|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal Student Series |

DATA PROTECTION FOR BIOLOGICS – SHOULD THE DATA EXCLUSIVITY PERIOD BE INCREASED TO 12 YEARS?

JENNY WONG

Data exclusivity refers to the period in which data submitted by the first applicant to a regulatory agency, as evidence of the safety and efficacy of a new pharmaceutical or biopharmaceutical product for registration, cannot be used by subsequent applicants to obtain regulatory approval for an equivalent or similar product.[1]

Data exclusivity for biologics – therapeutic compounds manufactured using a biological process – was recently the focus of intense global media scrutiny during the final stages of negotiations of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Trade Agreement (TPP). The TPP is a trade agreement with the aim of achieving multiple aspirational goals, and amongst other things, aimed at promoting trade, investment and innovation between its 12 member countries.[2] On 5 October 2015, after more than 5 years of negotiations, an agreement between the 12 member countries was finally reached over the terms of the TPP. One of the final points of contention, up until the eve of the agreement being reached, was over the data exclusivity period for biologics. The United States (US) sought for the TPP to provide a longer period of protection for biologics, seeking a 12 year protection period so that the TPP would be aligned to the data exclusivity period afforded by US legislation.[3] This was met with opposition by other member countries, particularly Australia and New Zealand.

Under current Australian laws, biologics are provided a 5 year period of data exclusivity, the same period afforded to small-molecule drugs.[4] Representatives from both countries argued that an exclusivity period of 5 years was sufficient to balance the potential cost savings from price competition from biosimilars with long term incentives provided to entice investment and innovation. Moreover, the 5 year period was stated to be necessary to reduce pharmaceutical costs and the burden on state-subsidised medical programs such as the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) (Australia) and Pharmac (New Zealand).[5]

The dispute over the term of the data exclusivity period for biologics was ultimately resolved through a compromise with some members, such as the US, agreeing to data exclusivity periods of up to 8 years while others, such as Australia and New Zealand, committing only to a maximum period of 5 years.[6] While the compromise enabled the TPP to finally reach a conclusion, the dispute between the US and others over the data exclusivity period left an important question unanswered – whether there is justification to increasing the length of the data exclusivity period to 12 years.

The outcome of the TPP was met with discontent from US pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry groups who were lobbying for 12 years of data exclusivity for biologics. Industry representatives argued that protection periods falling short of 12 years would stifle investment and innovation into the research and development of biologics and new medicines as it would limit the opportunities for innovators to recoup development costs, reduce product sales and gross profit margins, and accordingly, remove incentives for innovators to invest in risky, expensive, and time-consuming drug development processes.[7] However, these arguments are likely to be exaggerated and in this thesis, I will provide evidence to show why there is little if any justification to support an increase in the period of data exclusivity for biologics. This thesis begins in Section 1 by discussing what biologics are and why rights conferred by data exclusivity are particularly important for protecting biologics. In Section 2, this thesis will use data from company financial reports to demonstrate that originator biologic sales as well as the profits earned by their corresponding manufacturers are not significantly impacted by biosimilar competition. In Section 3, this thesis will provide evidence to show that innovation from the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors are unlikely to be impacted by biosimilar entry into the market. Finally, Section 4 will discuss the evidence presented in this thesis in context with the developments thus far arguing for and against the justification of setting a 12 year data exclusivity period.

The term “biologics” generally refers to a class of complex compounds that are manufactured using biological, as opposed to chemical processes. They are an important and innovative development in the pharmaceutical industry and a step towards the creation of new medical indications and personalized medicine.[8] In comparison to the small-molecule drug market, which has been in steady decline since 2012, the biologics market has reciprocally enjoyed rapid growth with value sales in Europe being recorded at 5.5% compared with total market growth of 1.9%.[9]

In 2014, the global biologics market was valued at $US161 billion and by 2020, global sales are projected to reach an estimated $US287.1 billion.[10] While these figures appear staggering, it is not surprising when considering that a number of biologics accrue annual sales of more than $US1 billion. For instance, in 2014, AbbVie earned approximately $US13 billion worldwide from its blockbuster biologic, Humira; Johnson & Johnson, Merck & Co and Mitsubishi earned approximately $US8.8 billion off Remicade; and Amgen, Pfizer and Takeda earned approximately $US8.9 billion from Enbrel.[11]

A major issue currently faced by the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries is that a wave of major patents on first generation (originator) biologics, have or will expire, reaching a “patent cliff”. The term “patent cliff” refers to the expected decline in pharmaceutical company revenues as patents granting exclusivity over biologic drug treatments reach expiration. By 2020, 12 originator biologics with global sales worth more than $US67 billion will see their patent rights expire, opening up opportunities for manufacturers to market their own versions of the biologics and increase industry competition.[12]

The profitability of originator biologics coupled with the expiration of their substantive intellectual property protection incentivises rival manufacturers in the industry to gain entry by developing and marketing similar biopharmaceutical products, which are generally referred to as “biosimilars”. Biosimilars treat the same conditions as the original biologic but, unlike small-molecule generic drugs, they are not identical to the original product. Generic drugs are chemically synthesized and designed to be copies of the original brand name drug, eliciting the same pharmacological effects. However, a biosimilar is at most “highly similar” to the original biologic. Like biologics, biosimilars are manufactured using biological processes, such as living cells, and since the two differ in the living cells used in their manufacture, differences will inevitably arise in their biochemical, pharmacological and clinical behavior.[13]

Despite being a latecomer to the industry, analysts predict that the biosimilar market could potentially become the single fastest growing market in the pharmaceutical sector, with an estimated worth between $US11-25 billion in global sales projected for 2020.[14] The lucrative nature of the biosimilar market has since stimulated interest in non-conventional pharmaceutical investors, including Fujifilm, Samsung and Google, as well as countries with emerging markets such as China, India, Brazil, Mexico, South Korea, Russia and Turkey, which view biosimilars as a mechanism to drive macroeconomic growth.[15] Accordingly, manufacturers of originator biologics are keen to keep their competitors out of the market.

