|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal Student Series |

HERE COMES THE SUN: REMOVING THE BARRIERS THAT SHADOW THE UPTAKE OF ROOFTOP SOLAR IN AUSTRALIAN APARTMENTS

GEORGIA PICK

I INTRODUCTION

Distributed energy resources (‘DERs’) – smaller generation units located near the point of consumption – are challenging the traditional, centralised model of electricity generation in Australia.[1] The proportion of consumers within the National Electricity Market that used rooftop solar photovoltaic (‘PV’) units increased from 0.2 to 12 per cent between 2007-8 and 2017-18.[2] Within the residential sector, there were just under 155 000 solar PV installations in 2017, representing a 25 per cent increase from 2016.[3] This increase in installations corresponds to nation-wide increases in retail electricity prices in 2017.[4] For example, residential consumers of electricity experienced a 35 per cent increase in their electricity bills between 2007-8 and 2017-18.[5] In addition to increases in energy prices, the growth in the uptake of solar PV has been driven by decreases in the cost of solar PV[6] and batteries used for energy storage.[7]

However, the growth in solar PV uptake is not being experienced in apartments. In 2016, 20 per cent of detached houses had solar PV compared to 1 per cent of apartments.[8] This is not commensurate with the proportion of the population living in detached houses and apartments; 73 and 13 per cent respectively.[9] Since the ratio of apartments to occupied houses is growing,[10] the underrepresentation of solar PV in apartments will become increasingly pronounced.

Notwithstanding this, the use of DERs like solar PV in multi-owned properties has not been widely researched (relative to that in detached houses).[11] This essay intends to contribute to the growing, multidisciplinary body of literature on the use of solar panels in multi-owned properties. Part II will briefly explain why the underrepresentation of solar PV in apartments is problematic. Part III will describe how apartment residents can access solar PV, with a focus on models for supplying electricity generated by solar PV in apartments (as opposed to offsite options).[12] Part IV will discuss the barriers to the uptake of solar PV in apartments: strata title law and governance issues (specifically, the difficulty of passing the special resolutions needed to install solar PV systems), and the regulatory burden associated with complying with energy law. This essay will conclude with a discussion of the ways that these barriers can be mitigated (Part V). This essay argues that strata title legislation should be amended to lower the voting threshold required to install solar PV systems, although the business case for the making the investment must be simultaneously enhanced. Further, energy law compliance should not be made easier because this could lower consumer protection. Novel supply arrangements and developers installing solar systems throughout construction can avoid the above issues and should be investigated further. However, there are consumer protection issues associated with both options that need to be addressed.

II THE UNDERREPRESENTATION OF SOLAR PV IN APARTMENTS: A MISSED OPPORTUNITY

The underrepresentation of solar PV in apartments is not ideal because the increased use of solar PV can reduce greenhouse gas emissions. For example, the Orchards is a master planned estate that will be built in Sydney and comprise 1300 units and a 1GW solar PV system.[13] It is estimated that the resulting reduction in carbon emissions will equate to planting approximately 15 000 trees per year.[14] Yet perhaps more persuasively, generating electricity from solar PV can deliver significant cost-savings for residents. In their study based in Canada, Hachem, Athienitis and Fazio found that apartments of three storeys could satisfy approximately 96 per cent of total energy demand, ‘if the roof design is optimised for solar energy generation’ and the building is energy efficient.[15] Since apartment blocks with three storeys or less constitute 61 per cent of apartments in Australia,[16] solar PV has the potential to power a significant proportion of apartment buildings in Australia and therefore enable residents to experience significant savings on their electricity bills. For example, Stucco is a three-storey student housing co-operative in Sydney with a 30kW solar system and a 42.3kW battery storage system.[17] There are currently 40 residents in the 8-unit complex, and the solar system supplies 80 per cent of the building’s energy demand.[18] Over 2017, residents’ electricity bills reduced by approximately 55 per cent.[19] Although the extent to which solar PV can cover the energy demand of an apartment decreases as the number of storeys increases,[20] significant cost-savings can still be realised in high-rise apartments. For example, the new Ascot Green complex in Brisbane contains a nine-storey apartment building with a solar system that will, it is estimated, reduce residents’ electricity bills by up to 70 per cent.[21]

The opportunity that solar PV brings in allowing residents to reduce their electricity bills should not be overlooked, particularly in light of rising electricity bills (see Part I) which is of concern to residents. For example, in January 2018, 83 per cent of CHOICE Consumer Pulse survey respondents stated that they were at least concerned about their electricity bill.[22] Moreover, the overwhelming consensus is that the principal reason that households decide to install solar PV is to reduce their electricity bills.[23] There is nothing to suggest that apartment residents would not be similarly motivated to reduce their electricity bills.

III HOW APARTMENT RESIDENTS CAN ACCESS SOLAR PV

Having established that the underrepresentation of solar PV in apartments is not ideal, this Part will describe the most practical ways to distribute solar energy in apartments. This is important to understand the barriers to the uptake of solar PV in apartments, and to ultimately assess how these barriers can be mitigated.

A Solar PV Purchased by the Owners Corporation

First, the owners of an apartment – collectively known as the Owners Corporation (‘OC’)[24] or Body Corporate[25] under strata title legislation – can purchase a rooftop solar system through its own funding or debt financing.[26] The simplest model would be to use the electricity generated from the system for common property areas[27] – any part of the building or land that falls outside an individual strata lot and is collectively owned by the OC.[28] This is the simplest model because it requires minimal additional cabling and meters and it does not require an embedded network (see below).[29] Although common property energy demand can be quite small in low-rise apartments, it can be substantial in medium- and high-rise apartments.[30] For example, 3-5 Freeman Road in Chatswood, Sydney is a medium-rise apartment building that before adopting sustainable retrofits had common area electricity costs totalling $22 800 per annum.[31] Further, although common property energy demand is likely to peak in the evening, it remains fairly constant throughout the daytime when solar energy production is highest.[32]

However, if an OC wishes to invest in solar PV it may be beneficial for it to also sell electricity produced from the system to residents. This could be for several reasons. The OC may want to allow residents to individually experience cost-savings. But more likely, the output of the system may exceed the common area energy demand of the building (which is more likely to be the case for low-rise apartments).[33] The OC could of course sell the excess back to the grid, but it has a strong financial case for using as much of the electricity generated as possible since feed-in tariffs – the rate received in exchange for feeding electricity into the grid – have significantly decreased.[34] Further, they are expected to remain low because it is no longer necessary for the government to heavily subsidise solar PV since uptake has generally increased.[35] Instead, if the OC sells the electricity to residents, the profit it makes can be used to pay off the cost of the solar system.

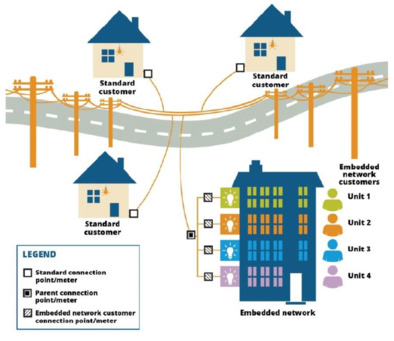

If the OC owns the solar system, the conventional way to distribute and sell

electricity is via an embedded network (see Diagram 1).

