|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal Student Series |

A FUTURE FOR THE PAST – HERITAGE IN SINGAPORE

JENNY YEUNG *

Every society in search of identity and growth grapples with the need to reflect upon the past whilst looking forward into the future. This question is particularly acute for the land scarce (721.5km2) city-state of Singapore.[1] Since attaining independence in 1965, the ruling party’s ethos of pragmatism and political expedience – to ‘get things done to meet citizens’ development needs’ – has ‘tended to override... longer-term goals of protecting the environment for the benefit of future generations’.[2] The desire to avoid becoming a homogenised corporate urban landscape, however, has prompted a shift towards reclaiming Singapore’s tangible heritage. Since we all live in a built environment, heritage buildings provide a physical manifestation of sociocultural traditions that give a modern city its distinctiveness. Without these ‘visual landmarks, all other records of the past [like journals and photos] remain abstract... [and] difficult... to link to the present’.[3]

Despite the above, questions about who decides what deserves preservation are seldom contemplated. By highlighting the shifting economic and nation-building functions heritage plays, this paper investigates the processes and politics of conservation – of how an increasingly active citizenry is challenging a vision previously monopolistically defined by the Singapore state. Against this backdrop, it then turns to demonstrate how heritage laws in Singapore remain state-centric and rooted in an individualised conception of property. Noting this disjuncture, the paper argues that heritage laws need to adapt to the notion that heritage is increasingly understood and embraced as a democratic enterprise. Doing so enables people to appreciate that heritage is about contestation. Where the law provides a framework around which these contestations can occur inclusively and be resolved fairly, it has the power to transform urban heritage into a vehicle through which citizens learn to accommodate each other’s differences constructively. This in turn enables spatial intergenerational equity to be achieved in economically viable, socially vibrant and culturally rich ways.

I THE CONCEPT & FUNCTIONS OF HERITAGE

Decisions to conserve urban heritage are not neutral but rather subjective processes by which people choose some physical structures to safekeep whilst demolishing others for new developments. The web of interconnected subjective interests involved therefore means that heritage often serves different functions for different people. As such, the subsequent section examines the perspective of the state and that of citizens across three time periods. The first begins from 1965, a period marked by demolitions after Singapore gained independence from Britain and was expelled from the Malaysian Federation. The second is from the 1980s during which globalisation prompted the state to establish key conservation initiatives. Finally, the 2000s onwards marks a rise in civic participation in conservation debates as Singaporeans born with limited personal experiences of colonial deprivations become an increasingly large portion of the adult population. Putting aside these different viewpoints, heritage, at its heart, is unified by the notion of intergenerational equity. It views certain physical structures as bearers of economic, cultural, political and social value worth handing-down to future generations.[4] Heritage, therefore, can be conceptualised as a form of shared public inheritance.

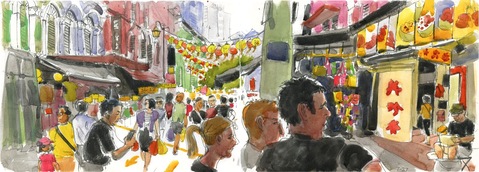

Shop-houses. [Conserved].[5]

A Heritage as Economic Commodity

If heritage buildings are valued purely as economic assets, they would be demolished when alternative uses produce greater financial returns. In other words, the ability of a site to generate profit in the short-term will play the most significant role in determining whether it is worth conserving. While conceiving of heritage in these financial terms is necessary as it helps allocate land, a finite resource, efficiently in a free market, it is important to only do so partially. This is not only because heritage is non-fungible, innately lacking in replacement value once destroyed, but also because monetary considerations need to be balanced against other things, such as a shared sense of place and history, which communities value.[6]

1 Heritage as Generator of Tourism Income

In the immediate post-independence period, the government’s focus on eradicating the colonial legacy of widespread economic deprivation saw it adopt an industrialisation strategy characterised by unconstrained demolition and rebuilding.[7] Arhictectural landmarks like shop-houses that were not bull-dozed also fell into disrepair as restrictive rent-control legislation aimed at ameliorating severe housing shortages disincentivised owners from restoring properties.[8]

In 1983 however, a sharp 3.5% fall in tourist arrivals spurred the government into realising that Singapore’s competitiveness depended on their ability to market its uniqueness.[9] In response, they deployed rhetoric that conjured up images of ‘oriental mystique’, blending exoticism with modernity.[10] The need to serve-up buildings that were authentic artefacts for outsiders’ global cultural consumption, and points around which to cultivate citizens’ sense of civic pride, drove conservation efforts.

After the state gazetted the Chinatown conservation area in 1986 for example, the owners of 1,200 buildings were given an opportunity to sell to the state, or to restore their properties at their own expense in accordance with stringent architectural guidelines.[11] These meticulous regulations preserving physical façades from the past were, contrastingly, accompanied by decisions to lift development and rent controls, [12] leaving trades to the vagaries of market competition. As rents tripled, elderly local residents and grocers serving them gave way to businesses with high-margin turnovers.[13] Supplementing these incentives which leveraged private financing into conservation, the state also invested S$97.5million into cooking and theatre venues along food street to give tourists a full sensory experience.[14]

Chinatown. [Conserved].[15]

While citizens earlier accepted the state’s policy of adaptive re-use without complaint, the 2000s brought more diverse, competing views. Some say that the eclectic mixing of shop-houses operating as gay clubs alongside international fashion labels and Samsui-women (immigrant labourer) themed boutique hotels are shining examples of how disparate factions can live in harmony.[16] For this group, such use of heritage is not only accepted as an inevitable part of progress, but embraced as a celebration of Singaporeans’ adaptable spirit and creative agency – a force responsible for growing tourism into a sector worth S$26.8billion annually.[17]

Nevertheless, others have criticised the top-down cultural re-engineering of Chinatown into a superficial ethnic theme park. Emotionally and historically significant, Cantonese, Hokkien and Teochiew migrants had set up hui-kuans (regional guildhalls) in Chinatown since the 1800s to welcome new arrivals.[18] The overemphasis on tourism however has drained away this indigenous clan-based urban culture, reducing the area into a mandarinised Chinese space in line with investor expectations. As local community groups like the Kreta-Ayer Citizen’s Consultative Committee are denied any decision-making powers and only entitled to information, they can do little except complain about the rise of standardised traditional herbalists or calligraphers who ‘freeze the place in a mood of perpetual festivity’.[19] The decision to preserve architectural structures and fragments of street life in ‘aesthetic...[though]...non-critical’ ways have sanitised history, [20] and fuelled the exclusion of low-income ‘residential communities once interwoven into the rhythm of [these spaces]’.[21] Socioeconomically non-inclusive heritage decision-making has hence flattened once culturally meaningful sites of history into mere sights of history for leisure consumption.

