|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal Student Series |

INSOLVENCY AND ILLEGAL PHOENIX ACTIVITY IN THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CURRENT MEASURES IN PLACE AND POTENTIAL FOR LAW REFORM

TRISHA HASSAN

ABSTRACT

Insolvency and illegal phoenix activity in the Australian construction industry has been a prevalent issue for decades and the problem only continues to grow. The multitude of government reports, inquiries and investigations have not seen a significant breakthrough in the elimination or reduction of this type of activity, thus costing the Australian economy billions of dollars every year. It is the aim of this paper to identify the key issues the construction industry faces which make it susceptible to illegal phoenix activity and to offer recommendation of appropriate policy reforms directed to this specific problem. The Federal Government has, indeed, recently gone to significant measures in an attempt to generally contain the problem of illegal phoenixing, but focus must now shift to enforcement and consideration of past recommendations gone unnoticed. Going forward, the solution calls for a multi-pronged approach which includes more effective enforcement of current laws.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Illegal phoenix activity has been a significant issue in the construction industry for decades and continues to be one of the main reasons behind the failure of businesses in this sector of the economy. According to a report published by PricewaterhouseCoopers Consulting (PwC) on behalf of the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) in July 2018, illegal phoenixing costs the Australian economy from $2.85 to $5.13 billion each year (including unpaid creditors, unpaid employee entitlements and unpaid taxes/compliance costs).[1] Of this amount, $1.16 to $3.17 billion was owed to trade creditors alone. It was stated in a 2012 Inquiry by Bruce Collins QC that “the flight of the phoenix is prevalent in the building and construction industry in NSW”[2] and the problem continues to grow. In this same report, it was found that 24.7% of NSW insolvencies could be attributed to the construction industry, with only the ‘other financial services’ sector having a larger portion.[3] According to the report, by the end of 2012, businesses within the construction industry in NSW owed over $400 million to unsecured creditors, with this number rising yearly.[4]

There have been multiple investigations into phoenix activity, especially within the construction industry including the 2003 Cole Report[5], 2004 Parliamentary Joint Committee report[6], and the 2012 Collins Inquiry.[7] The most recent endeavours to address the problem has come in the form of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Combatting Illegal Phoenixing) Act,[8] and the Treasury Laws Amendment (Registries Modernisation and Other Measures) Act[9].

While these new legislative measures are a step in the right direction and are indeed welcomed, they have fallen short as a comprehensive solution to the problem of illegal phoenixing and have been met with criticism.[10] Although the new measures provide an added layer of protection against illegal phoenix activity, it has not addressed the undercapitalisation problem in the construction and building sector. As will be analysed further, undercapitalisation is a large factor in the failure of businesses in the construction industry and, as noted by the corporate regulator, more care needs to be taken when incorporating businesses, especially in the building and construction industry.[11]It is clear that the Australian government has recently gone to significant measures in an attempt to contain the occurrence of illegal phoenix activity, but these issues impacting the construction and building sector persist.[12]

This thesis aims to analyse the current measures in place to combat illegal phoenixing and to provide recommendations for potential law reform with particular reference to these problems in the construction and building sector. Chapter 1 will define illegal phoenix activity, arising from insolvency, as well as provide recent general facts and figures concerning the scale of the problem. This chapter will draw attention to the wide scale of the issue, extracting data from the 2015 Parliamentary inquiry to affirm that the matter remains relevant despite the conduct of a multitude of reports and inquiries into this problem. This chapter will discuss how illegal phoenix activity affects the economy generally.

Chapter 2 will expand on this issue, but regarding the specific problems faced in the construction and building industry which make it so susceptible to insolvency and illegal phoenix activity. This chapter will provide a detailed explanation of the key factors which are very influential in construction businesses which makes illegal phoenix activity more prevalent in this sector of the economy. The factors include a large number of unsecured trade creditors, the prevalence of poor payment practices, and sizeable incidence of undercapitalisation and how all of these factors may contribute to insolvency and illegal phoenixing.

Chapter 3 will discuss the current measures in place to combat illegal phoenix activity, with express reference to the recently introduced Treasury Laws Amendment (Combatting Illegal Phoenixing) Act. This Chapter will discuss the statutory amendments introduced to combat illegal asset transfers and the avoidance of tax liabilities. This Chapter will also discuss the policy consideration behind the proposed introduction of the Director Identification Number (DIN)[13] as well as its potential benefits in seeking to stamp out illegal phoenix activities.

Chapter 4 will analyse the current legal framework with reference to both the positive features and drawbacks of the current legal framework to combat illegal phoenixing activities. Additionally, this chapter will draw attention to the current gaps which exist in the regulatory environment.

Building on this critique, Chapter 5 will explore and offer recommended solutions for consideration to combat illegal phoenixing activities in the construction and building sector. The law reform solutions offered will be tailored specifically to address the illegal phoenixing problems in this key sector of the economy. Possible solutions include the introduction of minimum capital requirements to combat the problem of undercapitalisation; the introduction of a national Security of Payment (SOP) Act to ensure clarity around this legislation. It would be beneficial to introduce a national SOP Act as, currently, these Acts remain state-based and therefore may cause confusion to subcontractors or other parties intending to rely on the system according to the Senate Economics Reference Committee.[14] Further law reform measures could include restricted directorships to protect creditors against directors with a history of corporate failure while also allowing these directors education opportunities.

A beneficial owners’ register is also suggested to allow for further transparency in ASIC’s registers due to the abundance of false information currently seen. A call is made for training programs for directors to be a potential avenue for capacity building in management practices. Management education among managers and directors in construction companies falls far below what should be required in terms of sound business management, as illustrated in Chapter 5. Flatter business structures should also be explored as a way to minimise the impacts of defaults of large Tier 1 companies often seen in the traditional pyramid structure in the construction industry. That is, allow for less hierarchical business structures in the industry so the failure of larger companies does not cause such a destructive ripple effect. The discussion in Chapter 5 will highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each solution proposed to provide an objective view of each suggestion. Chapter 6 concludes with reasons for the preferred solutions to combat illegal phoenixing in the construction industry and with recommendations for further law reform to bridge the current gap in the regulatory regime.

Phoenix activity, especially what constitutes illegal phoenixing, has always been an elusive concept which continues to present challenges. This chapter will offer key definitions of phoenix activity and explanations for relevant sections of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) which may impact illegal phoenix activity. The various types of phoenix activity will be analysed to demonstrate the difficulty regulators may have in determining what exactly may classify as illegal conduct. Additionally, this chapter will draw attention to the phoenixing problem in the construction and building industry, as well as the Australian economy in general, with express reference to the 2015 Parliamentary inquiry, with a specific focus on the significant submissions made by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) and Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) to this important inquiry.

Phoenixing in general can be defined as a new company ‘arising from the ashes’ of its unsuccessful predecessor.[15] Generally, the controllers of the former failed company transfer business to the new company whilst leaving liabilities and debts behind.[16] However, not all phoenix activity is illegal and such transfers may make economic sense in some cases. According to the Australian Law Reform Commission, restructuring may be beneficial through the preservation of jobs, provision of some return to creditors, and encouragement of innovation.[17] Anderson et al define legal phoenix activity as when controllers start another similar operation in an attempt to rescue their previous business.[18] An issue arises when controllers begin to abuse this concept to engage in unlawful activities. This distinction, between legal and illegal phoenix activity, is difficult to define but will be explored in this chapter.