Within an apartment

block, electricity is typically provided by an energy retailer to lots

individually; each has a separate meter

connecting it to the grid and pays their

electricity bill to the

retailer.[36] In contrast, an

embedded network is a private electricity network connected to the

grid,[37] which involves a single

parent connection from the building to the grid, with sub-metering for

individual lots and common

areas.[38] Further, residents pay

their electricity bill to the OC instead of an energy retailer, for both solar

energy and electricity purchased

by the OC from the

grid.[39] An example of the use of

an embedded network to distribute solar energy is the WGV Gen Y Demonstration

Housing project in White Gum

Valley,

Perth.[40] The development has three

interlocking low-rise apartments[41]

with rooftop solar PV and battery

storage.[42] Similar arrangements

have been adopted in other

jurisdictions.[43]

Diagram 1: Example of an Embedded Network[44]

B Solar PV Financed through Third-Party Provider

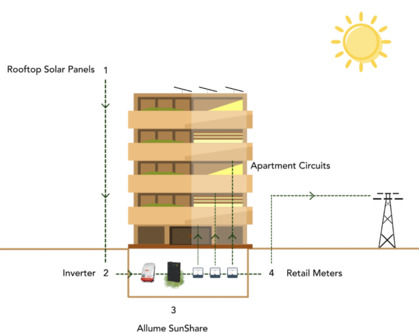

Alternatively, the OC can avoid purchasing the PV system outright by either entering into a lease or a Power Purchase Agreement (‘PPA’) with a third-party renewable energy provider. The first option involves the OC leasing the roof space to the provider to install the system (which it owns and operates for an agreed period) in exchange for the OC making periodic lease payments irrespective of electricity consumption.[45] The second option, which globally is more common and is well-established in Europe and the United States,[46] involves the OC allowing the provider to use the roof space to install a system and sell all electricity generated to the OC at an agreed price.[47] However, it has yet to be widely used in Australia. For example, approximately 103 providers offered PPAs across Queensland, South Australia, NSW and the ACT in June 2016.[48] Notwithstanding this, a company called Allume Energy (‘Allume’) is trying to fill this gap in the market by using a novel arrangement. Allume finances the installation of solar PV in apartments and sells the electricity produced to residents and the OC for common property use.[49] The OC must agree to a roof rental agreement for a term of 10 years, after which the OC can renew the agreement, purchase the system at a discounted rate, or pay Allume to remove the system.[50] Further, Allume enters into a PPA with the OC and residents who choose to opt in to purchasing solar energy at a fixed rate less than the retail electricity price.[51] Allume is able to distribute solar energy in proportion to residents’ usage at a given point in time without an embedded network by using its own technology, Allume SunShare (see Diagram 2).[52] This allows solar energy to be shared from ‘behind the meter’ – that is, by using the building’s existing metering system.[53]

Diagram 2: Allume SunShare and 'Behind-the-Meter' Solar Sharing

IV BARRIERS TO THE UPTAKE OF SOLAR PV IN APARTMENTS

A Strata Title Legislation and Governance Issues

Strata title is a ‘form of legal ownership of properties which enables a building to be subdivided into “lots”’, with the OC jointly owning the common property (see Part III(A)).[54] Almost all apartments are created under strata title legislation,[55] which govern ‘the day-to-day management of strata schemes’.[56] In order to alter the common property or erect a new structure on the common property, a special resolution of the OC must be passed[57] – that is, where not more than 25 per cent of the value of votes cast at a general meeting are against the resolution.[58]

Therefore, for a solar PV system and/or embedded network to be implemented, the OC would need to pass special resolutions.[59] There are several issues that make it likely that at least 25 per cent of a general meeting would oppose these common property changes. First, if the OC purchases the system itself, it must incur a significant cost. Putting aside the fact that capital and operating costs will vary according to the apartment, a solar PV system can in itself carry a payback period of at least seven years.[60] Further, Roberts et al estimate that installing an embedded network would cost $20 000 plus $400 per unit (which excludes the operating costs of the embedded network and billing residents).[61] Together, these costs make the system prohibitively expensive. This is demonstrated through the fact that it cost $130 000 ($80 000 of which was paid by a grant from the City of Sydney) to retrofit the Stucco complex (see Part II).[62] This was the first apartment to retrospectively install a solar system and embedded network.[63]

Secondly, the issue of split-incentives is particularly palpable in apartments. OCs have little incentive to purchase and install a solar PV system (particularly if common area energy demand is low meaning there is little opportunity for cost-savings on their part), yet residents have much to gain through reduced electricity bills.[64] This issue is exacerbated by the fact that 48 per cent of apartments are owned by investors due to Australia’s taxation system (including the ability to negatively gear property).[65] This is problematic because Rex and Leshinsky’s study suggests that owner-occupants are more likely to support sustainable retrofits to common areas.[66] Further, the split-incentive issue is heightened by the high turnover rate in apartment ownership in Australia.[67]

Fortunately, the upcoming third-party financing arrangements discussed in Part III(B) can mitigate these issues and therefore reduce the likelihood of a solar PV proposal being blocked.[68] The OC would still need to pass a special resolution to enter into the roof rental agreement with Allume,[69] but it is much less likely to be blocked since the OC avoids paying for the system,[70] and operational and maintenance costs like billing (which are paid by Allume).[71] Further, the OC is not required to pay periodic payments (as it would with a solar lease); the roof rental agreement simply grants Allume a licence to use the roof for the purpose of installing the solar PV system.[72] The OC would only have to pay for the cost of using solar energy for common areas (if it wishes to enter into a PPA with Allume) and it is in the OC’s financial interests to do so. Additionally, residents are not locked into their PPA with Allume; they can terminate it if they move out of the apartment.[73] One potential issue is that there does not seem to be any mechanism that guarantees that a minimum number of residents have PPAs with Allume at a given point in time (to maintain the financial viability of the installation).[74] However, given the opportunity for financial gain, it is likely that Allume would have little trouble getting residents to replace those who move out of the apartment.

B Complying with the Two-Tiered Energy Law Regulatory Framework

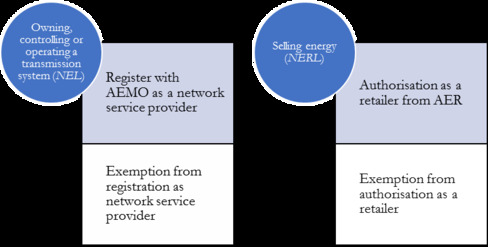

The National Electricity Law (‘NEL’)[75] and the National Electricity Rules (‘NER’)[76] form the legal framework for the National Electricity Market (‘NEM’) – the wholesale electricity market in Australia.[77] The National Energy Retail Law (‘NERL’) regulates the retail supply of electricity to consumers.[78] There are various bodies that operate within this framework. Relevantly, the Australian Energy Market Commission (‘AEMC’) makes the NER[79] and the Australian Energy Regulator (‘AER’) is responsible for enforcing the above legal framework.[80] The NEL and NERL each create two-tiered regulatory frameworks requiring either registration/authorisation or exemption for transmitters and retailers of electricity (see Diagram 3).

Under the NEL, a person must not own, control or operate a transmission system (that is, have wiring connected to the grid and supply electricity to a third person[81]) unless the person is registered by the AEMO as a ‘Network Service Provider’ or are exempt from this requirement under the AER’s guidelines.[82] Third party solar PV providers like Allume are deemed to be exempt.[83] OCs selling electricity to more than 10 residents via an embedded network need to register for an exemption,[84] and gain the explicit informed consent of 85 per cent or less[85] of residents to convert the apartment.[86] For both arrangements, various conditions apply including those relating to metering.[87] However, an OC operating an embedded network must also appoint an Embedded Network Manager[88] (who must, inter alia, maintain information about the metering used[89]). Roberts, Bruce and MacGill argue that the requirement to appoint an ENM can increase the cost of operating an embedded network.[90]

Under the NERL, a person must not sell energy to another for use at premises unless they have a retailer authorisation or are an exempt seller.[91] Third party solar PV providers like Allume[92] will likely only need to register for an exemption, so long as the duration of the PPA is less than 10 years and residents are able to terminate the agreement early.[93] OCs selling electricity to 10 or more residents via an embedded network will also only need to register for an exemption.[94] Although such exemptions are not automatic (in the sense that they require registration), applications are not assessed or approved by the AER.[95] However, if the OC wishes to retrofit the apartment to install an embedded network (as opposed to it being installed by the developer throughout the construction of the apartment), it must apply for an individual exemption.[96] Applications for individual exemptions are assessed by the AER who can impose the conditions it deems necessary.[97]

Diagram 3: The Two-Tiered Regulatory Frameworks for Transmitting and Selling Electricity[98]

From the above, it is not difficult to see that the process of applying for the requisite exemptions could be complex, time-consuming and require costly legal assistance. This is particularly true for retrofitting an apartment with an embedded network.[99] Notably, Roberts et al recall an applicant ‘that required an estimated $130 000 of ... legal assistance to secure retail and NSP exemptions for an embedded network of 6 households’. [100] Ultimately, Benvenuti argues that the regulatory burden associated with establishing an embedded network has meant that residential buildings are rarely converted.[101]

V POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS

A Reforming Strata Title Legislation

Various jurisdictions have sought to mitigate the governance issues unique to multi-owned properties by reducing the voting threshold required to install sustainability infrastructure. This has been done in France, for example, where a simple majority is needed to approve measures that increase the energy efficiency of the building or reduce greenhouse gas emissions.[102] Spain has gone even further in permitting the installation of a renewable energy source with a mere one third of votes.[103] The ACT in Australia has taken a similar stance to France. The Unit Titles (Management Act) 2011 (ACT) permits an OC to approve the installation and financing of ‘sustainability infrastructure’ on the common property by ordinary resolution (a simple majority) rather than special resolution.[104] Yet an OC may only approve such installation or financing if satisfied, after considering various factors (including the direct and indirect costs, and long-term environmental sustainability benefits of the proposed infrastructure[105]) that the long-term benefit of the proposed infrastructure is greater than the cost of installing and maintaining the infrastructure.[106] Since the condition permitting the OC to approve an installation or financing is subjective, a decision refusing a solar PV proposal, for example, could only be contested on the ground that the OC failed to consider one of the prescribed factors.[107] The hope would be that this provision would to some extent prevent the majority voting threshold from being abused, since it directs the OC to consider certain factors.

