University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

WHAT’S PLAINLY WRONG IN AUSTRALIAN LAW? AN EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS OF THE RULE IN FARAH

ANTONIA GLOVER*

In Australian Securities Commission v Marlborough Gold Mines Ltd [1993] HCA 15; (1993) 177 CLR 485, and again in Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (2007) 230 CLR 89, the High Court pronounced that Australian courts must follow the decisions of appellate courts across Australia unless convinced that those decisions are ‘plainly wrong’. This article seeks to track the development and application of this rule in both a historical and modern context. It first examines the state of the law prior to Marlborough and then engages in an empirical analysis of the use of the rule since Marlborough in 1993, tracking how often the rule has been used and where divergence between jurisdictions has emerged. The results confirm the existence of a judicial system with an increased focus on, and practice of, internal consistency. This replaces the 20th century paradigm in which loyalty to Britain was prioritised over intra-Australian uniformity.

In what has become a seminal statement, in Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (‘Farah’),[1] the High Court directed that on questions of law of national operation (ie the common law, uniform national legislation and Commonwealth legislation), the decisions of intermediate appellate courts (‘IACs’) must be followed by courts in other Australian jurisdictions unless the latter court is convinced that the IAC decision in question is plainly wrong (‘Farah plainly wrong rule’).

The statement in Farah was in large part a restatement of the High Court’s earlier pronouncement in Australian Securities Commission v Marlborough Gold Mines Ltd (‘Marlborough’), where the High Court expounded an identical rule but omitted reference to the common law.[2] Marlborough was the first instance in Australia’s history where the High Court had sought to clearly address the question of inter-jurisdictional Australian precedent. The preceding 92 years of a federated Australia had been marked by a quiet uncertainty on the subject.

The Farah plainly wrong rule has significant implications for the nature of Australia’s judicial federation. It creates formal and tight bonds between Australia’s numerous, distinct judicial hierarchies in respect of the increasingly broad domain of law of national operation. Despite its importance, there is a degree of uncertainty and confusion as to whether Farah marks a significant departure from the past, and how exactly it is being applied in the present. This article seeks to address that gap by tracking the development and practical application of the rule in both a historical and modern context. It proceeds in two primary parts.

The first part is qualitative. It examines how the complex question of inter-jurisdictional precedent[3] was approached in the century which preceded Marlborough. An analysis of this history demonstrates that the standardisation of the rules of precedent for extra-hierarchical Australian authority evident in Marlborough and Farah is the culmination of, and a product of, the severance of judicial ties with Britain and the abandonment of the ideal of pan-British Commonwealth uniformity.

The second part is quantitative. It examines exactly how courts have applied and relied on the Farah plainly wrong rule since Marlborough was handed down in 1993. The empirical analysis conducted examines how frequently courts have made reference to the rule, how frequently they have elected to diverge from prior authority on the basis that it is ‘plainly wrong’, and where exactly that divergence has emerged. The results show, as one would expect from a rule which imposes a general standard of uniformity with a limited exception, that the practice of courts has been to largely follow each other’s decisions except in restricted and careful circumstances. Only 20 decisions over the 25 years surveyed involved a court deeming a prior IAC decision to be plainly wrong. These decisions emanated from both single judges and IACs, and stemmed most strongly from the New South Wales (‘NSW’) Supreme Court (with 50% of the cases involving a finding that a prior decision was plainly wrong coming from NSW). The rate at which courts engaged with the language of the rule rose considerably over the studied period.

Taken cumulatively, this article seeks to demonstrate how, as Australia has severed ties with Britain and its Commonwealth neighbours, it has developed a new focus on, and practice of, internal consistency, with internal divergence carefully regulated by a High Court which sees jurisdiction-specific innovation as contrary to the system devised by the Constitution. The corollary of that trend has been, as James Stellios has remarked, the amplification of the national features of the federal judicial system and a marginalisation of the features that preserve the distinctiveness of the state and territory judicial systems.[4] This in turn has allowed courts such as the NSW Supreme Court to gain an even greater voice within the national judicial conversation.

Part II of the article provides background to the Farah plainly wrong rule and an explanation of its scope. Part III sets out the history of inter-jurisdictional precedent pre-Marlborough and Part IV sets out the results of the empirical study. Part V then offers some overarching conclusions.

This article is not designed as a support or critique of the Farah plainly wrong rule or as an overview of the uncertainties the rule has arguably engendered. These issues have already been extensively canvassed.[5] However, to provide the necessary background to the below analysis, this Part provides an overview of the key authorities and sketches the outer boundaries of the Farah plainly wrong rule.

The modern requirement to follow IAC decisions on questions of law of national operation developed over the course of three High Court cases, namely Marlborough, Farah and CAL No 14 Pty Ltd v Motor Accidents Board (‘CAL No 14’).[6]

Marlborough concerned the scope of the scheme of arrangement regime under the Corporations Law (then a uniform national statute). There had been conflicting authorities on the question in issue and the primary judge and the Full Western Australian Supreme Court had elected to follow a single-judge Victorian decision over obiter dicta of the Full Federal Court.[7] The High Court labelled this approach ‘somewhat surprising’, observing:

Although the considerations applying are somewhat different from those applying in the case of Commonwealth legislation, uniformity of decision in the interpretation of uniform national legislation such as the Law is a sufficiently important consideration to require that an intermediate appellate court – and all the more so a single judge – should not depart from an interpretation placed on such legislation by another Australian intermediate appellate court unless convinced that that interpretation is plainly wrong.[8]

While the High Court’s comments were confined to an analysis of uniform national legislation, the Court seemed to be operating on the assumption that a plainly wrong standard also applied to Commonwealth statute, albeit with ‘somewhat different’ considerations applying. That at least was how the decision was subsequently interpreted by the courts.[9]

The notion that a decision should not be departed from by a later court unless ‘convinced’ that it is ‘plainly wrong’ has a long history which considerably predates Marlborough. In 1913, Isaacs J concluded that it was the High Court’s ‘paramount and sworn duty’ to depart from its own prior constitutional decisions if they were ‘clearly’ or ‘manifestly’ wrong.[10] The High Court similarly applied a ‘clearly wrong’ standard to English Court of Appeal and House of Lords decisions intermittently in the first half of the 20th century, as is detailed in Part III.[11]

The NSW[12] and South Australian[13] Supreme Courts adopted a ‘clearly’ or ‘plainly’ wrong standard with respect to their own prior decisions decades before Marlborough.[14] Marlborough, however, represented the first time the High Court adapted the concept so as to apply it to the precedential ties between Australian court hierarchies, although as is discussed below, some lower courts had reached a similar conclusion in the preceding years.

Fourteen years after Marlborough in Farah, the High Court re-stated the applicability of a plainly wrong standard to decisions concerning both uniform national and Commonwealth statute. The High Court then went on to note that, ‘[s]ince there is a common law of Australia rather than of each Australian jurisdiction, the same principle applies in relation to non-statutory law’.[15] This process of reasoning reflected the High Court’s ‘single Australian common law’ jurisprudence that rose to prominence in the late 1990s.[16]

There had been earlier signs of this shift. In the judgment of McHugh J in Kable v Director of Public Prosecutions (NSW) (‘Kable’), his Honour had observed that ‘in exercising federal jurisdiction, a State court must deduce any relevant common law principle from the decisions of all the courts of the nation and not merely from the decisions of the higher courts of its State’.[17] Fitzgerald P (of the Queensland Court of Appeal) in 1999 and Kiefel J (as a single judge of the Federal Court) in 2005 also adopted the same process of reasoning as eventually employed in Farah, combining the reasoning of the ‘single common law’ cases with Marlborough to arrive at the conclusion that the plainly wrong standard applied to non-statutory law.[18]

While the decision in Marlborough passed with relatively little comment, Farah prompted a flurry of activity[19] largely provoked by Keith Mason’s retirement speech as President of the NSW Court of Appeal, where he launched a scathing attack on what he described as a ‘profound shift in the rules of judicial engagement’.[20] The extent of the reaction seemed to prompt the High Court’s comments a year later in CAL No 14, where the Court took the opportunity to reject the assertion that Farah represented any kind of drastic change. The Farah plainly wrong rule, according to the High Court, ‘has been recognised in relation to decisions on the common law for a long time in numerous cases before the Farah Constructions case ... [t]he principle simply reflects ... the approach which this Court took before 1986 in relation to English Court of Appeal and House of Lords decisions’.[21] The High Court went on to chastise the Tasmanian Supreme Court for failing to ‘carry out its duty to follow the New South Wales Court of Appeal’.[22]

The only additional comment the High Court has made on the issue since CAL No 14 was in R v Falzon, where the Court staunchly criticised the Victorian Court of Appeal for attempting to circumvent the application of the Farah plainly wrong rule through an ‘untenable’ attempt at distinguishing prior IAC authority.[23]

Despite extensive commentary on the Farah plainly wrong rule, its outer limits remain unsettled. References to the Farah plainly wrong rule have spread into contexts beyond those explicitly contemplated in Marlborough, Farah and CAL No 14, often with little acknowledgement of the difference in situation. Exploring the full scope of these uncertainties is beyond the scope of this article. For clarity, however, the following three aspects of the rule’s scope should be noted.