To truly explore illegal phoenix activity, the concept of insolvency and the nature of directors’ duties must first be addressed as insolvency constitutes the cornerstone of fraudulent phoenix activity. This is because phoenixing occurs when a business becomes unable to pay its debts and decides to wind up only to create a similar business without the debt of the former company.[19] Of course, this creates a multitude of issues for creditors, employees, and taxation authorities.[20] According to s95A of the Corporations Act 2001, insolvency occurs when a business becomes unable to pay its debts as and when they become due and payable. Insolvency is generally measured through a cash flow test by assessing whether a company’s cash flows will allow for payment of current and future liabilities as they are due.[21] This legal test, however, is not always easy to apply and a company may trade in and out insolvency. Insolvent companies are regulated under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and administered by insolvency practitioners with oversight by ASIC.

The Corporations Act provides for many types of external administration, such as liquidation, voluntary administration, or receivership.[22] If a company is incapable of rescue, it will be liquidated, and the company stops trading. Typically, the company is deregistered thereafter bringing its existence to an end. Liquidation may occur in one of two forms – voluntary liquidation, where shareholders or creditors decide to liquidate the company, or court-ordered liquidation, where a liquidator is appointed by the courts upon application, usually by a creditor.[23] The liquidator aims to wind up the company in a way that will provide the greatest benefit to creditors.[24] As explored further within this paper, construction companies that enter liquidation tend to be unable to pay back a majority of creditors the full amount they are owed, thus demonstrating the need for insolvency issues to be caught early on.[25]

Now that the concept of insolvency and process of liquidation have been briefly explained, it is relevant to explore how directors’ duties tie into it all and can impact law enforcement and accountability for illegal phoenix activity. s588G of the Corporations Act is important here and is designed to impose personal liability on directors (and not officers) for insolvent trading. Section 588G states that directors must not knowingly or unknowingly engage in insolvent trading or in any activity which may cause their business to become insolvent to protect creditor interests. If it is found that a director has breached this duty, the court may order a compensation order, pecuniary penalty order, disqualification, or a combination of the three under the civil liability provisions in s588G(2).[26] If it is found that the director has committed a criminal offence per s588G(3), they may incur a fine or be sentenced to imprisonment for up to five years.[27]

Defences are available for allegations regarding breach of s588G which mainly center around the belief that incurrence of the debt at the time would not push the company into insolvency – an important concept to keep in mind when discussing illegal phoenix activity.[28] S588G aims to protect creditors from directors who may expose the company to unnecessary financial risk while they are protected by limited liability.[29] According to ASIC, there are four key principles directors should consider when performing their role.[30] They must remain informed regarding their company’s financial position and ignorance will not be considered a defence for falling into insolvency.[31] Directors should also investigate the cause of financial difficulties within the company and obtain the advice of a qualified professional when necessary.[32] Once this advice is obtained, they should act appropriately to ensure the company remains financially viable.[33]

Besides s 588G, there are other relevant statutory provisions under the Corporations Act which can be relied upon by ASIC to pursue directors and officers who have engaged in improper phoenix activity. Sections 180-183 of the Act prohibit directors and officers, from acting in a manner that would negatively impact the company to create personal gain.[34] Section 180 covers the duty of care and diligence as well as the business judgement rule, which provides that a director is said to have met the requirements of s180(1) if they make a business decision in good faith and believe the decision is in the best interests of the business.[35] Section 181 also provides that directors must act in “good faith in the best interests of the corporation”.[36] Section 182 states that a director must not improperly use their position to attain any personal advantage or cause damage to the company and s183 expands upon this, mentioning that information obtained through directorship must not be used improperly to gain personal advantage or cause detriment to the corporation.[37]

For example, turning to case law, in Jeffree v National Companies and Securities Commission[38], it was found that a director of the corporation had improperly used his position to authorise the transfer of assets to a newly formed company to defeat claims against the former company, thus contravening s182.[39] Additionally, Australian Securities Investments Commission v Sommerville[40] demonstrates that advisors may also become liable if they assist a company and directors with engaging in illegal phoenix activity. This case involved a solicitor who advised directors to transfer assets to new companies with similar names and operations whenever there was a threat of insolvency – thus advising those directors to engage in phoenix behaviour.[41] These concepts must be fully appreciated before the phoenixing problem can be addressed as these sections form the basics of why this type of activity may be illegal in certain circumstances.

Not all business recovery activity is fraudulent and therefore a line must be drawn between legal and illegal phoenix activity. This may be difficult to determine, however, as business operators may go to extensive lengths to mask their illegal phoenix activities as genuine business recovery operations.

The distinction between legal and illegal phoenixing is when the controllers intend to exploit the corporate form, thus harming unsecured creditors, employees, and the government, usually in the form of tax authorities.[42] In a 2018 report analysing the economic repercussions of illegal phoenix activity, PricewaterhouseCoopers Consulting stated that illegal phoenix activity can be identified as “deliberate and systematic liquidation of a corporate trading entity which occurs with the intention to avoid tax and other liabilities”.[43] The Australian Law Reform Commission also stated in 2019 that a cornerstone of illegal phoenix activity is the abuse of limited liability and legal availabilities for corporate restructures in the case of genuine failure.[44]

Finding a concise definition of the concept of illegal phoenix activity is a difficult task. There are a variety of categories of phoenix activity which make the distinction slightly clearer, but these groups tend to blend into each other, as discussed below.

There are five general categories into which most phoenix companies fall.[45] Firstly, there is the legal phoenix otherwise known as business rescue where a company fails, and resources are utilised in an attempt to save the company from failure to continue operations as normal.[46] In these cases, there is no intention to commit fraud but some creditors may not receive what they are owed, as is the case with any legitimate business failure and the creditor should accept this risk.[47] The second category is comprised of ‘problematic phoenixes’, where there is not necessarily malicious intent but an underqualified or hapless director does not take the required precautions to protect the business.[48] It is mentioned that, in these cases, it is not beneficial to creditors or society to resurrect the company and therefore results in a waste of resources as the business should be left to cease operations.[49]

The categories then move into illegal territory. Category 3 contains companies that have directors who have the intention to exploit the system by transferring assets to the new company at undervalue.[50] This tends to occur as the former company approaches insolvency. The second illegal type, category 4, is ‘phoenix as business model’, where directors create companies with the sole intention of phoenixing to exploit the systems in place to assist with genuine business failures.[51] The company was never intended to be successful and the actual business of the company is to ‘separat[e] the business from its obligations’.[52] Finally, category 5 – ‘complex illegal phoenix activity’ – relates to companies which have the characteristics of those companies in category 4, but also engage in other illegal conduct such ‘use of false invoices, GST fraud and money laundering’.[53]

It is important to note that genuine business failure is never illegal – failure is only classified as illegal phoenixing when the intention to exploit the system by not paying creditors and continuing operations through a new entity is present.[54] This is where the difficulty arises in determining what constitutes illegal phoenix activity, as conduct may closely resemble steps taken in a genuine business restructure. According to the PwC report, the intention creates the distinction between legal and illegal business restructures.[55]

According to Chapter 2 of the 2015 Parliamentary Joint Committee Inquiry into insolvency in the construction industry, construction companies ‘face an unacceptably high risk of entering into insolvency’ or at least fall victim to an insolvent business ‘further up in the contracting chain’.[56]

As mentioned previously, PwC reported that illegal phoenix activity resulted in an economic impact of up to $5.13 billion in the 2015-16 tax year. It is important to note that these figures do not directly relate to the construction industry, but it comprises a large portion. The costs were broken down into three categories: unpaid trade creditors, unpaid employee entitlements, and unpaid taxes/compliance costs.[57] It was found that GDP, household consumption, and government revenue are all negatively impacted by illegal phoenix activity.[58]

Furthermore, PwC reported that Australian GDP was impacted by as much as $3.46 billion by phoenix activity in the 2015-16 year as a result of the inefficient use of resources and reduction of spending patterns in Australia.[59] This is explained by the fact that goods and services may be purchased by consumers but will not necessarily be delivered – thus acting as a sort of tax on customers.[60]

On 4th December 2014, the government launched a Parliamentary Inquiry into insolvency in the Australian construction industry to gather information on why insolvency is such a large problem facing these businesses. This inquiry contained submissions from 31 separate sources including the ATO (submission 5), ASIC (submission 11), and various associations concerning insolvency in the construction industry. The submissions detail what constitutes legal and illegal phoenix activity whilst providing recommendations to address potential phoenix risk.