2 Heritage Sacrificed for Economy-boosting Infrastructure

Since 1965, the state has deployed rhetoric emphasising that Singapore’s survival depends on using scarce land efficiently in a competitive international marketplace.[22] Consequently, the idea that conservation is merely sentimental and cannot be afforded has become embedded in the national psyche. The emphasis on developing infrastructure to promote Singapore as a ‘world-class... city of opportunity’ demonstrates that this mentality persists today. [23] Nevertheless, citizens seeking to preserve their cultural connections have increasingly sought to ‘counter-script the [state’s] topographical aspirations’.[24]

In 2011 for example, the government revealed an amended Master Plan to build a highway across Bukit Brown cemetery to alleviate traffic congestion and free-up land for housing.[25] Since the announcement, heritage and nature civil society groups have launched a concerted campaign for Bukit Brown to be conserved as a public heritage park. Activists highlight that the development will irreversibly compromise the delicate ecological and heritage integrity of Bukit Brown – the largest Chinese cemetery outside China with over 200,000 graves.[26] Taking advantage of the greater connectivity and platforms for alternative expression outside state-controlled media, activists have used Facebook groups like ‘SOS Bukit Brown’ to organically share knowledge, mobilise fellow citizens to sign petitions and organise National Deceased Pioneers protests to lampoon the state’s National Day Parade.[27]

Bukit Brown Cemetery. [Gazetted for demolition].[28]

Characterising Bukit Brown as an authentic, transcendental space, activists highlight that gravestone epigraphs contain valuable historical information about prominent pioneers, and that Hungry Ghost rituals reveal age-old community cultural practices.[29] These artefacts, at a deeper level, reveal how Chinese dialect groups organised at the grassroots to resist colonial plans which sought to eliminate feng-shui customs for honouring the deceased in favour of rational city planning.[30] As such, Bukit Brown has become a meta-symbolic site for understanding Singaporean history in ways autonomous from the state-scripted narrative. Singapore’s semi-authoritarian government, one suspicious of those who challenge its authority, has historically subdued levels of social activism.[31] Bukit Brown however, in moving conservation activism from being a niche pastime for middle-class architects into the wider public consciousness, has become a test case. Rather than unquestioningly accepting the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s longstanding claim that ‘trade offs’ must be made to enable economic development,[32] 88% of Singaporeans surveyed complained that heritage decisions were too top-down.[33] In other words, it appears that citizens in this maturing society are seeking shared authorship to improve quality of life beyond economic prosperity.

B Heritage for Nation-Building

Place provides a concrete setting in which people are enmeshed in webs of activities and social relations of power. As globalisation becomes characterised by transient connections, anxiety about the frenetic pace of change and corruption by newfound materialism, heritage offers people a tangible sense of stability and cultural continuity.[34] Heritage and the nostalgia evoked is hence a constructive force. As Minister of State George Yeo put it, by ‘trac[ing] our ancestries... we form a clearer vision of our future... To be great, a nation must have a sense of its destiny’.[35] Echoing this view, 83% of citizens reported that a greater appreciation of history through heritage increased their sense of belonging to Singapore.[36]

The assumption that each hertiage landscape has a single unique identity however is inaccurate. Rather, heritage is a carefully curated enterprise. Historically, the state, as arbiter, has selectively given legal protection to particular sites whilst leaving others to face the possibility of being literally erased from the landscape and history.[37] When heritage is deployed as a rallying-point for nation-building, states often depict collective memories anchored to the materiality of a place as uncontested. Reminiscences inconsistent with the ideological agenda are cast as individual idiosyncrasies. The valorisation of selected sites to tell a linear narrative of state-driven progress is thus fraught with ‘selective remembering and institutional forgetfulness’.[38] Bearing these dynamics in mind, heritage landscapes are better conceived of as sites of contestation that are never fully defined as different sides lay claim to how they should be represented.

1 Heritage to Reinforce Narrative of Progress and Racial Harmony

Consonant with the narrative of economic survival, eradicaiton of basic problems like overcrowding in dilapidated shop-houses became the government’s priority upon attaining independence.[39] Doubling its rate of land acquisitions,[40] the state knocked-down heritage buildings and built new Housing Development Board units with improved sanitation and privacy.[41] Citizens lifted out of economic deprivation in turn developed a tacit obedience and unquestioning loyalty to the state.

In the 1980s however, falling tourism revenues and the sense of displacement engendered by globalisation prompted the government to release its first Conservation Master Plan (1986). Rather than grappling with the open-textured mutations and permutations of colonialism, nationalism and capitalism,[42] the Plan oriented conservation towards projecting a unidirectional march of progress.[43] To resist being assimilated into the West, it encouraged Singaporeans to ‘draw inspiration’ from the nation’s ‘Asian roots’.[44]

A core area the first Master Plan gazetted was the civic district with colonial buildings including City Hall, Victoria Theatre and Boat, Clarke and Robertson Quay. Through adaptive reuse, the area has since been turned from a working river into a world-class dining and entertainment district hosting iconic public events including the Lunar New Year River Hong-bao.[45] The preserved colonial buildings serve as a foil against which the state tells its narrative of Singapore's transformation into a proud independent nation.[46] Intended to epitomise Asian dynamism and provide a new basis for collective memory, the area blends culture and economy, refashioning tradition in modernised and sophisticated ways.

Civic District – Singapore River with the Empress Place Building, Victoria Theatre and the Old Supreme Court. [Conserved].[47]

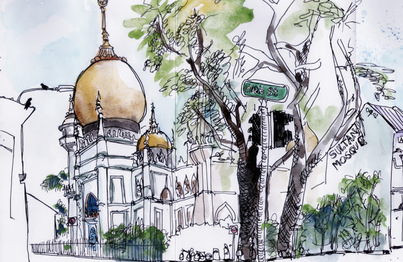

The first Master Plan also gazetted Singapore’s three ethnic enclaves – Chinatown, Little India, and Kampong Glam. In listing these sites, the government sought to replace the colonial legacy of racial segregation with multiculturalism and egalitarianism as the new foundational ideologies behind being Singaporean.[48] Heritage areas became physical manifestations of the state’s CMIO (Chinese, Malay, India and Other) multi-racial policy, demonstrating that separate but equal races could form a nation of one people living in harmony. Kampong Glam, for example, is said to be the heartland for Malay-Muslims – a group comprising 15% of the population. With the sultan mosque at its heart, buildings with mosaic tile designs have been conserved to evoke an ambiance that celebrates maritime traders’ contributions to Singapore’s cosmopolitism.[49]

Sultan Mosque in Kampong Glam. [Conserved].[50]

Since the 2000s however, Singaporeans have become increasingly conscious that the state was selectively emphasising aspects of heritage that highlighted its pivotal role in founding the now successful nation. Citizens have since voiced a desire to turn such ‘spaces of representation’ – spaces politicians used instrumentally to enact policy and shore-up political support, into ‘representational spaces’ – spaces that meaningfully capture the biographies of their everyday lives.[51]

In this light, many Singaporeans have expressed that the Civic District reproduces a version of trading history steeped in excessive consumerism at the expense of utilitarian geographies like second-hand markets that were historically significant to itinerant workers.[52] Further, with 83% preferring to prioritise historical accuracy over strictly formal equal representation of Singapore’s four racial groups,[53] it is unsurprising that some citizens are concerned about the state’s orientalisation of Malay-Muslims as Arab traders in Kampong Glam. This attempt to fold a narrow version of Malay-ness into the national imagination of multiculturalism suppresses the area’s rich subversive history of race riots and communal activism.[54] Since its formal heritage revitalisation, the community once built around the traditional Malay practice of allowing goods to spill-over from private shops onto shared five-foot ways has since disappeared from Kampong Glam.[55] While many have highlighted that the loss of heritage can result in feelings of dislocation,[56] non-inclusive conservation efforts appear to cause similarly negative outcomes.

