group need not be accurate, only present and considered a motivation for the offender.[21] As a category of criminal behaviour, hate crimes therefore exist in recognition of the complex motivations for hatred, as well as the profound impacts of hate crime on targeted groups, and wider society as a whole. In this way, hate crimes can be seen as a recognition of, and response to, vulnerability generated in an unequal society.

Hate speech is a particularly heinous form of hate crime as it threatens democratic ideals and causes direct harm to its targets as well as indirect harm to the community at large.[22] The purpose of hate speech is to ‘exclude its targets from participating in the broader deliberative processes required for democracy to happen, by rendering them unworthy of participation and limiting the likelihood of others recognising them as legitimate participants in speech’.[23] Hate speech clearly fits within the category of hate crime: hate speech is ‘prejudice enacted through speech’, and is used by the perpetrator to express hatred of, contempt for, or encourage violence against, an individual or a group of individuals on the basis of a particular feature or set of features.[24]

Hate speech also has similar effects as other forms of hate crimes. Hate speech is more than merely offensive; it directly and negatively impacts the individual target and causes harms in tangible ways.[25] Targets of hate speech feel fear, may be nervous to enter public spaces or participate in discourse, and may change their behaviour or appearance in an attempt to avoid hate speech.[26] Hate speech directly discriminates against its targets,[27] and encourages other members of society to view the targets as undesirable, and as legitimate objects of hostility.[28]

There is no settled legal definition of hate speech. Definitions vary depending on the country, jurisdiction (in a federal system such as Australia), and whether the law prohibiting hate speech is civil or criminal. Examples of hate speech definitions include: ‘speech or expression which is capable of instilling or inciting hatred of, or prejudice towards, a person or group of people on a specific ground’,[29] and ‘a public act inciting hatred, serious contempt or ridicule of a person based on a specific ground’.[30] This latter definition has been analysed by Weston-Scheuber, who notes that in different scenarios, ‘“public” and “private” are capable of different interpretations’.[31] In addition, legal definitions of hate speech often require that the speech be capable of ‘inciting’ violence, hatred or attack against the targeted group.[32] Accordingly, these definitions require that the act of hate speech be performed in public, and be so severe that it could incite other people to attack or ridicule the targeted group.

One reason for the focus on incitement in general hate speech definitions may be that the western understanding of freedom of speech is largely born of article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (‘ICCPR’), which states that limitations on freedom of expression are legitimate if they are necessary ‘[f]or the protection of national security or of public order’.[33] In addition, many hate speech laws in western states derive from the human rights basis for ‘sedition’.[34] Article 20(2) of the ICCPR states that ‘[a]ny advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law’.[35] The crime of sedition is enshrined in Australia in sections 80.2A and 80.2B in the Commonwealth Criminal Code.[36] In 2005, the Australian Government introduced amendments to section 80.2, framing the reform as necessary in order to protect both security and human rights; however, it is clear that the purpose of the legal change was to expand the scope of prohibition of the incitement of terrorism.[37] As in this example, in Australia, hate speech has been criminalised when it threatens public order or the security of the state. Any focus on vulnerability is arguably grounded in social control, rather than protection for marginalised groups.

Another reason why definitions of hate speech often require that the hate speech be capable of ‘inciting violence’ is to raise the threshold of harm required in order for the hate speech to be prohibited by law. Although debate continues, most academics agree that not all instances of hate speech should be prohibited by law; requiring that the hate speech be serious enough to be capable of inciting violence is one way to ensure that only the most severe cases of hate speech are caught by legislation.[38] This is particularly true if the hate speech is prohibited by criminal law, which requires a greater threshold of harm to be reached than civil law, as the penalty imposed on perpetrators often involves the loss of liberty.[39] However, this is not always the case; NSW has enacted civil laws prohibiting hate speech that ‘incite[s] hatred towards, serious contempt for, or severe ridicule of, a person or group of persons on the ground of the race of the person or members of the group’.[40]

The nature of hate speech as a hate crime, and therefore as a serious matter worth proscribing, is evidenced by the range of laws which address vilification and like practices throughout Australia. The next part provides an overview of such laws, with particular focus on whether they cover hate speech on the basis of gender.

This part will outline how GHS is (or is not) addressed within the Australian legislative framework by examining both hate speech laws and anti-discrimination laws at the federal and state/territory levels. We will begin our analysis by outlining the current statutory framework addressing hate speech within federal and state/territory jurisdictions. The wording used in these provisions is also discussed and specific focus is given to those provisions that include sex and/or gender as an attribute. We also briefly address the federal Criminal Code as it relates to the urging of violence against groups or members of groups with particular attributes. Moving on from the hate speech analysis, we will canvass anti-discrimination legislation within both federal and state/territory jurisdictions. Specifically, this analysis will include an examination of the ways in which protection is afforded in instances of discrimination on the basis of sex and/or gender.

As mentioned in the introduction, specific instances of GHS may breach other areas of law, such as harassment, assault, stalking or cyberbullying.[41] For example, in March 2018, the Commonwealth Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee reported on the Adequacy of Existing Offences in the Commonwealth Criminal Code and of State and Territory Laws to Capture Cyberbullying.[42] Numerous submissions and evidence presented to the Committee, outlined examples of cyberbullying and harassment against female journalists that would constitute GHS.[43] Existing criminal offences in the federal Criminal Code could be used to prosecute perpetrators of this type of behaviour.[44] GHS may also take the form of incitement to commit rape or sexual assault, which is prohibited in some jurisdictions.[45] However, although many instances of GHS would be prohibited by existing offences targeting specific kinds of conduct, gaps in the law remain.[46] There are many instances of GHS, as defined in the coming sections of this article, which would not be prohibited by current legislation. For example, GHS that is likely to ‘offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate’ may not constitute an offence under existing law (unlike racist hate speech, as prohibited by section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (‘RDA’)). Thus, existing laws which address particular forms of GHS can be said to be inadequate or under-inclusive. There is also symbolic importance to the legal recognition and prohibition of GHS per se. Simply reviewing existing piecemeal provisions which address particular forms of GHS would arguably misrecognise or overlook the phenomenon of GHS itself, and its harms as a form of hate speech against a particular demographic group.[47] Focusing on hate speech/vilification legislation and discrimination legislation thus allows us to analyse not simply how conduct constituting GHS is or is not addressed by existing laws, but the legal recognition of GHS itself.

This analysis reveals that GHS is glaringly absent from any legislative provisions addressing types of hate speech/vilification or urging of violence on the basis of identity in Australia. There are almost no legislative provisions that address gender as a ground for vilification or offensive behaviour, and the legislation that does address sex and/or gender as protected categories is varied in scope across jurisdictions. What is more, gender is an identity marker or category that is offered protection in anti-discrimination law, but such laws do not extend to hate speech by individuals. Based upon our examination of the legislative framework within Australia, we show that current hate speech and anti-discrimination legislation ultimately fails to prohibit or address GHS directly.