Data exclusivity is arguably a form of intellectual property which stands separate and distinct from the well-known traditional forms of intellectual property protections, such as patents.[16] As with small-molecule drugs, there are two main types of intellectual property protections for biologics – patents and data exclusivity. Both forms of protection serve distinct purposes and protect intellectual property in complementary ways. Patents protect inventions and innovations that meet the standards of patentability. In general, the subject matter to be patented must be novel, not obvious, useful and have economic utility. Patents can protect inventions and innovations ranging from breakthrough discoveries to incremental improvements.[17]

The data exclusivity period does not relate to the period of patent protection. Rather than protecting the invention, data exclusivity protects the data generated through use of the invention. It is distinct from patent protection in that it takes into account the time and financial investment taken to establish an invention or innovation. This includes preclinical and clinical trials conducted to ensure that therapeutic products meet safety and efficacy requirements. For both small-molecule generic drugs and biosimilars, legislation allows for an abbreviated pathway to gain regulatory approval. Rather than having to reconduct the clinical trials of the reference biologic, manufacturers of biosimilars are permitted to use the safety and efficacy data from preclinical and clinical trial testing of the reference product to show similarity in clinical and pharmacological effects.[18]

While the abbreviated approval process for biosimilars is beneficial for a number of reasons (such as reducing waste from repeat trials, encouraging competition, and lowering the cost of treatment) manufacturers of originator biologics are less than impressed, lobbying governments to preserve their incentives to innovate. Accordingly, data exclusivity provisions have been included into most legislation allowing for an abbreviated approval process for biosimilars.[19] As such, statutory provisions for data exclusivity creates an artificial monopoly for manufacturers of an originator biologic by preventing rival companies from using the originator biologic’s safety and efficacy data from preclinical and clinical trial testing to assist them in obtaining marketing approval. Within the protected period, regulatory authorities cannot, without the permission from the manufacturer of the originator biologic, use the initial preclinical and clinical data submitted to assess an application for biosimilar registration. It should be noted that the data exclusivity period does not prohibit a biosimilar manufacturer from carrying out their own trials and submitting their own data within the data protection period. However, it would be too costly and time-consuming to independently generate the comprehensive preclinical and clinical trial data of the original biologic. Accordingly, the net result of data exclusivity works in favour of the originator, which is to delay entry of biosimilars into the market.[20]

Because the terms of patent protection and data exclusivity are different and patent protection is much longer than data exclusivity periods, in many instances, the data exclusivity period will expire well before the primary patents of a pharmaceutical product. Once the period of data exclusivity expires, there is no bar to competitors using part or all of the preclinical and clinical data of an originator biologic to assist them in obtaining regulatory approval for their competing products.[21] Accordingly, manufacturers seek longer protection periods to close the gap between patent and data exclusivity terms.

In Australia, the data and market exclusivity protection afforded to therapeutic goods, including biologics and small-molecule drugs run concurrently. Section 25A of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) provides a protection period of 5 years starting from the first day of the therapeutic goods becoming registered.[22] Similarly, countries including New Zealand, Japan, Singapore and South Korea also provide the same concurrent data and market exclusivity protection to biologics and small-molecule drugs. While New Zealand has also imposed a similar 5 year protection period to Australia, Japan and South Korea have implemented protection periods of up to 6 years.[23]

In the US, biologics and small-molecule drugs are subject to different premarket pathways and intellectual property protections. Whereas small-molecule drugs are regulated by the Hatch-Waxman Act, biologics are regulated through the Public Health Service Act, which references 42 U.S.C § 262, and has since been amended by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act, which is part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.[24]

The Hatch-Waxman Act was designed to balance the competing demands of encouraging generic competition in the small-molecule drug market, but at the same time provide incentives for innovators to invest and develop new drugs.[25] When the Hatch-Waxman Act was enacted, it became one of most significant pieces of legislation to grant data exclusivity.[26] The Hatch-Waxman Act established a regulatory pathway for the approval of small-molecule generic drugs and provided various types of statutory exclusivities, including a 5 year data exclusivity period to original drug manufacturers.[27] The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act is intended to provide a similar regulatory framework and protection incentives for biologics and biosimilars.[28] Under the current US legislative requirements, biologics are provided up to 12 years of data exclusivity protection, of which 4 years is for data exclusivity and 8 years is for market exclusivity. While this is effectively a 12 year protection period, after 4 years a competitor firm is permitted to file an application for a biosimilar under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act; but the application would not be eligible for approval until after the 12 year period has expired.[29]

In Canada, a maximum protection period of 8 years is provided in the Guidance Document: Data Protection under C.08.004.1 of the Food and Drug Regulations. Of the 8 year period, 6 years covers the data protection period and an additional 2 years is provided for market exclusivity.[30]

In Europe, biologics and small-molecule drugs follow the 8+2+1 rule, which entitles manufacturers of originator biologics up to 8 years of data exclusivity and an additional 2 years of market exclusivity. Accordingly, firms may not submit applications for biosimilar registration that relies on an originator biologic’s data until 8 years have passed since its authorisation and are further prevented from marketing biosimilar products until after 10 years (i.e., 8+2). Unlike most other countries, the period of exclusivity can be further extended by an additional year for a maximum of 11 years (8+2+1) in the event that, during the first 8 years of the data exclusivity period, the originator biologic manufacturer obtains an approval for new therapeutic indications capable of bringing significant clinical benefits when compared to existing therapies.[31]

Of the countries providing data exclusivity, Australia and New Zealand grant some of the shortest periods whereas the US grants one of the longest. Considering that the US is the largest global market for pharmaceutical products and is purportedly the leader in biopharmaceutical research (conducting the majority of global research and development in pharmaceuticals as well as holding intellectual property rights over most new medicines),[32] it is not surprising that they would lobby for longer protection periods. But whether longer data exclusivity periods are required will be explored in the following sections.