Responding to shifts in community sentiment, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) launched extensive public consultations in 2001. Through holding exhibitions, receiving letters and convening subject groups comprising of businesses, non-government organisations and local residents, the URA sought to align their city-enhancement plans with ‘places [people] already held close to their hearts’.[57] This culminated in the 2003 Master Plan which extended conservation to preserving the old world charm of local neighbourhoods. The failure to heritage-list once familiar mosaic playgrounds in public housing estates many have lauded for organically growing communities ties,[58] however, suggests that only public views endorsing planners’ proposals were ultimately accepted.

Mosaic playground in Dakota – one of Singapore’s ‘heartlands’ (local neighbourhoods). [At risk of demolition].[59]

The latest development along this line is the government’s S$66million Heritage Plan. Launched in 2017, it aims to ‘create a cohesive society’ and celebrate the ‘multicultural heritage [which] anchors Singapore’s identity’ by showcasing heritage trails in local estates, enlivening historic precincts with programs, and ‘supporting ground-up initiatives that facilitate inter-community understanding’.[60] Despite its emphasis on community, whether this new plan will lead the government to embrace more diverse and dissenting voices is yet to be seen.

II HERITAGE IN THE LAW

From the above, it is evident that while the Singaporean state initiated heritage conservation for economic and nation-building purposes in the 1980s, citizens have since sought to participate to make this enterprise more inclusive and democratic. This section turns to examine whether the legal framework governing conservation has kept pace with this trend. Before addressing such a question, the paper first introduces the agencies administering Singapore’s heritage legislation.

A Legal Framework and Agencies

The National Heritage Board (NHB) established under the National Heritage Board Act (‘NHB Act’) is a statutory board under the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth comprising of members appointed by the Minister,[61] and staff appointed in accordance with the Public Sector (Governance) Act.[62] As Singapore’s leading agency on conservation, it is responsible for managing museums, raising public awareness about nationally significant sites, and advising the government on conservation-related policy and regulatory matters.[63] In 2009, the NHB took over the mandate formerly assigned to the Preservations of Monument Board by the Preservations of Monument Act (‘PM Act’) to develop a more integrated heritage ecosystem.[64] In this role, the NHB is empowered ‘to identify monuments... of historic, cultural, traditional, archaeological, architectural, artistic or symbolic significance and national importance’ and ‘make recommendations to the Minister for...[their]...preservation.[65] Once heritage-listed, the NHB has authority to make binding decisions for the maintenance of these monuments[66] subject to the Minister’s decision if its enforcement notices are appealed.[67]

The second agency that factors heritage into land-use planning is the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), a statutory board under the Ministry of National Development with appointment processes akin to the NHB.[68] As the national planning agency, the URA exercises extensive powers under the Planning Act, and when given written approval, exercises further powers the Minister delegates directly to it.[69] At its core, the URA translates the strategic direction it develops in Concept Plans into detailed 15-year Master Plans outlining zoning and density control measures with the aim of maximising the commercial and residential potential of land in Singapore.[70] Closely related, it also bears the responsibility of granting planning permission for all development applications.[71] From 1988, the URA’s role further expanded to advising the Minister to designate a single or a group of buildings with ‘special architectural, historic, traditional or aesthetic interest’ a conservation area.[72] It also began to issue binding guidelines on model conservation practices, including the range of permissible physical alterations and uses of conserved buildings.[73]

B Legal Critique

When viewed in an integrated way, two legal critiques can be levelled at the three main pieces of legislation governing heritage in Singapore.

1 NHB Lacks Legal Force vis-à-vis the URA

Though the NHB Act may have vested in the NHB the broadest, most inclusive mandate to safeguard Singapore’s heritage, the NHB’s power to effectively carry out this mandate is practically constrained by the URA. This is most evident when one notes that the NHB governs the ‘preservation of monuments’ under the PM Act completely separately from the URA which governs ‘conservation areas’ under the Planning Act.[74] Though listed monuments preserved under the PM Act receive greater legal protection from interference than whole areas gazetted under the Planning Act, the latter enables the making of more holistic, less building-centric decisions about heritage. The lack of linkage between these two legal regimes is particularly problematic as the URA wields full authority to make these broad decisions without having to consult the NHB – the agency possessing greater dedicated specialist expertise.[75]

This legal disjuncture practically curtails the ability of the NHB, the peak heritage body, from amplifying citizens’ desire for more inclusive preservation of cherished local scenes.[76] Framed another way, the current legal regime indirectly confines the NHB to proposing monument listings that isolate grand individual buildings suited to conveying state-centric narratives rather than capturing people’s dynamic interactions with the built environment in ways meaningful and socially significant to them.[77] This exacerbates the likelihood that less powerful communities will continue to be ideologically and factually excluded from conservation.

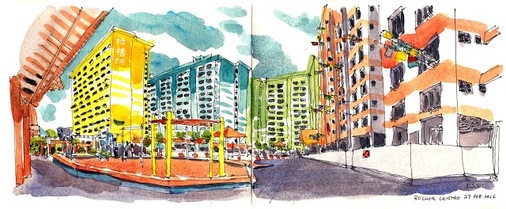

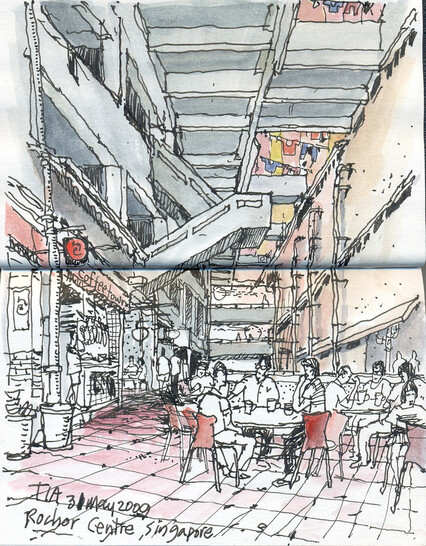

Rochor Centre – iconic HDB (public housing) flats. [Demolished in 2018 to make way for North-South Corridor expressway].[78]

Along a similar line, even where the NHB is concerned that a land development the URA approves under the Planning Act may be detrimental to the heritage value of a site, no legislation expressly confers power on the NHB to inquire into, let alone intervene, in the URA’s development approval process. As a corollary, neither the URA itself nor those applying for development permission under the Planning Act are legally required to consult the NHB about the potential heritage impact of their proposals.[79]