The ATO submission flagged phoenix activity as a large problem. The submission stated that the industry lends itself to significant construction chains pressure and tight terms of trade,[61] with businesses paying bills on an average of 53 days rather than the standard 30-day term.[62] Furthermore, it was found that 34% of businesses had customers or suppliers who became insolvent and therefore could not pay their bills in 2015.[63]

It was also reported that, of businesses in the building and construction industry, over 50% were in debt to the ATO.[64] Furthermore, the level of voluntary payment of activity statement and income tax obligations stood at 81% and 44% respectively. It was also reported that building and construction taxpayers took, on average, 360 days to achieve 95% payment of liabilities due whereas other taxpayers took approximately 90 days.[65]

The ASIC Report documented amounts owing to secured and unsecured creditors of construction industry insolvencies, with 19.3% of companies owing up to $500,000 to secured creditors and 72.7% owing to unsecured creditors from a sample size of 10,394 companies from 2010-2014.[66] ASIC also reported that 80.3% of these companies owed up to $250,000 in unpaid tax liabilities.

The ASIC Report also recognised causes of failure for construction companies, with some major factors being undercapitalisation, poor financial control, and inadequate cash flow or high cash use.[67] These issues all revolved around the handling of financial assets and, with adequate capital reserves, these companies may be able to sustain operations even during difficult economic periods without becoming insolvent.

ASIC’s submission discusses phoenix activity in construction companies and marks this as a large issue. It is mentioned that this is an inevitable side effect of the concept of separate legal entity and should only be considered an issue when it is conducted illegally.[68] Illegal activity arises when there is an abuse of the corporate form to “intentionally deny creditors of their entitlements”.[69] This essentially results in a possible breach of directors’ duties per the Corporations Act 2001 ss180-184 and/or 590.[70]

ASIC referred to the Cole Royal Commission into the Building and Construction Industry of 2003[71], where it was found that there was a significant amount of fraudulent phoenix activity in the industry. These results were found to be in line with ASIC’s external administrator reports from 2010 to 2014, where it was shown that allegations of misconduct by breach of ss180-184, 588G, and 590 of the Corporations Act were considerably higher in the construction industry as opposed to others. ASIC also drew upon the PwC figures mentioned in the ATO report to communicate the cost illegal phoenix activity had on the government.[72]

ASIC’s initiatives to lessen phoenix activity in general were also listed, including a statutory declaration campaign for the construction industry, proactive phoenix surveillance programs, and administration of the Assetless Administration Fund.[73] This Fund aims to finance preliminary investigations into companies that have established themselves with insufficient assets.[74]

It was agreed in the final report that increased transparency of directors would be beneficial in decreasing phoenix activity. Two suggestions supported by the Committee were the introduction of a beneficial owners’ register and Director Identification Numbers (DIN). The DIN has been introduced and will be discussed in Chapter 3. Submission 14 from Veda Advantage, a credit reference agency, proposed a beneficial owners’ register which would record both the controllers of a company as well as the beneficial owner.[75] This would assist in revealing who actually controls an entity, thus “making money laundering, tax evasion and the creation of phoenix entities more difficult”.[76] This register should be available to the public or, at least, law enforcement and tax authorities.[77]

In September 2017, the Treasury released a report entitled “Combatting Illegal Phoenixing” in an attempt to receive feedback to assist with the Government’s next round of insolvency law reforms.[78] Part two of the report addresses higher risk entities, stating ‘there are presently no special compliance measures applied to entities or individuals who present a high risk of engaging in illegal phoenix activity’ and that this is something the government must take into concern.[79] Examples are provided, such as the self-assessment tax method whereby individuals and entities are trusted to comply voluntarily until investigations ensue, thus allowing exploitation of the system.[80] Furthermore, repeat phoenix offenders continue to be allowed the benefit of the doubt by being able to appoint their own liquidator, receive tax refunds whilst overdue tax forms giving rise to liabilities remain overdue, and exploit the 21 day notice period under the Director Penalty Notice to unlawfully dispose of or transfer assets to a new company.[81] The ATO’s Phoenix Taskforce has identified cases where companies have created a relationship with specific liquidators, thus weakening their objectivity and harming creditor interests.[82] To address this problem, the Treasury recommended a cab rank model for appointing liquidators rather than allowing the company to choose.[83]

The facts and figures above demonstrate that illegal phoenix activity is still a prevalent issue. This remains the case even though there has been a multitude of inquiries and reforms put forward. Attention is now turned to the question as to why is illegal phoenixing a particular problem in the construction and building industry. Chapter 2 addresses this issue seen in Australia with specific reference to the unique factors businesses in the construction industry face. Further reforms introduced in 2020 to tackle the problem will be discussed in Chapter 3.

This chapter analyses the specific problems the construction and building industry faces which makes it so prone to illegal phoenix activity. The industry is unique in the way it operates as it is project-based, and these projects tend to be on a large scale. This chapter will also examine the major common factors present in construction companies which reveal the difficulties faced and thus lead to the disproportional levels of insolvency seen in the industry.

Although illegal phoenix activity is a prevalent issue among many sectors, it is clear that this type of activity pervades the construction industry due to its hierarchical, credit reliant nature.[84] It will be important to discuss the specific problems which pervade the construction industry to understand the underlying reasons for illegal phoenix activity before suggestions can be made to target it. In the 2015 Senate report, it was stated that, although the construction industry had only contributed from 8-10 percent of national GDP and employment from 2005-2015, it had accounted for between 20-25 percent of all insolvencies in Australia in the same period.[85] The committee reported that, although the construction industry is naturally competitive, there are larger, more powerful factors such as imbalances of power within contracts and unconscionable conduct which contribute to the vast amount of insolvencies that can be seen.[86]

The Committee flagged two major problems for businesses within the construction industry – structural issues and phoenixing. It is explained that, due to the large jobs undertaken by construction companies, head contractors will generally enter into agreements with developers and then align with subcontractors to engage with the tangible work. However, again, due to the overwhelming nature of the tasks, these subcontractors may employ more subcontractors who may then hire even more.[87] It will be important to propose a solution to protect subcontractors. With regards to phoenixing, the Committee was of the view that, although there had been numerous inquiries and recommendations, phoenix activity within the construction industry and in the economy in general remained far too high.[88] Attention has been placed on identifying phoenix activity for years with no real reforms put in place and loopholes remain open.[89] In NSW from 2017-18, ASIC received 1642 reports of corporate insolvency in construction companies[90] and administrators found evidence of wrongdoing in 561 companies.[91]