The pharmaceutical industry invests an enormous amount of capital into research and development to bring new medicines to market. At present, pre-approval costs of developing a biologic are estimated to range between $US58 million and $US1.2 billion. Given the size of the expenditure, innovators will only be incentivised to invest if opportunities are available to recoup expenses and make a substantial profit. For instance, once a pharmaceutical product enters the market, patent protection and data and market exclusivity can result in gross profit margins exceeding 90%.[33] However, when intellectual property protections expire, rival manufacturers can offer interchangeable products at substantially discounted prices, sometimes at around 30%, and accordingly, impact negatively on the sales and gross profit margins of the brand-name originals.[34]

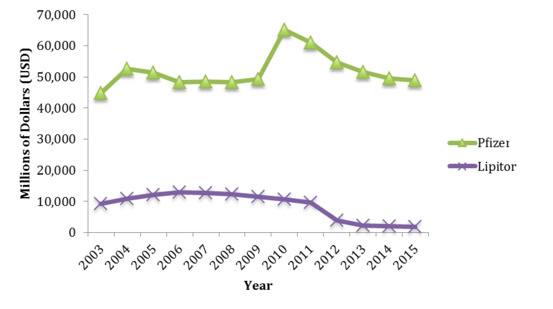

A notable example of the impact that generic drugs can have on an originator’s profit margins is from Pfizer’s blockbuster anti-cholesterol drug, Lipitor. After Lipitor fell off the patent cliff in 2011, its sales decreased by 60% as a result of competition from generics.[35] The overall revenue earned by Pfizer fell accordingly with worldwide Lipitor sales dropping from $US9.6 billion in 2011 to $US3.9 billion in 2012. Lipitor sales then continued to decline, falling to about $US3 billion in 2015.[36] Given the extensive impact of generics on a company’s overall economic performance, manufacturers of originator biologics fear a similar threat posed by biosimilars and are thus keen to keep their competitor’s biosimilar products off the market.[37]

If biosimilars were to pose a significant threat to the net sales of an originator biologic, we would expect to see a decrease in sales similar to the decline in Lipitor. However, this is not evident when consideration is had for the impact of the biosimilar, Omnitrope (Novartis/Sandoz) on the revenue generated from worldwide sales of the originator biologic, Genotropin (Pfizer).

Genotropin is a somatropin biologic created by recombinant DNA technology used to treat pediatric patients affected by growth failure resulting from an inadequate secretion of an endogenous growth hormone. Omnitrope was the first biosimilar to Genotropin to receive marketing authorisation in Australia, the European Union (EU) and US. In Australia, Omnitrope received authorization in September 2004 where it was then launched in November 2005. Shortly after, the European Commission granted marketing authorisation for Omnitrope in April 2006 with subsequent launches occurring in Germany, UK and Netherlands during the same year. In the US, Omnitrope was granted regulatory approval in mid-2006 and following the expiry of Genotropin’s patents in 2008, Omnitrope was launched in Canada and Japan in 2009.[38]

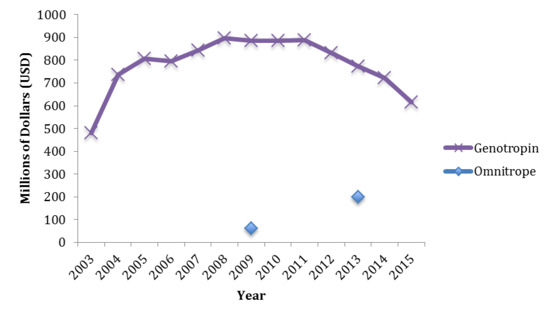

In contrast to an expected decrease in Genotropin sales, the entry and launch of Omnitrope into the worldwide biopharmaceutical market had little impact on Genotropin sales. In fact, the revenue generated from Genotropin sales increased in 2004 and continued to climb till 2008 where it then remained steady until after 2011 (Figure 1).[39]

Figure 1. Revenue generated from Genotropin sales from 2003 to 2015

compared to Omnitrope sales in 2009 and 2013.

Figure 1. Revenue generated from Genotropin sales from 2003 to 2015

compared to Omnitrope sales in 2009 and 2013.

When Omnitrope first entered the market in 2006, it struggled to gain market share. It was initially priced at a 33% discount based on the wholesale acquisition cost[40] compared to Genotropin, which at the time was the most widely used biologic in its class. By 2008, the discount was increased to 45%.[41] While the revenue generated from Omnitrope has steadily increased since 2006, earning $US60 million and $US200 million in 2009 and 2013 respectively, in comparison to Genotropin’s sales in 2013, the revenue generated from Omnitrope sales is more than 3.5 times lower than that of the originator biologic (Genotropin $US772 million vs Omnitrope $US200 million).[42]

On examination of Pfizer’s worldwide revenue over the same time periods, trends in Genotropin’s worldwide sales were not reflected in the overall changes of Pfizer’s total revenue profile (Figure 2). In fact, from 2004 to 2009, Pfizer had consistently earned between $US43 to $US47 billion worldwide, with a sharp increase and peak in global earnings in 2010. While there was a steady decline in Pfizer’s overall earnings from 2011 to 2014, this is arguably reflective of the decline in Lipitor sales rather than any impact caused by Omnitrope’s performance.[43]

Figure 2. Pfizer worldwide revenues and global Lipitor sales from 2003 to 2015. Data sourced from Pfizer financial reports for financial years 2006 to 2016.

Pfizer’s revenue profile would suggest that the launch of Omnitrope in the global biopharmaceutical market did not significantly impact on Pfizer’s commercial performance and overall, the financial data presented appears to run contrary to the argument that longer data exclusivity periods are required for innovators to recoup expenses and profit from their investments. However, while the sales profiles of Genotropin, Omnitrope and Lipitor create an inference that revenues generated from the sale of biologics are resistant to biosimilar competition in comparison to how the sale of small-molecule drugs are impacted by generics, the findings presented do not exclude the possibility that other factors may have influenced the trends observed. One such factor could be the measures taken to prevent loss of future revenue to rival competition.

Aside from the financial data presented, it is worth noting that Genotropin is not considered a blockbuster product when compared with Lipitor whose annual sales between 2001 and 2011 represented approximately 25% of Pfizer’s annual worldwide revenues.[44] Prior to the expiry of Lipitor’s patents in 2011, Pfizer implemented many unprecedented pre- and post-patent expiration strategies to protect and extend Lipitor sales to prevent what could have been a very heavy impact on Lipitor sales and Pfizer revenues by generic competition. The strategies implemented involved entering into agreements with generic drug manufacturers to minimize the financial impact of generic competition, such as “pay-for-delay” and “authorized generic” agreements; investing heavily on direct-to-consumer marketing for Lipitor in the years immediately prior to patent expiration; implementing a customer discount program called “Lipitor For You”, which offered benefits to privately insured patients, including the purchase of Lipitor at a copayment price well below the average copayment price for generics; and finally, raising Lipitor’s retail price just prior to patent expiration.[45]