Although legislation such as this seems to be a good compromise, at least a majority of the OC still needs to be convinced of the financial case for installing a solar system (where it is purchased by the OC) and an embedded network. The most effective way to improve the financial case for this system would be to make environmental upgrade agreements widely available to OCs. These are loans that help cover the capital costs associated with sustainability improvements to buildings, and are repaid through local councils increasing their rates.[108] They therefore mitigate the split-incentive issue discussed in Part IV(A)). Yet since government funding varies in this context, this option cannot be relied on. A simple yet effective alternative could involve OCs using companies like SunTenants, which provide OCs with a structured plan for raising rent to pay off the cost of the system.[109] Although this solution is simple, it deserves attention particularly since Gabriel and Watson found that OCs are concerned that they will not be able to recoup costs through charging higher rent.[110]

B Reforming the Network Service Provider and Selling Exemption Frameworks

1 Using Embedded Networks to Distribute Solar Energy

In response to the issues raised in Part IV(B), various commentators have argued that the network service provider and selling exemption frameworks should be reformed to, in particular, make it easier for OCs to establish embedded networks to distribute solar energy.[111] For example, Robert et al and the Public Interest Advocacy Centre argue that exemptions should be introduced for renewable energy projects using embedded networks that have demonstrable consumer benefits.[112]

Exempt sellers (like embedded network operators) are not subject to the National Energy Customer Framework (‘NECF’),[113] which requires authorised retailers to guarantee certain protections to electricity consumers.[114] Rather, the AER’s network and retail exemption guidelines specify which consumer protections are available to exempt customers.[115] For example, embedded network operators must be a member of the relevant energy ombudsman scheme and comply with this scheme;[116] they cannot impose any condition in a supply contract that ‘unreasonably restricts the ability of a consumer to access an alternative retail market offer’;[117] and must ensure that customers that do not consent to the conversion can be wired out of the embedded network, or if this is impossible, ensure that they will not be financially disadvantaged by the conversion.[118]

Notwithstanding this, the AEMC Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks (‘the AEMC Review’) found that customers within embedded networks receive a lower level of consumer protection than those covered by the NECF.[119] Further, it found that there are ‘significant practical barriers to customers in embedded networks accessing retail market competition’ – that is, it is difficult for them to change their electricity provider if they are unhappy with the provider chosen by the embedded network operator.[120] For example, a member of an OC in an apartment in NSW relayed the following experience to the Review. Upon the formation of the OC, the member was told by the property developer that the OC was required to sign a 10-year fixed-term contract with an electricity provider.[121] The electricity rates provided by the company turned out to be higher than originally stated.[122]

Ultimately, if an OC retrofits an apartment with a solar PV system and an embedded network, it will sell both electricity generated from the system and that which it purchases from the grid. As the AEMC noted, even in arrangements such as this, ‘a range of compliance and consumer issues, common to all embedded networks, can arise’[123] including billing and payment disputes.[124] Hence, access to consumer protections is just as important in embedded networks that are partly used to distribute solar energy as it is in embedded networks that solely distribute grid-supplied energy.[125] This is particularly because consumers argue that combining off-grid and on-grid electricity supply is complex (particularly in relation to ensuring accurate billing).[126] Accordingly, the solution to mitigating the regulatory burden associated with energy law compliance should not involve reducing regulation (which in this context simultaneously reduces consumer protection). Rather, OCs should turn to arrangements that do not require embedded networks (for example, using third-party solar PV providers like Allume, or merely supplying solar energy to common property areas[127]), or rely on developers to establish embedded networks (see Part V(C) below). More generally, therefore, the recommendations made in the AEMC Review that strive to ensure that embedded network customers have access to the same level of consumer protection available to authorised customers should be adopted.[128]

2 Third-Party Solar Providers

Part IV(B) suggests that the regulatory burden associated with third-party providers like Allume installing solar systems and selling electricity to apartment residents is less than that experienced by OCs operating an embedded network. The only relevant condition that third-party providers need to comply with in terms of the sale of electricity is condition 24 which mandates the provision of a notice explaining that the relevant PPA is covered by Australian consumer protection laws.[129] In contrast, various conditions that would typically be imposed on an OC selling electricity via an embedded network do not apply to third-party providers. Most do not seem to be particularly relevant to third-party providers like Allume, or are likely to already be covered by the Australian Consumer Law.[130]

A controversial issue that arises is whether condition 17 – the exempt seller must be a member of the relevant energy ombudsman scheme[131] – should be imposed on third-party providers to give consumers access to their relevant energy ombudsman scheme. According to the Energy and Water Ombudsman Victoria (‘EWOV’), customers should have access if they have an ‘ongoing relationship concerning the supply of energy’ with their retailer.[132] This is because consumer protection agencies (like NSW Fair Trading) and the associated tribunals lack the necessary expertise to deal with these types of disputes.[133] This argument is supported by the fact that the energy ombudsman in Victoria, NSW and South Australia all received a considerable proportion of ‘out of jurisdiction’ energy cases (that they could not investigate) concerning solar installers between 2014 and 2015.[134] For example, the Energy and Water Ombudsman NSW (‘EWON’) regularly receives complaints about misleading statements relating to the reduction in energy bills that will result from solar PV use.[135] On the other hand, the solar industry has argued that increasing consumer protection in the context of solar providers would deter their efforts to contest the electricity retail market, since most are small start-up companies.[136] For example, members of the EWOV are charged per inquiry or complaint, in addition to a ‘small annual membership fee based on customer numbers’.[137] It could also be argued that those who opt in to solar PV systems will tend to be highly informed consumers, and thus Australian Consumer Law will be sufficient to protect them from abuse.[138]

A balance can be struck between these competing considerations. The AER argues that upcoming electricity supply arrangements such as Allume are not identical, and hence the level of consumer protection should vary according to the particular arrangement.[139] This will depend on the complexity of the arrangement and whether the supply in question can be categorised as primary or supplementary.[140] As the EWON acknowledges, while Australian Consumer Law protections enforced by fair trading offices may be sufficient for the purchase and installation of solar systems, an energy-specific resolution scheme is more appropriate for long-term arrangements for the sale of electricity.[141] Although a discussion of how the energy law framework should be specifically reformed to reflect this is beyond the scope of this essay, what is clear is that the retail exemption framework must be sufficiently flexible to ensure that the level of consumer protection (and associated costs of compliance) applied to third-party solar providers can vary according to the nature of the particular arrangement. In the meantime, the consumer issues relating to new electricity supply arrangements should continue to be monitored.[142]

C Developer Installs Solar PV throughout Construction

Given the cost and regulatory burden associated with retrofitting apartments with embedded networks,[143] other arrangements that do not require OCs to establish embedded networks should be seriously considered. However, this does not mean that embedded networks should be abandoned altogether in this context. In addition to allowing solar energy to be distributed to residents (the benefits of which were discussed in Part III(A)), the aggregation of multiple meters behind a single parent meter can allow the OC to purchase grid-supplied electricity at a bulk rate, reducing the electricity bills of residents.[144] This has the flow-on benefit of allowing OCs to charge lower strata levies or rent.[145]