First, the Farah plainly wrong rule does not appear to make any distinction between the ratio decidendi of a decision and the obiter dicta. This is consistent with the reasoning in Marlborough itself, which was directly concerned with a court not following the obiter dicta of a prior IAC decision. Despite this, no distinction was made in Marlborough between the rule’s applicability to obiter dicta as against ratio decidendi, even though the trial judge in Marlborough explicitly relied on the fact that the relevant comments were obiter dicta in justifying departure from the prior decision.[24] This aspect of the reasoning in Marlborough does not seem to have been acknowledged in any subsequent decision. Nonetheless, the weight of authority has applied the rule to at least ‘well considered’ or ‘seriously considered’ obiter dicta.[25] For these reasons, no differentiation is made in subsequent discussion between the standard as it applies to ratio decidendi and as it applies to obiter dicta.[26]

Secondly, the Farah plainly wrong rule does not seem to apply to a court’s consideration of an IAC decision on similar or identical but non-uniform statute.[27] The rule has been frequently cited in that context, both with[28] and without[29] an acknowledgment of the difference in situation. This approach however, appears at odds with the direction of McHugh J in Marshall v Director General, Department of Transport (‘Marshall’),[30] as approved by a unanimous High Court in 2008 in Walker Corporation Pty Ltd v Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority (‘Walker Corporation’),[31] where it was emphasised that a court in one jurisdiction should not ‘slavishly follow’ decisions of extra-hierarchical courts in respect of ‘similar or even identical legislation’ as ‘[t]he duty of courts, when construing legislation, is to give effect to the purpose of the legislation. ... Judicial decisions on similar or identical legislation in other jurisdictions are guides to, but cannot control, the meaning of legislation in the court’s jurisdiction’.[32] A number of judges have noted the inconsistency between this direction and an application of the Farah plainly wrong rule.[33]

Finally, there is some suggestion that the Farah plainly wrong rule, or at least an equivalent plainly wrong rule, applies to situations involving single judges considering other jurisdiction’s single-judge decisions. The purported application of a plainly wrong standard to single-judge decisions pre-dates Marlborough to the 1982 case of Hamilton Island Enterprises Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (‘Hamilton Island’).[34] This approach has some high-profile proponents. Hayne,[35] Finkelstein[36] and Edelman[37] JJ have all endorsed the application of a plainly wrong standard in this context.

The application of a plainly wrong rule in either of these latter two contexts involves considerations which do not necessarily apply when considering the Farah plainly wrong rule in a strict sense. Accordingly, and in the interests of defining and confining this article’s scope, cases which fall within these latter two categories are excluded from discussion apart from where indicated.

As the shifts in emphasis and tone of Marlborough, Farah and Cal No 14 indicate, rules of precedent are fluid and actively created.[38] While obviously guided by the underlying constitutional requirements and norms of the polity in question, the rules that apply between countries or across federated (or equivalent) states are by no means a historical inevitability. In Canada, for example, the Supreme Court has flatly rejected the proposition that any precedential obligation applies between coordinate provincial courts despite a comparable judicial structure to that of Australia.[39] There is also a careful precedential delineation between the law of Scotland, the law of Northern Ireland, and the law of England and Wales for example, notwithstanding the shared ultimate appellate court.[40] The United States system is grounded on the strict independence of each state legal system, guided by the limited jurisdiction of the United States Supreme Court, though there is some suggestion that state supreme court decisions carry ‘super-persuasive’ status in other states with respect to common law and uniform national legislation.[41]

This Part sets out the history and the process by which Australia came to place such great emphasis on intra-Australian precedent and uniformity of decision-making as is borne out in Marlborough, Farah and the empirical results in Part IV. As the High Court indicated in CAL No 14,[42] to understand the pursuit of Australian-wide uniformity one must look to the pursuit of English-Australian uniformity, or more broadly, intra-Commonwealth[43] uniformity. It is that history, and the gradual abandonment of that ideal, that helps explain why the discussion of intra-Australian uniformity, and the corollary ideal of a single Australian common law, only really came to the fore in the 1980s and 1990s. The authority on the question before that was scant, vague and little-known and the precedence given to alignment with Britain meant that intra-Australian divergence could develop relatively unimpeded.

In 1877, an independently-minded NSW Supreme Court was tasked with considering the meaning of a Victorian statute worded identically to an Imperial statute. The NSW Supreme Court preferred the construction given to the statute in its own previous decision over the construction developed by the English Court of Appeal. The decision was appealed to the Privy Council, who in Trimble v Hill (‘Trimble’) issued a direction which would echo through the next 100 years of Australian precedential decision-making:

Their Lordships think the Court in the colony might well have taken this [English] decision as an authoritative construction of the statute. It is the judgment of the Court of Appeal, by which all the Courts in England are bound, until a contrary determination has been arrived at by the House of Lords. Their Lordships think that in colonies where a like enactment has been passed by the Legislature, the Colonial Courts should also govern themselves by it. ...

Their Lordships would not have felt themselves justified in advising Her Majesty to depart from the [Court of Appeal] decision ... unless they entertained a clear opinion that the construction it has given to the proviso in question was wrong,[44] and had not settled the law; since in their view it is of the utmost importance that in all parts of the empire where English law prevails, the interpretation of that law by the Courts should be as nearly as possible the same.[45]

In other words, courts across the old Empire should strive for uniformity, and that uniformity was to be achieved by looking in towards the English decisions and abandoning any colonial innovations.

A consistent line on what this quest for uniformity required of ‘colonial’ courts was never really reached. The Privy Council in 1927 suggested that colonial courts were bound to follow the House of Lords in preference to their own decisions,[46] but allowed a greater degree of latitude with respect to decisions of the Court of Appeal than had been suggested in Trimble.[47] The High Court rejected the proposition that it was bound to follow the English Court of Appeal in 1909 in Brown v Holloway,[48] but then affirmed that a contrary decision of the English Court of Appeal was sufficient reason to reconsider its own previous decisions on questions of both common law and statute in Sexton v Horton in 1926[49] and Waghorn v Waghorn (‘Waghorn’) in 1942.[50] In both cases, the High Court abandoned its previous decision and followed the English decision, stating that it was its policy to do so unless some manifest error was apparent in the English case.[51] The rationale behind both decisions was the need for pan-Commonwealth uniformity. As Dixon J declared in Waghorn:

[W]here a general proposition is involved the court should be careful to avoid introducing into Australian law a principle inconsistent with that which has been accepted in England. The common law is administered in many jurisdictions, and unless each of them guards against needless divergences of decision its uniform development is imperilled. Statutes based upon a common policy and expressed in the same or similar forms ought not to be given different operations.[52]

