|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal Student Series |

ARTIFICIAL ISLANDS: ARE THEY THE FUTURE?

MEGAN JONES

Land is an important but limited resource, unequally divided and with different properties depending on its location and geophysical makeup. As a result of the power which land can grant those who control it, it is also regulated by a variety of legal mechanisms. This essay will canvass how successful and appropriate these mechanisms are with respect to artificial land, with a focus upon its actual use by individuals as a place to inhabit, rather than the well-traversed ground of the international law issues raised by such islands. Finally, this article will conclude with a warning against treating artificial land as any other land, based on various forms of instability, and promote it being used primarily for green and community space.

I INTRODUCTION

Land is commonly conceptualised as a finite resource, but that has not stopped centuries of artificial land creation – the construction of which has only become more reliable with modern technology.[1] Countries and city-states like Singapore, Dubai, Hong Kong and Macau have been some of the biggest adopters of artificial island creation, with islands like Sentosa and the Palm Jumeirah being tourist destinations in their own right, as well as such land being used for infrastructure projects including Hong Kong Airport.[2] This land is contentious in and of itself; there are international law disputes over expansions of states further into the sea with respect to exclusive water claims, as well as broader issues surrounding sustainable access to desirable land.[3]

However, in a future almost inevitably marked by climate change, rising sea levels and greater demands on desirable space,[4] there is a real question as to how artificial land will respond to these challenges. It is currently posited as somewhat of a solution to these phenomena,[5] but in order to realise that potential, legal, environmental and insurance risks will need to be managed. This essay will examine the degree of instability posed by artificial islands in these three dimensions, and then argue that the most effective and appropriate management of the risks posed by these islands is through limiting its potential use to green and community space.

Figure 1 An image of land reclamation taking place in 2011 as part of the construction of an artificial island and the Gardens By the Bay attraction at Marina Bay in Singapore. Image is the author’s own.

A Definition

As a preliminary matter, it is important to define the bounds of an ‘artificial island’. This concept is contested within the academic literature, and very much depends on the discipline from which the literature emanates. Given that almost all legal discourse with respect to artificial islands focuses upon the international law of the sea and national security, this essay will adopt a modified version of the Hayward and Fleury planning definition.[6] Under this definition, artificial islands will include reference to road-networked artificial islands and finger island canal estates, as well as traditional artificial islands built up by sediment dumping.[7] In essence, if it looks like an island and there has been human-driven land reclamation, it will be treated as an artificial island.

II ARTIFICIAL LAND AS CONTENTIOUS

Land is contentious; it is synonymous with power, money and status.[8] It is also contentious because the place where one lives is at the heart of an individual’s personal life – it is what we live on at all times.[9] These two statements are true with respect to both private and public concerns surrounding land. Artificial land is a mere species of land; it is not immune to the broader issues affecting land more generally. However, this essay argues that there are two particular values which make artificial islands particularly contentious.

A Waterfront Property

Access to shelter in the form of housing is both a human need and a human right,[10] but not all forms of shelter are viewed as equal. In capitalist property markets, particular inclinations towards certain types of housing are expressed through increased property prices, given that land is not an unlimited resource.[11] One such clear tendency is a global desire for housing near water, expressed in a price premium for waterfront real estate.[12]

This tendency has resulted in significant commercial endeavours to increase access to housing near water via artificial islands.[13] Dubai, a desert city-state in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), has used the Palm Jumeirah development to increase its coastline.[14] Singapore, a city-state in South East Asia, has similarly built out sand islands and coastline at both Marina Bay and Sentosa Island to increase the stock of available waterfront property.[15] Even in nations with a generous coastline like Australia, there have been efforts to increase such stock, with Hope Island and the Finger Island Canal Estates on the Gold Coast in Queensland being prime examples.[16]

The very nature of a competitive property market is itself contentious; if shelter is a human right, does that not mean that all individuals should be entitled to it? As raised by Oakley in the Australian context[17] and Brazeau in Canada,[18] it is arguable that waterfront property raises serious and significant equity concerns. Not only is regional and outer suburban waterfront land being gentrified, and in that process stripped away from its lower-income residents, but it is not appropriate for waterfront land to only be accessible to higher-income individuals. Finally, the commercial imperatives and profit potential in waterfront real estate investment mean that backing has been received for unstable or unwise projects, which is also an equity concern where urban property owners are individuals or family units who may have insufficient information to address or truly judge such risks (despite a question lingering over whether the answer to such a question would impact their decisions).[19]

It would be remiss not to also mention that waterfront property is not only desirable for residential living - it is also commercially attractive and has other utilitarian purposes. Hong Kong International Airport sits on an artificial island in order to maximised waterfront exposure, for two safety-focused reasons. Firstly, it assists in the management of pollution, whether noise-based or gaseous, and secondly, it encourages safe aircraft handling practices, which demand access to water and space.