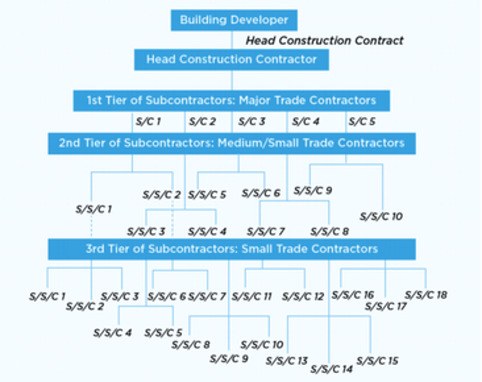

Coggins, Teng, and Rameezdeen outline the major elements that are present in construction companies which make them prone to insolvency and, by extension, phoenix activity.[92] The first element is the intrinsic pyramidal structure of contracting chains. The figure below provides a visual representation of the vast number of subcontractors in place for most projects.[93] The issue becomes apparent when it is realised that the collapse of any tier will result in financial burden for those below. It is mentioned that Tier 4 contractors may be “small one-person sole trader firms”[94], with burdens such as the collapse of Tier 1 or 2 firms being enough to cause severe distress to their livelihoods. The contractors at the bottom of the chain are at the greatest risk of a client or contractor defaulting and, unfortunately, these lower-level subcontractors are the parties who will suffer most as a result of the fiscal strain left by these larger corporations.[95]

In Chapter 6 of the 2015 parliamentary inquiry report, the words of Mr Graham Cohen are cited to reiterate the negative repercussions this pyramid structure may have: ‘for every failure on the big end of town there are a multitude of small house-type builders who go to the wall’.[96] This chapter also contains analysis of one of the largest collapses in the construction industry, that of Walton Constructions. This collapse occurred due to insolvent trading and concerns were raised regarding related party duties and responsibilities. It was mentioned that, as Walton was such a large corporation, that the Queensland regulator, QBCC, may have allowed the company preferential treatment and been negligent in providing a license without taking the necessary steps to evaluate whether this would be a sound decision.[97] As a result, the Committee was of the view that all regulators should take more care in ensuring the financial stability of a corporation before offering a license.

This section will also briefly examine the negative impacts the collapse had on smaller subcontractors to demonstrate the disastrous effects the failure of large corporations may have on the livelihoods of workers. The full effects of the collapse of Tier 1 companies should be understood to express to banks or regulatory bodies that greater care must be taken when offering licenses to large corporations with the ability to destroy all subcontractors below them. According to the submission made to the inquiry by the Subcontractors’ Alliance, at the time of collapse Walton Constructions owed 1350 subcontractors over $70 million.[98] Furthermore, there is evidence that Walton had applied for 4 extensions (which were all approved) from the Queensland building authority to provide financial information to support the building license.[99] This brings into question whether or not the building authority had conducted their due diligence in issuing a building license and reiterates the need for authorities to conduct the necessary checks for financial viability prior to issuing licenses. The Committee heard one case where a subcontractor lost $2.5 million and two businesses as a result of the Walton collapse.[100] The subcontractor then went into liquidation himself and the breakdown of his businesses resulted in the loss of employment for his workers, highlighting the flow-on effects of the default of large corporations in the industry.[101] It was recommended by the committee that regulators should conduct random spot checks to ensure the financial health of a license holder in an attempt to prevent similar occurrences.[102]

Another reason for insolvency is the predominance of trade credit in the industry.[103] According to a UK study published by Ive and Murray, firms in the construction industry tend to rely on credit from suppliers more than the rest of the economy.[104] Furthermore, in the 2012 Collins Inquiry, it was found that average payment terms between contractors and subcontractors ranged from 45-80 days, sometimes extending to 90-120 days.[105] It is important to note that the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1999 (NSW) was introduced subsequent to this report.[106] The SOP Acts will be discussed further in Chapter 5. As a result of these credit terms, construction businesses tend to face cash flow issues that negatively impact subcontractors, with those at the bottom of the chain bearing the full extent of the problem.

Unsecured creditors also create a large portion of the problem. Secured creditors generally retain title claims or interest over equipment provided and preferential creditors receive funds from liquidation proceedings should the company become insolvent.[107] However, unsecured creditors have no such claim and therefore suffer the most when a company is put into liquidation. According to s556 of the Corporations Act, payments in liquidation proceedings must be allocated in the following order – money owed to secured creditors, expenses and fees of the liquidator, remaining wages and superannuation expenses relating to employees, and finally unsecured creditors. When leftover funds are not enough to repay unsecured creditors fully, companies must distribute the proceeds on a pro-rata basis, therefore leaving unsecured creditors with a much lower return than expected, oftentimes not recouping their initial investment at all.[108]

In a study conducted in New Zealand by Ramachandra and Rotimi, construction companies were broken down into three categories – general construction, property developers, and construction trade services. They observed that general construction businesses had the largest amount owing to trade creditors and, when these companies went into liquidation, 37% owed between $100,000 to $500,000 to creditors, with an additional 30% owing less than $100,000.[109] With regards to construction trade services, 56% of companies owed creditors less than $100,000 in liquidation and a further breakdown showed that 67% of this 56% owed between $50,000 and $100,000.[110]

Additional analysis was conducted to ascertain whether these companies upheld their duties to unsecured creditors post-liquidation. No companies within the general construction category were able to pay their creditors after liquidation proceedings.[111] Property developers were able to pay one in 22 creditors 11.89 cents per dollar but could not pay a staggering 77% of its creditors at all.[112] The remainder of the companies in this category either did not have creditors or did not disclose the amounts owed. Furthermore, it was found that, in construction trade services, only one in every sixteen companies paid trade creditors fully, approximately 20% paid pro-rata at a rate of 20 cents per dollar and 75% could not pay their trade creditors at all.[113] Of course, as these figures have been extracted from a New Zealand study, it cannot be said that they directly correlate to the Australian construction environment but the statistics cannot be far off as the New Zealand and Australian construction industries are grouped in many analytical reports.[114]

In a separate article published by Ramachandra and Rotimi in 2014, a study of litigations in the New Zealand construction industry was conducted to gain an insight into payment disputes, with possible solutions suggested to assist with mitigation of these problems.[115] As mentioned above, the chain structure of the construction industry raises issues which cause a domino effect, negatively impacting those at the bottom of the pyramid the most. Odeyinka and Kaka mention that, in a variety of cases, the bank fails to support the developer, who then fails to support the head contractor, who then fails to support their direct subcontractor, and so forth.[116] As subcontractors at the lower end of the chain are unable to bear the financial burden, they incur additional costs in trying to secure cash from other sources, thus further increasing risks of insolvency.[117] Suggestions regarding provisions to assist with non-payment may be considered a solution but it is also mentioned that, although provisions already exist to assist with payment procedures, problems tend to arise due to deliberate noncompliance.[118]