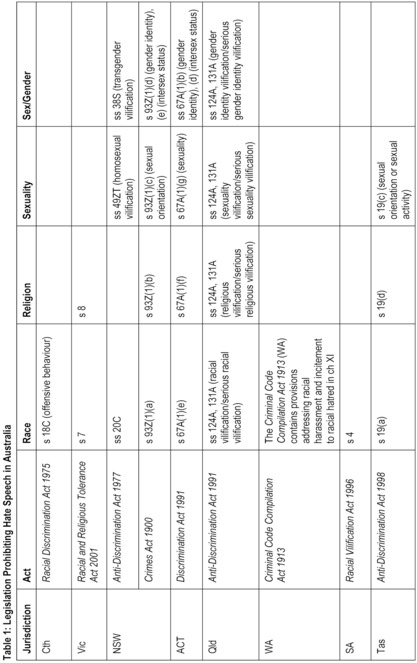

As summarised in Table 1 below, most jurisdictions in Australia have legislation prohibiting hate speech on the basis of various identities, including race, religion or sexuality.[48] Almost all of these legislative provisions address hate speech in the form of vilification (with the exception of Commonwealth legislation which instead refers to offensive behaviour). Generally, vilification is defined as conduct that incites hatred against, serious contempt for, or severe ridicule of a person or class of persons based on a particular attribute.[49]

At the federal level, legislation addressing hate speech is contained within section 18C of the RDA. Briefly, the provision prohibits offensive behaviour where it is likely to ‘offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate’ another based on their race, colour or national or ethnic origin.[50] In itself, section 18C has been the subject of relatively recent controversy, as some have criticised it as having unnecessarily expanded coverage of ‘trivial interests’,[51] and suggested that it should instead be confined to threats of physical violence or incitement of hatred.[52]

The well-known case of Eatock v Bolt considered section 18C and, in particular, the words ‘offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate’.[53] Briefly, the facts of the case concerned a series of newspaper articles and blog posts written by journalist Andrew Bolt, in which he described several prominent light-skinned Aboriginal people (the applicants) as ‘not genuinely Aboriginal and were pretending to be Aboriginal so they could access benefits only available to Aboriginal people’.[54] In his judgment, Bromberg J stated that section 18C was:

concerned with consequences it regards as more serious than mere personal hurt, harm or fear ... s 18C is concerned with mischief that extends to the public dimension. A mischief that is not merely injurious to the individual, but is injurious to the public interest and relevantly, the public’s interest in a socially cohesive society.[55]

Bromberg J recognised the relationship between harm to the victim and harm to the community and society in general, and even went further by adding that, in seeking to promote tolerance and protect against intolerance, the RDA should also include in its objective, tolerance for and acceptance of racial and ethnic diversity.[56] To this end, Bromberg J concluded that ‘the protection of reputation and the protection of people from offensive behaviour based on race are both conducive to the public good’.[57]

Although almost all states and territories have some form of hate speech legislation (see Table 1), hate speech directed at race, religion and sex and/or gender attributes are protected to varying extents. The Northern Territory also remains a notable exception, as it has not (yet) addressed vilification or offensive behaviour upon any attribute or ground.[58] Racial vilification is covered in all jurisdictions, with the exception of the Northern Territory. Hate speech directed at religion is only addressed in Victoria, ACT, Queensland and Tasmania. Vilification on the grounds of sexuality (homosexuality, sexual orientation or sexual activity) is addressed in NSW, ACT, Queensland and Tasmania.

With regards to gender, the scope of prohibition again becomes even more variable and piecemeal. For example, intersex status vilification is covered in ACT, and transgender vilification is explicitly addressed in NSW. But the basic category of gender – or more accurately ‘gender identity’ – is covered only in ACT, Queensland and Tasmania. While at first glance this appears to cover GHS, upon closer inspection we see that these provisions reflect a concern for transgender vilification. Thus in the Queensland legislation, ‘gender identity’ is defined by reference to a person who (a) identifies, or has identified, as a member of the opposite sex by living or seeking to live as a member of that sex; or (b) is of indeterminate sex and seeks to live as a member of a particular sex. The ACT and Tasmanian legislation share a more inclusive definition of ‘gender-identity’, as encompassing the gender-related identity, appearance or mannerisms or other gender-related characteristics of a person, with or without regard to the person’s designated sex at birth. This is the current extent of vilification legislation directly addressing gender-based hate speech in Australia.

The picture is similarly bleak when we consider federal criminal law. The Criminal Code prohibits urging violence (or the use of force) against a group on the basis of race, religion, nationality, national or ethnic origin or political opinion.[59] It likewise prohibits urging violence (or the use of force) against an individual on the basis of their (believed) membership of a group – again on the basis of race, religion, nationality, national or ethnic origin or political opinion.[60] Both of these provisions are limited in several ways, including requirements for an intention that the violence will occur, and that the use of force or violence would threaten the peace, order and good government of the Commonwealth. Once again, gender is conspicuously absent from the list of group identities protected under these provisions.

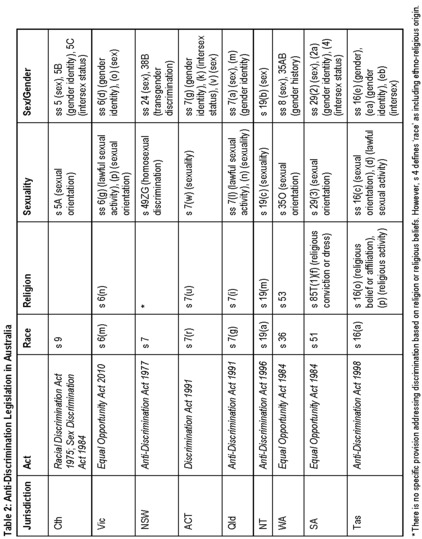

However, gender or sex is not an unknown aspect of identity or category of group membership in Australian law. All jurisdictions in Australia have enacted legislation addressing prejudice or persecution on the basis of sex or gender (among other grounds) in the form of anti-discrimination legislation. Although slight differences between the jurisdictions exist, generally discrimination is defined as unfavourable (or less favourable) treatment of a person on the basis of a particular protected attribute. Discrimination may be direct or indirect, and unfavourable treatment may take such forms as exclusion, restriction, or imposition of extra conditions or requirements.[61] Different attributes are covered in the various jurisdictions, as summarised in Table 2.

Jurisdictionally across Australia, all states/territories have enacted legislation prohibiting discriminatory conduct on the basis of race. Most jurisdictions also prohibit discriminatory conduct on the basis of religion, with the interesting exception of NSW: whilst it has no explicit provision prohibiting religious discrimination, the Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW) does define ‘race’ as including colour, nationality, descent and ethnic, ethno-religious or national origin.[62] Notably, a prohibition on discrimination directed at religion or religious belief is absent from federal legislation.