B Artificial Islands and Security

The second value which makes artificial islands contentious is state prioritisation of their own security interests, particularly as a result of public international law rules expressed in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).[20] This makes artificial islands both a potential security risk and asset.

UNCLOS is almost universally recognised as the legitimate basis for international law with respect to the sea, including the multi-level sea boundaries of individual states.[21] As a matter of basic principle, UNCLOS territorial boundaries and waters extend from islands which form part of a state, but there is significant legal contention over how this applies to artificial islands; specifically, whether they ‘count’ as islands from which boundaries are calculated.[22] From a state security perspective, there are clear advantages to a more extended sea boundary, as it provides states with a greater area of exclusive control with respect to economic activities (like fishing) and military incursions.[23] The South China Sea Arbitration between China and the Philippines is a key example of an international dispute over artificial islands and the boundaries which they create around themselves, highlighting the national security concerns raised with militarisation and expansion of far-flung islands for both the building country and its neighbours.[24]

Artificial islands can also raise ownership disputes, such as the Pedra Branca dispute between Singapore and Malaysia in the International Court of Justice.[25] This dispute concerned land which is planned for urbanisation, including habitable dwellings, through the construction of an artificial island around the current small, rocky outcrop.[26] Not only is waterfront land contentious, but in small city-states like Singapore any major land acquisition is particularly significant with respect to managing economic growth and ensuring domestic policy stability – both with state security implications.[27] It was also important in that it changed legal boundaries with respect to vessel movement allowances in the water between Singapore and Malaysia.[28]

Clearly, these islands are contentious and raise multiple concerns which must be diplomatically balanced – but are likely subject to an overriding ‘national’ interest of any party involved, which may also strip legal decisions of meaning (most notably, the South China Sea decision) and make actions unpredictable.

III ARTIFICIAL LAND AND INSTABILITY

The scarcity of waterfront land has not meant that humankind have worked out how to protect it well as an asset, either legally or environmentally.[29] Artificial islands only exacerbate some of these underlying tensions because of their uniquely vulnerable nature, arising from a combination of physical instability and high desirability.[30] The result is that these structures are marked by several different kinds of instability, both legal and environmental. In the absence of legal scholarship on this issue, this essay will build upon the work of Papadakis to identify some of the risks posed by artificial islands beyond international law.[31]

A Legal Instability

Land is generally not thought of as legally unstable in common law jurisdictions, due to clear systems of title management and transfer, at the very least between legal and natural persons.[32] However, the legal structures used to manage artificial islands can make their ownership unstable. This essay will focus on instability in common law systems, comparing Queensland’s Gold Coast with Singapore. Hong Kong and the United Arab Emirates have been excluded from substantive analysis because of additional complexity and uncertainty introduced by unstable political situations. However, the instabilities highlighted below are only heightened by this risk of significant spontaneous government interference.

1 Expropriation

One of the most extreme legal options available in both the Australian and Singaporean jurisdictions is expropriation of land. In neither state is this particularly popular or widespread, arising from a shared capitalist economic system and an understanding that stable freehold housing is part of the political compact with citizens that gives a particular government legitimacy.[33] However, it is notable that Singapore has specific expropriation provisions with respect to reclaimed land that essentially provide no limits on government action, nor a right to a remedy.[34] Whether these provisions are used or not, it does suggest forethought by the Singaporean government as to future management of more vulnerable artificial land – whether it requires the creation of more land in front of the land in question, or abandonment of land if the cost outweighed the benefit of a greater land mass.

2 State Legislative Doctrines

Artificial islands are also regulated by a variety of other legislation. Much of this legislation is not adapted specifically for artificial islands, nor for vulnerable land more generally, and is more concerned with where artificial land is created than its maintenance.[35] As a result, this legislation is locale-specific, but there are also development-specific acts.[36]

The first of these other legislative frameworks are related to ownership of land. Neither Australian nor Singaporean law distinguishes between the different types of land when determining available types of ownership. Whether a piece of land is available for freehold or leasehold title (and the content of that title) is not an assessment based upon the way in which that land was created.[37] In this sense, artificial land is no more volatile or unstable than any other piece of land. However, Queensland and Singaporean law gives the government ownership of all reclaimed land upon the point of reclamation, which can then be transferred to another party – neither piece of legislation mandates transfer to whomever has done the work.[38] This makes artificial islands more unstable than traditional doctrines of land, to the extent that it is likely governments walk back on their agreements. Given both have expropriation doctrines anyway, and are stable governments, this is practically unlikely.