Together, the above examples illustrate a mismatch between the NHB’s broad mandate to serve as the guardian of heritage for all Singaporeans and its lack of legal power to influence the very land-use decisions affecting these heritage spaces. By giving the URA power to act at the exclusion of the NHB, the current regime minimises delay and costs to development that may otherwise arise if heritage considerations are actively taken into account. It thus appears that the existing legislation exhibits a bias towards favouring efficient land-use that maximises immediate wealth and utility even though doing so may be inconsistent with the sustainability objectives that lie at the heart of heritage conservation.[80]

Traditional void deck in Rochor Centre. [Demolished in 2018 resulting in loss of community].[81]

2 Limited Scope for Objections to Conservation Decisions

Furthermore, the narrowness of the class of persons able to make objections to decisions under the Planning Act and PM Act demonstrates that heritage, to an extent, continues to be conceived of like any ordinary form of private property. Exercising its powers under the Planning Act, the URA can grant an applicant permission to carry out building works within a conservation area.[82] While these works, such as a material change to the use of a building, could significantly impact the heritage integrity of the surrounding area, the Planning Act is silent on whether neighbouring owners or occupiers can object to permission being granted. When it comes to gazetting a monument, the PM Act suffers a similar shortcoming, albeit offering slightly broader grounds for complaint. Under the Act, the ‘owner and occupier of the monument and any land adjacent thereto which will be affected by the making, amendment or revocation of the preservation order’ are notified and given an opportunity to voice their concerns.[83]

Considering that heritage sites are a national inheritance all citizens share and changes to them leave indelible marks on Singapore’s physical and cultural landscape, it is problematic that both above pieces of legislation currently leave little room for interested third-parties to express their objections. This absence of a statutory right to voice concerns leave aggrieved third-parties the possibility of resorting to judicial review to challenge a decision.[84] Pursing this legal option however entails prohibitive costs. It also requires a complainant to overcome difficulties such as proving they have sufficient standing, and that the URA or NHB had breached an established ground of review in administrative law. These factors considered, it is unsurprising that despite vocal public protests over certain sites like Bukit Brown, no attempt to seek judicial review has been made to date.

Sungei Road Thief Market in operation since 1930 near Rochor. [Demolished in 2017 for a new train station. Application to government for relocation denied].[85]

While the above two critiques are illustrative rather than comprehensive, they demonstrate that the body of heritage law in Singapore, does not promote, as its normative ends, intergenerational equity. Rather, the fact that current laws constrain the NHB’s legal power and limit classes of persons able to challenge decisions, suggests that heritage continues to be predominantly conceived of as a form of private property. Consequently, existing legal discourse appears primarily concerned with making property transactions and developments economically efficient. It maximises peoples’ freedom to do what they want with a site subject only to minimal levels of interference by immediate neighbours and government agencies. This individualistic approach is aligned with the traditional conception of property as a bundle of rights over a scarce resource. These rights are devised to enable individuals to exercise dominion over land and then extract wealth to the exclusion of everyone else.[86] Situating heritage within this utilitarian and acquisitive legal framework necessarily inhibits the values of long-term democratic stewardship from taking hold.[87]

C Recommendations for Reform

The above critiques uncover the competing ideologies underlying the law. They reveal that because existing legal instruments continue to conceptualise heritage as an individualised form of property, laws have failed to account for people’s changing view of heritage. As evidenced by the rise of dissenting voices challenging approaches to conservation in Chinatown, Bukit Brown, the Civic District and Kampong Glam since the 2000s, it is clear that heritage sites are increasingly understood as cherished sites of ongoing contestation. This paper therefore proposes that heritage laws should be amended to reflect these changes. Doing so better enables heritage to deliver on its promise of securing a society’s shared public inheritance equitably across generations.

Having earlier canvassed the changing understanding of heritage from the perspective of different actors across time, it is evident that conflicting views are sometimes too different to be reconciled or accommodated. At other times though, compromises can be reached, conserved buildings can compatibly serve multiple divergent functions and heritage can recognise the multiplicity of dimensions on an urban scene.[88] As there will always be competing demands on whether property on scarce land should be preserved or demolished to meet housing or commercial needs, law and policy, however well crafted, cannot deliver outcomes that please all parties every time.

As Fincham notes, ‘any set of laws... governing objects of culture must account for the vibrancy of culture... Property, [as understood in law,] is fixed, possessed, controlled by its owner and alienable. Culture is none of these things... Cultural property claims tend to fix culture, which if anything is unfixed... and unstable’.[89] To remain sensitive to this dynamic concept of culture, the following recommendations are oriented to creating a non-prescriptive and flexible legal framework in which decision-making about heritage is equitable and inclusive. It aims to give different groups, including the marginalised, a fair opportunity to express and have their views properly considered. The law, in other words, seeks to bring diverse voices across the community into the fold of an ongoing, ever-changing conversation about their shared physical landscape. Doing so leaves the final task of assessing the substantive merits behind heritage-related decisions to policymakers.

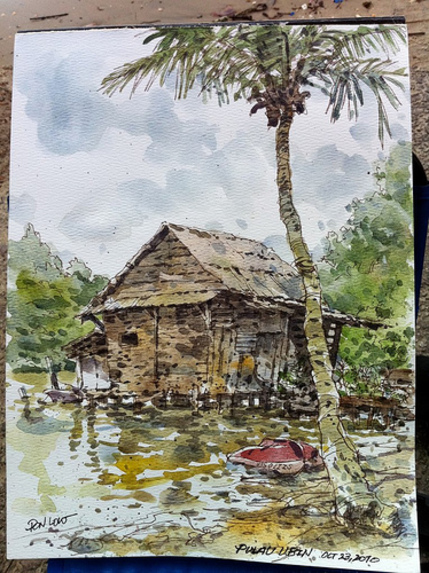

Pulau Ubin – Singapore’s last traditional ‘kampong’ (village). [Conserved with extensive civil society support for local communities].[90]

1 Empowering the NHB

In response to the above shortcomings, the law should be amended to mandate the URA to consult the NHB in any decision to gazette a conservation area. Similarly, URA planners and those submitting development applications should be required to cross-check their proposal against the tangible heritage registry the NHB is creating from its two-year nationwide survey.[91] Where the proposed development is occurring on sites where heritage value has been identified, the developer will be required to conduct a more extensive heritage impact assessment which they then submit to the NHB for review. These assessments enable the effect a development has on the structural integrity and cultural life associated with built heritage to be holistically understood. As such, they offer a sound basis for making decisions about heritage integration, mitigating adverse impacts or, at the very least, documenting and preserving records before demolition.[92] While an in-depth discussion of how heritage impact assessments should be implemented in Singapore lies beyond the scope of this paper, guidance is available from comparable jurisdictions like Hong Kong.[93]

While the URA should, as the agency responsible for balancing land-use considerations, retain the ultimate authority to make decisions about conservation areas and development approvals, expanding the legal power of the NHB gives it the ability to go beyond tokenism to influence these decisions. By nature of its more focused mandate, the NHB, through its everyday work of raising awareness and endearing Singaporeans to their heritage, has become a focal point for consolidating the many views it gathers from the public, stakeholders and experts.[94] Legally requiring the URA to consult the NHB hence gives these views an outlet into the planning process, concretely fulfilling the Singaporean government’s Heritage Plan goal of ‘incorporating heritage considerations into planning’.[95] The proposed step-wise escalation to mandate heritage impact assessments likewise strikes an appropriate balance that accounts for issues of intergenerational equity without unduly increasing the cost and time of development.