The following question therefore arises: it is easier for developers to finance the implementation of solar systems and embedded networks throughout construction, and then pass on the costs incurred to purchasers of apartment lots?[146] Although developers, like OCs, would have to bear the initial cost, they probably have a greater incentive to make the investment. Like OCs, if the developer decides to retain ownership of the solar system and embedded network, it can benefit from an ongoing revenue stream from the sale of solar energy to residents.[147] Yet unlike OCs, the investment can help developers achieve ‘valuable green ratings or certifications such as National Australian Built Environment Rating System (NABERS) or Green Star’.[148] As the AEMC explains:

Such certifications can assist with negotiations for development approval, can boost the potential profitability of the development by allowing for greater density (e.g. more storeys) in the development, and also boost the development’s marketability to buyers and investors with ‘socially or ethically responsible’ preferences.[149]

Several developers are starting to reap these benefits, however the use of embedded networks to distribute solar energy to apartment residents is not yet commonplace. For example, the Orchards (mentioned in Part II) will contain a solar system and an embedded network, yet solar energy will only be distributed to common property areas.[150] Further, Mirvac has installed a total of 1.1 MW in solar systems in commercial buildings as part of a 12-year trial into the commercial viability of installing solar systems. The systems have been installed by a separate entity called Mirvac Energy, who will partner with an electricity provider to sell energy to the building at the equivalent grid price.[151] This recoups the cost of the PV and generates a long-term income stream, which is crucial for incentivising developers for pay for and install solar systems.[152] Although this arrangement is being trialled, a similar arrangement could be adopted in the apartment sector to strengthen the business case for developers considering installing solar PV systems.

However, there is an outstanding issue that needs to be addressed to encourage developers to establish embedded networks in apartments. As Mirvac’s Residential Sustainability Manager described, embedded networks limit residents’ choice in their electricity provider, resulting in third-line forcing, which has formed an ethical barrier to Mirvac installing embedded networks in its apartments.[153] This is supported by the various stakeholders that made submissions to the AEMC Review describing the impaired ability of embedded network customers to access retail market competition[154] (see Part V(B) above). Therefore, implementing the AEMC’s recommendations that seek to improve embedded network customers’ access to retail competition[155] will be key to easing the concerns of developers and encouraging them to establish solar systems that use embedded networks.

VI CONCLUSION

This essay has demonstrated that there are significant barriers to OCs installing solar systems in apartments and distributing the electricity to residents via an embedded network. First, it is difficult for the OC to pass a special resolution implementing this arrangement due to the costs of installing these systems. Secondly, navigating the two-tiered energy law regulatory framework can be difficult, potentially requiring OCs to spend large sums in legal fees to register for a network service provider exemption and apply for an individual retail exemption. Further, if OCs gain these exemptions, complying with the relevant conditions can be costly.

With respect to the strata title legislation and governance issues, the voting threshold for installing or financing sustainability infrastructure (and necessary utility infrastructure, including an embedded network) should be reduced. However, the underlying financial issues need to simultaneously be addressed. The most effective way to do so without relying on the availability of government funding would be to promote the work of companies like SunTenants within the apartment community, which can provide OCs with structured plans for recouping the cost of solar systems. Further, the solution to mitigating the regulatory burden associated with energy law compliance should not involve introducing classes of exemption specific to renewable energy projects. This is because the level of consumer protection could be compromised, which must be avoided in the context of embedded networks since past experience indicates that embedded network customers are at risk of abuse.

Of course, the above two issues are less pertinent if the OC confines the supply of solar energy to common property areas and the grid. But if residents are to access this electricity, two models are more preferable than the OC retrofitting the apartment with a solar system and an embedded network, and should be researched further. First, third-party solar PV providers like Allume mitigate most of the financial and associated governance issues discussed in Part IV(A). Further, the conditions imposed by the network service provider and selling exemption frameworks are less burdensome. However, the level of consumer protection available for residents purchasing electricity from third-party providers should be increased (at least to the extent necessary to ensure that it is commensurate with the nature of the particular supply arrangement). Secondly, these issues can also be mitigated if developers establish solar systems and embedded networks at the construction stage. However, the issue of third-line forcing remains a barrier to developers installing these systems. To help overcome this, the AEMC’s recommendations for promoting residents’ access to retail market competition in embedded networks should be adopted.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A Articles/Books/Reports

Altmann, Erika, Phillipa Watson and Michelle Gabriel, ‘Environmental Restriction in Multi-Owned Property’ in Erika Altmann and Michelle Gabriel (eds), Multi-Owned Property in the Asia-Pacific Region: Rights, Restrictions and Responsibilities (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2018) 119

Ashworth, Peta, Lygia M Romanach and Zaida Contreras-Castro, ‘Understanding Australian Householders’ Willingness to Participate in the Solar Distributed Energy Market’ (Paper presented at Energy Systems in Transition: Inter- and Trans-disciplinary Contributions, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany, 9-11 October 2013) <https://publications.csiro.au/rpr/download?pid=csiro:EP1310810&dsid=DS2>

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, ‘Restoring Electricity Affordability and Australia’s Competitive Advantage: Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry – Final Report’ (June 2018)

Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Economic Regulatory Framework Review: Promoting Efficient Investment in the Grid of the Future’ (Final Report, 26 July 2018) <https://www.aemc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-07/Final%20Report.pdf>

Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Final Report: 2018 Retail Energy Competition Review’ (15 June 2018)

Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Final: 2017 AEMC Retail Energy Competition Review’ (25 July 2017)

Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’ (Final Report, 28 November 2017)

Australian Energy Regulator, ‘Submission on Consumer Protections for Behind the Meter Electricity Supply – Consultation on Regulatory Implications’ (4 October 2016)

Australian National University, Energy Change Institute, ‘Submission to COAG Energy Council, Energy Market Transformation Team on Consumer Protections for Behind the Meter Electricity Supply: Consultation on Regulatory Implications’ (4 October 2016)

Benvenuti, Jo, ‘Consumer Access to External Dispute Resolution in a Changing Energy Market’ (Report to Energy and Water Ombudsman Victoria, Energy and Water Ombudsman NSW, and Energy and Water Ombudsman SA, 24 June 2016)

Consumer Action Law Centre and Consumer Utilities Advocacy Centre, ‘Consumer Protections for Behind the Meter Electricity Supply’ (4 October 2016)

Easthope, Hazel, Caitlin Buckle and Vandana Mann, ‘Australian National Strata Data 2018’ (City Futures Research Centre, Faculty of Built Environment, UNSW Australia)

Energy and Water Ombudsman NSW, ‘Consumer Protections for Behind the Meter Electricity Supply’ (4 October 2016)

Energy and Water Ombudsman Victoria, ‘Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Energy Council Consumer Protections for Behind the Meter Electricity Supply – Consultation on Regulatory Implications’ (5 October 2016)

Gabriel, Michelle and Philippa Watson, ‘Supporting Sustainable Home Improvement in the Private Rental Sector: The Views of Investors’ (2012) 30 Urban Policy and Research 309

Gabriel, Michelle et al, ‘The Environmental Sustainability of Australia’s Private Rental Housing Stock’ (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Final Paper No 159, December 2010)

Gabriel, Michelle et al, ‘The Environmental Sustainability of Australia’s Private Rental Housing Stock’ (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Positioning Paper No 125, January 2010)

Green, Jemma and Peter Newman, ‘Citizen Utilities: The Emerging Power Paradigm’ (2017) 105 Energy Policy 283

Green, Jemma and Peter Newman, ‘Planning and Governance for Decentralised Energy Assets in Medium-Density Housing: The WGV Gen Y Case Study’ (2018) 36 Urban Policy and Research 201

Green, Jemma, David Martin and Meagan Cojocar, ‘The Untouched Market: Distributed Renewable Energy in Multitenanted Buildings and Communities’ in Peter Droege (ed), Urban Energy Transition: Renewable Strategies for Cities and Regions (Elsevier, 2nd ed, 2018) 401

Hachem, Caroline, Andreas Athienitis and Paul Fazio, ‘Energy Performance Enhancement in Multistory Residential Buildings’ (2014) 116 Applied Energy 9

Hampel, Clare, Leigh Parker and Mark Baker, ‘Queensland Household Energy Survey 2017: Insights Report’ (Colmar Brunton, prepared for Energy Queensland, Powerlink) <https://www.powerlink.com.au/sites/default/files/2018-04/Queensland%20Household%20Energy%20Survey%20Report%202017_0.pdf>