In comparison to Lipitor, Pfizer did not invest heavily to block biosimilar competition to Genotrophin. Ironically, Omnitrope’s major hurdle in gaining marketing authorization in the US was due to delays by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The approval granted to Sandoz in May 2006 marked the culmination of a lengthy filing process which began when Sandoz first filed in July 2003.[46] After the FDA failed to “reach a decision on the approvability of the application because of unresolved scientific and legal issues”[47] in August 2004, Sandoz sued the FDA in 2005 with the aim of compelling them to make a decision. In April 2006, the FDA was ordered by a US federal court to act on Sandoz’s application and decide whether or not to grant marketing approval to Omnitrope. Approval was granted shortly after in May 2006.[48]

The measurers Pfizer had taken to protect Lipitor sales when compared to Genotropin run counter to industry lobbying for increases in the data exclusivity period for biologics. Rather, it highlights that biosimilars may not actually pose a great threat to the biologics they imitate. However, the impact of biosimilars on originator biologics are likely to involve other factors. At present, there is insufficient data available to determine how biosimilars would impact on the sales of blockbuster biologics and the profits earned by their manufacturers in the long term since most have only recently fallen of the patent cliff.

On 6 March 2015, the FDA announced the approval of Zarxio (filgrastim-sndz), the first biosimilar to be approved in the US. Manufactured by Novartis/Sandoz, Zarxio is the biosimilar of Amgen’s blockbuster biologic, Neupogen.[49] With Zarxio’s sales launch in September 2015,[50] whether a blockbuster biologic will follow in the footsteps of Lipitor or Genotropin in terms of sales will become evident in the near future as more biosimilars hit the market.

The profitability of a product determines whether or not an investment will be or continue to be made.[51] As such, manufacturers of originator biologics want assurance that they will be able to recover their investment and reap profits sufficient to justify continuance of their research and development efforts.[52] The grant of a time-limited monopoly rewards an originator for the risk and expense associated with bringing a product to market by affording inventors an extra-competitive advantage over their competitors.[53]

One of the main arguments propounded by those pushing for greater data exclusivity periods in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries is the claim that shortening of the exclusivity period will have severe negative effects on innovation. This point of contention was relied upon by Amgen in their submissions to the Pharmaceutical Patents Review Report 2013 when they stated that data protection was important for biologics because the complexity in their size and structure make it easy for patents to be “designed around”.[54] As such, Amgen anticipated that insufficient data exclusivity protections will place the development of innovative biologics at risk of imitation by rival companies long before originators have had the opportunity to recover research and development costs or gained profitable returns on their investment.[55] However, based on the following two lines of independent evidence, the argument that innovation is negatively affected by data exclusivity periods that are less than 12 years is revealed to be weakly supported.

Using financial data sourced from the annual reports of various major pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer, Amgen, AbbVie, and Johnson & Johnson,[56] a survey of research and development expenditure from 2003 to 2015 revealed consistent investment, as is the case for Pfizer, or increased investment over a 5 to 12 year period (Figure 3). This is despite patents having ended or nearing the end of their terms of protection.[57] Research and development expenditure from Amgen and Johnson & Johnson have gradually increased even though the 12 year data exclusivity protections provided by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act were only enacted in 2010. Further, in 2010, the financial year following the expiry of Pfizer’s patent over Genotropin, rather than decreasing research and development expenditure, Pfizer increased its investment into research and development by more than $US1.6 billion compared to the previous financial year.

The implications of these findings refute the claim that investment into innovation will diminish with data exclusivity periods that are less than 12 years. Rather, the findings revealed by the financial data emphasizes the importance of research and development, and that investment into improving and innovating current and future medicines are, to an extent, shielded from the company’s financial pressures from rivals.

Another indicator of innovation can be gleaned from the number of patent applications filed and granted by various patent authorities including the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), European Patent Office (EPO), and IP Australia (IPA).

The USPTO is a US federal agency responsible for issuing patents and registering trademarks. The Patent Technology Monitoring Team conducts a series of statistical analyses of trends emerging from the various patent applications filed and granted by the USPTO to domestic and foreign entities.[58]

|

USPTO Utility Applications Filed

|

Year

|

||

|

2005

|

2010

|

2014

|

|

|

USA

|

207,867

|

241,977

|

285,096

|

|

Foreign

|

182,866

|

248,249

|

293,706

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

USPTO Utility Applications Granted

|

2005

|

2010

|

2014

|

|

USA

|

74,637

|

107,791

|

140,969

|

|

Foreign

|

69,169

|

111,823

|

157,438

|

Table 1. Utility Applications Filed to the USPTO from 2005 to 2014.[59]

Based on the data available for utility applications filed and granted in the US between 2005 to 2014, a clear increase is observed in the number of patent applications filed and granted over the 9 year period (Table 1). Further, the ratio of applications of US to foreign origin is approximately 1:1, with filing averages of 50.61% for US applications and 49.39% for foreign applications while patent grants averaged at 49.2% for US applications and 50.8% for foreign applications.

|

USPTO Patent Grants for Technology Classes 424 & 514

|

Year

|

||

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

|

|

USA

|

2,603

|

4,188

|

7,024

|

|

Foreign

|

1,866

|

3,321

|

5,669

|

Table 2. Patents Granted by Technology Class by the USPTO from 2005 to 2015.[60]

A further breakdown of the patent applications filed and granted based on technology class revealed that for patents relating to biotechnology and biopharmaceuticals, which fall under Patent Technology Classes 424 and 514,[61] the number of patents granted between 2005 to 2015 have markedly increased (Table 2). In the US, the number of patents granted since 2005 has increased by 270%. Similarly, the number of patents granted to foreign applications has increased by 300% since 2005.

The EPO is the main patent repository and grant agency in Europe. Similar to the USPTO, the EPO carries out analyses of the data gathered from patent application filings.[62] The trends revealed by the applications filed and granted by the EPO from 2006 to 2015 by field of technology are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. European Patent Applications Filed by Field of Technology from 2006 to 2015.[63]

|

European Patent Applications by Field of Technology

|

Year

|

||

|

2006

|

2010

|

2015

|

|

|

USA Biotechnology

|

1,690

|

2,862

|

1,915

|

|

Europe + All Foreign Biotechnology

|

3,514

|

4,857

|

4,133

|

Based on the number of applications submitted in the area of biotechnology, the primary classification covering biologics and biosimilar patent applications, there is an overall increase in the number of applications submitted between 2006 and 2015. However, the number of applications submitted to the EPO after 2010 by the US, Europe and all foreign nations has since decreased. This is in contrast to the applications filed to the USPTO, which have been steadily increasing over the same period. It should be noted that while the data sourced from the USPTO in Table 2 combines the biotechnology and biopharmaceuticals patent technology classes, the patents granted for both classes had increased during the periods of decline reported by the EPO.