Dixon J again expressed this sentiment in Wright v Wright, describing diversity in the development of the common law as an ‘evil’,[53] a comment that was picked up by the High Court in CAL No 14 in justifying the decision in Farah.[54] Notably in Wright however, the Court considered the English Court of Appeal decision in question to be sufficiently erroneous to justify the High Court holding onto its pre-existing position.[55] Dixon J nonetheless held fast to his belief in a single ‘august corpus’ of pan-Commonwealth common law[56] until his decision in Parker v The Queen (‘Parker’) in 1963.[57] In Parker a particularly flawed House of Lords decision[58] compelled the then Chief Justice to declare that (notwithstanding the benefits of uniformity) House of Lords decisions should no longer be followed in preference to the High Court’s own decisions.[59] Isaacs J had reached the same position with respect to House of Lords decisions in 1925, rejecting an over-reliance on Trimble in view of the development of the ‘dominion courts’ in the intervening 45 years,[60] but it was not until Dixon CJ declared as much in Parker that the view began to stick. State supreme courts continued to affirm the obligation to follow English decisions as a general rule right through to the 1970s.[61] The final nails in the coffin of pan-Commonwealth uniformity only came with the Privy Council’s decision in 1969 in Australian Consolidated Press v Uren, where it recognised that Australian law could depart from the settled British common law position,[62] the High Court’s decision in 1978 in Viro v The Queen, where the High Court declared it was no longer bound by the Privy Council,[63] and finally in 1986 when appeals to the Privy Council from all Australian courts totally ceased.[64] Only at this point were ‘the last vestiges’ of Trimble finally abandoned.[65]

Thus until 1986 (with fading relevance at the end) the modern-day emphasis on pan-Australian uniformity was overshadowed by a superficially more ambitious goal – pan-Commonwealth uniformity. Under this system, British decisions with respect to the common law and at least similarly worded statutes were of equal precedential relevance to Australian courts as other Australian decisions. Technically, South African decisions and New Zealand decisions and Canadian decisions were also of equal relevance,[66] albeit without quite the same imperial lustre as those of the Motherland.

While theoretically the quest for pan-Commonwealth uniformity encompassed the attainment of intra-Australian uniformity of decision-making, the reality seemed to be that it hampered the attainment of the latter. Uniform decision-making requires a perfect system in which every decision-maker has access to every relevant decision. In a world before (or even with) internet legal databases, the chances of every court in the Commonwealth finding and following every relevant decision from each of the other component parts of the British Commonwealth seems close to nil. This gave rise to inadvertent conflict, allowing courts some latitude as to which decision to follow, and thereby prevented any seriously coherent attempt at achieving uniformity.

This problem was exacerbated by a British non-committal to the cause of pan-Commonwealth uniformity that its own Privy Council expounded. It was well-recognised that while Australian courts showed great deference to English decisions, English courts did not show the same deference to Australian (or other Commonwealth) decisions.[67] David Jackson observed in 1970, ‘[d]isagreement by an Australian court with an English view tends to be conscious and based on specific reasoning. Disagreement by an English court with an Australian view is, as often as not, in apparent ignorance that such a view exists’.[68] Similarly in Waghorn, Dixon J remarked on how it was ‘disappointing’ that the English Court of Appeal had proceeded to contradict a relevant High Court judgment in complete ignorance of its existence and cited a number of cases where a similar event had occurred.[69] In other words, the former colonial courts tried their best to comply with English decisions, and English courts simply did what they thought best.

This imperfection in the pursuit for uniformity had considerable practical implications for intra-Australian uniformity of decision-making. As will be seen in Part IV below, strict precedential rules demanding uniformity simply do not work where there is a pre-existing conflict of decision. An English disregard for Australian decisions seemed to produce a situation where an Australian Court decided X, an English court decided Y (paying little attention to antipodean developments), and then a different Australian court was faced with decisions X and Y, both of which attracted heightened deference. The latter Australian court was then forced to choose between imperial deference or intra-Australian camaraderie (or perhaps more simply, to pick whichever decision they preferred).[70] In this way the system simply collapsed under its own weight. Divergence within Australia could thrive so long as there was a marketplace of conflicting decisions which a particular Australian court could select from. Only in 1981 did King CJ in Bassell v McGuiness suggest that the ‘constitutional development of Australia as an independent sovereign nation’ should result in preference being given to Australian decisions over those of England in circumstances of conflict.[71]

Accordingly, no strong culture of intra-Australian uniformity of decision-making could really begin to grow until ties with Britain were finally severed and the traditional deference shown to British decisions over Australian ones could begin to fade. It therefore does not seem to be a coincidence that the first major wave of decisions emphasising the need for heightened precedential deference to extra-hierarchical Australian decisions emerged in the late 1970s and 1980s, just as the final ties to Britain were being shrugged off.

In CAL No 14, the High Court defended the application of the Farah plainly wrong rule to decisions on the common law by stating that the principle ‘had been recognised in relation to decisions on the common law for a long time in numerous cases before the Farah Constructions case’.[72] The High Court cited six cases in support of this proposition. One from 1953,[73] two from the 1980s,[74] and three from the post-Marlborough era.[75] In his defence of the historical basis for Farah, Justice Heydon similarly provided a list of historical cases adopting a Farah-like position with respect to the common law, Commonwealth statute and uniform national legislation.[76] The implicit (or explicit) argument was that those such as Keith Mason who were decrying Farah as a novel and far-reaching development were simply missing 50 years of case law saying the same thing. The historical reality appears slightly more complex.

Prominent articles on the precedential relationship between Australian courts up until the 1980s bore no mention of any particular rule of deference applying to the decisions of appellate courts of other Australian states or territories. Chief Justice Barwick in 1970, speaking extra-curially, referred to the fact that ‘[w]hilst some degree of comity in accepting one another’s decisions existed between the courts of the several colonies and now exists between the courts of the States, the decisions of the courts of one colony or State did not and do not bind the courts of another’.[77] According to Chief Justice Barwick, intra-Australian uniformity was achieved through the universal application of High Court decisions, not any rule of precedent between judicial hierarchies.[78] Lyndel Prott, in 1977, referred to a string of cases in the Queensland and South Australian Supreme Courts which expressed a willingness to reconsider a court’s own decision if another state supreme court disagreed, but that was as high as the obligation to extra-hierarchical IACs was put.[79] In 1980, AR Blackshield dismissed the proposition that any ties bound coordinate Australian courts together beyond mere comity.[80]

There were undoubtedly some pre-Marlborough calls for uniform decision-making between the state, territory and federal systems and some identification of a precedential obligation between each stretching beyond mere ‘respect’, ‘comity’ or ‘persuasiveness’. These authorities however tended to be little known and vague as to the exact obligation that applied.

Prior to 1975, commentary on the issue was particularly scant. In McColl v Bright, Gavan Duffy J described a NSW Full Court decision on a similarly worded statute as (while ‘technically it is not binding’) of ‘the strongest persuasive effect and should, in the absence of any decision to the contrary in the Full Court or the High Court, be followed by me’.[81] In 1953, the Tasmanian Supreme Court in Marshall v Watt agreed with Gavan Duffy J and relied on the High Court’s emphasis on pan-British Commonwealth uniformity as a justification for following a relevant Victorian common law decision. The Court however refrained from attempting to develop a formula ‘which better expresses [this] attitude’.[82] In 1955, in Sundell v The Queensland Housing Commission [No 4] (‘Sundell’), the Full Court of Queensland held that ‘where an interpretation has consistently been given to similar rules by other courts exercising similar jurisdiction to that invoked before us, I think we should follow those decisions’.[83] Notably in both Marshall v Watt and Sundell, the court was also seeking to comply with New Zealand decisions, evincing a continued emphasis on pan-Commonwealth uniformity.[84] There were also still some countervailing views. For example, in 1961 in Lord v Still, Else-Mitchell J declared that

differences in the case law of the several State jurisdictions in this continent cannot always be avoided but it is not the function of this court to rationalize the law of all States and, if uniformity is to be produced, the High Court of Australia is the appropriate tribunal entrusted with that task.[85]