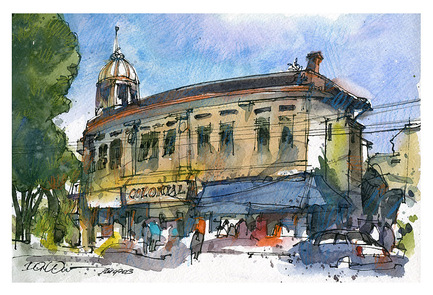

Ellison Building. [Partially conserved after concerted lobbying by heritage activists led to alteration of planned highway development].[96]

2 Institutionalising Substantive Public Participation at the Micro Level

To supplement the URA’s efforts to solicit public input at the macro policy level when developing its Master Plans,[97] the wider community should also be given a legal avenue to voice heritage-related concerns at a micro level. Specifically, decisions to carry out works on buildings in conservation areas (under the Planning Act) or to gazetted national monuments (under the PM Act) should be recorded on a register the public can inspect.[98] Further, interested parties should be able to make representations for or against these plans to the Minister – the ultimate decision-maker. The above recommendations bring the process for altering the status or use of a heritage site in line with existing procedures for amending Master Plans.[99]

The proposed amendment is intentionally non-prescriptive. Rather than setting a legislative threshold for halting development, it seeks only to give those concerned a voice, leaving the Minister full discretion to respond to submissions as a matter of policy. The Minister, serving as mediator between bureaucrats, developers and the community hence has the duty of giving proper consideration to views expressed by all sides. When done well, compromises will likely be brokered, and different parties, feeling they have been heard, are less likely to resent the final outcome even if it does not accord with their preferred views. While this proposal to increase transparency and opportunities for public participation may lengthen the time taken for approval processes, it is an appropriate trade off considering the potentially irreversible changes to the country’s shared inheritance.

Queenstown wet market – part of Singapore’s first satellite city. [Conserved after local residents published a book on the community’s heritage].[100]

Together, the proposed reforms shift the legal conception of heritage away from individual, utilitarian values underpinning conventional property doctrines. In its place, they provide a more principled basis for preserving tangible structures that are non-fungible and cherished by the collective as having intrinsic value over time.[101] In legally carving out space for citizens to have a voice – whether through the NHB or making specific claims, the law in effect acknowledges that the goal of heritage preservation is not to reproduce national subjects compliant with the state’s philosophy. As Lim put it, ‘contestations [over] public spaces should not be viewed as antagonistic anti-establishment actions but opportunities for ordinary citizens to present alternatives as stakeholders’,[102] and learn to embrace pluralism.

Notwithstanding the fact that the meanings attached to spaces differ between groups and across time, and that decisions often may only please some whilst disappointing others, laws that democratise heritage benefit a city and its people. In creating a framework around which respectful contestation is encouraged and all views are given due consideration in decision-making, the law transforms heritage into a vehicle through which people gain an appreciation of what it means to be active citizens shaping the built environment they share. The process of collectively deciding what to include and exclude from conservation contributes to the mutual education of people as they are led to see from another’s perspective of what beauty and value can look like in terms of architecture, history or social interaction.

Conservation is therefore most effective when it is genuinely an inclusive, collaborative partnership that reflects the coming together of people from diverse backgrounds.[103] In actively involving the community in heritage decision-making, they are given an ‘unparalleled opportunity to [regain a sense of identity stemming from a common past] and correct some of their sense of alienation... so characteristic of modem society’.[104] As such, it is unsurprising that even international law on heritage including the Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas emphasises the importance of public participation to successful conservation.[105]

III CONCLUSION

The way urban heritage has been conceived in Singapore has changed markedly over time. These spaces are constantly being adapted, constructed and interpreted by individuals, interest groups and state actors seeking to shape the nation’s collective memory. Against a backdrop in which the government used heritage to legitimate its role in transcending the colonial legacy of economic deprivation and racial segregation, citizens who view heritage as their common inheritance have expressed discontent. Increasingly, they have voiced concerns about the commodification of Chinatown and the Civic District, and the silencing of dissident narratives in Bukit Brown and Kampong Glam.

Heritage laws in Singapore, however, have not evolved to accommodate the fact that citizens want decisions pertaining to these sites to be made more inclusively and democratically. Instead, existing laws give the URA significantly broader powers than the NHB and set narrow limits on who can challenge heritage-related development decisions. Doing so embeds heritage within an individualised conception of property. Such framing, in turn, has favoured utilitarian extraction at the expense of carefully considering issues of intergenerational equity.

To minimise the irreversible heritage losses caused by the exclusion of local communities from decision-making under the current legal framework, this paper argues that the law should be amended to establish a structure that enables greater public participation in conservation. Specifically, it proposes expanding the NHB’s power in line with its mandate and giving interested third-parties an opportunity to voice objections to individual development decision relating to heritage. By bringing the law in line with empirical shifts in how heritage is conceptualised, the connection between a heritage site and the community that gives the site its meaning will more likely be sustained.

Though conflicting interests cannot always be reconciled, an opportunity for open, inclusive contestation is conducive to producing heritage spaces in which national cohesion and identity are borne from a respect for diversity. ‘In a microcosmic way, negotiations and decision-making in the world of urban heritage conservation reflect a larger social compact evolving, with multiple voices, sometimes testing the limits... but often focused on what is best for Singapore’.[106] When heritage is treated as an intergenerational public good that all citizens have an opportunity to shape, its potential to make an economic, social, political and cultural contribution to a nation are greatly enhanced.

* BSRAP/LLB, University of New South Wales. I thank Associate Professor Cathy Sherry for her guidance and encouragement in developing this paper. Sincere thanks also to Urban Sketchers for their permission to use their membersR[1] artworks in this publication.

1 Data.gov.sg, Total Land Area of Singapore (31 October 2018) Government of Singapore <https://data.gov.sg/dataset/total-land-area-of-singapore>.

[2] Jack Tsen-Ta Lee, ‘A Presence of the Past: The Legal Protection of Singapore's Archaeological Heritage’ (2013) 20 International Journal of Cultural Property 257, 271.

[3] Brenda Yeoh and Shirlena Huang, ‘Strengthening the Nation’s Roots? Heritage Policies in Singapore’ in Lian Kwen Fee & Tong Chee Kiong (eds), Social Policy in Post-Industrial Singapore (Brill, 2008) 201, 206.