Inglis, Kayla, Emily Mitchell and Robert Passey, ‘Recommendations for Implementing Virtual Net Metering into Community-Owned Renewable Energy Projects in Australia’ (Paper presented at Asia-Pacific Solar Research Conference, Brisbane Convention and Exhibition Centre, Queensland, Australia, 8-10 December 2015)

Lujanan, Martti, ‘Legal Challenges in Ensuring Regular Maintenance and Repairs of Owner-Occupied Apartment Blocks’ (2010) 2 International Journal of Law in the Built Environment 178

Mirvac, ‘“This Changes Everything” – Sustainability Report’ (2016)

Müller, Simon C and Isabell M Welpe, ‘Sharing Electricity Storage at the Community Level: An Empirical Analysis of Potential Business Models and Barriers’ (2018) 118 Energy Policy 492

Myors, Paul, Rachel O’Leary and Rob Helstroom, ‘Multi Unit Residential Buildings: Energy & Peak Demand Study’ (Energy Australia and NSW Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Natural Resources, October 2005)

Origin Energy, ‘Consumer Protections for Behind-the-Meter Energy Supply – Consultation Paper’ (4 October 2016)

Parliament of Victoria, Economic, Education, Jobs and Skills Committee, ‘Inquiry into Community Energy Projects’ (September 2017)

Public Interest Advocacy Centre, ‘Submission to the Draft Report AEMC Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’ (17 October 2017)

Roberts, Mike B et al, ‘Submission in Response to the AEMC’s Draft Report on the Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’ (Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets, UNSW Australia; Australian Photovoltaic Institute, 17 October 2017)

Roberts, Mike B et al, ‘Submission to the AEMC Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’ (Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets, UNSW Australia; School of Photovoltaic and Renewable Energy Engineering, UNSW Australia; Australian Photovoltaic Institute)

Roberts, Mike, Anna Bruce and Iain MacGill, ‘PV for Apartment Buildings: Which Side of the Meter?’ (Paper presented at Asia-Pacific Solar Research Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 5-7 December 2017)

Roberts, Mike, Anna Bruce and Iain MacGill, ‘PV in Australian Apartment Buildings – Opportunities and Barriers’ (Paper presented at Asia-Pacific Solar Research Conference, Brisbane Convention and Exhibition Centre, Queensland, Australia, 8-10 December 2015)

Schuster, Michael, ‘NABERS for Apartments: Review Report’ (Wattblock, prepared for NSW Department of Environment and Energy, 2017)

Sherry, Cathy, ‘Long-Term Management Contracts and Developer Abuse in New South Wales’ in Sarah Blandy, Ann Dupuis and Jennifer Dixon (eds), Multi-owned Housing: Law, Power and Practice (Routledge, 2010) 159

Sherry, Cathy, ‘The New South Wales Strata and Community Title Acts: A Case Study of Legislatively Created High Rise and Master Planned Communities’ (2009) 1 International Journal of Law in the Built Environment 130

Todoc, Jessie L, ‘Wiring the Southeast Asian City: Lessons from Urban Solar Applications in the Philippines’ in Peter Droege (ed), Urban Energy Transition: Renewable Strategies for Cities and Regions (Elsevier, 2nd ed, 2018) 335

UMR Research, ‘Usage of Solar Electricity in the National Energy Market: A Quantitative Study’ (Energy Consumers Australia, November 2016) <https://energyconsumersaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/UMR-Usage-of-solar-electricity-in-the-national-energy-market.pdf>

B Cases

Minister for Immigration & Citizenship v SZMDS (2010) 240 CLR 611

Plaintiff M70/2011 v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship; Plaintiff M106/2011 v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2011] HCA 32; (2011) 244 CLR 144

C Legislation

Australian Energy Market Commission, National Electricity Rules (at 5 October 2018)

Australian Energy Market Commission, National Energy Retail Rules (at 4 October 2018)

Body Corporate and Community Management Act 1997 (Qld)

Ley 49/60 de Propiedad Horizontal [Law 49/60 of Horizontal Property] (Spain)

Loi no 65-557 du 10 juillet 1965 [Law No 65-557 of 10 July 1965] (France) JO, 10 July 1965

National Electricity (South Australia) Act 1996 (SA)

National Energy Retail Law (South Australia) Act 2011 (SA)

Owners Corporation Act 2006 (Vic)

Strata Schemes Management Act 2015 (NSW)

Unit Title Schemes Act 2009 (NT)

Unit Titles (Management) Act 2011 (ACT)

D Other

Allume Energy, Building Owners <https://allumeenergy.com.au/portal>

Allume Energy, Technology <https://allumeenergy.com.au/technology>

Architecture and Design, Masterplanned Community in Sydney Goes Solar <https://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/news/masterplanned-community-by-sekisui-house-goes-sola>

Australian Broadcasting Corporation News, ‘Layout of Stucco as Solar Powered Embedded Network’ (21 June 2017) <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06-21/layout-of-stucco-as-solar-powered-emnedded-network/8639358>

Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘2016 Census QuickStats’ (2018) <http://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/036>

Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Apartment Living’ (Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia – Stories from the Census, 2016) <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Apartment%20Living~20>

Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Case Study – Slow Growth in Solar Power in Australian Homes’ (2015-16 Survey of Income and Housing, 2017)

Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Dwelling Structure by Dwelling Type (SA2+)’ (2016 Census of Population and Housing)

Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Table 20 – Number of Dwelling Units Approved in New Residential Buildings, Original-Australia’ (Building Approvals, Australia, Feb 2018) <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/8731.0Feb%202018?OpenDocument>

Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Distributed Energy Resources’ (2018) <https://www.aemc.gov.au/energy-system/electricity/electricity-system/distributed-energy-resources>

Australian Energy Market Commission, National Energy Customer Framework <https://www.aemc.gov.au/regulation/energy-rules/national-energy-retail-rules/national-energy-customer-framework>

Australian Energy Regulator, ‘AER (Retail) Exempt Selling Guideline’ (Version 5, March 2018)

Australian Energy Regulator, ‘Electricity Network Service Provider – Registration Exemption Guideline’ (Version 6, March 2018)

Australian Energy Regulator, Allume Energy Pty Ltd Retail Exemption, <https://www.aer.gov.au/retail-markets/retail-exemptions/public-register-of-retail-exemptions/55817-allume-energy-pty-ltd-retail-exemption>

ClearSky Solar Investments, How It Works <https://www.clearskysolar.com.au/howitworks.php>

Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, Australian Government, Environmental Upgrade Agreements NSW (24 September 2018) <https://www.business.gov.au/assistance/environmental-upgrade-agreements-nsw>

Department of the Environment and Energy, Australian Government, National Energy Customer Framework <https://www.energy.gov.au/government-priorities/energy-markets/national-energy-customer-framework>

Flow Systems, The Orchards <https://flowsystems.com.au/communities/orchards-energy/>

Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal New South Wales, ‘Solar Feed-in Tariffs 2018/19’ <https://www.ipart.nsw.gov.au/Home/Industries/Energy/Reviews/Electricity/Solar-feed-in-tariffs-201819>

Landcorp, Gen Y Demonstration Housing Project (17 June 2017) White Gum Valley <https://www.landcorp.com.au/innovation/wgv/Latest/Gen-Y-Demonstration-Housing-Project/>

Luke Wong, ‘Solar Power Switch Proves to be a Bright Idea for Students Who’ve Halved Their Electricity Bills’ (ABC News, 26 April 2018) <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-04-26/stucco-student-solar-power-energy-battery-cost-savings/9688892>

Mirvac Residential, ‘Solar Initiative’ (Ascot Green) <https://ascotgreen.mirvac.com/news-and-events/News/solar-initiative>

Parliament of Australia, ‘Feed-in Tariffs’ (2011) <https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Browse_by_Topic/ClimateChangeold/governance/domestic/national/feed>

Solar Choice, ‘Solar for Strata & Apartment Blocks: Everything You Need to Know (Almost)’ (10 July 2018) <https://www.solarchoice.net.au/blog/solar-for-strata-apartment-blocks/>

SolarCloud, Invest in Solar Power Without Touching Your Roof <https://www.solarcloud.com.au/>