The second set of legislative frameworks focus upon the creation and development of artificial islands. In both Queensland and Singapore permission is required to construct an artificial island.[39] However, the processes for receiving approval are somewhat dissimilar, with Singapore practically having one single expert body making a holistic assessment (the Urban Redevelopment Authority in line with the Singapore Master Plan) with possible later additional ecologically protective tweaks,[40] and Queensland having approval broken up into multiple stages.[41] Relevantly, at no place does Queensland legislation require a consideration of the impact of having an artificial island holistically; instead, bodies like the Gold Coast Waterways Authority consider part of the impact of the development, such as tidal management.[42] Instability is found here only in the Queensland scheme, with multiple levels of approval that do not intermix – leading to disputes where the full consequences of artificial island maintenance have been overlooked and payment is due.[43] Singapore creates instability in a different way though, in explicitly excluding property owners from a right of recourse for damage caused by land reclamation to their property – whether physical or economic.[44]

The third set of legislative frameworks are related to the regulation of existing land and how it is used. States have zoning powers to control land use on artificial islands in the same way as any other piece of land.[45] This is practical, although it should be noted that experience in the US suggests price fluctuations may result, and this itself may be controversial.[46]

3 National Security

The final form of legal instability relevant to artificial land is predicated upon the fraught position of artificial islands in international law under UNCLOS.[47] Although, as surmised in Part II, these can be important security assets, they also leave such land more vulnerable to warfare and intra-state disputes. Given Australia’s large land mass and geographical distance from other nations, this is far more relevant to city-states like Singapore in South East Asia, whose national security situation is more tenuous and fragile.[48] Pedra Branca again provides a clear example of land intended to be used for non-military purposes like residential and commercial development which may be under threat from international legal action attempting to annexe that land.[49]

B Environmental Instability

The second major category of instability faced by artificial islands is geographic. The creation or expansion of islands where they did not previously exist presents several environmental issues, including erosion, waterway and marine environment management, and also exposes that land to rising sea levels.[50] This paper will not attempt to canvass the full environmental instability posed by artificial islands, partly because its extent remains unknown.[51] However, it will make brief comments on the actual stability of artificial islands in a climate change context, the risk of erosion, and ecological fragmentation.

Modern artificial islands are not the most sturdy of constructions. If they are reclaimed islands (almost all artificial islands used in urbanised spaces), they are often constructed by depositing sand or other material, and then reinforcing that structure with concrete or other hard barriers.[52] The instability of these islands has been most clearly evidenced in Penang, where in order to restore stability to an artificial island so that it didn’t ‘wash away’ and continued to provide economically valuable storm protection, mangroves had to be re-planted (or kept) despite commercialisation plans for that particular region.[53] Such interventions are also taking place in Singapore.[54] Not only does this conform with known poor ecological outcomes for built environments, but it suggests that artificial islands may need more substantive ‘nature-focused’ interventions than ‘typical’ land. It also implies that this will become more necessary as climate change increases weather intensity and raises sea levels, increasing flooding risk (as modelled in Singapore).[55]

Artificial islands, as man-made structures attempting to oppose natural land deposition patterns, also rely to a great extent on coastal interventions like sea walls. These interventions, beyond creating physical instability, fragment ecosystems by literally putting up dividing walls.[56] These interventions are also linked with increasing salinity, turbidity and temperature – although the research is more correlative than causative.[57]

This is not to say that artificial islands are entirely negative; they also provide space for the development of artificial reefs, which are often included in construction plans and can be highly productive spaces with disaster prevention effects as well.[58] However, this does not outweigh the environmental destruction these structures otherwise wreck.[59]

C Insurance, Private Relationships and Instability

In capitalist societies, the role of insurance is to provide a social cost-sharing mechanism as part of a response to ‘misfortunes’ which may occur – including environmental disasters.[60] With respect to land, insurance generally operates by requiring a premium to be paid on a regular basis, with payouts available if a protected risk eventuates. With few exceptions, the higher the risk posed to a piece of land, the higher the premium cost.[61] It has also been suggested that the ‘safer’ a piece of land is, the more desirable it is – and therefore more expensive, such that cheaper land could be categorised as more vulnerable.[62] However, this analysis is based on an assumption of rationality on the part of human actors which should not be maintained.[63]

It is clear that waterfront and artificial land is generally more vulnerable land, as a result of geographic pressures like erosion and heightened susceptibility to natural phenomena like storms.[64] However, it is equally clear that waterfront land carries a price premium, such that a majority of landowners are from a higher socio-economic class, as demonstrated in Part II-A.[65] As a result, despite an expectation of such land being less desirable, economic data points to the contrary conclusion – or at the very least, vulnerability resulting in increased premiums not being an effective dampener on land value.

Hence, the relevant question is whether this is a position that results in instability. The answer is yes.