[4] Angela Dimery, ‘Heritage Regulation and Property Rights’ (2013) 17 New Zealand Journal of Environmental Law 195, 209; Derek Fincham, ‘The Distinctiveness of Property and Heritage’ (2011) 115 Penn State Law Review 641, 668; Miroslaw Michal Sadowski, ‘Cultural Heritage and the City: Law, Sustainable Development, Urban Heritage and the Cases of Hong Kong and Macau’ (2017) 8 Romanian Journal of Comparative Law 208, 220.

[5] Sanjukta Sen, Rediscovering Singapore through Urban Sketching (14 January 2016) Urban Sketchers <http://www.urbansketchers.org/2016/01/rediscovering-singapore-through-urban.html> .

[6] Dimery, above n 4, 228.

[7] Yunci Cai, ‘Law and its Impact on Singapore’s Built Heritage’ in Kevin Y.L. Tan & Michael Hor (eds), Encounters with Singapore Legal History: Essays in Memory of Geoffrey Wilson Bartholomew (Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, 2009) 86, 103-4; Shirlena Huang and Brenda Yeoh, ‘The Conservation-Redevelopment Dilemma in Singapore: The Case of the Kampong Glam Historic District’ (1996) 13 Cities 411, 411.

[8] Lily Kong, ‘Conserving Urban Heritage: Remembering the Past in a Developmental City State’ in Heng Chye Kiang (ed), 50 Years of Urban Planning in Singapore (World Scientific Publishing, 2016) 237, 240; Jieming Zhu, Loo-See Sim and Xuan Liu, ‘Place Remaking under Property Rights Regimes: A Case Study of Niucheshui, Singapore’ (2007) 39 Environment and Planning 2346, 2356.

[9] T.C. Chang, ‘From ‘Instant Asia’ to ‘Multifaceted Jewel’: Urban Imaging Strategies and Tourism Development in Singapore’ (1997) 18 Urban Geography 542, 544; Yeoh and Huang, above n 3, 204.

[10] Chang, above n 9, 553-5; Andrea Ong, ‘Building on Shifting Sand: The Contested Terrain of Urban Heritage Legislation in India, Hong Kong and Singapore’ (2016) 34 Singapore Law Review 219, 244; Brenda Yeoh, ‘From Colonial Neglect to Post-Independence Heritage: The Housing Landscape in the Central Area of Singapore’ (2000) 12 City & Society 103, 118; Yeoh and Huang, above n 3, 205.

[11] Loo Lee Sim, ‘Urban Conservation Policy and the Preservation of Historical and Cultural Heritage: The Case of Singapore’ (1996) 13 Cities 399, 401-2; Belinda Yuen, ‘Searching for Place Identity in Singapore’ (2005) 29 Habitat International 197, 201; Zhu et al, above n 8, 2355-6.

[12] Cai, above n 7, 112; Kong, above n 8, 240.

[13] Sim, above n 11, 402; Yeoh, above n 10, 116; Brenda Yeoh and Lily Kong, ‘Singapore’s Chinatown: Nation Building and Heritage Tourism in a Multiracial City’ (2012) 2 Localities 117, 141-2.

[14] Yeoh and Huang, above n 3, 208.

Similar criticisms apply to Little India. For more, see: T.C. Chang, ‘Singapore's Little India: A Tourist Attraction as a Contested Landscape’ (2000) 37 Urban Studies 343; Joan Henderson, ‘Managing Urban Ethnic Heritage: Little India in Singapore’ (2008) 14 International Journal of Heritage Studies 332.

[15] Virginia Hein, Singapore (18 August 2015) Urban Sketchers <http://www.urbansketchers.org/2015/08/singapore.html> .

[16] Joan Henderson, ‘Understanding and Using Built Heritage: Singapore’s National Monuments and Conservation Areas’ (2011) 17 International Journal of Heritage Studies 46, 56; Peggy Teo and T.C. Chang, ‘The Shophouse Hotel: Vernacular Heritage in a Creative City’ (2009) 46 Urban Studies 341, 351-2; Yeoh and Kong, above n 13, 143.

[17] Singapore Tourism Board, Singapore Tourism Sector Performance Breaks Record for the Second Year Running in 2017 (12 February 2018) Singapore Tourism Board <https://www.stb.gov.sg/news-and-publications/lists/newsroom/dispform.aspx?ID=744>.

[18] Cai, above n 7, 116-8; Yeoh and Kong, above n 13, 121-2.

[19] Joan Henderson, ‘Conserving Heritage in South East Asia: Cases from Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines’ (2012) 37 Tourism Recreation Research 47, 52; Kong, above n 8, 252; Yuen, above n 11, 208; Zhu et al, above n 8, 2358-9.

[20] Teo and Chang, above n 16, 355.

[21] Yeoh, above n 10, 120.

[22] Joan Henderson, ‘Conserving Hong Kong’s Heritage: The Case of Queen’s Pier’ (2008) 14 International Journal of Heritage Studies 540, 550.

[23] Committee on the Future Economy, Report of the Committee on the Future Economy: Pioneers of the Next Generation (February 2017) Government of Singapore <https://www.gov.sg/~/media/cfe/downloads/cfe%20report.pdf?la=en>, 41.

[24] Khiun Liew Kai and Natalie Pang, ‘Neoliberal Visions, Post-Capitalist Memories: Heritage Politics and the Counter-Mapping of Singapore’s Cityscape’ (2015) 16 Ethnogeography 331, 333.

[25] Land Transport Authority, Construction of New Dual Four-Lane Road to Relieve Congestion along Pie & Lornie Road and Serve Future Developments (12 September 2011) Land Transport Authority <https://www.lta.gov.sg/apps/news/page.aspx?c=2&id=rj2i4o1u3d7018466v86y82epxjj32mwbvnhu6rpwt8lplkgo6>.

[26] William S.W. Lim, ‘Spatial Justice – A Singapore Case Study’ in William Siew Wai Lim (ed), Public Space in Urban Asia (World Scientific, 2014) 235, 241-2; Singapore Heritage Society, Position Paper on Bukit Brown (January 2012) Singapore Heritage Society <http://www.singaporeheritage.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/SHS_BB_Position_Paper.pdf> .

Rich in biodiversity, Bukit Brown is home to 66 species of birds, including those critically endangered; it also serves as a foraging site for the fauna of Singapore's Central Catchment Area; and a "sink" to absorb rainfall which recharges reservoirs and prevents flooding.

[27] Khiun Liew Kai, Natalie Pang and Brenda Chan, ‘New Media and New Politics with Old Cemeteries and Disused Railways: Advocacy goes Digital in Singapore’ (2013) 23 Asian Journal of Communication 605, 610-2.

[28] Tia Boon Sim, Bukit Brown Heritage Park (12 March 2012) Urban Sketchers <http://www.urbansketchers.org/2012/03/bukit-brown-heritage-park.html> .