The overall reduction in patent applications filed to the EPO may be due to external factors as the period of decrease coincides with the European debt crisis, in particular, the Greek government-debt crisis, which started in late 2009. Historically, patent filings and investment into research, development, and innovation have mirrored the trends in a country’s Gross Domestic Product.[64] In a study examining the effects of the international crisis on innovation, it was found that the international debt crisis followed by Greece’s looming bankruptcy had negatively affected innovation, where patent filings to the EPO were decreased after 2010. Further deceases in patent filings followed from 2011 to 2013, however, recovery and increase become evident from 2014 when Greece partly regained market access.[65]

IPA is the federal agency in Australia responsible for the issuing of patent grants.[66] As with the USPTO and EPO, IPA has also conducted studies based on the patent applications filed in Australia. A recent patent analytics study on the Australian pharmaceutical industry by the Patent Analytics Hub in September 2015 involved the assessment of Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT)[67] applications filed by Australian applicants.[68] In regards to the biotechnology/biopharmaceutical sector, 43% (1,183 applications) of PCT applications filed by applicants in Australia related to biologics. Moreover, of those PCT patents filed, 72% related to the development of new biologics. In comparison, an average of 29% of PCT applications filed by foreign applicants related to biologics. However, it should be noted that of the 29% of PCT applications filed by foreign applicants, foreign corporations were the main contributors. Of the number of PCT applications filed by foreign corporations, 43% (232 applications) were classed under the biologics category.[69]

When this information is considered in relation to the study’s analysis of the number of biologics patent application filings over time, it is revealed that the rate of PCT applications filed for new biologics has remained steady since 2004, averaging at approximately 50 applications from 2004 to 2012. Furthermore, the study reported that the trends observed for Australian applications were mirrored by applications filed from the rest of the world.[70] Accordingly, the results yielded by the study imply that investment and innovation into new biologics in Australia – by both Australian and foreign applicants – have remained relatively steady despite the Therapeutic Goods Act providing only 5 years of data exclusivity for biologics, and despite ongoing changes to regulatory regimes for biologics and biosimilars.

In summary, the data sourced from the USPTO, EPO and IPA demonstrate an overall increase in patent applications filed since 2005. This is in spite of the decrease in patent filings to the EPO after 2010. In particular, data from the USPTO reveal that the number of patent grants for US and foreign applicants have also increased. The Australian study conducted by IPA is significant in that it demonstrates that even with a shorter data exclusivity period, there is a strong emphasis on the development of new biologics. Accordingly, on the basis of the information sourced from the three major patent offices, the argument that longer data exclusivity periods are required to stimulate innovation in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries is weakly justified.

There is a school of thought that suggests that extended monopolies can threaten innovation. Moves to extend the term of exclusivity have been suggested by some to slow the pace of innovation by hampering the discovery of new or improved biologics by restricting access to prior knowledge.[71] In particular, Kenneth Arrow, a Nobel Memorial Prize awardee in economics, is adamant that monopolies do not drive innovation arguing that “the incentive to invent is less under monopolistic than under competitive conditions”.[72] According to this argument, it can be presupposed that, rather than threatening the will to innovate, biosimilars may actually encourage innovation and the discovery of new biologics. This is plausible when consideration is had for the pharmaceutical sector where intense competition from low cost generic drugs has, for many years, encouraged and stimulated innovation into new and improved drugs.[73] Moreover, the emergence of companies branching off from existing major pharmaceutical corporations to focus exclusively on pharmaceuticals and/or biopharmaceuticals, is good evidence of this. For instance, Novartis’ subsidiary, Sandoz, is one of the world’s largest generic drug companies with a strong emphasis on biosimilar development. Likewise, AbbVie, which was formed by Abbott Laboratories to function as a research-based pharmaceutical manufacturer, effectively separated from Abbott Laboratories on 2 January 2013.[74]

Research has shown that extending data exclusivity provides only limited rather than substantial benefits for originators. Where longer periods of data exclusivity have been made available, only a few top-selling small molecule drugs have gained further marketing monopolies. This is all the more so when patent terms have been extended. By contrast, drugs that have benefited from longer data exclusivity periods were those that did not receive extended patent terms or those that experienced exceptionally long research and development processes.[75] Moreover, a research study conducted in 2013 investigating whether pharmaceutical companies invest more in countries with data exclusivity found that data protection does not appear to have any major impact on the levels of pharmaceutical investment in a country.[76]

While it remains to be seen if the same will hold true for biologics, the evidence presented in this thesis suggests that it probably will. It can be seen from the financial data from several major pharmaceutical companies that there have been substantial gains in overall company profits and importantly, there has been no significant impact on biologic sales from biosimilar entry into the market. Further, investment into research and development have increased overall in the past 12 years, refuting claims of erosion into the innovation and development of new biologics. In support of this, patent application filings and grants pertaining to biopharmaceutical products including biologics over the past 10 years have continued to increase in the US, Europe and Australia. Specifically, the number of PCT applications in relation to new biologics filed at the Australia patent office at IPA has remained constant since 2004. Accordingly, the evidence and research argues against the need for an increase in the current data exclusivity periods.

The 12 year data protection period for biologics ultimately enacted by the US Congress in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was provided in Bill H.R. 3590 (111th Congress, 2009).[77] Much like the protracted negotiations, which delayed the TPP in regards to the issue of biologics, adoption of the 12 year data exclusivity period was subject to controversy.