Stucco, Solar <http://www.stucco.org.au/solar>

SunTenants, How It Works <https://www.suntenants.com/howitworks/>

Vorrath, Sophie, ‘Melbourne Apartment Complex Switches on Shared Solar System’ (One Step Off the Grid, 25 May 2018) <https://onestepoffthegrid.com.au/melbourne-apartment-complex-switches-shared-solar-system/>

Wattblock, Wattblock Case Studies <https://www.wattblock.com/>

Williams, Sue, ‘Sydney Apartment Block First to Retrospectively Instal Solar Panels, Now Has Half the Energy Bills’ (Domain, 27 April 2018) <https://www.domain.com.au/news/here-comes-the-sun-threestorey-apartment-block-installed-solar-panels-now-pays-half-the-energy-bills-20180427-h0z5iw/>

Williams, Sue, ‘Sydney Development The Orchards to Have One of World’s Biggest Rooftop Solar Panel Systems’ (Domain, 29 January 2018) <https://www.domain.com.au/news/sydney-development-the-orchards-to-have-one-of-worlds-biggest-rooftop-solar-panel-systems-20180129-h0pvct/>

[1] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Distributed Energy Resources’ (2018) <https://www.aemc.gov.au/energy-system/electricity/electricity-system/distributed-energy-resources>; Jemma Green, David Martin and Meagan Cojocar, ‘The Untouched Market: Distributed Renewable Energy in Multitenanted Buildings and Communities’ in Peter Droege (ed), Urban Energy Transition: Renewable Strategies for Cities and Regions (Elsevier, 2nd ed, 2018) 401, 401; Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Economic Regulatory Framework Review: Promoting Efficient Investment in the Grid of the Future’ (Final Report, 26 July 2018) <https://www.aemc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-07/Final%20Report.pdf> ii.

[2] Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, ‘Restoring Electricity Affordability and Australia’s Competitive Advantage: Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry – Final Report’ (June 2018) 5.

[3] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Final Report: 2018 Retail Energy Competition Review’ (15 June 2018) 137.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, above n 2.

[6] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Final Report: 2018 Retail Energy Competition Review’, above n 3, 136, citing International Energy Agency, ‘World Energy Outlook 2017: Executive Summary’ (OECD/IEA, 2017) 1.

[7] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Final Report: 2018 Retail Energy Competition Review’, above n 3, 139, citing International Energy Agency, ‘World Energy Outlook 2017: Executive Summary’ (OECD/IEA, 2017) 1.

[8] Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Case Study – Slow Growth in Solar Power in Australian Homes’ (2015-16 Survey of Income and Housing, 2017).

[9] Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘2016 Census QuickStats’ (2018) <http://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/036> Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Apartment Living’ (Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia – Stories from the Census, 2016) <http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Apartment%20Living~20> .

[10] The ratio of apartments to occupied houses grew from 1:7 to 1:5 between 1991 and 2016 respectively: Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Apartment Living’, above n 9, and 32 per cent of residential building approvals between January 2015 and July 2018 were for apartments: Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Table 20 – Number of Dwelling Units Approved in New Residential Buildings, Original-Australia’ (Building Approvals, Australia, Feb 2018) <http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/8731.0Feb%202018?OpenDocument> .

[11] Green, Martin and Cojocar, above n 1.

[12] Companies like ClearSky Solar Investments and SolarCloud allow people to invest in solar projects and receive payments or electricity bill credits corresponding to their investment: ClearSky Solar Investments, How It Works <https://www.clearskysolar.com.au/howitworks.php>; SolarCloud, Invest in Solar Power Without Touching Your Roof <https://www.solarcloud.com.au/>. There seems to be growing interest amongst apartment residents for these schemes, for eg, see: Clare Hampel, Leigh Parker and Mark Baker, ‘Queensland Household Energy Survey 2017: Insights Report’ (Colmar Brunton, prepared for Energy Queensland, Powerlink) 32 <https://www.powerlink.com.au/sites/default/files/2018-04/Queensland%20Household%20Energy%20Survey%20Report%202017_0.pdf>.

[13] Flow Systems, The Orchards <https://flowsystems.com.au/communities/orchards-energy/>.

[14] Sue Williams, ‘Sydney Development The Orchards to Have One of World’s Biggest Rooftop Solar Panel Systems’ (Domain, 29 January 2018) <https://www.domain.com.au/news/sydney-development-the-orchards-to-have-one-of-worlds-biggest-rooftop-solar-panel-systems-20180129-h0pvct/>.

[15] Caroline Hachem, Andreas Athienitis and Paul Fazio, ‘Energy Performance Enhancement in Multistory Residential Buildings’ (2014) 116 Applied Energy 9, 17-18.

[16] Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Dwelling Structure by Dwelling Type (SA2+)’ (2016 Census of Population and Housing).

[17] Stucco, Solar <http://www.stucco.org.au/solar> .

[18] Ibid.

[19] Sue Williams, ‘Sydney Apartment Block First to Retrospectively Install Solar Panels, Now Has Half the Energy Bills’ (Domain, 27 April 2018) <https://www.domain.com.au/news/here-comes-the-sun-threestorey-apartment-block-installed-solar-panels-now-pays-half-the-energy-bills-20180427-h0z5iw/>.

[20] Mike Roberts, Anna Bruce and Iain MacGill, ‘PV in Australian Apartment Buildings – Opportunities and Barriers’ (Paper presented at Asia-Pacific Solar Research Conference, Brisbane Convention and Exhibition Centre, Queensland, Australia, 8-10 December 2015) 3.

[21] Mirvac Residential, ‘Solar Initiative’ (Ascot Green) <https://ascotgreen.mirvac.com/news-and-events/News/solar-initiative>.

[22] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Final Report: 2018 Retail Energy Competition Review’, above n 3, 93.

[23] Peta Ashworth, Lygia M Romanach and Zaida Contreras-Castro, ‘Understanding Australian Householders’ Willingness to Participate in the Solar Distributed Energy Market’ (Paper presented at Energy Systems in Transition: Inter- and Trans-disciplinary Contributions, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany, 9-11 October 2013) <https://publications.csiro.au/rpr/download?pid=csiro:EP1310810&dsid=DS2> 13; Hampel, Parker and Baker, above n 12, 28 (for Queensland); UMR Research, ‘Usage of Solar Electricity in the National Energy Market: A Quantitative Study’ (Energy Consumers Australia, November 2016) 12 <https://energyconsumersaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/UMR-Usage-of-solar-electricity-in-the-national-energy-market.pdf>.

[24] Under the Strata Schemes Management Act 2015 (NSW); Owners Corporation Act 2006 (Vic); Unit Titles (Management) Act 2011 (ACT).

[25] Under the Strata Titles Act 1985 (WA); Body Corporate and Community Management Act 1997 (Qld); Unit Title Schemes Act 2009 (NT); Strata Titles Act 1988 (SA).

[26] Jessie L Todoc, ‘Wiring the Southeast Asian City: Lessons from Urban Solar Applications in the Philippines’ in Peter Droege (ed), Urban Energy Transition: Renewable Strategies for Cities and Regions (Elsevier, 2nd ed, 2018) 335, 346.

[27] Roberts, Bruce and MacGill, above n 20, 7.

[28] Cathy Sherry, ‘The New South Wales Strata and Community Title Acts: A Case Study of Legislatively Created High Rise and Master Planned Communities’ (2009) 1 International Journal of Law in the Built Environment 130, 133.

[29] Roberts, Bruce and MacGill, above n 20, 7.

[30] Ibid, citing Paul Myors, Rachel O’Leary and Rob Helstroom, ‘Multi Unit Residential Buildings: Energy & Peak Demand Study’ (Energy Australia and NSW Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Natural Resources, October 2005) 10.

[31] Wattblock, Wattblock Case Studies <https://www.wattblock.com/>.

[32] Roberts, Bruce and MacGill, above n 20, 7.

[33] Ibid, citing Myors, O’Leary and Helstroom, above n 30; Mike Roberts, Anna Bruce and Iain MacGill, ‘PV for Apartment Buildings: Which Side of the Meter?’ (Paper presented at Asia-Pacific Solar Research Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 5-7 December 2017) 4.

[34] Parliament of Australia, ‘Feed-in Tariffs’ (2011) <https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/Browse_by_Topic/ClimateChangeold/governance/domestic/national/feed>; Green, Martin and Cojocar, above n 1, 406; Kayla Inglis, Emily Mitchell and Robert Passey, ‘Recommendations for Implementing Virtual Net Metering into Community-Owned Renewable Energy Projects in Australia’ (Paper presented at Asia-Pacific Solar Research Conference, Brisbane Convention and Exhibition Centre, Queensland, Australia, 8-10 December 2015) 5.