It was not until the late 1970s and early 1980s that courts began more coherently to attempt to formulate a distinct precedential obligation applying between Australian jurisdictions. The context was clear. Ties with Britain were largely severed,[86] state courts were citing each other more and British courts less,[87] uniform national legislation was beginning to be introduced on a wider scale,[88] and the Commonwealth was asserting greater legislative power under the Constitution.[89] Thus Street CJ in R v Drysdale (a uniform national legislation case) started a wave in 1978 when he declared that a Full South Australian Supreme Court decision should be followed unless ‘affirmatively satisfied that it be wrong’ in the interests of ‘consistency in the application of the law throughout Australia’.[90] A similar formulation was then adopted with respect to single-judge Commonwealth statute decisions in Leary v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (‘Leary’) in 1980[91] and Hamilton Island in 1982,[92] and to appellate court Commonwealth statute decisions in R v Parsons in 1983[93] and R v Yates in 1991.[94] In Body Corporate Strata Plan No 4303 v Albion Insurance Co Ltd a ‘follow unless manifestly wrong’ formulation was adopted with respect to appellate court common law decisions.[95] Street CJ seemed to alter his Drysdale formulation slightly in R v Abbrederis in 1981 where his Honour held that appellate court decisions on Commonwealth statute should ‘as a matter of ordinary practice’ be followed unless departed from by the originating court or the High Court,[96] a formulation applied in O’Brien v Melbank Corporation Ltd[97] and R v Mai[98] amongst others.[99]

In other words, while there were some vague and little-known rumblings of a heightened precedential obligation applying between Australian jurisdictions prior to the 1970s, it was not until the last quarter of the century that courts began to start genuinely engaging with the issue on a larger scale. Even in the 1980s however, there seemed to be some confusion and conflict as to the exact obligation that applied. This confusion continued right up until the High Court handed down Marlborough in 1993 and (with respect to the common law) Farah in 2007.[100]

The regularisation of this previously scattered case law allows for an empirical tracking of the state of inter-jurisdictional precedent in a manner that is simply not possible with respect to the case law pre-1993. The lack of a cohesive rule prior to Marlborough and Farah means that that there are no clear case-based links that would allow for an accurate picture to be generated of the actual level of conformity and divergence between Australian jurisdictions as to law of national operation in that pre-Marlborough period.

The advent of the Farah plainly wrong rule however allows for such an analysis. This is significant as it permits an examination of not only the relevant rules with respect to where divergence between jurisdictions is permitted (rules which allow for certain assumptions to be made about the underlying level of divergence) but also of the actual level of inter-jurisdictional conformity on questions of law of national operation. This adds colour to what would otherwise be a purely qualitative analysis of the fact that the rules with respect to inter-jurisdictional conformity and divergence within Australia have seemingly become stricter and more consistent over time.

This Part accordingly examines the use of the Farah plainly wrong rule in practice, by empirically tracking the trends in the cases where the Farah plainly wrong rule has been engaged since Marlborough was handed down in 1993.

As a starting point, this analysis tracks the extent of the use of the Farah plainly wrong rule since Marlborough and the extent of the uniformity generated by the rule, setting out the frequency with which IAC decisions on questions of common law, Commonwealth statute and uniform national legislation were followed or departed from over the studied period.

The study then examines the make-up of that uniformity, by examining whether the frequency of divergence from IAC decisions varies based on hierarchical level (eg single-judge versus appellate courts), jurisdiction (eg Tasmania versus Victoria), or source or area of law (eg the common law versus Commonwealth statute). This sheds light on not only the extent of the uniformity generated by the Farah plainly wrong rule, but where exactly divergence is occurring.

This study operates as a systematic content analysis of the relevant sample of cases.[101] Cases which cited Marlborough, Farah and CAL No 14, and cases which drew on terminology developed in those cases, were systematically categorised and analysed to generate a broader picture of patterns in the ‘plainly wrong’ case law.

The study sits at the intersection of the extensive body of largely American empirical literature on the processes of judicial decision-making and practice[102] and the considerable number of empirical studies which have examined the citation practices of various courts.[103] This study differs from much of the former category of work which has largely considered how extraneous non-legal factors influence judicial conduct,[104] by focusing instead on how a legal rule has been applied and impacted by specifically legal jurisprudential factors. The study also serves to complement much of the Australian research pioneered by Russell Smyth into the citation practices of Australia’s various courts.[105] In contrast to Smyth’s work, this study looks to where divergence between Australian courts has emerged as against how frequently courts have cited each other.

In light of the relative novelty of the exercise, the study’s methodology was developed by reference to this general backdrop of empirical work[106] and in particular Mark Hall and Ronald Wright’s proposed methodological structure with respect to empirical analyses of case law.[107] The methodology can broadly be divided into two main stages: case selection and case categorisation.[108]

This study considers cases which consider the Farah plainly wrong rule from 6 May 1993 (the date Marlborough was handed down) to 31 December 2018.

The starting point of case selection was to collate and analyse every case which had cited Marlborough, Farah and CAL No 14 over the studied period. The Lexis Advance Casebase citator function was used to locate these cases. Of these 1393 cases, cases which cited Marlborough, Farah and CAL No 14 for reasons other than the plainly wrong rule were excluded. Only the principal state and federal superior courts were analysed in the interests of confining the study’s scope. Decisions of inferior courts and specialist courts such as the NSW Land and Environment Court were therefore not considered.

To capture cases which cited the Farah plainly wrong rule but did not cite an authority, a generic search of Lexis Advance was run over the same time period with the search terms ‘“intermediate appellate” and “plainly wrong”’ and ‘“intermediate appellate” and “clearly wrong”’. Of these 581 cases, decisions which used these terms in the Farah setting were included in the dataset.

For the reasons outlined in Part II, cases which involved single judges considering prior single-judge decisions or courts considering similar but non-uniform statute were not included in the analysis.

The following categories of cases were also excluded from the dataset:

• Cases where the court in question did not consider it necessary to reach a firm conclusion as to whether to follow or depart from the prior IAC decision (ie cases where the prior decision was distinguished or summary judgment and strike out application decisions[109]); and

• Appellate court decisions where only one judge considered the merits of the IAC decision in question, as the judge’s decision in such circumstances is of limited precedential weight,[110] and it is unclear whether the judge’s view would have commanded the weight of the majority had it been considered by them.

Cases which involved the application of the Farah plainly wrong rule to two wholly distinct legal issues within the same judgment were included twice. Similarly, the trial and appellate versions of a case were included as separate entries. This accounted for the possibility of divergence in approach on each issue or by each court.

Cases which considered a prior decision on a former version of legislation where a provision had been identically or almost identically re-enacted[111] were included in the dataset.[112] If the provision had changed in any substantive way,[113] the decision was not included. This reflects the obligation of the latter court to reach an independent conclusion regarding the meaning of the newly enacted provision.

In total, 324 cases were analysed for their substantive content. These cases will be described as cases in which the Farah plainly wrong rule was engaged.

Each case was analysed by reference to five metrics: jurisdiction, hierarchical position, area of law, source of law and approach to the prior IAC decision.

The first two metrics, jurisdiction and hierarchical position, were applied according to their plain terms. The category ‘appellate courts’ included courts sitting as full courts and supreme courts of appeal. It did not include single judges hearing appeals from lower courts.

Decisions were classed as involving a uniform national statute if the legislation considered appeared as ‘mirrored’ or ‘applied’ on the Australasian Parliamentary Counsel’s Committee’s ‘National Uniform Legislation: Acts of Jurisdictions Implementing Uniform Legislation’ database.[114] This database covers coordinate statutes that were enacted with an express harmonisation purpose.[115] ‘Common law’ was given its widest meaning as encompassing all unwritten law including equity – consistent with the use of the term in Farah and CAL No 14.[116] ‘Commonwealth statute’ covered legislation passed by the Commonwealth Parliament. Where a decision concerned Commonwealth statute that also formed part of a uniform national scheme, it was classed as considering uniform national statute.

The area of law was classified according to the area to which the specific plainly wrong issue related (eg defamation), and by reference to the predominant area based on the author’s judgement if two areas were raised on the same legal issue.