[29] Terence Chong and Chua Ai Lin, ‘The Multiple Spaces of Bukit Brown’ in William Siew Wai Lim (ed), Public Space in Urban Asia (World Scientific, 2014) 27, 32-6; Kai and Pang, above n 24, 344-7; Lee, above n 2, 271; Ian Chong, Lisa Li, Erika Lim, Jennifer Teo and Woon Tien Wei, SOS Bukit Brown – Save Our Singapore (19 August 2014) SOS Bukit Brown <https://sosbukitbrown.wordpress.com>.

[30] Chong and Lin, above n 29, 28-32; Ong, above n 10, 232-6.

[31] Chong and Lin, above n 29, 39; Kai et al, above n 27, 606-7.

[32] Ler Seng Ann (URA Group Director Conservation & Development Services), Tough Decision in Face of Housing Needs Says URA (11 June 2011) The Straits Times <http://web.archive.org/web/20121001071619%20/http://www.ura.gov.sg/pr/forum/2011/forum11-06.html> .

[33] Yeoh and Huang, above n 3, 216.

[34] Huang and Yeoh, above n 7, 412; Kai and Pang, above n 24, 332; Sadowski, above n 4, 213.

[35] Huang and Yeoh, above n 7, 413.

[36] Yeoh and Huang, above n 3, 216.

[37] Huang and Yeoh, above n 7, 419; Ong, above n 10, 226-7; Brenda Yeoh and Lily Kong, ‘The Notion of Place in the Construction of History, Nostalgia and Heritage in Singapore’ (1996) 17 Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 52, 60-1.

[38] T.C. Chang and Shirlena Huang, ‘Recreating Place, Replacing Memory: Creative Destruction at the Singapore River’ (2005) 46 Asia Pacific Viewpoint 267, 268; see also J.E. Tunbridge, ‘Whose Heritage to Conserve? Cross-cultural Reflections on Political Dominance and Urban Heritage Conservation’ (1984) 28 Canadian Geographer 171, 174.

[39] Yeoh and Huang, above n 3, 201.

[40] Sim, above n 11, 401.

[41] Yeoh, above n 10, 111-3.

[42] T.C. Chang, ‘Place, Memory and Identity: Imagining ‘New Asia’ (2005) 46 Asia Pacific Viewpoint 247, 249; Henderson, above n 20, 547.

For an expanded discussion on this point, see: Maurizio Pelegii, ‘Consuming Colonial Nostalgia: The Monumentalisation of Historic Hotels in Urban South-East Asia’ (2005) 46 Asia Pacific Viewpoint 255.

[43] Yeoh and Kong, above n 13, 137-8.

[44] Deputy Prime Minster Goh Chok Tong, cited in Kelvin Low, ‘Concrete Memories and Sensory Pasts: Everyday Heritage and the Politics of Nationhood’ (2017) 90 Pacific Affairs 275, 281-2.

[45] Chang and Huang, above n 38, 271-4; Henderson 2011, above n 16, 56-8.

[46] Ong, above n 10, 229.

[47] Tia Boon Sim, A Very Long Sketch of Singapore River (16 September 2015) TiaStudio <http://tiastudio.blogspot.com/2015/09/a-very-long-sketch-of-singapore-river.html> .

[48] Henderson, above n 16, 48; Yeoh and Kong, above n 37, 61.

[49] Huang and Yeoh, above n 7, 417; David Tantow, ‘Politics of Heritage in Singapore’ (2012) 40 Indonesia and the Malay World 332, 337-9.

[50] Sanjukta Sen, Rediscovering Singapore through Urban Sketching (14 January 2016) Urban Sketchers <http://www.urbansketchers.org/2016/01/rediscovering-singapore-through-urban.html> .

[51] Chang, above n 14, 346.

[52] Chang and Huang, above n 38, 270-2.

[53] Yeoh and Huang, above n 3, 215.

[54] Tantow, above n 49, 340.

[55] Andrew Harding, ‘Five-foot Ways as an Embodiment of Public and Private Rights: The Origin, Survival and Preservation of Spatial Heritage in Singapore and Beyond’ (NUS Working Paper 2017/020, NUS Centre for Asian Legal Studies, October 2017) 8-9.

[56] Lesley-Anne Petrie, ‘An Inherently Exclusionary Regime: Heritage Law – the South Australian Experience’ [2005] MqLawJl 9; (2005) 5 Macquarie Law Journal 177, 180; Belinda Yuen, ‘Reclaiming Cultural Heritage in Singapore’ (2006) 41 Urban Affairs Review 830, 834.

[57] Kong, above n 8, 242; Yuen, above n 56, 837-8.

[58] Cai, above n 7, 121-3; Peggy Teo and Shirlena Huang ‘A Sense of Place in Public Housing: A Case Study of Pasir Ris Singapore’ (1996) 20 Habitat International 307, 315.

[59] Tia Boon Sim, Sketching an Old Estate in Singapore (2 March 2017) Urban Sketchers <http://www.urbansketchers.org/2017/03/sketching-old-estate-in-singapore.html> .

[60] National Heritage Board (NHB), The Singapore Heritage Plan (29 August 2017) National Heritage Board <https://www.oursgheritage.sg/what-is-the-heritage-plan-for-singapore/>, in particular sections on ‘our places’ and ‘our community’; National Heritage Board (NHB), Launch of Our Sg Heritage Plan – Singapore’s First Master Plan for the Heritage and Museum Sector (7 April 2018) National Heritage Board <https://www.nhb.gov.sg/~/media/nhb/files/media/releases/new%20releases/launch%20of%20our%20sg%20heritage%20plan%20at%20singapore%20heritage%20festival%202018%20-%207%20april.pdf>.

[61] National Heritage Board Act (Singapore, cap 196A, 1994 rev ed) s 5.

[62] Ibid ss 28-9.

[63] Ibid ss 6-7. Michael Koh (CEO, NHB and National Gallery), ‘Rooting for the Future: Views for the Heritage Sector in Singapore’ (2010) Southeast Asian Affairs 285, 290-2; National Heritage Board (NHB), About NHB (18 January 2018) National Heritage Board <https://www.nhb.gov.sg/who-we-are/about-us>.

[64] Preservation of Monuments Act (Singapore, cap 239, 2011 rev ed). Cai, above n 7, 105; Jack Tsen-Ta Lee, ‘We Built This City: Public Participation in Land Use Decisions in Singapore’ (2016) 10 Asian Journal of Comparative Law 213, 227.

[65] Preservation of Monuments Act (Singapore, cap 239, 2011 rev ed) ss 4, 11.

[66] Ibid ss 4-5, 11-8, 20-2.

[67] Ibid s 19.

[68] Urban Redevelopment Authority Act (Singapore, cap 340, 1990 rev ed) ss 18-9. Ministry of National Development, Our Agencies (3 March 2018) Ministry of National Development <https://www.mnd.gov.sg/about-us/our-organisation/our-agencies>.

[69] Urban Redevelopment Authority Act (Singapore, cap 340, 1990 rev ed) ss 6-7, 12, 15.