[35] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Final Report: 2018 Retail Energy Competition Review’, above n 3, 136; Inglis, Mitchell and Passey, above n 34. For example, in NSW the benchmark range for solar feed-in tariffs in NSW for 2018-19 is 6.9-8.4 c/kWh, whilst between 2010 and 2011 they ranged between 20 and 60 c/kWh: Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal New South Wales, ‘Solar Feed-in Tariffs 2018/19’ <https://www.ipart.nsw.gov.au/Home/Industries/Energy/Reviews/Electricity/Solar-feed-in-tariffs-201819>; Parliament of Australia, above n 34.

[36] That is, individual lots would be in the position of the ‘standard customers’ as demonstrated in Diagram 1; Jemma Green and Peter Newman, ‘Planning and Governance for Decentralised Energy Assets in Medium-Density Housing: The WGV Gen Y Case Study’ (2018) 36 Urban Policy and Research 201, 208.

[37] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’ (Final Report, 28 November 2017) iii.

[38] Green and Newman, above n 36; Michael Schuster, ‘NABERS for Apartments: Review Report’ (Wattblock, prepared for NSW Department of Environment and Energy, 2017) 47; Green, Martin and Cojocar, above n 1, 414.

[39] Jemma Green and Peter Newman, ‘Citizen Utilities: The Emerging Power Paradigm’ (2017) 105 Energy Policy 283, 290; Simon C Müller and Isabell M Welpe, ‘Sharing Electricity Storage at the Community Level: An Empirical Analysis of Potential Business Models and Barriers’ (2018) 118 Energy Policy 492, 497; Green and Newman, above n 36, 207.

[40] See generally Green and Newman, above n 36.

[41] Landcorp, Gen Y Demonstration Housing Project (17 June 2017) White Gum Valley <https://www.landcorp.com.au/innovation/wgv/Latest/Gen-Y-Demonstration-Housing-Project/>; Green and Newman, above n 36, 207.

[42] Green and Newman, above n 36.

[43] Also referred to as ‘microgrids’. See, for eg, the Smart Community Speyer and Quartierspeicher Weinsberg projects in Germany: Müller and Welpe, above n 39, 497, 498.

[44] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 37, 12.

[45] Green, Martin and Cojocar, above n 1, 414; Todoc, above n 26; see also Green and Newman, above n 36, 211.

[46] Jo Benvenuti, ‘Consumer Access to External Dispute Resolution in a Changing Energy Market’ (Report to Energy and Water Ombudsman Victoria, Energy and Water Ombudsman NSW, and Energy and Water Ombudsman SA, 24 June 2016) 17.

[47] Roberts, Bruce and MacGill, above n 20, 8; Todo, above n 26, 347.

[48] Benvenuti, above n 46.

[49] Allume Energy, Building Owners <https://allumeenergy.com.au/portal>.

[50] Solar Choice, ‘Solar for Strata & Apartment Blocks: Everything You Need to Know (Almost)’ (10 July 2018) <https://www.solarchoice.net.au/blog/solar-for-strata-apartment-blocks/>; Sophie Vorrath, ‘Melbourne Apartment Complex Switches on Shared Solar System’ (One Step Off the Grid, 25 May 2018) <https://onestepoffthegrid.com.au/melbourne-apartment-complex-switches-shared-solar-system/>.

[51] Vorrath, above n 50.

[52] Allume Energy, Technology <https://allumeenergy.com.au/technology> (containing Diagram 2).

[54] Michelle Gabriel et al, ‘The Environmental Sustainability of Australia’s Private Rental Housing Stock’ (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Positioning Paper No 125, January 2010) 24, citing Tim Seelig, Terry Burke and Alan Morris, ‘Motivations of Investors in the Private Rental Market’ (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Positioning Paper No 87, May 2006) 21; Cathy Sherry, ‘Long-Term Management Contracts and Developer Abuse in New South Wales’ in Sarah Blandy, Ann Dupuis and Jennifer Dixon (eds), Multi-owned Housing: Law, Power and Practice (Routledge, 2010) 159, 160; Sherry, above n 28, 131.

[55] Sherry, above n 28, 131.

[56] Ibid 133, referring to the Strata Schemes Management Act 1996 (NSW) which was replaced by the Strata Schemes Management Act 2015 (NSW).

[57] See, for eg, Strata Schemes Management Act 2015 (NSW) s 108(1).

[58] See, for eg, ibid s 5(1).

[59] See, for eg, ibid s 108(1).

[60] Roberts, Bruce and MacGill, above n 20, 3.

[61] Ibid 6; Roberts, Bruce and MacGill, ‘PV for Apartment Buildings: Which Side of the Meter?’, above n 33, 7.

[62] Williams, ‘Sydney Apartment Block First to Retrospectively Install Solar Panels, Now Has Half the Energy Bills’ above n 19; Australian Broadcasting Corporation News, ‘Layout of Stucco as Solar Powered Embedded Network’ (21 June 2017) <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-06-21/layout-of-stucco-as-solar-powered-emnedded-network/8639358>; Luke Wong, ‘Solar Power Switch Proves to be a Bright Idea for Students Who’ve Halved Their Electricity Bills’ (ABC News, 26 April 2018) <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-04-26/stucco-student-solar-power-energy-battery-cost-savings/9688892>.

[63] Ibid.

[64] Gabriel et al, above n 54, 28; see also Michelle Gabriel et al, ‘The Environmental Sustainability of Australia’s Private Rental Housing Stock’ (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Final Report No 159, December 2010) 61-2; Green and Newman, above n 36, 204.

[65] Hazel Easthope, Caitlin Buckle and Vandana Mann, ‘Australian National Strata Data 2018’ (City Futures Research Centre, Faculty of Built Environment, UNSW Australia) 5, using the Australian Bureau of Statistics 2016 Census of Population and Housing; Gabriel et al, ‘The Environmental Sustainability of Australia’s Private Rental Housing Stock’, above n 54, 23.

[66] Judy Rex and Rebecca Leshinsky, ‘Sustainable Retrofits of Apartment Buildings: Developing a Process to Address the Barriers to Adoption’ in Colin Campbell and Junzhao Jonathan Ma (eds), Looking Forward, Looking Back: Drawing on the Past to Shape the Future of Marketing: Proceedings of the 2013 World Marketing Congress (Springer Cham, 2016) 284, 287. See also Gabriel et al, ‘The Environmental Sustainability of Australia’s Private Rental Housing Stock’, above n 54, 29.

[67] Erika Altmann, Phillipa Watson and Michelle Gabriel, ‘Environmental Restriction in Multi-Owned Property’ in Erika Altmann and Michelle Gabriel (eds), Multi-Owned Property in the Asia-Pacific Region: Rights, Restrictions and Responsibilities (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2018) 119, 127.

[68] Todoc, above n 26, 347.

[69] See, for eg, Strata Schemes Management Act 2015 (NSW) s 112(1).

[70] Roberts, Bruce and MacGill, above n 20, 8.

[71] Solar Choice, above n 50.

[72] Ibid.

[73] Vorrath, above n 50.

[74] According to Allume, at least six residents are required to opt in for installation to be viable: Parliament of Victoria, Economic, Education, Jobs and Skills Committee, ‘Inquiry into Community Energy Projects’ (September 2017) 102.

[75] Contained in a schedule to the National Electricity (South Australia) Act 1996 (SA), which has been adopted in Victoria, Queensland, NSW, and the ACT.

[76] Australian Energy Market Commission, National Electricity Rules (at 5 October 2018).

[77] Australian Energy Market Operator, ‘Fact Sheet: The National Electricity Market’ 2 <https://www.aemo.com.au/-/media/Files/Electricity/NEM/National-Electricity-Market-Fact-Sheet.pdf>.

[78] Contained in the National Energy Retail Law (South Australia) Act 2011 (SA), which has been adopted in Queensland, NSW and the ACT.

[79] NEL s 29(1)(a).

[80] Ibid s 15.

[81] Australian Energy Regulator, ‘Electricity Network Service Provider – Registration Exemption Guideline’ (Version 6, March 2018) 15.