With regard to sexuality, discrimination based on sexual orientation is prohibited in Victoria, SA, Tasmania and WA; sexuality discrimination is prohibited in ACT, Queensland and NT; lawful sexual activity discrimination is addressed in Victoria, Tasmania and Queensland; and homosexual discrimination is addressed in NSW.

As with vilification legislation discussed above, discrimination on the basis of sex or gender is prohibited to varying degrees, with wide variation between the jurisdictions. Discrimination based upon intersex status is prohibited in the ACT, Tasmania and SA, while transgender discrimination is addressed in NSW, and gender history discrimination is addressed in WA. Gender discrimination is prohibited in Tasmania; however, the legislation does not define the term ‘gender’.[63] At the federal level, the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) addresses sex and/or gender by prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex, sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status. Definitions of ‘gender identity’ vary across jurisdictions; however, they all seek to protect transgender people, whether or not they have had medical intervention, and arguably, people who are gender non-binary, or gender non-conforming.[64] ‘Sex discrimination’ is defined broadly in the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth), which prohibits discrimination ‘by reason of: (a) the sex of the aggrieved person; (b) a characteristic that appertains generally to persons of the sex of the aggrieved person; or (c) a characteristic that is generally imputed to persons of the sex of the aggrieved person’.[65]

Despite offering important and wide-ranging protection to those who experience persecution or inequities on the basis of sex or gender, there are important limitations to discrimination legislation for the purposes of our analysis in this article. Such legislation, even where it defines sex or gender as a protected attribute, only prohibits unfavourable treatment in certain circumstances. These circumstances tend to address such potential discriminators as employers, partners in partnerships, qualifying bodies, educational authorities, providers of goods or services, and accommodation providers.[66] Simply put, discrimination legislation is aimed at the decision-making processes of institutional actors, and protecting individuals from unfair treatment by such actors. Thus, despite demonstrating legislators’ awareness of sex or gender (or gender identity) as attributes upon which individuals experience unjust treatment, discrimination laws fail to offer any protection against GHS per se.

This section has offered an outline of the areas of Australian law most relevant to hate speech on the basis of gender – namely, vilification laws (alongside federal legislation on offensive behaviour or urging of violence against protected groups) and anti-discrimination laws. Overall, this outline has illustrated a blatant absence of legislation directly targeting GHS. Many other attributes are offered protection under anti-vilification laws, and gender discrimination is prohibited in various jurisdictions. But there currently exists an undeniable gap in Australian law on the particular phenomenon of hate speech on the basis of gender. In the next Part we concentrate on this gap by analysing GHS and considering ways in which it could be defined through legislation.

So far, in this article, we have discussed hate crimes and hate speech generally, and we have analysed the current legislative framework for hate speech in Australia. It is clear that, currently, GHS is not consistently or adequately legislated on in Australia. Although largely unrecognised by law, GHS permeates all levels of social interactions and spaces from media personalities,[67] to educational institutions,[68] and social media outlets.[69] Many examples of GHS, some of which are discussed in the remainder of this article, show that whilst the degree of harm varies, GHS is so prevalent as to be customary and, in some circumstances, is even openly defended.[70]

In this section of the article, we will discuss two crucial issues. First, we discuss our choice of the term ‘gendered’ rather than ‘sexist’ or ‘misogynist’ hate speech, and whom we perceive to be the targets of GHS, namely women. Secondly, we discuss the different ways of defining GHS, particularly by outlining a conservative definition and a more progressive definition of GHS, considering the benefits and pitfalls of each.

By itself, gender refers to a socially constructed category that consists of a set of underlying assumptions, values and models about masculinity and femininity.[71] Gender norms concerning males and females are entrenched in public life and tend to be internalised and preserved within society,[72] while gender models revolve around traditional male and female conduct, roles and activities. Broadly stated, in traditional gender norms, pacifist, compassionate, nurturing and benign traits typify femininity whilst masculinity is portrayed as quintessentially warring, ruthless, competitive and aggressive.[73] Feminist scholarship has for almost two decades emphasised the nature of gender as socially constructed and performative.[74]

By using the term ‘gendered hate speech’ we seek to draw attention to the ways in which such speech is not simply focused on making claims regarding biological realities of sex differentiation.[75] For this reason, it is not simply ‘sexist’ hate speech. Rather, GHS can be understood as a practice by which gender is socially constructed on an ongoing basis, and where gendered norms and expectations are wielded in language-based attacks on individuals. Thus, GHS often takes the form of reprimands against an individual for behaviour which is perceived as a failure to conform to gender norms. Women are ‘more likely to be attacked when they [are] not performing gender appropriately’.[76] We do not explore further the question of deliberate behaviour which can attract or give rise to GHS (which is essentially akin to engaging in victim blaming, by locating the cause of GHS in a target’s conduct rather than a perpetrator’s).

The fact that lesbians are subjected to GHS, both because they are women and because they are lesbians, demonstrates the way in which GHS is used as a means to police gendered performance and behaviour.[77] Likewise, public comments by Eddie McGuire in 2016 about drowning sports journalist Caroline Wilson to raise money for charity were characterised as ‘a rebuke for being a strong, opinionated and tough woman’.[78] As being strong, opinionated and tough are widely perceived as ideally masculine traits, arguably Wilson was subjected to hate speech in an attempt to put her back in her place, as it were, and ensure that she performs her gender appropriately in the future.[79] A recent article by a journalist working for North American talk show The Agenda has discussed how women who appear on the show are subjected to death and rape threats for weeks, and sometimes months, afterwards.[80] These women were subjected to these forms of GHS not necessarily because of any controversial content of their contributions to the programme. Rather, they were targeted as women actively participating and voicing their opinions in a public arena – a space being defended, via GHS, as a territory belonging to men.[81] The same can be seen of GHS targeted at women occupying political offices in Australia – as then Prime Minister Julia Gillard famously decried in her ‘misogyny speech’.[82] In these examples, GHS is used to silence the individual target, and to (attempt to) prevent women from performing traditionally ‘masculine’ roles or traits, or occupying social roles and spaces which some believe should be reserved for men.

GHS is therefore not used against, or experienced by, men and women in the same ways.[83] Importantly, many of the ways in which language is used to police men’s performance of gender actively mirrors the categories and epithets used against women: a man who fails to perform his masculinity appropriately may be subjected to language which compares him with identities or traits deemed feminine, and therefore implicitly inferior.[84] Thus, much gendered verbal abuse against men still ultimately expresses misogyny and gendered hierarchies which deem femininity as lesser than or subordinate to masculinity.[85] The message, and harms, of such speech extend to women as well.

By adopting the term ‘gendered hate speech’, we recognise the theoretical possibility of GHS against other genders or groups, including men.[86] In particular, if the broader socio-political context were one of matriarchy (where feminine traits were systematically ranked and valued as higher than masculine ones), then GHS which is misandrist could exist in the same way that misogynist hate speech currently exists under patriarchy. But that is currently not the case in Australian society. In recognition that GHS takes the form of misogynist hate speech in our current social and political context, we have limited the scope of this article to the vulnerability of women to GHS, and some of the harms caused to women by this type of conduct.