Poor payment practices have existed in the construction industry for decades, with many inquiries and reviews conducted in an attempt to remedy the problem.[119] It is mentioned that, in the 1990s, clauses were introduced into standard building contracts stipulating that, for a contractor to be paid, they must prove that they have paid their subcontractors any money owed.[120] However, as the Collins inquiry revealed, many head contractors submitted false statutory declarations stating that their subcontractors had indeed been paid.[121] The report stated that, although the submission of false statutory declarations is an offence under the Oaths Act 1900 and is punishable by up to seven years imprisonment, a major reason as to why this type of activity runs rampant is that it is not policed.[122] Furthermore, it was found that, in some cases, subcontractors had been coerced into signing false declarations on promises that they would be paid soon after as long as they agreed that they had already been paid.[123] They were also told that delayed payment was simply an element of the job and that they would have to accept delayed payment for the job at hand if they wished to be paid for any future work.[124]

Additionally, it was found that no laws stipulated what must be done with funds received by head contractors until the funds become due to subcontractors. In some cases, funds were used for discretionary spending whereas in other cases funds were used to pay for previous projects.[125] Essentially, it is this power imbalance between head contractors and subcontractors which leads to poor payment practices across the industry as those parties lower down the contracting chain are unable to seek the legal action they require due to lack of resources or fear of losing work. Subcontractors are often viewed as ‘disposable’ by head contractors if they are not specialists in the field and therefore if they are unable to provide labour as expected, they may easily be switched out.[126] As the industry is so competitive, especially in the space of projects less than $10 million, head contractors can easily exploit subcontractors as they fear that they will lose future work opportunities if they do not comply with the head contractor’s demands.[127]

As mentioned previously, undercapitalisation also constitutes a major reason as to why so many businesses in the industry fail. The ASIC inquiry submission flagged that in 2013/14 435 construction firms failed due to undercapitalisation being a factor,[128] representing 20% of external administrator reports for the year.[129] Furthermore, it is reported that, due to the nature of the industry, the equipment required tends to be available for short-term hire and therefore businesses can run without an injection of a sufficient amount of capital to stay afloat.[130] Therefore, construction businesses tend to rely solely on cash flow or generous credit terms but when pressure increases, a firm cannot sustain itself without sufficient capital to fall back on.[131] A potential solution to remedy this problem would be to implement minimum capital rules. This would assist in combatting illegal phoenixing as companies could not be incorporated on a whim to avoid debts and would assist with cash flow problems in cases of emergency. This recommendation will be explored further in Chapter 5.

The final factor that Coggins et al suggest as a reason for construction insolvency is that of poor business management skills, which was also raised in the ASIC submission as a major issue.[132] In 2013/14, it was reported by external administrators that over 40% of failures in the industry could be attributed in part to poor strategic business decisions and an additional 46% of defaults flagged poor management of accounts receivable or lack of reports as a major cause of failure.[133] The Master Builders Australia submission states that, although apprentices are taught thoroughly about the hands-on aspects of the job, they do not undergo the necessary training to handle management decisions.[134] It can be seen that a large part of the problem lies in the management of these companies. A possible suggestion to mitigate the risk of poorly informed managers would be the implementation of a mandatory training program before entering any management role at a construction company. Master Builders also suggested that business training modules should be implemented in the building and construction Certificate IV course.[135] Further elaboration of these options is undertaken in Chapter 5.

So, from the discussion above, it can be seen that a variety of factors contribute to insolvency issues in construction companies. Now that the key issues behind construction industry insolvencies have been identified, focus will be turned to exploring the current legislation and measures in place to battle phoenix activity. Chapter 3 analyses the latest reforms introduced in 2020, highlighting their positive and negative aspects.

This chapter will analyse the statutory reforms introduced in 2020 to assist in combatting illegal phoenix activity in the Australian economy, namely the Combatting Illegal Phoenixing Act and Modernisation and Other Measures Act. The amendments will be explained to demonstrate the lengths to which the Australian government has gone to contain this problem, but arguably has ultimately fallen short for reasons advanced in this paper. The statutory reforms focus largely on the protection of creditors as well as corporate tax compliance. It is the intention of these commendable reforms to have offending directors consider running their business in a proper, ethical manner rather than phoenixing at every option.

The Combatting Illegal Phoenixing Act,[136] was introduced in February 2020 to assist with combatting illegal phoenix activity in Australia. The Act contains four schedules, all aimed at addressing specific issues.[137] One of the prominent features of Schedule 1 of the Act is the new ‘creditor-defeating disposition’ statutory provision. This addition, now contained at s588FDB of the Corporations Act, details the type of transactions which should be classified as creditor-defeating and therefore potentially voidable. Property will be considered improperly disposed of if the consideration received was lower than the market value of the property or the best price which should have been reasonably obtainable and the disposal prevented the property from being available to fulfil creditors’ interests in the company’s winding up.[138] The section also provides that the disposition will be considered improper if the company disposes of property and a third party receives consideration rather than the company.[139] Furthermore, ss 588GAB and 588GAC introduce statutory duties on officers to prevent engaging in creditor-defeating dispositions and barring any person from encouraging a company to make these transactions.[140] The introduction of these provisions will be a great step forward in insolvency proceedings as liquidation aims to create the most beneficial outcome for creditors. With these new provisions, creditors are awarded an extra layer of protection from maliciously minded directors who intend to exploit the corporate vehicle for personal purposes and to defeat creditors.

The Corporations Act has also been amended to allow parties such as ASIC, liquidators, and creditors to recover assets and compensation in certain cases. The introduction of s588FGAA allows ASIC to make an order requiring a person involved in a creditor-defeating disposition to transfer property back to the company or repay the company a fair amount representing the benefits the person has received as a result of the disposition.[141] This section also lays out the elements ASIC must have information regarding before making any order. ASIC must have regard to the conduct of the company and its officers, as well as the person the property was transferred to.[142] Additionally, the circumstances of the transaction must be known, including any relationship between the company and the person.[143] The same section also allows liquidators to request that ASIC make an order to recover assets for the benefit of creditors.[144] However, concerns have been raised that the reforms may confer judicial powers to ASIC and therefore be unconstitutional.[145] While the Law Council of Australia supported the proposal to make recoveries for creditors simpler, it was stated that issues may arise due to the conference of Commonwealth power onto ASIC.[146]

Although not a new law reform, this legislative initiative under section 588M adds extra protection for creditors, stating compensation may be recovered for loss resulting from insolvent trading if it is found that a director has contravened subsections 588G(2) or (3) and the creditor has suffered damage as a result due to the insolvency.[147] The debt must have been at least partially unsecured at the time when the loss occurred and the company must be in the winding up stage.[148] This section applies regardless of whether or not the director has been convicted of an offence or had a civil penalty order made against them.[149] According to subsections 588M(2), (3), and (4), a liquidator may recover the amount of loss or damage from the director on behalf of the company, or a creditor may recover the amount due to themself as long as these proceedings are brought within 6 years of the beginning of winding up.[150] Section 588R partners with Section 588M to allow a creditor to bring proceedings against a company that is being wound up to recover the debt owed to them so long as they receive the written consent of the company’s liquidator.[151] Again, the existence of these provisions is a positive step in insolvency proceedings as the government has recognised that creditors must be awarded extra protection due to the information asymmetry which intrinsically exists in business transactions. Information asymmetry can be defined as the difference of information between two agents.[152] Of course, it would be ideal to eliminate this issue, but this would be near impossible as the internal members of a corporation will always have access to more information than external lenders. Creditors will not always know all relevant information before lending and may unknowingly place themselves in a less than optimal situation. Therefore, for now, the statutory provisions discussed contribute to bridging the gap and protecting creditors.