The adoption of risky behaviour which relies on insurance if the worst should eventuate (instead of altering the course of action taken to avoid possible consequences) represents the moral hazard inherent in insurance.[66] Insurance only works where reasonable costs are adequately shared, even if that amount must be topped up by governments.[67] As a result, building to the maximum on vulnerable waterfront land or artificial islands in search of profit, in reliance on insurance to protect otherwise unsustainable buildings, is both inherently and equitably unstable.[68] Whilst land development in both Australia and Singapore is a commercial enterprise, the enormous profit available in waterside property encourages a reliance on insurance to manage physical risks which would not normally be tolerable.[69] This is not to mention insurers likely curtailing their coverage at some point.[70]

Secondly, because insurance is a social cost-sharing mechanism, over-encouraging risky and vulnerable development on reliance on insurance requires the lower and middle socio-economic classes to subsidise the choices of the highest socio-economic classes – the only people with sufficient wealth to access and afford waterfront property.[71] Again, the issue of moral hazard arises, but is now compounded with equity issues surrounding the subsidisation of the wealthiest citizens’ private luxuries.

The other type of private legal relationship relevant to artificial land derives from title. Artificial islands require investment in order to be built, and where capital is supplied it needs to be repaid. The result of this situation is that horizontal strata title is the basis of many artificial land developments.[72] This is significant because strata title empowers the implementation of positive covenants, including those which demand payment – both standard rates and special levies.[73] Insurance does not cover these rates, but they can be excessive, in the tens of thousands in a single notice, raising further justice issues around land affordability.[74] The reason for the existence of such charges and levies is partially that the owner of the strata development is in charge of maintaining public amenities like roads, parks, and any structural or mechanical work needed to keep the artificial island afloat – and do so costs money.[75] As clearly demonstrated with the Hope Island litigation, there is instability inherent in a situation where enormous sums of money can be levied consistently and exceptionally to fund public goods like bridges.[76] There is no guarantee, even if landowners are high SES, that they will be able to afford such rates.

IV RISK MITIGATION FOR ARTIFICIAL LAND

Once it is established that artificial islands are not only contentious for a variety of reasons, but also pose a host of instability risks, it must be asked how these landforms can be managed appropriately and with some sense of equity. This is because it is clear that artificial islands are not going away, particularly for city-states or places with tight spatial limitations.[77] The commercial opportunities and national security benefits they present, as highlighted in Part II, are likely to continue to outweigh their instability. Therefore, this essay suggests that artificial islands ought to be used for ‘green space’ or community space almost exclusively.

A The Importance of Green and Community Space

Both shared spaces and green spaces are necessary for human flourishing.[78] These spaces provide room for the building of social connection, are linked with health improvements, and attract commercial enterprise.[79]

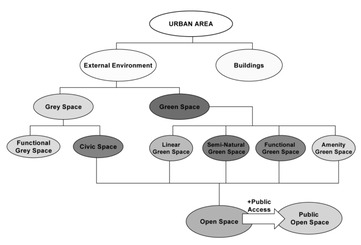

Defining green and community space is an imperfect task, as the public and private spheres of life consistently overlap.[80] However, this essay will adopt an expanded view of the definitional structure used by Swanwick et al in 2003. Swanwick divides the external environment into green and grey space, and then the grey space into functional and civic space.[81] Green and community space refers not only to all of Swanwick’s green space, but also space used for civic purposes – whether in building form or not. It does not include functional grey space, which encompasses roads and other necessary infrastructure. In essence, this definition combines Swanwick’s work with that done by Gaffikin[82] to create a negative definition: any space not used for industrial or residential purposes.

Figure 2 A definitional hierarchy of types of places within cities, classified as urban areas. Swanwick divides non-building areas into a variety of categories, which can be used to describe any other space which is not a building itself. This includes roads, which fall under functional grey space, and picnic parks, which are amenity green space. Taken from Swanwick et al in ‘Nature, Role and Value of Green Space in Towns and Cities: An Overview’ (2003) 29(2) Built Environment (1978-) 94 at page 97.

These spaces are especially valuable in the urban context. Beyond the health and wellbeing consequences linked with adequate space, such as mitigated disease spread and improved mental health,[83] they are crucial in giving all parts of an urban space a ‘shared future’.[84] Most relevantly, these sorts of public spaces can assist in breaking down socio-cultural barriers and re-establishing bonds between different parts of the community.[85] Although this category of place is most effective at this goal when it criss-crosses a city,[86] it provides a neutral space that is often social-justice positive by being more open to all people.[87]

B Land and Personal Life

Secondly, not all land is equally important to members of society. The land on which a person lives is an important part of their personal life and flourishing, and it has a direct impact on their wellbeing.[88] This appears to hold true even when a person does not own that land, or has more tenuous legal ties to it (such as living in a caravan park),[89] and such a link has been indirectly legally recognised through equitable doctrines of specific performance.[90] It was also recognised by Justice Kirby in Wurridjal with respect to compulsory acquisition that justice with respect to land may not be compensable in mere monetary terms.[91]

In contrast, the land upon which a business operates is not nearly as significant. Corporations operate with a much stronger view towards profits,[92] particularly where they are larger companies, and the same sorts of personal ties to land do not arise to the same extent.[93] As a result, where land cannot or ought not be salvaged, mere monetary reparations may be appropriate – and may not be as damaging to the fabric of society and land-based political compact on which many legal systems (Australia and Singapore included) depend.[94]

C A Plan: Weighting Values

There are a multitude of factors which ought to be considered in making a decision about the use of land. Some of these are justice-focused, like the positive social cohesion benefits arising from shared public space[95] and a concept of equitable cost-sharing.[96] Yet others are driven by environmental and legal instabilities. Where artificial islands are going to have a continued existence, this essay argues that green and community space ought to be preferred over residential development.