[82] NEL s 11(1); NER cl 2.5.1(a), (d).

[83] Australian Energy Regulator, ‘Electricity Network Service Provider – Registration Exemption Guideline’, above n 81, 30.

[84] Ibid 32.

[85] Depending on whether the AER believes that a lower threshold should be used: ibid 76.

[86] Ibid.

[87] Ibid 36-8, 42-3.

[88] Ibid 32.

[89] NER cl 7.5A.2(a).

[90] Roberts, Bruce and MacGill, above n 20, 6.

[91] NERL s 88(1).

[92] Australian Energy Regulator, Allume Energy Pty Ltd Retail Exemption, <https://www.aer.gov.au/retail-markets/retail-exemptions/public-register-of-retail-exemptions/55817-allume-energy-pty-ltd-retail-exemption>.

[93] Australian Energy Regulator, ‘AER (Retail) Exempt Selling Guideline’ (Version 5, March 2018) 33.

[94] Ibid 31.

[95] Ibid 9.

[96] Ibid 10.

[97] Ibid 9.

[98] Image adapted from Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 37, 20.

[99] Mike B Roberts et al, ‘Submission in Response to the AEMC’s Draft Report on the Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’ (Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets, UNSW Australia; Australian Photovoltaic Institute, 17 October 2017) 4; Mike B Roberts et al, ‘Submission to the AEMC Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’ (Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets, UNSW Australia; School of Photovoltaic and Renewable Energy Engineering, UNSW Australia; Australian Photovoltaic Institute) 5; Interview with Sustainability Manager, Technical Services, Mirvac (Email, 19 October 2018).

[100] Roberts et al, ‘Submission to the AEMC Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 99, 4.

[101] Benvenuti, above n 46, 10.

[102] Martti Lujanan, ‘Legal Challenges in Ensuring Regular Maintenance and Repairs of Owner-Occupied Apartment Blocks’ (2010) 2 International Journal of Law in the Built Environment 178, 181, citing Loi no 65-557 du 10 juillet 1965 [Law No 65-557 of 10 July 1965] (France) JO, 10 July 1965 art 25.

[103] Lujanan, above n 101, citing Ley 49/60 de Propiedad Horizontal [Law 49/60 of Horizontal Property] (Spain) art 16 (which is now art 17(2)).

[104] Unit Titles (Management Act) 2011 (ACT) s 23(1); sch 3 cl 3.15. NB: ‘sustainability infrastructure’ includes related utility service connections and equipment (see Dictionary) so it would appear to include an embedded network that was to be used to distribute solar energy.

[105] Ibid ss 23(2)(d), (e).

[107] See, for eg, Plaintiff M70/2011 v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship; Plaintiff M106/2011 v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship [2011] HCA 32; (2011) 244 CLR 144; Minister for Immigration & Citizenship v SZMDS (2010) 240 CLR 611.

[108] See, for eg, Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, Australian Government, Environmental Upgrade Agreements NSW (24 September 2018) <https://www.business.gov.au/assistance/environmental-upgrade-agreements-nsw>.

[109] SunTenants, How It Works <https://www.suntenants.com/howitworks/>.

[110] Michelle Gabriel and Philippa Watson, ‘Supporting Sustainable Home Improvement in the Private Rental Sector: The Views of Investors’ (2012) 30 Urban Policy and Research 309, 317.

[111] Roberts et al, ‘Submission to the AEMC Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 99; Roberts et al, ‘Submission in Response to the AEMC’s Draft Report on the Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 99; Public Interest Advocacy Centre, ‘Submission to the Draft Report AEMC Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’ (17 October 2017) 7.

[112] Public Interest Advocacy Centre, above n 111, 8; Roberts et al, ‘Submission in Response to the AEMC’s Draft Report on the Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 99, 5-6.

[113] Contained in the NERL; Australian Energy Market Commission, National Energy Retail Rules (at 4 October 2018); National Energy Retail Regulations 2012 (SA), which has also been implemented in Queensland, NSW and the ACT: Australian Energy Market Commission, National Energy Customer Framework <https://www.aemc.gov.au/regulation/energy-rules/national-energy-retail-rules/national-energy-customer-framework>.

[114] Department of the Environment and Energy, Australian Government, National Energy Customer Framework <https://www.energy.gov.au/government-priorities/energy-markets/national-energy-customer-framework>; Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 37, 29.

[115] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 37, 29.

[116] Australian Energy Regulator, ‘Electricity Network Service Provider – Registration Exemption Guideline’, above n 81, 39, 43.

[117] Ibid 49.

[118] Australian Energy Regulator, ‘AER (Retail) Exempt Selling Guideline’, above n 93, 52.

[119] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Final Report: 2018 Retail Energy Competition Review’, above n 3, 38.

[120] Ibid 39, 46, 58.

[121] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 37, 41.

[122] Ibid 41.

[123] Ibid 106.

[124] Ibid.

[125] Ibid 107.

[126] Benvenuti, above n 46, 65.

[127] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 37, 101.

[128] For eg, see ibid 92, 117-18, 129.

[129] Australian Energy Regulator, ‘AER (Retail) Exempt Selling Guideline’, above n 93, 44.

[130] For eg: condition 3 (that, inter alia, exempt sellers include in their bill to customers the basis on which tariffs, fees and charges are calculated) (ibid 36); condition 7 (that, inter alia, exempt sellers must not charge customers tariffs higher than that which would be charged by a local retailer) (at 37); conditions 9 and 10 (prevent the exempt seller from swiftly disconnecting the customer) (at 38-40); condition 12 (providing flexible payment options to customers experiencing financial difficulty) (at 40).

[131] Ibid 42.

[132] Energy and Water Ombudsman Victoria, ‘Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Energy Council Consumer Protections for Behind the Meter Electricity Supply – Consultation on Regulatory Implications’ (5 October 2016) 2; Benvenuti, above n 46, 57. See further Consumer Action Law Centre and Consumer Utilities Advocacy Centre, ‘Consumer Protections for Behind the Meter Electricity Supply’ (4 October 2016) 11.

[133] Ibid.

[134] Ibid 54-5.

[135] Energy and Water Ombudsman NSW, ‘Consumer Protections for Behind the Meter Electricity Supply’ (4 October 2016) 5.

[136] Benvenuti, above n 46, 67; Australian National University, Energy Change Institute, ‘Submission to COAG Energy Council, Energy Market Transformation Team on Consumer Protections for Behind the Meter Electricity Supply: Consultation on Regulatory Implications’ (4 October 2016) 4.

[137] Energy and Water Ombudsman Victoria, above n 132, 3.

[138] Australian National University, Energy Change Institute, above n 136, 4-5.

[139] Australian Energy Regulator, ‘Submission on Consumer Protections for Behind the Meter Electricity Supply – Consultation on Regulatory Implications’ (4 October 2016) 6.

[140] Ibid; Energy and Water Ombudsman NSW, above n 135, 2.

[141] Energy and Water Ombudsman NSW, above n 135, 3.

[142] Origin Energy, ‘Consumer Protections for Behind-the-Meter Energy Supply – Consultation Paper’ (4 October 2016) 1.

[143] See Parts IV(A), IV(B), V(B).

[144] Green, Martin and Cojocar, above n 1, 414; Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 37, 42.

[145] Ibid.

[146] Green and Newman, above n 36, 211.

[147] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Final: 2017 AEMC Retail Energy Competition Review’ (25 July 2017) 150.

[148] Ibid 151.

[149] Ibid.

[150] Flow Systems, The Orchards, above n 13; Williams, ‘Sydney Development The Orchards to Have One of World’s Biggest Rooftop Solar Panel Systems’, above n 14; Architecture and Design, Masterplanned Community in Sydney Goes Solar <https://www.architectureanddesign.com.au/news/masterplanned-community-by-sekisui-house-goes-sola>.

[151] Mirvac, ‘“This Changes Everything” – Sustainability Report’ (2016) 35; Interview with Sustainability Manager, Technical Services, Mirvac (Email, 19 October 2018).

[152] Mirvac, above n 151, 35.

[153] Interview with Residential Sustainability Manager, Mirvac (Email, 9 October 2018).

[154] Australian Energy Market Commission, ‘Review of Regulatory Arrangements for Embedded Networks’, above n 37, 69-70, 73-4.

[155] See ibid vii for an overview.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJlStuS/2019/4.html