With regards to director resignation, s203AA now prohibits backdating of director resignation to prevent attempts to escape liability and s203AB disallows resignation of a director if, at the end of the day of resignation, the company would be left with no directors.[153] The final amendment to the Corporations Act is the introduction of s203CA which added that a resolution to remove directors within a proprietary company would be void if the resolution resulted in no directors at the end of the day.[154] It can be seen that, overall, the amendments to the Corporations Act have been made for the benefit of creditors and will serve a positive purpose in reducing the amount of illegal phoenix activity seen in the Australian economy.

The Combatting Illegal Phoenixing Act then moves on to amend the Tax Administration Act 1953. As of 1 April 2020, section 268-10 allows the Commissioner to collect a reasonable estimate with regards to GST liabilities.[155] One of the most beneficial amendments is the addition of s269-30, which introduces the director penalty notice. This section states that, if a company does not meet its GST (including luxury car tax and wine equalisation tax), PAYG, or super liabilities, its directors may be held personally liable to recover these debts.[156] This provision is a step forward in preventing illegal activity as late payment and non-payment of taxes tend to be a large factor in the decision to phoenix a company. With the introduction of these PAYG, super, and GST collection options as a result of the Combatting Illegal Phoenixing Act, directors will not always be awarded limited liability as they were prior to these reforms. This amendment to the Tax Administration Act will ensure directors consider all options before avoiding tax obligations as they may become personally liable for the company’s debts.

Finally, s8AAZLGA(1) allows the Commissioner to withhold refunds if a company has outstanding lodgements.[157] These additional provisions will be immediately beneficial as companies often engage in illegal activity in attempts to exploit the tax system as there have not previously been measures in place to retain funds and therefore tax evasion could be seen as a viable option. With these extra precautions in place, it would be reasonable to expect a decline (to some extent) in illegal phoenixing as certain tax liabilities may no longer be avoided. It is the aim of the Act and these amendments to place greater liability on directors to ensure they are engaging in ethical business practices and to encourage directors to exert deeper thought and effort into trying to genuinely revive their company before resorting to illegal asset transfers and liquidation only to create a similar business from the ashes.

It has been mentioned that the construction and building industry harbours an unusually high level of phoenix activity. Common directors continue to exploit the system over years, incorporating companies for a specific project and, when the project is complete and lots are sold, GST is only partially remitted before the company is abandoned and a new, similar company is set up.[158] Directors will then use the profits (which would not exist if GST had been fully remitted) from these ventures on their next project, usually to abandon this again when it is complete. Through the introduction of these provisions, it is intended that directors will give more thought before liquidating companies simply to continue parallel operations as directors will now be liable for the company’s GST liabilities.

The Combatting Illegal Phoenixing Act has also considered some recommendations put forward by the 2015 Parliamentary Inquiry. Gardner and McCoy report that the Act complements government agencies and initiatives, such as the Phoenix Taskforce, implementation of single touch payroll reporting, and the fair entitlements guarantee (FEG) Recovery Program.[159] The ATO has stated that the Phoenix Taskforce now has 38 member agencies, including ASIC, FWO, and Revenue NSW, representing a large range of legal issues such as workplace rights and entitlements, labour hire licensing and a specific interest in the construction industry.[160] The ATO has flagged illegal phoenix activity to mean non-payment of wages, unfair advantages over competitors, and non-payment of suppliers so focuses its efforts on businesses engaging in these activities.[161] It has also been reported that, in the 2018-19 financial year, the ATO completed over 750 audits, collecting $70 million in cash to contribute to government spending and other essential services.[162] As of 31 March 2020, over $1.33 billion in liabilities had been discovered from illegal phoenix activities, with $580 million being recovered to be returned to the community.[163]

It can certainly be seen that the 2020 statutory reforms are a step in the right direction and the amendments which have been introduced as a result have tightened the restrictions regarding illegal phoenix activity. The Act has indeed created provisions to better protect creditor interests whilst simultaneously increasing the accountability of directors, including resigning directors. However, whilst the Act does provide an added layer of protection against illegal phoenix activity, the undercapitalisation issue still has not been addressed. As mentioned above in the ASIC submission, this is a large factor in the failure of businesses in the construction industry.[164]

Another important introduction is the Treasury Laws Amendment (Modernisation and Other Measures) Act (hereafter referred to as ‘the DIN Act’), which received Royal Assent on 22 June 2020 and introduced the concept of the Director Identification Number (DIN) to the Corporations Act. This number is unique to every director, thus allowing for easier following of an individual’s business activities. Part 9.1A of the Corporations Act details the DIN specifics with three key requirements – that existing directors (appointed prior to 1 November 2021) apply for a DIN by 30 November 2022, new directors appointed between 1 November 2021 and 4 April 2022 must apply for a DIN within 28 days of their appointment, and new directors appointed from 5 April 2022 must apply for a DIN immediately upon appointment.[165] Furthermore, the Act prohibits a person from knowingly applying for more than one DIN, whether it is for fraudulent purposes or not, and will forbid misrepresenting a person’s DIN to government agencies.[166] The DIN registration is a much needed protocol and it is promising that the government has now introduced the system.

Parliament has mentioned that the implementation of the DIN will be beneficial in decreasing the volume of phoenix activity as business failure will now be tracked more closely. It is stated that the DIN will “assist regulators to better detect, deter, and disrupt illegal “phoenixing” activities” and improve the collection of corporate data.[167] It will be more difficult for persons to provide fictitious identities when applying for directorships and thus regulators will be able to trace business failures, as well as common directors between business failures, more efficiently.[168] It is reported that, although ASIC currently collects director details, there is currently no obligation to verify what is provided.[169] As a result of this, ASIC’s registers include untrue information, with directors such as Mickey Mouse and Porky Pig being recorded.[170] Furthermore, it is stated that, although it is indeed illegal to provide false or misleading information, as details are not verified there are no repercussions for these activities.[171] Through the introduction of DIN, ASIC will be able to verify directors’ identities, thus reducing the false information in their registers.

In cases of non-compliance, there are several civil and criminal penalties that may apply to individual directors and corporations which courts may apply. Personal penalties may include imprisonment for up to 12 months, fines of up to $1,050,000, or fines of up to three times the amount of the benefit received from the illegal behaviour.[172] Corporations must also be aware not to engage with any violation of the DIN regime as fines may be imposed.[173] Defences are available for non-compliance. If a director fails to apply for a DIN they will need to prove that the registrar did not process their application for a DIN or that the directorship was placed upon them without their knowledge.[174] If a director applies for more than one DIN, they may avoid liability by proving that the registrar directed reapplication or that the initial application was rejected.[175]

The DIN is tied to Australian Company Numbers (ACNs).[176] It is anticipated that, if the DIN is properly implemented, it would prove to be an asset in preventing corporate insolvency at the hands of certain directors with the intention of phoenixing companies.[177] Ideally, ASIC will receive notification once one DIN has been associated with five failed ACNs over 10 years.[178] This will be beneficial as, when directors now apply for their DIN, it may be backdated to former ACNs, thus revealing previously abandoned companies under the same DIN. Therefore, results may be seen immediately.

The positive aspects of the 2020 reforms must be acknowledged as they mark a significant change to the legal landscape and should have a positive influence in decreasing the amount of illegal phoenixing seen in Australia. These reforms are welcomed and demonstrate that the Australian government is ready to take note of and act on the problems at hand. The introduction of the DIN should prove beneficial over the coming years. This addition should reduce administration costs and increase efficiency in tracking insolvency issues in companies with common directors. With these measures, regulatory agencies will be able to follow directors’ business ventures, especially those which have failed previously to watch over high-risk directors who have a history of engaging in phoenix activity.