A five-degree classification process was adopted to measure whether the previous decision had been followed: followed; conflict – equal status; conflict – other binding precedent; not followed – plainly wrong; not followed – principle not applied. These five categories reflected the reality that despite the seemingly dichotomous nature of the Farah plainly wrong rule (a decision is followed or found to be plainly wrong) the reality is considerably more complex. Additional categories were therefore required to reflect this nuance.[117]

A decision was classed as ‘followed’ if the judge (or a majority of judges in an appellate decision) adopted the reasoning of the prior case in its own reasoning.

The ‘conflict – equal status’ classification applied in cases where the latter court was faced with two conflicting decisions on a legal issue which both attracted a heightened (but non-binding) level of deference. This covered cases where two IACs were in conflict (including the home appellate court) or where an IAC decision was in conflict with High Court obiter dicta.[118] ‘Conflict – other binding precedent’ covered cases where a court concluded that they were absolutely bound by a decision which conflicted with an extra-hierarchical IAC decision and that precedential obligation was found to override the Farah plainly wrong rule.

A case was classed as ‘not followed – plainly wrong’ if the prior decision was expressly found to be plainly wrong. ‘Not followed – principle not applied’ was applied where the latter court departed from the extra-hierarchical IAC decision in question without finding that it was plainly wrong. This covered cases, for instance, where the latter court did not consider that the Farah plainly wrong rule applied to obiter dicta and therefore did not feel the need to overcome the plainly wrong constraint in order to depart from the decision.

To account for errors in the case classification process, a random sample of 120 cases were re-classified by independent testers according to the above methodology.[119] Any divergences between the testers’ classifications and the author’s classifications were then re-checked to confirm their accuracy. All decisions other than those classed as ‘followed’ were also re-checked by the author at least once[120] as part of the qualitative analysis process.

The study tracks cases which have applied Marlborough, Farah and CAL No 14 or have used terminology borrowed from those cases. It does not track cases where courts may have cited, applied or disapproved of extra-hierarchical IAC decisions without noting the applicable precedential standard. It therefore does not capture cases for example where the application of the authority was so uncontested that there was no need to cite any applicable precedential rule (the effect of which is considered below), or where two decisions were in conflict such that the plainly wrong rule was of limited assistance.

This issue lessened in significance over the course of the studied period as the Farah plainly wrong rule became more widely known, reducing the risk that it was not applied where relevant. However, in the early years post-Marlborough the sample size is so small (1993: n=1, 1994: n=3) that the data cannot be taken to be a reliable marker of how courts approached IAC decisions over that period.

The case-selection process likely created a selection bias against cases where IAC decisions were followed. Cases where the prior decision’s merits were undisputed are less likely to have discussed the Farah plainly wrong rule in a manner which would have brought them within the sample. Decisions citing controversial cases however were more likely to be picked up as the parties were more likely to have actively disputed the prior decision’s correctness. The results are therefore likely to at least slightly understate the extent to which extra-hierarchical IAC decisions were followed.

This study also does not substantially cover cases concerning the approach of courts to common law decisions prior to Farah being handed down in 2007. As detailed in Part II, Marlborough did not refer to the common law, nor did the High Court expressly hold that there was a single common law across Australia until 1996.[121] Accordingly only 7 of the 89 pre-Farah cases relate to the common law. This study accordingly did not capture the vast majority of common law cases prior to 2007 where the Farah plainly wrong rule should have been engaged.

Ultimately all of these limitations stem from the fact that there is no clear mechanism to generate a reliable sample of cases where the issue of inter-jurisdictional precedent has arisen in the absence of clear terminological or case-based links. For the reasons outlined in Part V below however, it would seem that any changes with respect to the rate of usage of the language or citation of the Farah plainly wrong rule is of itself significant in terms of its effect on modifying judicial and practitioner behaviour. Accordingly, this fallibility in the methodology, while significant, does not seem to render the empirical exercise futile.

Finally, there are risks that come with studies such as this which attempt to distil complex judgments into neat definitional categories. This is particularly the case where the study’s subject matter involves judicial behaviour such that there are social and other overlays[122] which may lead to a chasm between what is said and unsaid in a judgment.[123] While the study’s methodology attempted to control for this as far as is possible, some nuance was necessarily lost. The study’s results should therefore be considered with these caveats in mind.

For context, it is helpful to begin with an overall picture of the use of the Farah plainly wrong rule since Marlborough was handed down in 1993.

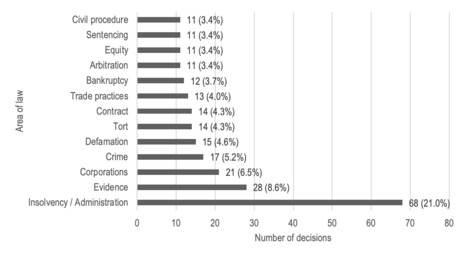

The number of cases in which the Farah plainly wrong rule has been engaged is depicted in Figure 1. The dotted line indicates the handing down of Farah in 2007.

Figure 1: Number of decisions in which the Farah plainly wrong rule engaged 1993–2018

There is a clear demarcation between the pre- and post-Farah era evident in the results. Between Marlborough and the decision in Farah, the number of cases in which the rule was engaged oscillated between 1 and 10 decisions per year with an average of 6.1 decisions. Farah however initiated a significant uptick in the use of the language of the rule, with the rule being engaged an average of 19.9 times a year from 2007 to 2018. Even if common law decisions are excluded (accounting for the only difference in plain terms between Marlborough and Farah), Farah had the effect of more than doubling the average number of times per year the rule was engaged (from 5.6 times per year to 12.7 times per year). This signals that there were a large number of cases between 1993 and 2007 where the Farah plainly wrong rule should have been referenced but was not.[124]

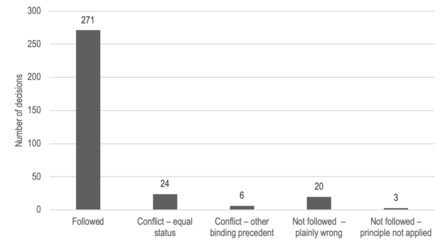

Figure 2 shows the 13 areas of law where the rule has been most frequently engaged over the course of the studied period.

Figure

2: Areas of law where the Farah plainly wrong rule most frequently engaged

(number of decisions / % of total)

Figure

2: Areas of law where the Farah plainly wrong rule most frequently engaged

(number of decisions / % of total)

Forty-nine discrete areas of law were identified in compiling the sample, indicating that the use of the Farah plainly wrong rule has spread into a wide range of practice areas.[125] There is, however, a clear clustering of cases around questions of the operation of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), or its Corporations Law precursor (covering insolvency and corporations law) and the heavily interrelated provisions of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth). When taken together, these three areas account for 31.2% of all studied decisions, over three times higher than the next most frequently engaged area of law (evidence at 8.6%). While the assessment of the relevant area of law left some room for subjective judgement (is a decision on the operation of insolvent trusts a question of the law of trusts or the law of insolvency?),[126] the starkness of the dominance of these areas indicates a clear concentration of the engagement of the Farah plainly wrong rule on questions of corporations, insolvency or bankruptcy law and therefore a high level of inter-court communication in these areas. This likely stems from the fact that corporations and insolvency matters tend to be heavily litigated in both the federal and state systems as both systems are assumed to possess the necessary expertise.