Limiting our scope in this way is also consistent with categorisations of hate speech more generally. Parekh has written that, in order for conduct to be classified as hate speech, it must be ‘directed against a specified or easily identifiable individual or, more commonly, a group of individuals’.[87] As discussed above, we see women (and girls) as primarily the targets of GHS; they are also classified as an easily identifiable group. Here we are using the term ‘women’ or ‘woman’ in the broadest sense: because we attend to gender rather than sex, this includes any person who identifies as a woman, whether or not they were born biologically female.[88] It is also important to note that, as with all hate speech and hate crime, intersectionality is an important factor. Although all women are potential targets of GHS, not all women are equally likely to be subjected to GHS or affected by it in the same ways. Women of colour, Indigenous women, women who are not gender-conforming, women with a disability, lesbians or bisexual women, and transwomen experience a greater risk of being subjected to potentially more serious forms of GHS, such as rape or death threats.[89]

As discussed above, there is currently no settled definition of GHS, either in literature or legislation. One reason for this is the limited research on GHS.[90] The majority of work considering hate speech in Australia has focused on hate speech against racial, ethnic or religious minorities; for example, Gelber and McNamara have undertaken significant research examining the harms caused by racial vilification and the effectiveness of Australia’s racial vilification laws.[91] Other scholars, including Powell and Henry, have examined the way in which technology facilitates sexual violence and harassment, and the particularly gendered experiences of women subjected to online harassment, and the limits of the criminal law in preventing sexual violence online.[92] This is undoubtedly significant work in examining and critiquing Australia’s current anti-hate speech legislation, and for continuing the discussion of hate speech more broadly in Australia. However, this research does not specifically target the topic of GHS and its legal regulation in Australia.

Another reason why there is no settled definition of GHS is because all hate speech, whether it is racist, sexist, homophobic and/or transphobic, occurs on a spectrum, and what may be perceived as hate speech to one person or victim may not be to another.[93] In the late 1990s, Nielsen conducted field research in the United States examining the prevalence of racist and sexist hate speech in public.[94] Her research shows that there ‘is a wide spectrum of interactions that are considered problematic by targets’, and that sexist hate speech which occurs in public ranges from ‘compliments’, which women reported as ‘humiliating and insulting’, to ‘implied sexual threats’, sometimes accompanied by physical violence.[95] The fact that this type of hate speech occurs on a continuum of seriousness makes it difficult to develop a general definition of GHS. It is even more difficult to produce a legal definition of GHS, as there remains ongoing debate about how serious or severe GHS should be before it attracts the attention of the civil or criminal law, and whether the definition should focus on the harm caused to the victim or to the community.

It is not our intention in this article to propose a specific definition of GHS, as we are not arguing for any specific path of legislative reform. Instead, we will discuss some of the different possible definitions for GHS. The discussion builds on Part III above, which considered the legislative position of GHS in Australia. As can be seen from Tables 1 and 2, different definitions of hate speech (and of gender) currently exist in Australian laws. Some hate speech definitions focus on the harm caused to the victim (progressive), and others focus on the harm caused to public order (conservative). In this Part of the article, we will outline a conservative definition of GHS and a more progressive definition of GHS, and discuss the benefits and pitfalls of each.

1 A Conservative Definition of GHS

A conservative definition of GHS would simply replicate the general definitions of hate speech, as discussed above in the first part of the article, but replace the words ‘on a specific ground’ with ‘on the basis of their gender’. Weston-Scheuber has gone some way towards doing this, stating that ‘it seems that this definition would encompass at least gender-based epithets used against women in the presence of others that have the capacity to incite hatred, serious contempt, or ridicule on the basis of gender’.[96]

The definition of GHS put forward by Weston-Scheuber includes the same limitation as those definitions of hate speech discussed in Part III above, namely that the hate speech be capable of ‘inciting’ further hate by a third party. We argue that defining GHS in this way is conservative, as it suggests that hate speech laws are more concerned with protecting ‘public order’ than preventing harm to victims. This definition prohibits GHS on the basis that it may lead to further criminal acts, rather than prohibiting GHS because it causes direct harm to the victim.

The conservative definition of GHS is problematic. It shifts the focus of the harm caused by hate speech from the victim or victims, to disruption caused to the ‘public order’ of the state. By defining GHS in this way, the direct and serious harm that language can cause is ignored, and the prevalence of GHS in day-to-day interactions is ignored.[97] One of the possible reasons for the lack of legislative attention on the direct harms caused by hate speech in general, and GHS in particular, is that those not routinely subjected to hate speech are often unaware of the serious harm it can cause. Nielsen’s study demonstrated that men ‘are often not aware of the extent to which women are the targets of offensive or sexually suggestive remarks’,[98] or that even subtle forms of sexist hate speech cause fear in those targeted.[99] By defining GHS according to the speaker’s intentions, or the capability of the speech to incite further ridicule, certain forms of GHS that ‘affect the day-to-day lives of women are excluded from the definition’.[100]

2 A Progressive Definition of GHS

While the conservative definition of hate speech, which usually includes the requirement that the hate speech be capable of inciting further action, is relatively settled in literature and legislation, the progressive definition of hate speech is not. A progressive definition of GHS would focus on the direct harm caused to the victim, rather than focusing on the harm caused to the community and public safety. An example of a progressive hate speech definition can be found in the RDA. Section 18C(1) states:

(1) It is unlawful for a person to do an act, otherwise than in private, if:

(a) the act is reasonably likely, in all the circumstances, to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or a group of people; and

(b) the act is done because of the race, colour or national or ethnic origin of the other person or of some or all of the people in the group.

The RDA defines ‘otherwise than in private’ to mean ‘words, sounds, images or writing’ which are to be communicated to the public,[101] or an act ‘done in a public place’,[102] or an act that ‘is done in the sight or hearing of people who are in a public place’.[103] Public place includes ‘any place to which the public have access as of right or by invitation, whether express or implied, and whether or not a charge is made for admission to the place’.[104]

This definition maintains the requirement that the hate speech occur in public; however, there is no requirement that the GHS incite further action by another person. The requirement for public utterance is an admittedly significant limitation of the progressive definition, which means that it is still not truly victim-centred. Limiting a definition of GHS to speech which takes place in public is problematic because it excludes much of the hateful speech that women are subjected to as women. In adopting a focus on public speech, we are following the legal standard for offensive behaviour, as just explained. We would also advocate a very broad interpretation of ‘public’ to include all open or group online spaces (including social media and even gaming platforms), media such as television/radio/print media, and ideally all physical spaces beyond private residences. The ‘public’ nature of GHS impacts upon the kinds of harm that it creates – not only to the individual target, but because such speech is capable of influencing the behaviour and beliefs of other members of the public, whether they are members of the targeted group or not.