Additionally, the Combatting Illegal Phoenixing Act has introduced several much-needed reforms to the Corporations Act and Tax Administration Act which will leave a positive impact on the economy. With the inclusion of creditor-defeating dispositions, directors will need to give greater thought to asset transfers and other illegal activities as ASIC will now have the scope to recover damages incurred as a result of these transactions. The new director penalty regime should also prove to be an asset in requiring companies to comply with their GST, PAYG, and super obligations as directors will otherwise be personally liable to meet these payments. Although these reforms will assist in containing the problem of illegal phoenixing, there is still more to be done as regulatory gaps continue to exist in certain areas. These gaps and potential solutions will be discussed in Chapters 4 and 5.

The passage of the Treasury Law Amendment (Combating Illegal Phoenixing) Act 2020 (Cth),[179] is a welcome initiative but is unlikely to present a complete solution to the problem of illegal phoenixing in the construction industry. Although this new law may have a positive impact on the general reduction of illegal phoenix activity in Australia, it is the contention of this thesis, as advanced in Chapters 5 and 6, that regulatory gaps are still likely to exist to fully address the particular problem addressed in the thesis. As part of that contention, this chapter offers a critique on the current law reform, highlighting both the potential strengths and potential weaknesses of the Treasury Law Amendment (Combating Illegal Phoenixing) Act 2020 (Cth). Thereafter, regulatory gaps are identified and discussed further in Chapters 5 and 6 which offer potential solutions for consideration, aimed at a more comprehensive effort to tackle the high incidence of illegal phoenix activities in the construction industry. Part of the solution, going forward, is the urgent need to address current law enforcement culture which is not sufficiently robust.

The explanatory memorandum to the Treasury Law Amendment (Combating Illegal Phoenixing) Act 2020 details how the four schedules to this Act will operate as well as their ultimate purposes.[180] Schedule 1, which covers creditor defeating dispositions,[181] was introduced to protect creditors and is therefore an important, much welcomed section of legislation. Schedule 2 aims at improving the accountability of resigning directors with a goal to decrease illegal phoenix activity and its impact on “employees, creditors and government revenue”.[182] This is to be done by holding directors personally liable for their actions should they intend to cheat stakeholders. Schedule 3, the “estimates regime”, allows the Commissioner to collect anticipated GST liabilities and hold directors accountable.[183] The Schedule aims to deter the occurrence of illegal phoenixing as directors will continue to be tied to GST obligations in cases of wrongdoing regardless of the winding up of a company.[184] Schedule 4 allows the Commissioner to retain tax refunds in certain cases with a similar intention to Schedule 3. That is, if a company is not entitled to receive a tax refund whilst they have outstanding debts, winding down the company upon reception of tax refunds without considering other tax obligations will not be possible anymore. All of the reforms, identified in these Schedules, are likely to be beneficial in addressing the significant phoenixing issues currently seen in the Australian economy.

Professor Helen Anderson reiterated concerns that the introduction of more legislation may not be the most beneficial course of action in reducing phoenix activity.[185] It was mentioned that “attacking illegal phoenix activity through legislation against creditor defeating dispositions will simply encourage the devious to accrue debts through an assetless company and hold assets in another company”.[186] This is indeed a valid concern and it must be questioned whether any amount of legislation would prevent directors with the sole intention of exploiting the corporate vehicle from committing fraud. Professor Anderson highlights s182(1) of the Corporations Act which prohibits directors, secretaries, officers, or employees from using their position for personal gain or to detriment the company and asks whether the new reforms simply reiterate the same notion.[187] A similar point was explored with regards to s588G. Through these criticisms, it can be seen that it is not necessarily the legislation at fault, but the regulation and enforcement of the legislation, and the Australian government should be utilising resources to ensure offenders are appropriately prosecuted. This view was supported by Chartered Accountants ANZ (CAANZ)[188] as well as the Australian Restructuring Insolvency & Turnaround Association (ARITA), who stated it may have been more beneficial to “strengthen existing anti-phoenixing tools” rather than implement “quasi-duplicate mechanisms”.[189]

The Assistant Treasurer praised the reforms, stating “this bill will give our regulators additional enforcement and regulatory tools to better detect and address illegal phoenix activity and, importantly, to prosecute or penalise directors and others who facilitate this illegal activity, such as unscrupulous pre-insolvency advisers”.[190] However, Mr Steven Jones, MP, did mention that the way forward may not be through additional legislation, affirming points made previously by Helen Anderson.[191] He states “right now it’s easier to start a company than it is to open a bank account” thus reiterating Professor Anderson’s call for checks of identification.[192]

Furthermore, Schedule 2 of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Registries Modernisation and Other Measures) Bill 2019 covers the DIN and the explanatory memorandum holds the key aims of this introduction.[193] It is mentioned that, although there are already initiatives in place to reduce phoenix activity, the DIN intends to provide easier traceability of a director’s activities, thus reducing the time and resources required by regulatory bodies to investigate specific directors’ actions.[194] The comparison of prior law to new law highlights the fact that this provision has not been considered previously and will assist in filling a gap in current legislation.[195] Implementation of the DIN regime will prove to be useful in tracking directors’ movements when required and thus reduce unnecessary costs related to gathering information that will now be readily available to regulatory bodies.

In her critique of the proposed phoenixing reforms, Professor Helen Anderson commended many of the introductions but raised the issue of backdating the appointment of directors, stating that this problem must be addressed.[196] Professor Anderson drew attention to a specific case, where an unwitting man, Mr Christopher Somogyi, had been made a “dummy director” of two companies for a seasoned phoenix operator and tax evader, Mr Philip Whiteman.[197] Professor Anderson stated that it must be accepted by the government that such directors do exist and will attempt to exploit the system in any way they are able.[198] Although, with the introduction of the new provisions, directors are unable to backdate their resignation, the risk of disappearance by the fraudulent director remains, leaving the innocent party open to harassment by authorities.[199] The government must be proactive in protecting the more vulnerable members of society who may fall victim to such schemes and instead focus its efforts on capturing the real offenders. It was mentioned in the submission that the introduction of the DIN (to come into effect in 2021) will hopefully decrease the occurrence of such events.[200]

Following the discussion on the positive and negative features of the 2020 law reform, attention is now turned to identifying the regulatory and other gaps which remain in the legal framework, with a fuller discussion next in Chapter 5.