This model has already been somewhat adopted in Singapore, with the Sentosa and Southern Islands development, all of which are heavily dependant on reclaimed land. 79.3% of their total land is “reserved for open space and recreation”, with approximately 10% for residential development.[97] Sentosa Island has since become a major tourist attraction and entertainment destination for locals; most relevantly, 25% of all visitors to the island were local residents in FY 2018/19.[98] Clearly, a model built around community space is a workable, commercially viable option.[99] This success is echoed by Palm Jumeirah in Dubai, where the strong commercially viable assets remain including Atlantis at the Palm.[100]

Figure 3 Map of Sentosa Island and Attractions. The image is north-facing, with the Singapore Strait at the right of the image. Green spaces are denoted by the colour green, and commercial and community spaces by the colours yellow and purple. In essence, the space to the left of the black line is the 'public' or entertainment-focused part of Sentosa, with the space to right of the black line being the residential part of Sentosa Island. Image taken from Tam Wai Hong Illustration for Changi Travel Services.

However, the Sentosa model has two significant drawbacks. The first is use of the land most exposed to the Singapore Strait for residential purposes, and the second is the legal structure used to run the island. The Sentosa Development Corporation is a public entity that owns and controls the entire island,[101] and whilst this may be accepted in Singapore, the degree of control it exerts is much less likely to be accepted in nations like Australia.

Therefore, from a legal standpoint a similar effect may be able to be achieved using altered zoning maps and planning restrictions specifically targeted towards artificial islands.[102] These would include density and use limitations present from the founding of the development. Unlike the Sentosa model though, a different limit would be set on residential housing: one defined in terms of distance from the closest seaward point, where dwellings would only be able to be built if they were more than 50 - 100m from it. There is no need for a complete ban, but any permission to build on artificial land should be cognisant of risk regardless of the commercial reward.

Furthermore, this type of limit would both allow for property close to water, but also permit the use of non-residential land as an ecological buffer as in Penang. Not only does this give residents and visitors the benefits of green spaces, but as discussed in Part III, buffer vegetation can also provide economic benefit in minimising natural disaster damage and stabilising the island to decrease maintenance costs.[103] It would preserve a recognition of an individual desire to live near water, whilst taking appropriate risk mitigation steps.

However, the most important advantages of both the zoning-plus and Sentosa approaches are that some of the more deleterious effects of the instabilities canvassed in Part III of this essay would be mitigated, whilst allowing access to other benefits from alternative uses of the land. The most important of these is that it would be a better management of the insurance justice and moral hazard issue. Commercial businesses or government are able to contribute to the insurance of the vulnerable land, and are more likely to have the resources to spend additional money correctly to reinforce said land. Hopefully, this would also stop some of the disputes in horizontal strata communities about outsize financial responsibility for certain assets like roads.[104]

A zoning-plus approach also promotes justice; business or arts districts or leisure spaces are more likely to be open to all, so that no-one is legally barred from a public amenity like the waterfront which they are indirectly paying for through taxes or insurance premiums. There is some justice, as well, in removing the risk of residential property damage from those for whom it is so entwined with their inner life, and passing some of that onto commercial entities with fewer feelings. It is further worth noting the environmental justice aspect; the more green space in an urban place, the more environmental mitigation it can be part of, offsetting some of the damage caused by the construction of the island in the first place.

This is not to say, of course, that limited use restrictions of the kind proposed are likely to have any impact on all of the instabilities this essay has canvassed, or access the full benefits of other advantages discussed. In particular, there is unlikely to be any impact on some of the state security concerns vis-a-vis artificial islands mentioned in Part II - B. There is also sound research to support local green space (within 0.5 km) being of the most value in terms of the beneficial impacts of the external environment upon individuals, where those spaces are connected throughout the city.[105] However, where green space is broadened to include civic space, there is also research to suggest that central spaces of particular weight can bear a disproportionate burden in bringing a population together.[106] In Australia, the centrality of the beach in the national psyche is likely to be a sufficient draw to overcome the 0.5km ‘reluctance limit’ – allowing some of the neutral space barrier breakdown seen in green and civic spaces to occur, even if at a lesser rate. Particularly given Sentosa’s broad appeal across the Singaporean population, which suggests it has broken said barrier, this seems like the more likely outcome in an Australian context.[107]

V CONCLUSION

Artificial islands occupy a significant place in our cultural consciousness, whether as mere tourist attractions, status symbols of other nations, or our homes.[108] However, their instability in multiple respects means that their use needs to be carefully considered, despite personal and national desires for waterfront property and security bolstering. Legally, environmentally, and with respect to insurance and personal harm, it is clear that the appropriate use of the land is for green space and community space that can be shared, in order to mitigate risks whilst still extracting benefit. This is still an economically viable solution, modelled off Sentosa Island in Singapore, but also one with real concern for justice.[109]

[1] Ernst Frankel, ‘Prefabricated and Relocatable Artificial Island Technology’ in Frank Davidson, Ernst Frankel and Lawrence Meador (eds) Macro-Engineering (Woodhead Publishing, 1997) 155, 156.