[70] Planning Act (Singapore, cap 232, 1998 rev ed) ss 6-8, 10. Cai, above n 7, 95-7; Lee, above n 64, 217; Yuen, above n 56, 838; Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), 2014 Master Plan – Identity – Safeguarding Out Built Heritage and Identity Nodes (31 October 2018) Urban Redevelopment Authority <https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Planning/Master-Plan/Key-Focuses/Identity/Built-Heritage-and-Identity%20Nodes>.

Note that while another of the URA’s core roles is to be the government land transaction agent, meaning it is an agency actively involved in land acquisitions, the interaction between heritage laws discussed and the Land Acquisition Act 1966 fall outside the scope of this paper.

[71] Planning Act (Singapore, cap 232, 1998 rev ed) pt 3. Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), Apply for Planning Permission (31 October 2018) Urban Redevelopment Authority <https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Guidelines/Development-Control/Planning-Permission>.

[72] Planning Act (Singapore, cap 232, 1998 rev ed) s 9. Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), Conservation Areas (31 October 2018) Urban Redevelopment Authority <https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Get-Involved/Conserve-Built-Heritage/Explore-Our-Built-Heritage/Conservation-Areas/>.

[73] Planning Act (Singapore, cap 232, 1998 rev ed) s 11. Cai, above n 7, 109-11; Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), Guidelines – Conservation (31 October 2018) Urban Redevelopment Authority <https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Guidelines/Conservation/>.

[74] Preservation of Monuments Act (Singapore, cap 239, 2011 rev ed) ss 4, 11; Planning Act (Singapore, cap 232, 1998 rev ed) s 9.

[75] Lee, above n 2, 269.

[76] See above Section I.

[77] Dimery, above n 4, 210; Ong, above n 10, 347; Petrie, above n 56, 177-9; Tunbridge, above n 38, 172.

[78] Teoh Yi Chie, Rochor Centre Sketches (27 February 2016) Urban Sketchers <http://www.urbansketchers.org/2016/02/rochor-centre-sketches-feb-2016.html> .

[79] Planning Act (Singapore, cap 232, 1998 rev ed) pt 3. Lee, above n 2, 269.

[80] Dimery, above n 4.

[81] Tia Boon Sim, Public Housing (31 May 2009) Urban Sketchers <http://www.urbansketchers.org/2009/05/public-housing.html> .

[82] Planning Act (Singapore, cap 232, 1998 rev ed) ss 2-3, 13.

[83] Preservation of Monuments Act (Singapore, cap 239, 2011 rev ed) s 11(7). Lee, above n 64, 227-8.

[84] Lee, above n 64, 221-3, 228-30; Thio Li-ann, ‘The Theory and Practice of Judicial Review of Administrative Action in Singapore’ (Paper presented at SAL Conference 2011, Singapore, 24-25 February 2011).

[85] Tia Boon Sim, Soon it will be History (30 March 2017) Urban Sketchers <http://www.urbansketchers.org/2017/03/soon-it-will-be-history.html> .

[86] Dimery, above n 4, 203; Fincham, above n 4, 646.

[87] Fincham, above n 4, 647.

[88] Sadowski, above n 4, 223.

[89] Fincham, above n 4, 663-4.

[90] Don Low, The Last Kampong in Singapore (23 October 2010) Urban Sketchers <http://www.urbansketchers.org/2010/10/last-kampong-in-singapore.html> .

[91] National Heritage Board (NHB), NHB Embarks on Nation-wide Survey of Tangible Heritage (6 May 2015) National Heritage Board <https://www.nhb.gov.sg/~/media/nhb/files/media/releases/new%20releases/2015-9.pdf>; Melody Zaccheus, Nationwide Survey to get Better Grasp of Singapore's Heritage (15 March 2015) The Straits Times (re-published on Asia One) <http://www.asiaone.com/singapore/nationwide-survey-get-better-grasp-singapores-heritage> .

[92] Carys E. Jones and Paul Slinn, ‘Cultural heritage in EIA – Reflections on Practice in North Western Europe’ (2008) 10 Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management 215; Patrick R. Patiwael, Peter Groote and Frank Vanclay, ‘Improving Heritage Impact Assessment: An Analytical Critique of the ICOMOS Guidelines’ (2018) 24 International Journal of Heritage Studies 1; Petrie, above n 56, 197-8; Ana Pereira Roders, ‘Guidance on Heritage Impact Assessments’ (2012) 2 Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 104.

[93] Antiquities and Monuments Office, Heritage Impact Assessment (31 July 2018) Antiquities and Monuments Office <https://www.amo.gov.hk/en/hia_01.php>; Commissioner for Heritage’s Office, Heritage Impact Assessment (23 December 2016) Development Bureau <https://www.heritage.gov.hk/en/impact/index.htm>. David Lung, ‘Built Heritage in Transition: A Critique of Hong Kong's Conservation Movement and the Antiquities and Monuments Ordinance’ (2012) 42 Hong Kong Law Journal 121, 128; Ayesha Pamela Rogers, ‘Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment: Making the Most of the Methodology’ (Paper presented at International Conference on Heritage Conservation, Hong Kong, 12-13 December 2011) <http://www.heritage.gov.hk/conference2011/en/pdf/paper/dr_ayesha_pamela_rogers.pdf> .

[94] Koh, above n 63, 290-2.

[95] National Heritage Board (NHB), The Singapore Heritage Plan – Our Places (29 August 2017) National Heritage Board <https://www.oursgheritage.sg/what-is-the-heritage-plan-for-singapore/our-places/>.

[96] Don Low, Sketching Singapore's Heritage: Ellison Building (7 September 2016) Urban Sketchers <http://www.urbansketchers.org/2016/09/sketching-singapores-heritage-ellison.html> .

[97] See above Section I B 1.

[98] Petrie, above n 56, 185-6.

[99] Planning (Master Plan) Rules (Singapore, cap 232, s 10, 2000 rev ed) ss 4-5.

[100] Tia Boom Sim (artist), Time Out Singapore: My Queenstown Festival Preview (21 September 2013) Gwen Pew <https://gwenpew.com/2013/09/21/tos-my-queenstown-festival-feature/>.

[101] Fincham, above n 4, 644-5, 652-5.

[102] Lim, above n 26, 241.

[103] Marcus Binney and David Lowenthal, Our Past Before Us: Why Do We Save It? (Blackwell Press, 1981) 17.

[104] James Fitch (conservation practitioner) quoted in Lung, above n 93, 133. For a discussion of the practical challenges tied to participation, see: Minoushka Lush, ‘Built Heritage Management: An Australian Perspective’ (2008) 15 International Journal of Cultural Property 65; Esther H.K. Yung and Edwin H.W. Chan, ‘Problem Issues of Public Participation in Built-Heritage Conservation: Two Controversial Cases in Hong Kong’ (2011) 35 Habitat International 457.

[105] Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas, International Council on Monuments and Sites, opened for signature 1987 (entered into force 1987) art 3.

[106] Kong, above n 8, 250.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJlStuS/2019/5.html