At first glance, it would appear easy to replicate section 18C of the RDA to create a progressive GHS definition with the words ‘race, colour or national or ethnic origin’ replaced with ‘gender’. The threshold of harm in this progressive definition of GHS, that is, that the ‘act is reasonably likely ... to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate another person or a group of people’, is not concerned with the likely effect on the community or a wider audience.[105] Rather, this definition focuses on the ‘negative effects of the conduct on members of the targeted group’ by addressing direct harms caused by GHS.[106] However, as discussed in Part III above, the scope of section 18C was narrowed in Eatock v Bolt in 2011, when Bromberg J limited section 18C to ‘mischief that extends to the public dimension’.[107] In order for conduct to fall within section 18C, then, the speech must be ‘more serious than mere personal hurt’, and must be ‘not merely injurious to the individual, but ... injurious to the public interest and relevantly, the public’s interest in a socially cohesive society’.[108] Interpreted in this way, section 18C becomes more similar to the conservative definition, in that it is less concerned with the effect caused to the victim, and more concerned with how the speech impacts on the public.

However, it would be possible to define GHS in a way that goes beyond the limits imposed by Eatock v Bolt. While there is currently no legislation in Australia which could be used to model a progressive definition of GHS in this way, we argue that this does not mean that it would not be possible in the future to formulate a legislative definition of GHS that better captures progressive ideals. This type of GHS definition would be progressive as it challenges the argument that the harm suffered by individuals subjected to GHS is less serious, and therefore less deserving of protection, than the risk that the GHS might influence the behaviours and beliefs of others.[109] The focus on the direct harms caused to victims in a progressive definition would better acknowledge the targeted individuals’ experiences of GHS.[110] This type of GHS definition would potentially cover a wider variety of acts; for instance such a definition would encompass much of the day-to-day sexual harassment that women are routinely subjected to as soon as they enter public space.[111]

In this Part we have analysed conservative and progressive forms of GHS definitions, and discussed the different focus of each. Before considering whether it is appropriate to legislate against GHS – on the basis of either of these definitions – it is necessary to consider the impacts and harms that such speech causes. This is the task of the following Part V.

In this Part of the article, we will examine some of the negative effects caused by hate speech in general, and GHS in particular.

Hate speech impacts its targets in a similar fashion to other forms of hate crime. Hate crime is understood to have impacts extending beyond its individual target, and into communities and societies as a whole. This view is neatly captured by Iganski, who identifies five levels of harm resulting from hate crime, with ripple effects spreading out from initial victims, to immediate and broader symbolic groups, to other excluded communities, and finally to societal norms and values.[112] Those on the receiving end of hate crime are therefore affected on multiple levels; they are impacted by the initial incident, as well as the subsequent impacts on identity and community.

Targets of hate crime experience a number of tangible, negative effects. Compared to victims of parallel crimes, hate crime victims are more likely to experience depression, anxiety and nervousness, problems with sleep, feelings of fear and loss of confidence.[113] For the wider community, such crimes have a ‘terrorizing effect’.[114] This is because hate crimes indicate underlying social and cultural tensions, and endemic bigotry.[115] Hate crimes therefore have the ability to silence marginalised voices further, causing them to withdraw from public discussion, and damage ‘multiculturalism, equality and harmony’.[116]

The harms caused by hate speech are not limited to their impact on the individual to participate and influence political policy but extend through to broader impacts on society. In particular, it is possible to classify the harms of hate speech as either constitutive harm (occasioned in the saying of the hate speech) or consequential harm (occurring as a result of the hate speech).[117] Constitutive harms are harms caused directly to the individual targeted by the hate speech. These types of harms include psychological distress, silencing and impact on self-esteem, as well as wider considerations such as restrictions on freedom of movement and association.[118] Consequential harms are harms caused by indirect effects on individuals who were not the target of the hate speech, and who usually form part of wider society.[119] These types of harms may include persuading those hearing the speech of negative stereotypes, leading to further harmful conduct.[120]

This model – of direct, or ‘constitutive’ harm, and indirect, or ‘consequential’ harm of hate speech[121] – can also be applied to understand the impacts of GHS.

1 Direct or ‘Constitutive’ Harms of GHS

The direct, personal impacts of GHS are well documented. GHS can cause trauma, such as fear, sleeplessness, paranoia, feelings of threat and lack of safety, and ostracism or social exclusion.[122] Nielsen’s study illustrated that all forms of GHS can have serious impacts on the targets of such speech. Women reported feeling intimidated, afraid and threatened because of GHS directed at them by strangers in public places.[123] The fear women felt after being the target of GHS led to silence – 42 per cent of women stated that they ignored the GHS because of fear.[124] The silencing effect of GHS can be seen in all kinds of public spaces. Recall the example cited above regarding women, often university professors and experts in their respective fields, who refused to (re)appear on a television program due to the hate mail they received after previously being hosted.[125] The hate mail they received often took the form of GHS, in particular, the women often received rape threats. One woman stated that she ‘found [herself] quite effectively silenced’ by her experience of GHS.[126] In Australia, the resignation of Rosie Batty from her public activism via the Luke Batty Foundation likewise demonstrates the profound silencing effect of GHS.[127] Rosie stepped down, in part, because of the unrelenting hatred and trolling she was subjected to by critics, including a number of media commentators.[128] These examples highlight that the direct effects of GHS on the individual targets are neither trivial nor inconsequential. GHS has lasting impacts on women, in terms of both their mental health and ability to participate in society free from fear.

2 Indirect or ‘Consequential’ Harms of GHS: Fuelling Gender-Based Violence

One of the most concerning indirect impacts of GHS is its role in perpetuating violence against women, or gender-based violence (‘GBV’). GBV is a term used to refer to violence that affects women disproportionately or that is specifically directed at women because of their gender.[129] GBV characterises any violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering, including coercion and arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life.[130] ‘Gender-based’ is attached to ‘violence’ so as to reflect the way that such violence is shaped by gender roles and hierarchies within society.[131]

It is difficult to overstate the prevalence of GBV in Australia. In recent years, the profound impact of GBV has occupied national news headlines[132] as well as appearing on the political agenda.[133] What is significant about the multitude of government and non-government reports on the issue of GBV, is that they recognise that the majority of GBV is committed by men against women in private settings.[134] For example, statistics[135] show that between 2010 and 2012, 76 per cent of reported intimate partner homicide victims were female.[136] Men killing their female (current or former) partners accounted for almost 80 per cent of all intimate partner homicides in Australia between 1 July 2010 and 30 June 2014.[137] Likewise, in Victoria, female victims of family violence made up 75 per cent of family violence incidents attended by police from 2009 to 2015.[138]

GBV can be considered a consequential harm of GHS, as language reflects and informs social norms and attitudes. The attitudes and beliefs that inform misogynist language are closely connected with men’s violence toward women.[139] The literature establishing this link has been summarised in a report commissioned by VicHealth,[140] which states that ‘[m]en who hold traditional views about gender roles and relationships, have a strong belief in male dominance or who have sexually hostile attitudes are more likely to perpetrate violence against their [female] intimate partners than those who do not’.[141] More broadly, ‘[p]eople who hold traditional views about gender roles or who have lower levels of support for gender equality are more likely to accept violence against women than those who hold more egalitarian beliefs’.[142] These relationships, attitudes and beliefs were discussed in the Victorian State Government survey ‘Community Attitudes Toward Violence against Women’[143] in considering the causality of harm between GHS and GBV.