[2] R. Glaser, P. Haberzettl and R.P.D. Walsh, ‘Land reclamation in Singapore, Hong Kong and Macau’ (1991) 24 GeoJournal 365, 365; Kerry Rutz, ‘Artificial Islands versus natural reefs: the environmental cost of development in Dubai’ (2012) 1(2) International Journal of Islamic Architecture 243.

[3] Susan Oakley, ‘Governing Urban Waterfront Renewal: the politics, opportunities and challenges for the inner harbour of Port Adelaide, Australia’ (2009) 40(3) Australian Geographer 297; South China Sea Arbitration (Philippines v China) (Award) (Permanent Court of Arbitration, Case No 2013-19, 12th July 2016).

[4] See e.g. Ministry of National Development, A High Quality Living Environment for All Singaporeans: Land Use Plan to Support Singapore’s Future Population (Concept Plan No 3, January 2013) 4.

[5] Ibid; Michael Gagain, ‘Climate change, sea level rise, and artificial islands: Saving the Maldives’ statehood and maritime claims through the constitution of the oceans’ (2012) 23 Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy 77.

[6] Philip Hayward and Christian Fleury, ‘Absolute Waterfrontage: Road Networked Artificial Islands and Finger Island Canal Estates on Australia’s Gold Coast’ (2016) 2 Urban Island Studies 25, 26 – 29.

[8] See generally Tomas Koontz, ‘Money talks? But to whom? Financial versus nonmonetary motivations in land use decisions’ (2001)14(1) Society & Natural Resources 51.

[9] Janice Newton, ‘Emotional attachment to home and security for permanent residents in caravan parks in Melbourne’ (2008) 44(3) Journal of Sociology 219, 220, 222; Alice Mah, ‘Devastation but also home: Place attachment in areas of industrial decline’ (2009) 6(3) Home Cultures 287, 292.

[10] Universal Declaration of Human Rights, GA Res 217A (III), UN GAOR, UN Doc A/810 (10 December 1948) art 25(1).

[11] Oakley (n 3); Brooke Wildin and John Minnery, ‘Understanding city fringe gentrification: the role of a 'potential investment gap'’ (Conference Paper, State of Australian Cities National Conference, 2 December 2005) 5.

[12] Chris Eves and Alastair Adair, ‘An Analysis of the Sydney Prestige Waterfront Property Market: 1991–2002’ (2005) 11(1) Pacific Rim Property Research Journal 45, 45; David Wyman and Elaine Worzala, ‘Dockin' USA—A Spatial Hedonic Valuation of Waterfront Property’ (2016) 25(1) Journal of Housing Research 65.

[14] See Nakheel, ‘Palm Jumeirah’ (Webpage) <https://www.nakheel.com/nakheel-palm-jumeirah.html>, which manages the Palm.

[15] Ministry of National Development, A High Quality Living Environment for All Singaporeans: Land Use Plan to Support Singapore’s Future Population (Concept Plan No 3, January 2013).

[16] See generally Hayward (n 6) 26 – 29.

[17] Oakley (n 3) 305 – 307, 314.

[18] Evan Brazeau, ‘Making Waves: Ensuring Housing Equity on Toronto’s Urban Waterfront’ (Masters of Urban Planning Thesis, McGill University, 2018) ix – x, 14.

[19] Kostas Koufopoulos, ‘Asymmetric Information, Heterogeneity in Risk Perceptions and Insurance: An Explanation to a Puzzle (Discussion Paper #402, London School of Economics, February 3 2002) 2.

[20] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, opened for signature 10 December 1982, 1833 UNTS 3 (entered into force 16 November 1994) arts 60, 121(1) (‘UNCLOS’).

[21] Imogen Saunders, ‘Artificial Islands and Territory in International Law’ (2019) 52 Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 643, 647 – 652.

[22] Ibid 645 – 652.

[23] Ibid 644 – 645; UNCLOS (n 20) art 48, pt V.

[24] South China Sea Arbitration (Philippines v China) (Award) (Permanent Court of Arbitration, Case No 2013-19, 12th July 2016).

[25] Sovereignty Over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia v Singapore) (Judgment) (International Court of Justice, General List No 130, 23 May 2008).