The discussion in Chapter 5 centres on:

i. The expanded role of Security of Payment (SOP) Acts. The specifics of the current SOP regime will be explored as well as the importance of the implementation of a national SOP Act.[201]

ii. Undercapitalisation, which continues to be an issue in construction companies and the government has not yet introduced any reforms aimed at combatting this issue. Many sources have flagged this issue as a major factor behind the failure in the construction industry.[202] Although this concern has been raised on multiple occasions, minimum capital requirements have not been implemented in legislation or even discussed in government proposals. It is readily conceded that minimum capital provisions will have both positive and negative effects. Nonetheless, is it an idea worthy of exploration for, on balance, the advantages may well outweigh the disadvantages.

iii. Director restriction will also be explored as an alternative to director disqualification and this will be tied to the DIN.[203] Director restriction measures will allow for a distinction of punishment between directors who intend to commit fraud and exploit the system and directors who are simply uneducated or incompetent without malicious intent.[204] This will be an important consideration as it will help educate directors while they continue to manage a limited number of companies whereas pure disqualification would not allow this opportunity.[205]

iv. The beneficial owners’ register, as mentioned in Veda’s recommendation[206] remains unnoticed by the Federal Government. Transparency remains a large issue in the construction industry and stakeholders or regulatory bodies may not necessarily be aware of exactly who is in charge of a business based on the directors listed in ASIC’s database. It will be important to explore this issue as the implementation of such a system would be beneficial in the promotion of honesty in the industry. The beneficial owners’ register would be especially important in instances such as the Somogyi and Whiteman case,[207] as fraudulent directors would have a more difficult experience in shifting blame away from themselves.

v. A call is also made for statutory trusts as a way to protect creditors from poor payment practices. These trusts would add a layer of security for vulnerable parties as head contractors would not be able to use funds at their discretion as monies would be held for the benefit of subcontractors.

vi. As tax avoidance is a common thread among phoenix operators, analysis of the Treasury’s 2017 reform proposal paper entitled “Combatting Illegal Phoenixing” will be conducted.[208] This proposal explores the potential for regulatory bodies to identify certain entities as higher risk, thus pre-emptively flagging potential phoenix operators so they may already be on a watchlist. These special entities may also be required to satisfy additional compliance requirements to prove that they are operating legally.

vii. The need to promote director education in general, and business training in particular for participants in the construction industry which has a high incidence of corporate failure. Education of directors, especially in start-up companies, is a large issue and tends to lead to problems in the management of a business, leading to eventual insolvency in many cases.[209] As mentioned in Chapter 2, the workers in the industry who become managers tend to be trained in the hands-on aspects of the job but have not been taught managerial skills and therefore are unable to operate with the level of business acumen the job may require.[210] Therefore, it will be important to recommend the introduction of mandatory business training courses alongside apprenticeships or, at least, when workers are elected for management positions. Possible alternatives to be considered will be discussed in Chapter 5.

viii. Lastly, but equally important, a call is made for more robust law enforcement by the regulatory agencies, in particular by the corporate regulator ASIC.

These gaps in the armoury to target illegal phoenix activity in the construction industry are explored next, in Chapter 5, to recommend tailored reforms to the problems in this industry where were specifically identified in Chapter 2.

It should be noted that a major force behind the failure of businesses in the construction industry is the hierarchical, pyramid structure, with the failure of larger corporations affecting all companies below them.[211] It is not a secret that businesses in the construction industry face failure as a result of this structure so often seen but the government has not discussed potential avenues to contain the issue, likely due to the unique nature of the industry as projects generally require a certain amount of manpower which may only be achieved through this type of arrangement. The introduction of an obligatory flatter business model may prove to be beneficial as the collapse of a larger corporation could be spread among all subcontractors rather than creating a ripple effect down the chain. However, it must be acknowledged that it would be difficult to mandate such a situation and enforcement may be demanding, and therefore this option is not explored further for this reason.

This chapter has explored the current reforms and measures in place to combat illegal phoenix activity and has identified areas which are still of concern. It is clear that the Federal Government is ready to address phoenix activity seriously and additional steps must be made while focus remains on the problem. Chapter 5 will build on the concerns identified in this Chapter by offering potential solutions to each of the key issues.

This chapter addresses the regulatory and other gaps that exist in tackling the problem of illegal phoenixing generally, and in the construction and building industry in particular. In addition to the existing legal framework, the chapter considers a myriad of other potential solutions (identified at the end of Chapter 4) to help decrease or alleviate the problem.

This chapter explores the specifics of the current SOP regime as well as the important need to implement a national SOP Act as an aid to combat illegal phoenixing. It is widely accepted that the construction industry faces challenges with payment practices, especially regarding subcontractor payment, thus leaving those workers at the bottom of the pyramid structure vulnerable to exploitation. According to NSW Fair Trading, the SOP Acts aim to ensure that employees within the construction industry are paid fairly.[212] As the construction industry mainly relies on contractors, regular employee benefits are not provided, thus opening a large portion of the industry’s workers up to exploitation through non-payment and other avenues. The NSW SOP Act[213] allows for “fair and timely remuneration of construction work” and entitles contractors to ‘progress payments’ for work they have delivered.[214]

The various SOP Acts in the other Australian states require attention and it would be beneficial for the Federal Government to consider implementing a national standard to ensure clarity as differences exist between state models. There is currently a decent amount of disparity between the state-based Acts. The Senate Economics Reference Committee suggested a more national approach as it viewed SOP as a helpful measure to combat illegal phoenix activity in the construction industry.[215] The Federal Government has not yet commented on the possibility of a national SOP Act but this should be discussed as a step forward in national legislation. With late payments and disputes regarding payment being a constant theme in construction businesses, it will be important to fully analyse and appreciate the benefits of a national SOP system which may be enforced with greater ease.

The Department of Employment released a review in February 2017 to tackle the key issues surrounding the Security of Payments Acts including the current effectiveness of the legislation, differences in timeframes, and quality of adjudication.[216] This inquiry was conducted to analyse the current regime and identify steps that may be taken to “overcome the current fragmented nature of security of payments laws” as well as why subcontractors seem to refuse to exercise their rights under the legislation.[217]

Attention is drawn to the risks of continuing to operate Australia’s SOP regime on a piecemeal basis. The features and operations of the SOP will be discussed in this chapter to highlight the differences in the Act which exist between state jurisdictions, thus making it unnecessarily difficult to follow and inevitably resulting in avoidable costs and confusion within the construction industry. If a clearer national approach is considered subcontractors may not be so apprehensive to engage in litigation. As the SOP Acts exclusively affect the construction industry, consolidation of the Acts would demonstrate to workers that the government is ready to understand their needs and fight for their rights rather than supporting a system that grants excessive power to corporations with already sufficient resources.

The two systems for SOP laws are the ‘East Coast’ and ‘West Coast’ Models. Both methods consist of an ‘interim payment regime’ which aims to ensure that subcontractors are paid regularly and receive full compensation.[218] The East Coast Model contains a statutory payment method that will override inconsistent contractual provisions whereas the West Coast Model only provides legislative assistance.[219] Furthermore, the East Coast Model states that, once a payment claim is received by the respondent, they may respond with a payment schedule or, if this is not provided, the respondent will be liable for the entire claim amount.[220] This is not the case in the West Coast Model and “[a] party who does not respond to a payment claim by way of a payment schedule is not liable to pay the claimed amount”.[221] It seems as though the East Coast Model is more beneficial to subcontractors and therefore, due to the power imbalance between the parties, it may be beneficial to implement the East Coast system nationwide.

In Chapter 9 of the 2015 Inquiry’s final report, the problems associated with these SOP Acts were detailed, such as false statutory declarations, cost of enforcement, and speed of adjudication. Mr Dave Noonan, national secretary at the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union, explained that, for contractors to submit applications for payment from those higher up in the chain, they must declare that they have first paid their subcontractors and employees.[222] According to Mr Noonan, “It is notorious that statutory declarations that are false are filed around the industry”.[223] The Committee recommended that ASIC and the ATO continue to develop programs that may “monitor the integrity of the payment system” to avoid the exploitation of the statutory declarations.[224] It was also suggested that state governments take false declarations seriously and possibly prosecute directors who have engaged in such activity in an attempt to deter similar behaviour.[225] In Queensland, the state government published de-identified information regarding the outcomes of disputes to educate the community and the Committee recommended that this be implemented nationwide.[226]