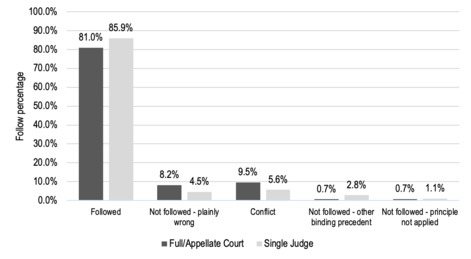

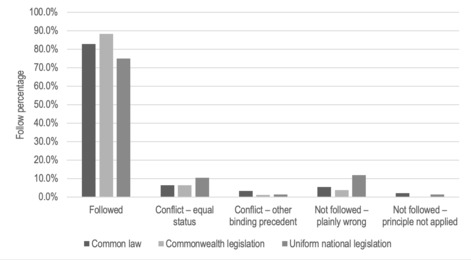

The approach of courts to decisions subject to the Farah plainly wrong rule over the studied period are set out in Figures 3 and 4.[127]

Figure 3: Approach of courts to extra-hierarchical IAC decisions (number of decisions)

|

|

Number of decisions

|

Percentage of total

|

|

Followed

|

271

|

83.6%

|

|

Conflict – equal status

|

24

|

7.4%

|

|

Conflict – other binding precedent

|

6

|

1.9%

|

|

Not followed – plainly wrong

|

20

|

6.2%

|

|

Not followed – principle not applied

|

3

|

0.9%

|

Figure 4: Approach of courts to extra-hierarchical IAC decision

As one would expect, in the vast majority (83.6%) of instances in which a court was presented with a decision of an extra-hierarchical IAC, that decision was followed. That figure may be somewhat higher, as noted above, to account for situations in which the decision followed was so uncontroversial that it was not picked up in the case selection process. The ‘followed’ percentage must also be considered in light of the 30 decisions which involved a court having no choice but to depart from at least one IAC decision due to a pre-existing conflict of decisions. If a court was faced with an extra-hierarchical IAC decision which did not conflict with any other decision, the follow rate was 92.2%.

Cases involving a ‘conflict – equal status’ classification occasionally arose due to an explicit finding in a previous decision that another jurisdiction’s decision was plainly wrong,[128] but more frequently seemed to be the product of longer-standing divergence between jurisdictions that had arisen independently of the Farah plainly wrong rule and possibly in ignorance of it.[129] The number of ‘conflict – equal status’ decisions remained relatively consistent over time however (varying between zero and three decisions per year), indicating that the issue of divergent lines of authority has not necessarily been reduced by the growing prevalence of the Farah plainly wrong rule.[130]

There was no clear approach that courts adopted when faced with decisions of two conflicting decisions of equal precedential weight. This reflects the long-standing uncertainty regarding the appropriate approach for courts to adopt in such circumstances.[131] Most courts simply asserted that they were entitled to reach their own conclusion as to the correct legal principle.[132] There was no particular preference for the more recent line of authority in situations of conflict (in 11 decisions the court followed the conflicting decision which arose earlier in time, and in 13 the court followed the later decision). In cases of conflict between a home jurisdiction IAC decision and an extra-hierarchical IAC decision, there was also no particular favouritism for decisions of the home jurisdiction (in six cases the court followed the home jurisdiction decision and in four they favoured the extra-hierarchical decision).

The six ‘conflict – other binding precedent’ cases all involved acceptance of the relatively uncontroversial proposition that the Farah plainly wrong rule had to yield to traditional concepts of binding precedent.[133] Robson J (of the Supreme Court of Victoria) is the only judge to have expressed any doubt about that approach, when his Honour concluded that he was bound to follow the ‘common law of Australia’ over a traditionally binding decision of his home Court of Appeal due to the High Court’s ‘single common law’ jurisprudence.[134] This conclusion, while having a certain force,[135] was flatly rejected on appeal.[136] No other court seems to have adopted such a view.

Only 20 cases in the 25-year period surveyed involved a finding that a prior decision was plainly wrong. Factors which influenced the conclusion to depart from a decision on this basis ranged widely. Key themes included: the existence of judicial or academic criticism of the prior decision;[137] an absence of authority following the prior decision;[138] the non-unanimity of the previous decision;[139] an absence of anterior reasoning in the prior decision;[140] a failure to draw the prior court’s attention to a relevant issue or statutory provision;[141] and a perceived inconsistency with High Court or other lines of authority.[142] These all reflect relatively well-established principles regarding the comparative weight that should be accorded to prior authority.[143] The Victorian and South Australian appellate courts were the most frequently found to be plainly wrong (both n=5), followed by those in Queensland (n=4), Western Australia (n=3), NSW (n=2), and the Full Federal Court (n=1).

The following results provide a jurisdictional and hierarchical breakdown of the approach of courts to extra-hierarchical IAC decisions over the studied period.

In Marlborough, the High Court directed that the Farah plainly wrong rule applied ‘all the more so’ to single judges.[144] One would expect therefore that single judges would depart from decisions subject to the Farah plainly wrong rule at a lesser rate than appellate courts. However, this is not borne out clearly in the results.

Figure 5: Approach of courts to extra-hierarchical IAC decisions by court position (%)

|

|

Full / Appellate Court

|

Single-Judge

|

|

Followed

|

119 (81.0%)

|

152 (85.9%)

|

|

Conflict – equal status

|

14 (9.5%)

|

10 (5.6%)

|

|

Conflict – other binding precedent

|

1 (0.7%)

|

5 (2.8%)

|

|

Not followed – plainly wrong

|

12 (8.2%)

|

8 (4.5%)

|

|

Not followed – principle not applied

|

1 (0.7%)

|

2 (1.1%)

|

|

Total

|

147

|

177

|

Figure 6: Approach of courts to extra-hierarchical IAC decisions by court position (number of decisions / %)

While single judges elected to follow prior IAC decisions at a slightly greater rate than appellate courts (93.8% of single-judge decisions were classed as ‘followed’ as against 90.2% of appellate court decisions in cases not involving conflict), the difference is not as marked as expected. There was also no statistically significant relationship between a court’s hierarchical position and its propensity to follow a decision rather than deem it to be plainly wrong (p=0.172). The hierarchical position of a court therefore does not appear to have a substantial impact on its likelihood to deem a prior decision plainly wrong.

In general terms, the statistical analysis conducted tested the possibility that, in this instance, variance in the results between single judges and appellate courts was the product of random chance rather than the influence of hierarchical position. This is measured by a p-value.[145] Future references to statistical significance and p-values are used in an equivalent sense.

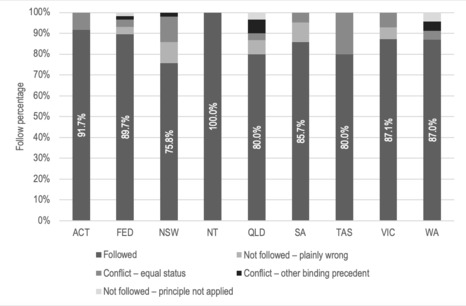

Figures 7 and 8 detail the approach of courts to decisions subject to the Farah plainly wrong rule by jurisdiction. Note that no Family Court decisions fell within the sample, indicating a significant degree of isolationism in the Family Court’s use of prior authority.[146]

Figure 7: Approach of courts to extra-hierarchical IAC decisions by jurisdiction (%)

|

|

ACT

|

FED

|

NSW

|

NT

|

QLD

|

SA

|

TAS

|

VIC

|

WA

|

|

Followed

|

11

|

52

|

75

|

6

|

24

|

18

|

4

|

61

|

20

|

|

Conflict – equal status

|

1

|

2

|

12

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

1

|

5

|

1

|

|

Conflict – other binding precedent

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

0

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

Not followed – plainly wrong

|

0

|

2

|

10

|

0

|

2

|

2

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

|

Not followed – principle not applied

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

|

Total

|

12

|

58

|

99

|

6

|

30

|

21

|

5

|

70

|

23

|

Figure 8: Approach of courts to extra-hierarchical IAC decisions by jurisdiction (number of decisions)

The most striking aspect of these results is the strong comparative propensity of NSW courts electing not to follow prior IAC decisions (at 10.1% of all NSW decisions), with NSW decisions representing 50.0% of all ‘not followed – plainly wrong’ decisions and only 30.6% of studied decisions. There is a statistically significant relationship between a case being heard in NSW and an extra-hierarchical IAC decision being deemed plainly wrong as against followed (p=0.0425).[147] On a percentage basis, the South Australian Supreme Court found extra-hierarchical IAC decisions to be plainly wrong at the next most frequent rate (2 of 21 or 9.5%). The Victorian and Queensland Supreme Courts, as the courts with the highest caseloads after those in NSW,[148] only found such prior decisions to be wrong 5.7% and 6.7% of the time respectively. The ACT, Northern Territory, Tasmanian and Western Australian Supreme Courts have never found another IAC decision to be plainly wrong as far as this study can establish.