Similarly, reports issued by the Australian Human Rights Commission,[144] Our Watch Australia,[145] White Ribbon Australia,[146] Commonwealth Department of Social Services[147] and the Royal Commission into Family Violence[148] assert that gendered beliefs and language are definitively linked to GBV.[149] The fact that so many federal and state government organisations, and reports from investigations commissioned by government, have explicitly identified the link between GHS and the prevalence of GBV is noteworthy, particularly in light of the fact that most jurisdictions continue to ignore the possibility of a prohibition on GHS (as summarised in Part III above).

The concept of ‘rape culture’ also helps us to trace the connections between GHS and GBV. This is because violence-supportive attitudes are inscribed within wider social norms relating to gender and sexuality. The concept of ‘rape culture’ explains how female objectification is routinised by encouraging boys and men to carry out normalised male sexual aggression.[150] A term coined by feminist scholars in the 1970s, rape culture refers to societal attitudes that tolerate and normalise rape and sexual violence through the encouragement of male aggression/dominance and female passiveness/submissiveness.[151] The scope of rape culture is large, encompassing social, cultural and structural discourses and practices that tolerate, accept, eroticise, minimise and trivialise sexual violence.[152]

It is important to differentiate between rape culture and the explicit promotion of rape.[153] It is clear that not all social institutions or dominant discourses encourage or legitimise GBV, not least because there are laws and policies that specifically prohibit such conduct.[154] But the concept of rape culture is subtler than this, because it persists within our language, media, social norms and culture. When viewed through this lens, prevalent social attitudes and beliefs about rape reflect, inform and influence our language, social norms and culture.

As briefly discussed in Part IV, the concept of misogyny is also helpful to understand the nature and impacts of GHS. However, given different uses of this terminology, some clarification is in order. As Manne has convincingly argued, misogyny is commonly understood as an individualised, pathologised phenomenon – the attitude or act(s) of a lone person who harbours an unusual hatred and acts upon it in exceptional ways (notably, this is something akin to taking the perpetrator’s perspective, in terms of focusing upon their motivations or intentions). In contrast, Manne advocates a more expansive approach to defining misogyny:

I argue that we should think of misogyny as serving to uphold patriarchal order, understood as one strand among various similar systems of domination (including racisms, xenophobia, classism, ageism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, and so on). Misogyny does this by visiting hostile or adverse social consequences on a certain (more or less circumscribed) class of girls or women to enforce and police social norms that are gendered either in theory (ie, content) or in practice (ie, norm enforcement mechanisms).

... we should ... understand misogyny as primarily a property of social environments in which women are liable to encounter hostility due to the enforcement and policing of patriarchal norms and expectations ...[155]

GHS can thus be understood as one of the forms this hostility often takes – one of the tools of misogynist gender-policing. This approach better corresponds to the realities of GHS seen from the targeted woman’s perspective. For instance, Nielsen’s research demonstrates the variety of ways in which GHS reported by women who participated in her study made them ‘uncomfortable and afraid to be in public’ and was ‘an effective mechanism for reinforcing the dominant position of men over women in public’.[156]

The individualised versus structural approaches to understanding misogyny can also be applied to expand our understanding of GBV and its place in Australian law. Currently, the Australian legal system addresses GBV through the use of laws that focus upon the individualised nature of each offence[157] and attempt to punish each offender and protect the victim accordingly. Scholars have pointed out that this method is flawed because it only identifies individual risk factors associated with the offence and ignores pervasive precursors such as societal norms and structures that underpin the offence.[158] As we have analysed in this article, and as recognised by government bodies, stereotypical assumptions about gender identities and roles increase the tendency for GBV in a number of ways. Reports claim that male-dominated power relations in relationships and families[159] are among the most consistent predictors of GBV because of the prevalence of traditional and conservative views about gender roles, relationships and beliefs that support male dominance and reflect sexual hostility toward women.[160] Furthermore, reports show that a proclivity for GBV is present among men who exhibit hostility toward female non-conformance to gender roles and challenges to male authority.[161]

Language is one powerful way in which these norms and stereotypes about gender are perpetuated, and GHS is an important mechanism by which misogynist hostility and policing takes place. Adopting this broader structural understanding of GHS accords with theories of hate crime which likewise seek to locate such crimes within larger systems of power and domination. As Perry states, hate crime

is a mechanism of power and oppression, intended to reaffirm the precarious hierarchies that characterize a given social order. It attempts to re-create simultaneously the threatened (real or imagined) hegemony of the perpetrator’s group and the ‘appropriate’ subordinate identity of the victim’s group.[162]

While these comments relate to hate crime generally, they can be applied fruitfully to understand hate speech in particular. We therefore argue that GHS is best understood as a mechanism for reinforcing power imbalances and social hierarchies,[163] and specifically as an instrument of misogynist hostility serving to uphold patriarchal structures.

Such a structural view helps us to understand where GHS comes from, and not just trace its impacts. That is, rather than starting with an instance of GHS as a cause and tracing its harmful impacts outwards from the individual target, if we see GHS as operating in a socio-political context of patriarchy and rape culture, then we can see how these broader structures both give rise to GHS and are reinforced by it. How do we hold on to this structural understanding of GHS, while still appreciating women’s ongoing agency and capacity for action within these structures? And what are the implications for understanding the role of legislation? This is the topic of the next part.

Let us summarise the broad arguments advanced thus far. Part II considered the general nature of hate speech as a hate crime, leading to a review of Australian laws in Part III which revealed the absence of any legal prohibition of GHS in most Australian jurisdictions. This is despite vilification provisions addressing various other aspects of identity, and despite gender being a protected identity characteristic under discrimination laws. Part IV then considered different definitions of GHS – focusing either on the potential for incitement, or on the experience of the person targeted by hate speech. Part V then went on to outline the kinds of harm produced by hate speech generally, and by GHS in particular. GHS was shown to have a range of harmful impacts – not only on the woman targeted, but for all women, through the perpetuation of gender-related norms and attitudes which fuel GBV. Despite these connections being acknowledged in government reports and campaigns, government actors have generally been deafeningly silent as to the possibility of law reform to interrupt such harmful speech.

The most obvious inference from these arguments is that by failing to prohibit GHS, our legal system is complicit in producing the ongoing harms of such speech as endured by women in Australia. But does this necessarily mean that state action – in the form of legislation against GHS – is the best or even an appropriate response? In this Part we consider and respond to various reasons against such a measure.