In an earlier alternative Bill, which was passed over in favour of H.R. 3590, Representative Waxman and other sponsors of H.R. 1427 advocated for a 5 year data exclusivity period, arguing that the 5 year period provided in the Hatch-Waxman Act had correlated with robust innovation in the pharmaceutical industry in relation to small-molecule drugs. Representative Waxman and the co-sponsors of H.R. 1427 based their argument on the assumption that there was no difference between traditional small-molecule drugs and biologics in terms of research and development expenditure and timelines. On that basis, they concluded that there would be no requirement for longer data exclusivity periods for biologics.[78]

The view of Representative Waxman and the co-sponsors of H.R. 1427 contrasts with findings from a report issued by the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in June 2009, which examined the potential impact that follow-on biologics – such as biosimilars – would have on the price of biologics in comparison to the impact that generic small-molecule drugs had on their brand name counterparts.[79] Notably, the report found on multiple grounds that competition between follow-on biologics and the originator biologics that they are based on was unlikely to be similar to the competition between generic and brand-name small-molecule drugs. The FTC report further found that a 12 to 14 year market exclusivity period was not necessary and that the period was too long to spur innovation, particularly since manufacturers of originator biologics will retain substantial market share after the entry of follow-on biologics into the market. Moreover, the report concluded that there were adequate incentives provided from patents and market-based pricing.[80] The findings of the FTC report are consistent with the differing trends in product sales revenue and company profits observed between Genotropin and Lipitor after their respective biosimilar and generic competition entered the market and accordingly, support the conclusions reached. The findings from the FTC report may have resonated with the US government. Since 2012, the Obama Administration’s budget proposals have included a 7 year market exclusivity period devised by the government as “a generous compromise between what the FTC research has concluded and what the pharmaceutical industry has advocated”. To date, the proposal for a 7 year data exclusivity period for biologics has not been implemented.[81]

In 2013, a report published by the Pharmaceutical Patents Review Panel found, among other things, that there was insufficient evidence at present to support an increase in the data exclusivity period beyond the current 5 year term for biologics in Australia. This conclusion was reached by the Panel with a qualification that the regulatory environment and market for biologics and biosimilars are continuing to evolve and that, while 5 years at present was adequate, the situation should be reviewed in future when additional data becomes available and further market experience can paint a clearer picture and understanding of the relevant issues.[82]

This qualification by the Panel is practical and is reflected in the TPP provision for data exclusivity for biologics. While the agreement was ultimately a compromise, allowing a maximum of 8 years of data exclusivity and the flexibility of members to agree to fewer than 8 years is a prudent measure that takes into consideration that biologics and biosimilars are emerging markets. It also provides the option for member countries like Australia, that have ratified the TPP on fewer than the maximum number of years, to increase their data exclusivity periods when the domestic regulatory landscape requires.

Biologics are an important and innovative development in pharmaceuticals with the potential to bring substantial health benefits to the public. In addition to patents, data exclusivity provides an additional layer of protection for biologics by allowing a time-limited market exclusivity for originators as an incentive to invest, particularly in cases where a patent can be circumvented. However, lobbying by the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries for governments to increase the data exclusivity periods in countries which traditionally have a fewer number of years, as illustrated by the TPP negotiations, moves the rationale of data exclusivity being employed as an incentive to drive research, development and innovation to a tool to extend market monopoly. While at present the evidence is not strong enough to justify extending periods of data exclusivity, there is no denying that biologics and biosimilars are an emerging market and that, some time in future, the regulatory landscape might progress to a stage where longer terms will be required to meet teleological goals. The TPP provides a good example of an agreement in which the terms of data exclusivity for biologics can be resolved, but with scope for future development.

[1] Kristina Lybecker, ‘Essay: When Patents Aren't Enough: Why Biologics Necessitate Date Exclusivity Protection’ (2014) 40 William Mitchell Law Review 1427, 1429-1431.

[2] Ibid 1432; Business Roundtable, The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement: An Opportunity for America (2013) <http://businessroundtable.org/studies-reports/downloads/TPP_Summary_Oct_2013.pdf> Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Summary of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (6 October 2015) <http://dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/tpp/outcomes-documents/Pages/summary-of-the-tpp-agreement.aspx> the 12 member countries included United States, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Brunei, Chile, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Mexico, Singapore, Peru.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) s25A.

[5] Adam Denley and Sarah Hennebry, Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement on Term of Data Exclusivity for Biological Pharmaceuticals, not Patent Term (6 October 2015) <http://www.freehillspatents.com/resource?id=387> .

[6] Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Outcomes Biologics (6 October 2015) <http://dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/tpp/outcomes-documents/Pages/outcomes-biologics.aspx> .

[7] Dan Stanton, TPP: Five Years Data Protection for Biologics in US-Asia Trade Deal (5 October 2015) <http://www.biopharma-reporter.com/Markets-Regulations/TPP-Five-years-data-protection-for-biologics-in-US-Asia-trade-deal> .

[8] Tony Harris, Dianne Nicol and Nicolas Gruen, ‘Pharmaceutical Patents Review Report’ (Canberra, 30 May 2013) 170; Josef Drexl and Nari Lee (eds), Pharmaceutical Innovation, Competition and Patent Law - A Trilateral Perspective (Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2014) 133.

[9] IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, Assessing biosimilar uptake and competition in European markets (October 2014) <https://www.imshealth.com/files/web/IMSH%20Institute/Healthcare%20Briefs/Assessing_biosimilar_uptake_and_competition_in_European_markets.pdf>.

[10] See the new report from Transparency Market Research entitled ‘Biological Drugs Market - Global Industry Analysis, Size, Share, Growth, Trends and Forecast 2014 – 2020’; See also Transparency Market Research, Global Biological Drugs Market to be worth US$287.1 bn by 2020 (10 November 2015) <http://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/pressrelease/biological-drugs-industry.htm> .

[11] Evaluate, ‘EvaluatePharma® World Preview 2015, Outlook to 2020’ (8th Edition, June 2015) 36.

[12] Harris, above n 8; Drexl and Lee, above n 8; Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Online, US$67 billion worth of biosimilar patents expiring before 2020 (20 January 2014) <http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/US-67-billion-worth-of-biosimilar-patents-expiring-before-2020> Alan Sheppard and Antonio Iervolino, ‘Biosimilars: about to leap?’ (Paper presented at 10th EGA International Symposium on Biosimilar Medicines, London UK, 19 April 2012); Ronny Gal, ‘Biosimilars: Reviewing US Law and US/EU Patents. Bottom Up Model Suggests 12 Products and $7-$8B Market by 2020’ (Bernstein Research, 26 May 2011).