[26] Ministry of National Development, ‘Development Works at Pedra Branca to Enhance Maritime Safety and Security’ (Press Release, July 5 2021).

[27] On the basis that economic prosperity and domestic stability is essential to a nation’s security planning; Ministry of National Development, A High Quality Living Environment for All Singaporeans: Land Use Plan to Support Singapore’s Future Population (Concept Plan No 3, January 2013) 4.

[28] Sovereignty Over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia v Singapore) (Judgment) (International Court of Justice, General List No 130, 23 May 2008) [28] – [30].

[30] Ibid; Les Watling, ‘Artificial Islands: Information needs and impact criteria’ (1975) 6(9) Marine Pollution Bulletin 139, 139 – 140.

[31] Nikos Papadakis, ‘Artificial Island in International Law’ (1975) 3(1) Maritime Policy and Management 33.

[32] State Lands Act (Singapore cap 314 1996 rev ed) s 14; Property Law Act 1994 (Qld) ss 19 – 20; see generally Land Title Act 1994 (Qld); Donald Nichols, ‘Land and economic growth’ (1970) 60(3) The American Economic Review 332.

[33] Beng-Huat Chua, Political Legitimacy and Housing: Singapore's Stakeholder Society (Routledge, 2002) i - iv; Land and Urban Policies for Poverty Reduction (Proceedings of the 3rd International Urban Research Symposium, April 2005) 284.

[34] Foreshores Act (Singapore cap 113 1985 rev ed) ss 5, 7.

[35] See e.g. Planning Act 2016 (Qld) s 3.

[36] See e.g. Sentosa Development Corporation Act (Singapore cap 291 1988 rev ed); Sanctuary Cove Resort Act 1985 (Qld).

[37] State Lands Act (Singapore cap 314 1996 rev ed) s 14; Property Law Act 1994 (Qld) ss 19 – 20; see generally Land Title Act 1994 (Qld).

[38] Land Act 1994 (Qld) s 127; Planning Act 2016 (Qld) s 19; Foreshores Act (Singapore cap 113 1985 rev ed) s 5.

[39] Land Act 1994 (Qld) s 13; Foreshores Act (Singapore cap 113 1985 rev ed) s 4.

[40] Urban Redevelopment Authority Act (Singapore cap 340 1989 rev ed) pt III; Wildlife Act (Singapore cap 351 2000 rev ed) s 10; Ministry of National Development, A High Quality Living Environment for All Singaporeans: Land Use Plan to Support Singapore’s Future Population (Concept Plan No 3, January 2013).

[41] Integrated Resort Development Act 1987 (Qld) pts 2, 3, ss 5, 26, 35, 52; Planning Act 2016 (Qld) s 19.

[42] Gold Coast Waterways Authority Act 2012 (Qld) ss 10 – 12; Gold Coast Waterways Authority, ‘Development: Reclamation of land under tidal waters (Board Policy, 22 June 2020) 4.

[43] Australand Land and Housing No. 5 (Hope Island) Pty Ltd & Ors v Gold Coast City Council [2006] QSC 332 at [2], [12], [88]-[91]; see also Hope Island Resort Holdings v Bridge Investment Holdings Pty Ltd & Anor [2004] QPEC 003 [37] where knowledge of breach was in issue.

[44] Foreshores Act (Singapore cap 113 1985 rev ed) ss 6, 7.

[45] Planning Act 2017 (Qld) ss 317 – 318.

[46] Jeffrey G. Robert, Velma Zahirovic-Herbert, ‘The influence of privately initiated rezoning on housing prices’ (2021) International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis 10.1108/IJHMA-02-2021-0016 1.

[47] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, opened for signature 10 December 1982, 1833 UNTS 3 (entered into force 16 November 1994) arts 60, 121(1).

[48] Sovereignty Over Pedra Branca/Pulau Batu Puteh, Middle Rocks and South Ledge (Malaysia v Singapore) (Judgment) (International Court of Justice, General List No 130, 23 May 2008).

[49] Ministry of National Development, ‘Development Works at Pedra Branca to Enhance Maritime Safety and Security’ (Press Release, July 5 2021).

[50] Su Yin Chee et al., ‘Land reclamation and artificial islands: Walking the tightrope between development and conservation’ (2017) 12 Global Ecology & Conservation 80, 81, 89.

[51] See generally Watling (n 30) 141.

[54] Ibid.

[55] T. S. Teh et al., ‘Future sea level rise implications on development of Lazarus Island, Singapore Southern Islands’ (2010) 130 WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 121, 129 – 132.

[57] Watling (n 30) 139 – 140.

[58] Chee (n 50) 90; Vieira da Silva et al., ‘Impacts of a Multi-Purpose Artificial Reef on Hydrodynamics, Waves and Long-Term Beach Morphology’ (2020) 95 Journal of Coastal Research 706, 706 – 707.