One powerful argument against legal measures to prohibit or restrict GHS is that such laws would necessarily contribute to norms and attitudes which cast women as passive, weak and in need of protection. In this section we work through these concerns by drawing on the concept of vulnerability, and, in particular, recent feminist scholarship which explores the connections between vulnerability and agency or resistance.

Vulnerability is a fraught concept for critical and feminist scholars for various reasons. First, using the language of vulnerability to speak or write about women’s experiences of oppression risks interpretations which take vulnerability ‘as a primary existential condition, ontological and constitutive’.[164] We are thus at pains to stress that we do not engage with vulnerability as an essential identity for women (or anyone else): women are not inherently, naturally, or inevitably vulnerable, beyond the ways in which all human life can be understood as vulnerable or precarious.[165] However, it would also be false to say that all humans are equally vulnerable, in the sense of being susceptible to harm or suffering. Rather, vulnerability is differentially distributed across the social landscape: some are more vulnerable than others. These disparities in vulnerability are produced – socially, discursively and legally. As well as being a condition which is inherent to the embodied experience of living, then, vulnerability is also a state or circumstance that is constructed (socially, discursively and legally) and therefore changeable.[166]

Secondly, we acknowledge that the term vulnerability is easily appropriated for a range of political interests or ends. For instance, xenophobia and nationalism are often articulated by reference to the ‘vulnerable’ nation, whose purity or safety is threatened by immigrants, terrorism and other threats discursively constructed as foreign.[167] A conceptual frame of vulnerability does not necessarily tend to a more liberal or conservative political agenda. This suggests a need to attend carefully to the ways in which it is used: who or what is claimed to be vulnerable, and in what precise ways?

Thirdly, we are conscious of the larger narrative pattern into which we can so easily fall when analysing gendered harm and violence, and especially when employing the language of vulnerability:

Our culture, politics, and academic criticism remain troublingly invested in a story of female fragility, a story based on a few key assumptions: women, children and non-masculine men are the victims of male violence, female injury demands society’s retribution, and pain renders the victim of violence helpless.[168]

Significantly for our purposes, this kind of vulnerability narrative often involves calls, whether implicitly or explicitly, for paternalistic intervention: for rescue, for protection. By considering the vulnerability of women, and in our case especially by considering the legislative inaction of a would-be protector state, we run the risk of portraying women as weak, dependent, and in need of protection.

However, as Butler explores, such ‘concerns [about using the language of vulnerability] assume that vulnerability is disjointed from resistance, mobilization, and other forms of deliberate and agentic politics’.[169] The ‘discourse of vulnerability’ need not ‘discount the political agency of the subjugated’,[170] if in interrogating vulnerability itself we can see its potential to coexist with a capacity for agency. This is precisely the task recently taken up by critical feminist scholars, and led by Butler.[171] Appreciating or imagining the vulnerable yet active political agent requires us to view vulnerability as never finally or completely paralysing. Moreover, individuals do not simply act to minimise their vulnerability or avoid any prospect of harm. The very opposite may be true, as Butler acknowledges ‘I want to argue against the notion that vulnerability is the opposite of resistance. Indeed, I want to argue affirmatively that vulnerability, understood as a deliberate exposure to power, is part of the very meaning of political resistance as an embodied enactment’.[172]

A vulnerability frame therefore helps us to see GHS in its structural context and the full extent of its effects, while not denying the ongoing agency of women. The example that is made of a woman daring to appear or speak publicly, and thus expose herself to potential GHS, demonstrates and produces the vulnerability of any woman to be so targeted. But this does not preclude women acting and speaking in public spaces, whether tangible or online. The concept of vulnerability allows us to appreciate the ways in which women are impacted by such language, even as they continue to act and to speak.[173]

Just as ‘the freedom to gather as a people is always haunted by the imprisonment of those who exercised that freedom and were taken to prison’,[174] a woman’s freedom to appear publicly or speak in a public forum is laden with her awareness of women who have done so before and then been attacked – verbally or otherwise. This sense of risk or susceptibility is inexorably shaped by an individual’s location in space and time, some locations being experienced as riskier than others. But the mere fact of a woman’s presence in public space is enough to invite gendered slurs: the examples of GHS that women were subjected to in Nielsen’s study demonstrate that ‘for women, simply venturing into public places carries with it the risk of being the target of sexist speech’.[175] A woman’s vulnerability is therefore not escapable simply by modifying her own conduct or appearance.

Of course, vulnerability is also produced along other lines of difference, not just gender. Race, class, ethnicity, religion, disability, sexuality, age, trans identity, etc, are all attributes which shape a woman’s vulnerability and exposure to harm. Thus, while arguing that GHS contributes to the production of vulnerability for all women, we are not claiming that all women experience an equal level or kind of vulnerability.

Examples illustrating intersectionality of GHS with other forms of hate speech include the abuse directed at Linda Thorpe after her election as the first Aboriginal women to the Victorian Parliament in 2017, Tarneen Onus-Williams after a speech on 26 January 2018, and Alice Springs Councillor Jacinta Price. All three women are Aboriginal and outspoken about issues important to them. Thorpe states that she was ‘accustomed to being attacked for voicing her opinion’ as a strong Indigenous woman who has grown up dedicating her life to the Aboriginal cause. However, once she entered Parliament, the hate speech directed at her took on a gendered nature, as she received ‘quite detailed gang rape threats’.[176] Onus-Williams also received rape threats[177] and was body shamed by The Daily Telegraph.[178] Price also received rape threats in response to her support of Australia Day remaining on January 26.[179] Likewise, Muslim Australian Yassmin Abdel-Magied was subjected to death threats, as well as being sent videos of beheadings and rapes, in the controversy following her ANZAC Day-related tweet in 2017.[180]

In these cases, it was not merely the content of their political comments which led to these women being attacked through hate speech. Rather, it was that they had, as women – and as Indigenous or Muslim women – dared to occupy such public spaces and roles as vocal representatives of their communities, which triggered a GHS response. Appreciating intersectionality means acknowledging that the specific ways in which gendered norms and attitudes may be mobilised through GHS reflect (and reproduce) the target’s identity – as Indigenous, or disabled, or lesbian, for instance. Not all women are equally vulnerable to GHS, or vulnerable to the same kinds of GHS. And yet, any instance of GHS reproduces all women’s vulnerability to misogyny by reinscribing the complex category of ‘woman’ as a (purported) legitimate target of contempt, hateful speech, and even violence.

A vulnerability analysis therefore builds upon the earlier parts of this article which placed GHS in a structural context. This enables us to see that state inaction, in the form of failing to legislate, works to produce women’s vulnerability to GHS in public spaces. This has a silencing effect which, though never complete, is worth attending to and worth challenging. What is more, building upon feminist conceptualisations of vulnerability enables us to move beyond any argument that is simply an essentialist account of women’s vulnerability or weakness as a justification for calling upon state action in the form of paternalistic protection. Rather, legislation against GHS could be seen as an important tool for interrupting the social and discursive production of women’s vulnerability, to better facilitate women’s own agency and capacity for engagement in public life and debate. Adopting recent critical feminist conceptions of vulnerability – as not precluding agency – allows us to overcome this concern or dilemma. Keeping this framing in mind, we now move to consider other arguments which have been put forward against legislating on GHS.