[13] Erwin Blackstone and Joseph Fuhr Jr, ‘The Economics of Biosimilars’ (2013) 6 American Health & Drug Benefits 469.

[14] IMS Health, Shaping the biosimilars opportunity: a global perspective on the evolving biosimilars landscape (December 2011) <http://weinberggroup.com/pdfs/Shaping_the_biosimiliars_opportunity_A_global_perspective_on_the_evolving_biosimiliars_landscape.pdf> .

[15] Ibid; Michael Gibney, ‘Google Invests in Oral Drug Delivery for Insulin, Other Biologics’ on Fierce Drug Delivery (3 September 2013) <http://www.fiercedrugdelivery.com/story/google-invests-oral-drug-delivery-insulin-other-biologics/2013-09-03> .

[16] Lybecker, above n1, 1431-1433.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid; Joseph DiMasi and Henry Grabowski, ‘The Costs of Biopharmaceutical R&D: Is Biotech Different?’ (2007) 28 Managerial and Decision Economics 469, 476; Henry Grabowski, Genia Long and Richard Mortimer, ‘From the Analyst’s Couch: Data Exclusivity for Biologics’ (2011) 10 Nature Reviews: Drug Discovery 15-25.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Harris, above n 8; Lybecker, above n 1.

[22] Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) s 25A.

[23] Donna Gitter, ‘Biopharmaceuticals Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Determining the Appropriate Market and Data Exclusivity Periods’ (2013) 21 Texas Intellectual Property Law Journal 213, 231.

[24] Ibid; the Hatch-Waxman Act is the informal reference to the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act 1984.

[25] Blackstone and Fuhr Jr, above n 13.

[26] Gerald Mossinghoff, ‘Overview of the Hatch-Waxman Act and Its Impact on the Drug Development Process’ (1999) 54 Food and Drug Law Journal 187.

[27] Yaniv Heled, ‘Parents vs Statutory Exclusivities in Biological Pharmaceuticals – Do We Really Need Both?’ (2012) 18 Michigan Telecommunications and Technology Law Review 419, <http://www.mttlr.org/voleighteen/heled.pdf> .

[28] Ibid.

[29] Blackstone and Fuhr Jr, above n 13, 470.

[30] Health Canada, Publication of Updates to Guidance Document: Data Protection Under C.08.004.1 of the Food and Drug Regulations 6 (2010) <http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodpharma/applic-demande/guide-ld/data_donnees_protection-eng.php#a26)> .

[31] Donna Gitter, ‘Informed by the European Union Experience: What the United States Can Anticipate and Learn from the European Union's Regulatory Approach to Biosimilars’ (2011) 41 Seton Hall Law Review 559, 566.

[32] Select USA, The Pharmaceutical and Biotech Industries in the United States <http://selectusa.commerce.gov/industry-snapshots/pharmaceutical-and-biotech-industries-united-states.html> .

[33] Duff Wilson, ‘Drug Firms Face Billions in Losses in ’11 as Patents End’ on New York Times (A1, 6 March 2011) <www.nytimes.com/2011/03/07/business/07drug.html?pagewanted=all>; Melly Alazraki, ‘The 10 Biggest-Selling Drugs that are About to Lose their Patent’ on Daily Finance (27 February 2011) <www.dailyfinance.com/2011/02/27/top-selling-drugs-are-about-to-lose-patent-protection-ready/>.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Anup Roy, Biosimilars: The New Threats on the Block (28 February 2016) <http://dufs.co.uk/market-report/biosimilars-the-new-threats-on-the-block/> .

[36] Leigh Purvisa and Stephen Schondelmeyer, ‘Rx Price Watch Case Study: Efforts to Reduce the Impact of Generic Competition for Lipitor’ (AARP Public Policy Institute, PRIME Institute, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 13 June 2013) <http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2015/lipitor-final-report-AARP-ppi-health-june-13.pdf> .

[37] Roy, above n 35.

[38] Wood Mackenzie, ‘Omnitrope’s US Appro Sets No Precedents for Biogenerics’ on The Pharma Letter (19 June 2006) <http://www.thepharmaletter.com/article/omnitrope-s-us-appro-sets-no-precedents-for-biogenerics-says-wood-mackenzie> .

[39] Pfizer Inc, ‘10-K forms on United States Securities and Exchange Commission (2006-2016)’ <http://www.sec.gov/cgi-bin/browse-edgar?action=getcompany & CIK=0000078003 & type=10-k & dateb= & owner=include & count=40> Sandoz, Facts and Figures 2013 <http://metronidazol.info/cs/www.sandoz.com-v4/assets/media/shared/documents/Fact_Figures_2013.pdf>

Newsletter, 'Sandoz’ Biosimilar Sales Top US$100mn in 2009’ Generics Bulletin (1 February 2010) <http://www.sandoz.com/cs/www.sandoz.com-v4/assets/media/shared/documents/sandoz_in_the_media/Gx_Bulletin_2010.02.01_p.01.pdf> Data for Genotropin sales was sourced from Pfizer financial reports for financial years 2006 to 2016. Omnitrope sales figures were sourced from Sandoz 2013 financial report and 2010 media release. Data for Genotropin sales was sourced from Pfizer financial reports for financial years 2006 to 2016. Omnitrope sales figures were sourced from Sandoz 2013 financial report and 2010 media release.

[40] The wholesale acquisition cost is a manufacturers’ estimation of the list price for a drug to be paid by a wholesaler, distributor and direct purchaser. Generally, the wholesale acquisition cost does not include any discounts, rebates, allowances or other price concessions offered by the manufacturer.

[41] Henry Grabowski, Genia Long, and Richard Mortimer, ‘Implementation of the Biosimilar Pathway: Economic and Policy Issues’ (2011) 41 Seton Hall Law Review 511.

[42] Pfizer Inc, above n 39; Sandoz, above n 39; 'Sandoz’ Biosimilar Sales Top US$100mn in 2009’, above n 39.

[43] Pfizer Inc, above n 39.

[44] Purvisa, above n 36.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Mackenzie, above n 38.

[47] Sandoz Inc v Leavitt, 427 F. Supp. 2d 29 (DDC 2006), 2.03[A].

[48] Ibid; Paul Saenger, ‘Current Status of Biosimilar Growth Hormone’ on International Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology (29 September 2009) <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2777019/pdf/IJPE2009-370329.pdf> .