[60] Tom Baker, ‘Containing the Promise of Insurance: Adverse Selection and Risk Classification’ in Aaron Doyle and Diana Ericson (eds), Risk and Morality (University of Toronto Press, 2nd ed, 2003) 258, 258 – 259; Don MacDonald, James Murdoch and Harry White, ‘Uncertain Hazards, Insurance, and Consumer Choice: Evidence from Housing Markets’ (1987) 63(4) Land Economics 361, 361. See generally Andrew King et al, ‘Insurance: Its Role in Recovery from the 2010 – 2011 Canterbury Earthquake Sequence’ (2014) 30(1) Earthquake Spectra 475.

[62] Ibid 361 – 362, 369 – 370.

[63] Ibid 362 – 364.

[67] Carolyn Kousky et al. The Emerging Private Residential Flood Insurance Marked in the United States (Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes Centre Report, July 2018) 40.

[71] Ibid 262 – 264.

[72] Michael Weir, ‘Strata title, dispute resolution and law reform in Queensland’ (2018) 26(3) Australian Property Law Journal 361.

[73] Land Title Act 1994 (Qld) s 97A(3).

[74] Australand Land and Housing No. 5 (Hope Island) Pty Ltd & Ors v Gold Coast City Council [2006] QSC 332 [44] – [59].

[75] Ibid.

[76] Ibid; Hope Island Resort Holdings v Bridge Investment Holdings Pty Ltd & Anor [2004] QPEC 003.

[77] Ministry of National Development, A High Quality Living Environment for All Singaporeans: Land Use Plan to Support Singapore’s Future Population (Concept Plan No 3, January 2013) 4.

[78] Andrew Lee, Hannah Jordan, Jason Horsley, ‘Value of urban green spaces in promoting healthy living and wellbeing: prospects for planning’ (2015) 27(8) Risk Management Healthcare Policy 131, 132; Carys Swanwick, Nigel Dunnett and Helen Woolley, ‘Nature, Role and Value of Green Space in Towns and Cities: An Overview’ (2003) 29(2) Built Environment (1978-) 94, 102.

[79] Ibid; Amparo Verdú-Vázquez et al, ‘Green space networks as natural infrastructures in PERI-URBAN areas’ (2021) 24 Urban Ecosystems 187, 188.

[80] Frank Gaffikin , Malachy Mceldowney and Ken Sterrett, ‘Creating Shared Public Space in the Contested City: The Role of Urban Design’ (2010) 15(4) Journal of Urban Design 493, 496.

[83] Lee (n 78) 132; see Payam Dadvand and Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, ‘Green space and health’ in Mark Nieuwenhuijsen and Haneen Khreis (eds) Integrating Human Health into Urban and Transport Planning (Springer, 2019) 409.

[85] Ibid 495 – 497.

[86] Ibid 510 – 511.

[87] Swanwick (n 78) 103 – 104.

[88] Newton (n 9) 220, 222; Mah (n 9) 292.

[89] Newton (n 88) 227, 229 – 230.

[90] See Burnitt v Pacific Paradise Resort Pty Ltd [2006] ANZ ConvR 218.

[91] Wurridjal v The Commonwealth of Australia (2009) 237 CLR 309 at [207] (Kirby J).

[92] See Corporations Act 1901 (Cth) s 181.

[94] Chua (n 33); Australian Constitution s 51(xxxi).

[95] Gaffikin (n 80) 495 – 497; Swanwick (n 78) 103 – 104.

[98] Sentosa Development Corporation, Sentosa Annual Report FY 2019/20 (Annual Report, 01 Jan 2020) 6.

[99] Sentosa Development Corporation, Sentosa Annual Financial Report FY 2020/21 (Annual Financial Report, 01 Jan 2021).

[100] Atlantis The Palm, ‘About Atlantis, the Palm’, Atlantis The Palm Homepage (Webpage) < https://www.atlantis.com/dubai/atlantis-the-palm>.

[101] Sentosa Development Corporation Act (Singapore cap 291 1988 rev ed) ss 9 - 10.

[102] Planning Act 2017 (Qld) ss 317 – 318.

[104] Australand Land and Housing No. 5 (Hope Island) Pty Ltd & Ors v Gold Coast City Council [2006] QSC 332 at [2], [12], [88]-[91]; Hope Island Resort Holdings v Bridge Investment Holdings Pty Ltd & Anor [2004] QPEC 003.

[106] Gaffikin (n 80) 510 – 511.

[107] Sentosa Development Corporation, Sentosa Annual Report FY 2019/20 (Annual Report, 01 Jan 2020) 6.

[108] Mark Jackson and Veronica della Dora, ‘ “Dreams so Big Only the Sea Can Hold Them”: Man-Made Islands as Anxious Spaces, Cultural Icons, and Travelling Visions’ (2009) 41(9) Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 2086.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJlStuS/2022/8.html