As set out in Part II, the Farah plainly wrong rule applies to three distinct sources of law: common law, uniform national legislation and Commonwealth legislation.

Figures 9 and 10 set out the approach of courts to extra-hierarchical IAC decisions by source of law.

Figure 9: Approach of courts to extra-hierarchical IAC decisions by source of law (%)

|

|

Common Law

|

Commonwealth Legislation

|

Uniform national Legislation

|

|

Followed

|

77 (82.8%)

|

137 (88.4%)

|

57 (75.0%)

|

|

Conflict – equal status

|

6 (6.5%)

|

10 (6.5%)

|

8 (10.5%)

|

|

Conflict – other binding precedent

|

3 (3.2%)

|

2 (1.3%)

|

1 (1.3%)

|

|

Not followed – plainly wrong

|

5 (5.4%)

|

6 (3.9%)

|

9 (11.8%)

|

|

Not followed – principle not applied

|

2 (2.2%)

|

0 (0.0%)

|

1 (1.3%)

|

|

Total

|

93

|

155

|

76

|

Figure 10: Approach of courts to extra-hierarchical IAC decisions by source of law (number of decisions / %)

The source of law which generated the greatest amount of divergence was uniform national legislation, with 13.2% of decisions involving uniform national legislation involving a ‘not followed’ classification. A quarter (25.0%) of decisions on uniform national legislation involved some degree of controversy, either in the form of a court electing not to follow a decision or a finding of conflict. Commonwealth statute was the source of law which generated the least amount of divergence, with courts more likely to follow a decision (as against deem it plainly wrong) if it involved Commonwealth statute as against uniform national legislation (p=0.0204).[149]

These results can be better understood by considering the areas of law which were subject to some controversy.

Arbitration was the area with the highest number of ‘not followed – plainly wrong’ decisions (n=4 out of only 11 decisions)[150] followed by defamation and insolvency/administration (both n=3) and evidence (n=2).[151] Evidence and insolvency both had 6 decisions involving conflict, and defamation had 3. Overall, the 20 decisions which involved a ‘not followed – plainly wrong’ finding straddled 12 different areas of law.

Some of the spikes of divergence surrounding particular areas of law are readily explained by a concentration of controversy around certain individual prior decisions. For example, two ‘not followed – plainly wrong’ decisions on defamation concerned the Queensland Court of Appeal’s decision in Mizikovsky v Queensland Television Ltd (‘Mizikovsky’) regarding the correct approach to assessing defamatory imputations,[152] accounting for the comparatively high presence of plainly wrong findings amongst defamation decisions. Three of the ‘conflict’ evidence decisions concerned the Full Family Court decision in Ferrall v Blyton[153] which was considered erroneous and in conflict with High Court obiter dicta.[154] Two of the insolvency ‘not followed – plainly wrong’ decisions concerned the South Australian case of Hanel v O’Neill,[155] which was eventually expressly overturned by statute.[156] In circumstances where the overall number of cases involving controversy was relatively small, clusters such as these had the effect of making certain areas of law appear particularly prominent in sparking conflict or divergence.

There were three other primary triggers for divergence in certain areas of law. The relatively high number of evidence law decisions which involved controversy can in part be attributed to the 13-year delay in Victoria adopting the uniform evidence acts after the NSW and federal government did so in 1995. This meant that Victorian courts had 13 years of relative independence in the development of evidence law principle, which sparked issues once the systems became uniform.[157] Second, the concentration of arbitration decisions involving a ‘plainly wrong’ finding seemed to be the product of the difficulties stemming from the marrying of the judicial system with local and international arbitral systems, which operate on different assumptions and draw on different influences.[158] Taken along with the concentration of ‘not followed – plainly wrong’ defamation decisions concerning Mizikovsky, these two factors account for the large degree of controversy on questions of uniform national legislation. Finally, the relatively high degree of controversy on questions of insolvency/administration law can be explained by the pure volume of insolvency decisions involving an application of the Farah plainly wrong rule,[159] the major overhaul of insolvency law in 1992 which sparked a number of conflicting decisions in the ensuing decade,[160] and the decision in Hanel v O’Neill above which gave rise to two ‘not followed – plainly wrong’ decisions.[161]

Parts III and IV taken cumulatively indicate a steady uptake over the course of the 20th and early 21st century of at least the language of the plainly wrong rule and a growing doctrinal commitment to pan-Australian uniformity in place of the previous inconsistent and fractured emphasis on pan-British Commonwealth uniformity. At least in the post-Marlborough era, divergence between jurisdictions on questions of law of national operation has been rare, and courts have shown a high degree of reluctance in declaring prior IAC authority to be plainly wrong. Divergence has been more likely to arise in the context of a perpetuation of pre-exiting conflict than in a decision to deem a prior decision plainly wrong.

Importantly, the results in Part IV show a progressive growth in overall awareness of the Farah plainly wrong rule, indicating that the rule has become increasingly cemented into the national legal consciousness. As outlined in Part IV, between Marlborough in 1993 and Farah in 2007, the average number of cases per year that fell within the sample as engaging with the plainly wrong rule was 6.1. After Farah was handed down in 2007, the average number of cases per year in the sample was 19.9. Even if common law decisions are excluded, which accounts for the broader scope of the rule in Farah as against Marlborough, the Farah plainly wrong rule was engaged at more than double the number of times per year post-Farah (from 5.6 to 12.7 times per year).

In this respect it should be noted that the spike in number of decisions per year engaging with the Farah plainly wrong rule came not with the handing down of Farah in 2007, but in 2009, after Keith Mason’s retirement speech as President of the NSW Court of Appeal in 2008[162] and the associated academic[163] and judicial[164] debate. That is to say, the spike in the number of cases engaging with the plainly wrong rule only came after people started to talk about it. This sudden uptake implies that prior to 2009 there were cases where courts should have been engaging with the rule but were not. This does not appear to be an isolated incident. The High Court’s directions in Marshall and Walker Corporation not to ‘slavishly follow’ extra-hierarchical decisions on similar or identical state statute still seem to be languishing in a graveyard of forgotten precedential rules.[165]

There is, however, a valid question to be asked at this point. Namely, has the uptake in the language of the Farah plainly wrong rule as outlined in this article had a corresponding effect on the actual practice of courts in following or departing from each other’s decisions, and therefore the degree of conformity and uniformity within a federated Australia. There was, for example, no noticeable change in the number of ‘plainly wrong’ decisions per year over the course of the studied period notwithstanding the increase in the use of the language of the rule over that time.

As noted in Part IV, there does not seem to be a way of empirically comparing the actual degree of uniformity of Australian courts on questions of law of national operation pre- and post-Marlborough. There accordingly can be no definitive empirical answer to the question of whether a change in the applicable rule has entailed a change in actual behaviour when it comes to intra-Australian uniformity of decision-making. However, there are three key theoretical answers to this question which would seem to indicate that the shifts in precedential obligations over the course of the 20th century have in fact had a corresponding practical impact of reducing intra-Australian divergence.

The first answer is relatively basic and was prefaced in Part III. The removal of the obligation to follow British decisions at the expense of Australian decisions, and the cementation of the obligation to follow Australian decisions, reduced the size of the marketplace of cases to which a heightened precedential obligation applied. This in turn reduced the capacity for inadvertent conflicting decisions in the manner outlined in Part III, which in turn reduced the likelihood of intra-Australian divergence.

The second answer is similarly straightforward. The Farah plainly wrong rule imposes a positive obligation on practitioners and courts to find and follow prior extra-hierarchical IAC authority. While such authority would always have been relevant, by imposing such a positive obligation such prior authority is less likely to be missed by sheer omission.[166] This in turn enhances uniformity.