[49] David Kroll, ‘FDA Approves First US Biosimilar; Hold Your Breath On Cost Savings’ on Forbes – Pharma and Healthcare (6 March 2015) <http://www.forbes.com/sites/davidkroll/2015/03/06/fda-approves-first-us-biosimilar-zarxio-by-sandoz/#734d248e76c9> .

[50] Ibid.

[51] Lybecker, above n 1.

[52] Heled, above n 27.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Harris, above n 8, 160.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Pfizer Inc, above n 39; Amgen Inc, ‘10-K forms on United States Securities and Exchange Commission (2005-2016)’ <http://www.sec.gov/cgi-bin/browse-edgar?action=getcompany & CIK=0000318154 & type=10-k & dateb= & owner=exclude & count=40> AbbVie Inc, ‘10-K forms on United States Securities and Exchange Commission (2013-2016)’ <http://www.sec.gov/cgi-bin/browse-edgar?action=getcompany & CIK=0001551152 & type=10-k & dateb= & owner=exclude & count=40> Johnson & Johnson, ‘10-K forms on United States Securities and Exchange Commission (2007-2016)’ <http://www.sec.gov/cgi-bin/browse-edgar?action=getcompany & CIK=0000200406 & type=10-k & dateb= & owner=exclude & count=40> .

[57] For example, Amgen’s patents over its blockbuster biologic, Neupogen in the EU and USA have since expired; AbbVie’s patent over Humira is due to expire in December 2016 in the USA and October 2018 in the EU; and Johnson & Johnson’s patent over Remicade have since expired in the EU and is due to expire in September 2018 in the USA; Generics and Biosimilars Initiative Online, above n 12.

[58] Patent Technology Monitoring Team (PTMT), ‘Calendar Year Patent Statistics (January 1 to December 31) General Patent Statistics Reports Available For Viewing’ on United States Patent and Trademark Office <http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/reports.htm> .

[59] Patent Technology Monitoring Team (PTMT), ‘U.S. Patent Statistics Chart

Calendar Years 1963 – 2015’ on United States Patent and Trademark Office <http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/us_stat.htm> .

[60] Patent Technology Monitoring Team (PTMT), ‘Patent Counts By Class By Year January 1977 – December 2015’ on United States Patent and Trademark Office <http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/cbcby.htm#Desc> .

[61] United States Patent and Trademark Office <http://www.uspto.gov/web/patents/classification/uspc514/defs514.htm> : Class 514 is a subclass of Class 424. They differ in scope as to the procedure used for cross-referencing. Class 514 incorporates all Class 424 definitions and rules as to subject matter.

[62] European Patent Office, Statistics <https://www.epo.org/about-us/annual-reports-statistics/statistics.html>.

[63] Statistics, ‘European Patent Applications 2006-2015 per Field of Technology’ European Patent Office <https://www.epo.org/about-us/annual-reports-statistics/statistics.html>.

[64] Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Investing in Innovation for Long-Term Growth (June 2009) <https://www.oecd.org/sti/42983414.pdf>.

[65] Maria Markatou, ‘Has the Economic Crisis Affected the Production of Innovation in Greece?: Evidence from Patents’ on (2014) on The South and East European Development Center (SEED) <http://www.seedcenter.gr/conferences/Crisis2014/papers/Markatou_has%20the%20economic%20crisis%20affected%20the%20production%20of%20innovation%20in%20greece%20evidence%20from%20patents.pdf> .

[66] IP Australia, Patents <https://www.ipaustralia.gov.au/patents>.

[67] PCT is an abbreviation for the Patent Cooperation Treaty, an international patent law treaty that was concluded in 1970. The treaty sets out a unified procedure for filing patent applications in each of its contracting states. Patent applications filed under the treaty is often referred to as a PCT application.

[68] IP Australia, A Patent Analytics Study on the Australian Pharmaceutical Industry (September 2015) <https://www.ipaustralia.gov.au/sites/g/files/net856/f/pharma_report_2016.pdf>.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Burcu Kilic and Courtney Pine, ‘Inside Views: Decision Time On Biologics

Exclusivity: Eight Years Is No Compromise’ on Intellectual Property Watch (27 July 2015) <http://www.ip-watch.org/2015/07/27/decision-time-on-biologics-exclusivity-eight-years-is-no-compromise/#_ftn5> .

[72] Kenneth Arrow, ‘Economic Welfare and the Allocation of Resources for Invention’ (Rand Corporation Working Paper P-1856-RC, 15 December 1959).

[73] David Dudzinski and Aaron Kesselheim, ‘Scientific and legal viability of follow-on protein drugs’ (2008) 358 New England Journal of Medicine 843–849.

[74] Inelegant Investor, ‘Abbott and AbbVie- Spinoff Complete, Companies Begin To Walk Their Own Paths’ on Stock Spinoffs (4 January 2013) <http://www.stockspinoffs.com/2013/01/04/abbott-and-abbvie-spinoff-complete-companies-begin-to-walk-their-own-paths/> .

[75] IMS Health, Data Exclusivity – The Generics Market’s Third Hurdle (November 2001).

[76] Mike Palmedo, ‘Do Pharmaceutical Firms Invest More Heavily in Countries with Data Exclusivity?’ Currents: International Trade Law Journal (Summer, 16 May 2013) <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2259797> .

[77] Maxwell Morgan, ‘Regulation of Innovation Under Follow-On Biologics Legislation: FDA Exclusivity as an Efficient Incentive Mechanism’ (2010) 11 Columbia Science and Technology Law Review 93, 96-97.

[78] Ibid 96-99; United States House Committee on Energy and Commerce, ‘Q's and A's on the “Promoting Innovation and Access to Life-Saving Medicine Act”’ (Press Release, 11 March 2009).

[79] Federal Trade Commission, Emerging Health Issues: Follow-on Biologic Drug Competition Report (10 June 2009) <http://www.ftc.gov/os/2009/06/P083901biologicsreport.pdf> .

[80] Ibid.

[81] Ibid; A letter from Nancy-Ann DeParle, Director of the Office of Health Reform, and Peter Orszag, Director, of the Office of Management and Budget, to Henry Waxman, Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee (24 June 2009).

[82] Harris, above n 8, 181.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJlStuS/2016/7.html