There are also other potential arguments against legislating for GHS. In this section we will not engage with arguments against addressing hate crimes more generally: our starting point is that hate crimes are worthy of separate legislative recognition (as demonstrated by current Australian law summarised above).[181] However, there is ongoing academic and legal debate about whether ‘gender’ should classify as a category in laws prohibiting hate crime, including hate speech.[182] This debate centres on legislation which takes a ‘silo’ approach to prohibiting hate crime – where a general prohibition against hate crime or hate speech is accompanied by a list of characteristics, such as race, religion, and sexuality.[183] As we saw in Part III, gender is noticeably absent from almost all of these provisions. One justification put forward for this absence, is that women are not a ‘minority’ and therefore do not require the protection afforded by hate crime laws.[184] However, as we have seen in Part V, GHS is best understood within a context of norms and practices relating to gender roles and relations: as a form of hate speech it is undoubtedly tied to power hierarchies and can be seen as a practice of structural misogyny and subordination. Also, as we saw in Part III, sex and gender are recognised by anti-discrimination law as aspects of identity deserving of protection against adverse treatment – alongside race, religion, and sexuality.

It is also argued that gender should be excluded from hate crime and hate speech laws because gender is ‘a complicated identity character’, and including gender as a characteristic would ‘essentialise gender and ignore the intersection of race, class, religion and sexual orientation’.[185] This is because the categories of hate speech, such as race, religion and gender, are often ‘spoken of as if they were discrete and separate categories’.[186] This ignores the fact that people occupy multiple categories of identity. Adopting a silo approach to hate speech requires incidents of hate speech to be classified under one category (ie, racist hate speech or GHS), which ignores the fact that ‘individuals are often targeted for simultaneously belonging to more than one target group’.[187]

However, this should not be considered an argument specifically directed against GHS regulation. Rather, this is a criticism of all hate speech legislation that adopts a silo approach, which may be seen as essentialising categories of hate speech and ignoring intersectionality.[188] As we have discussed in this article, GHS is best understood from an intersectional perspective, with an awareness that not all women are equally vulnerable to GHS or impacted by it in the same ways. Gendered norms and misogyny intersect with other axes of oppression such as disability, class, religion or sexuality. For example, lesbians ‘transgress both gender and sexuality norms’ and therefore experience unique forms of GHS.[189] However, simply because axes of oppression intersect in complex ways does not prevent us from recognising the ‘connections and commonalities’ in women’s experiences of GHS, and does not mean that power hierarchies on the basis of gender are not worth addressing through legal intervention or protections – and this includes legislation aimed at hate speech.[190]

Arguments regarding freedom of speech are beyond the scope of this article to the extent that they relate to hate speech regulation generally, rather than GHS in particular. However, one argument put forward by freedom of speech defenders against hate speech laws in general is important to the notion of GHS and how it operates. This is the ‘counterspeech’ argument; namely that ‘the best response to hate speech is for its targets and the community more broadly to answer back, to engage in more speech to discuss, and counteract, the hate speakers’ messages’.[191] One problem with this argument is the assumption that everyone has equality of speech. MacKinnon in particular decries the ‘lack of recognition that some people get a lot more speech than others’,[192] and as Gelber argues, this inequality of speech renders the ‘counterspeech of the subordinate less able to be heard’.[193] Responding to this concern, Gelber argues for a ‘supported version of counterspeech’ that fosters participation in speech for those previously prevented from doing so. Arguably, regulating GHS will not do this on its own, as GHS is only one factor contributing to gender inequalities of speech. But legislating against GHS would nonetheless be a powerful step towards creating an environment where women can participate in public discourse without being silenced on the basis of their gender.

Related to the role of counterspeech is a potential concern for hate speech legislation to shut down grassroots activism which takes the form of creative, activist or ironic engagements with hate speech itself. As Wasserman notes, ‘symbolic counter-speech [can comprise] a direct response to the symbol on its own terms, employing the symbol itself as the vehicle for the counter-message’.[194] Examples of such counterspeech may include SlutWalk events,[195] or individuals who embraced and re-claimed the language of ‘nasty woman’ during the 2016 United States presidential election.[196] In effect, this argument against prohibiting GHS expresses a concern for over-effective enforcement, or at least the potential for misguided enforcement. Such a concern may be addressed through the inclusion of a requirement for intention to cause harm, before liability under the relevant prohibition can arise. We saw an example of this in the federal criminal provisions outlined in Part III above: these provisions apply only where the urging of violence against an individual or group on the basis of a protected group identity is accompanied by an intention, or recklessness, that violence would occur as a result.[197] Civil hate speech laws also contain a subjective component: in most cases, it is ‘necessary to have “regard to the subjective purpose of the publisher”’ in determining whether civil hate speech laws have been breached.[198] Admittedly, an intention element corresponds more closely to the conservative definition of GHS as mapped out. More consistent with the progressive definition of GHS would be the incorporation of exceptions for artistic works, statements or discussions for genuine academic or artistic purposes or other genuine purposes in the public interest, as feature in the section 18D exceptions to the prohibition of racist hate speech in section 18C of the RDA. Our point here is not to debate the merits of an intention element or particular exceptions,[199] but to note that such options exist for addressing any potential over-inclusiveness of a prohibition on GHS.

In contrast to concerns about the possibility of overzealous enforcement of any legislative provision against GHS, a final possible argument against prohibiting GHS is the low likelihood of any such provision being effectively enforced. Certainly, as we saw in Part III, vilification legislation across Australia does not give rise to a great volume of legal actions, and the case of Eatock v Bolt[200] demonstrates the high threshold for a successful action even regarding ‘offensive behaviour’ rather than incitement. But this does not mean that such legislative provisions are pointless. On the contrary, their symbolic value is well documented – particularly their value to members of those groups protected by such laws.[201] Anti-vilification laws still send a powerful message by communicating to the broader community the unacceptable nature of such conduct, from the perspective not merely of one portion of the community, but of the state as purported representative of Australian society as a whole. Likewise, explicit legislative recognition and prohibition of GHS as a phenomenon – and as a practice considered reprehensible and unacceptable – would carry value independent of the frequency or effectiveness of its enforcement. Put bluntly, if poor enforcement of such a provision is a possibility, then that may be a battle to be fought once the provision exists: it is not a reason simply to avoid legislating at all.

This article has analysed a complex topic, namely the regulation of GHS in Australia. Our intention has been to critically analyse the failure to legislate (adequately) against GHS, and not necessarily to advocate for any specific scheme of legislative reform above other possibilities. Rather, this article is intended as a prompt for further analysis and debate regarding GHS, the harms it causes to women, and options for regulation.