The third answer relies on the assumptions that can be made about the coercive force of a loose and ill-defined obligation of ‘comity’ between Australian courts as against the coercive force of a clear-cut obligation set out in strong terms by the High Court. Most courts would likely follow considered decisions of extra-hierarchical IACs irrespective of the existence of the plainly wrong rule the vast majority of the time. Any changes in behaviour as a result of the Farah plainly wrong rule are therefore realistically confined to those marginal cases where a court has some reservations about the desirability of perpetuating what may be perceived to be a flawed prior IAC decision, and where that court is considering preferencing a new approach over the perpetuation of that perceived error.

It is in that grey zone that the standardisation of the rules of inter-jurisdictional precedent would seem to have an important effect. The starting point in this analysis is to consider how rules of precedent operate to coerce judicial behaviour. Neil Duxbury, drawing on HLA Hart’s work on the ‘internal point of view’, argues that ‘[w]hen judges follow precedents they do so not because they fear the imposition of a sanction, but because precedent-following is regarded among them as correct practice, as a norm, deviation from which is likely to be viewed negatively’.[167] Judges, according to Duxbury, are engaged in a common enterprise and ‘accept the rules which apply to that activity as standards for the appraisal of their own behaviour and the behaviour of other judges’.[168] Economic and behavioural analyses of decision-making have affirmed this view. It has been increasingly recognised that judicial decision-making must be understood within a framework of interdependence between judges, reputational interests, and a desire for conformity with professional norms.[169] In other words, a judge is less likely to deviate from prior authority where they consider compliance with that authority to constitute ‘correct behaviour’ and they believe they will be criticised for divergence without proper cause.

On this view, there is no sharp delineation between ‘binding’ and ‘persuasive’ precedent and ‘precedent’ as against ‘judicial comity’. Rather, all prior judicial authority exists within a sliding spectrum and the weight to be given to a prior decision by pure force of what it is[170] will depend on a complex (often subconscious) calculus as to what extent the prevailing norms of the particular time require conformity (or permit deviation). Thus, an English High Court decision has always been merely ‘persuasive’, but deviation from such a decision is far more permissible today than it was in 1895.[171]

In that zone of arguably problematic prior decisions, there is therefore a considerable difference between the authoritative weight to be given to an extra-hierarchical IAC decision in 1965 when there was no clear commonly accepted standard to be applied, and in 2009 when the High Court in CAL No 14 had publicly denounced the Tasmanian Full Court for failing in ‘its duty’ to follow the NSW Court of Appeal unless ‘plainly wrong’.[172] There is a considerable difference between a world in which Chief Justice Barwick is making speeches on precedent asserting state courts’ rights to diverge from each other[173] and one in which High Court justices are extra-curially defending lower courts’ obligation to conform.[174] In the former situation, the duty to strive for pan-Australian uniformity had not been solidified as correct judicial practice, and therefore lacked serious coercive force, whereas in the latter, the coercive force could not be more strident. The cementation of the Farah plainly wrong rule in this manner would therefore seemingly operate to push more of those grey-zone cases into the category where they will be followed irrespective of their perceived flaws, and thereby would seem to further cement the practical existence of uniformity within Australia on questions of law of national operation.

For these reasons it would appear that the growth in the use of the language of the Farah plainly wrong rule documented in this article has entailed a corresponding solidification of the practice of intra-Australian uniformity of decision-making. Pan-Australian uniformity on at least law of national operation has become a mainstream judicial norm. Australian courts have become more dependent on each other as Australia has developed as a nation, as against say Canada where they have become less,[175] and the US which has always maintained a far greater degree of state-based independence.[176]

This has important implications for the nature of Australia’s federation as it strides into its second century. The Farah plainly wrong rule loosens (but does not entirely destroy) the distinctiveness of the ten distinct judicial hierarchies operating within the Australian federal judicial structure. The primary exceptions are the isolationism of Family Court hierarchy, which remains curiously silent in engaging with the Farah plainly wrong rule,[177] and the continued prioritisation given to home jurisdiction appellate courts by single judges in circumstances of conflict.[178] In the vast majority of cases however, the existence of the Farah plainly wrong rule, combined with the reticence of courts to engage with the limited exception provided,[179] renders hierarchical boundaries practically irrelevant when it comes to law of national operation. As Matthew Harding has observed, Farah marked a departure from a system where ‘judge-made law in each state and territory was ... conceived along lines emphasising the federal character of our system of government’.[180] According to James Stellios, this is consistent with a broader trend within Australian federalism, in which the national features of the judicial system have been amplified, and the features that preserve state-based distinctiveness (or ‘confederal’ features) have been marginalised.[181]

The corollary of that blurring of jurisdictional lines seems to be the amplification of the voice of Australia’s primary judicial hubs, particularly that of NSW. The NSW Supreme Court appears to be, though to a lesser extent, a modern-day England. In 2005 (the most recent statistics available), the NSW Supreme Court cited the least amount of interstate authority by a considerable margin (at 8.95% of citations followed by South Australia at 14.51% and Queensland at 15.16%),[182] and simultaneously was by far the biggest provider of coordinate citations to interstate courts (at 44.71% of total state supreme court coordinate citations, followed by Victoria at 21.51% and Queensland at 14.00%).[183] While the dominance of NSW in terms of its proportionate supply of interstate citations was relatively consistent over the 100 years Russell Smyth and Dietrich Fausten surveyed, the large-scale increase in the overall number of interstate citations over that period renders the NSW Supreme Court far more influential in the 21st century.[184] As the results of this study show, the NSW Supreme Court is also the most likely to deem other courts to be plainly wrong, with 50% of all plainly wrong decisions emanating from that court. Just like English courts in the mid-20th century, other courts look in and the NSW Supreme Court looks out to a far lesser extent.

Rodney Mott, writing in 1936 in the United States context, observed that it is ‘axiomatic that some supreme courts are more influential than others ... That this process of appreciation or depreciation is usually unconscious, and frequently irrational, does not make the prestige which results from it any less real or less potent a factor’.[185] If the 21st century is the century of pan-Australian uniformity of decision-making, and an increasing blurring of lines between jurisdictional hierarchies, then the side-effect of that trend seems to be that courts will increasingly coalesce around the most influential courts as their own courts lose the jurisdictional loyalty they once more stridently attracted.

Well-reasoned critique or defence of the Farah plainly wrong rule requires, as a starting point, an understanding of how the rule is being used and how that status quo differs from what came before. This article aimed to address that gap.

The results of the study show a steady growth in the use of the language of the Farah plainly wrong rule over the 25 years surveyed, particularly post-Farah in 2007 and the academic discussion that followed. Within that context, departure from extra-hierarchical IAC authority on the basis that it is plainly wrong has been occasional in NSW, rare in Victorian, Queensland, South Australian and Federal courts, and unheard of anywhere else. Departure has also not been confined to appellate courts, with the occasional single judge showing a willingness to make the quite bold pronouncement that their extra-hierarchical appellate counterpart was plainly wrong.

This growth in the acceptance of the Farah plainly wrong rule since 1993, and the corresponding reluctance of courts to make use of the plainly wrong exception, demarcates the present era from the one that preceded it. Much of the 20th century was marked by a desire to conform with Britain that overwhelmed the pursuit of pan-Australian uniformity. The modern-day High Court’s emphasis on pan-Australian uniformity above all else has rendered that imperial loyalty all but forgotten. As the outer boundaries of the Farah plainly wrong rule solidify in the national legal consciousness, the inter-hierarchical integration that the rule promotes seems likely only to grow.

|

Chief Executive Officer of Customs v Labrador Liquor Wholesale Pty

Ltd [2001] QCA 280; (2001) 188 ALR 493

|

|

Commissioner of the Australian Federal Police v Lee [No 2] [2016]

NSWSC 1131

|

|

Re Amerind Pty Ltd [2018] VSCA 41; (2018) 54 VR 230

|

|

Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Australian Building

and Construction Commissioner (2018) 259 FCR 20

|

|

Director of Public Prosecutions (Vic) v Patrick Stevedores Holdings Pty

Ltd [2012] VSCA 300; (2012) 41 VR 81

|

|

Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v Thomas [2016] VSCA 237; (2016) 53 VR

546

|

|

Einfeld v HIH Casualty & General Insurance Ltd [1999] NSWSC 867; (1999) 166 ALR

714