|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Victoria University Law and Justice Journal |

MODERN FAMILIES: SHOULD CHILDREN BE ABLE TO HAVE MORE THAN TWO PARENTS RECORDED ON THEIR BIRTH CERTIFICATES?

PAULA GERBER[∗] AND PHOEBE IRVING LINDNER[∗∗]

Same-sex couples are becoming parents in increasing numbers through the use of IVF and alternative insemination, and to a lesser degree through surrogacy and adoption. Often, these couples form their families using a sperm or egg donor whom they know, and with whom they have agreed will also be a parent to the child. In these circumstances, children may have more than two people who are their parents. Birth certificates have not kept pace with these changes in family structures. Although every Australian state and territory allows children with two lesbian mothers to have both mothers registered on their birth certificates, there is no provision allowing for more than two parents to be recorded. This article analyses the purpose of birth certificates, and the domestic and international law relating to these important documents. It considers what other countries are doing to ensure that children in same-sex families can have all their parents recorded on their birth certificates, and concludes with recommendations about how Australia should modernise its birth certificates to allow for the recording of up to four parents.

In every Australian state and territory, lesbian couples that have a child together can both be named on their child’s birth certificate.[1] In this way, Australia is a pioneer in recognising the rights of children in same-sex families. However, Australia does not yet adequately protect the rights of children in all diverse family structures, as birth certificates are still limited to recording just two parents.

The concept of a ‘nuclear family’ consisting of a mum, a dad and two children, is quickly becoming a cultural relic, as families formed through artificial reproduction and blended families become more common.[2] Many lesbian couples are choosing to have children using the sperm of a male who is known to them; for example, a gay friend or the brother of the non-birth mother, and who will be actively involved as a father in the child’s life.[3] Families consisting of four parents also now exist, for example when a gay couple and a lesbian couple decide to create a family together.[4] Despite the existence of these new family formations, there is no process, in Australia, for more than two parents to be recorded on a child’s birth certificate. This is an issue that needs to be addressed.

Who is a ‘parent’ is not always easily determined, and ascertaining whether a man is a known donor who is involved in a child’s life, or a parent, can be complicated. Factors that will influence such a determination include, but are not limited to, the extent and nature of the contact with the child, the intention of the parties and the child’s view about who their parents are.[5]

This article briefly examines the purpose of birth certificates, before considering the practical and psychological impacts that a birth certificate can have on children in same-sex families. This analysis highlights the importance of children having birth certificates that accurately reflect their family structure. This is followed by a consideration of the legislation regulating birth certificates, using Victoria as a case study which exposes the limitations on birth registration imposed on families consisting of more than two parents.

Every person has a human right to birth registration and a birth certificate.[6] It is therefore important to consider relevant international human rights norms in order to see what, if any, guidance is provided regarding what information should be recorded on a birth certificate. Human rights norms will be examined in order to determine whether Australia’s current practice of only allowing two parents to be recorded on a birth certificate is consistent with its international human rights law obligations.

The conclusion reached is that legally recognising all parents has a significant and positive practical and psychological impact on a child. In order to comply with international human rights norms and reflect modern society, Australian states and territories should enact legislative reform to ensure that children with three or four parents can obtain birth certificates that accurately reflect their family structure, identity and parentage. British Columbia provides a useful regulatory model for such reform.

A birth certificate is the most visible evidence of respect for every child’s unique identity.[7]

Birth certificates benefit the individual, both practically and psychologically. From a practical perspective, birth certificates provide an individual with a means of establishing their identity.[8] They are a ‘proof of identity document’,[9] which is required in many aspects of a person’s life, such as enrolling in childcare or school, obtaining a passport or driver’s license, and getting a tax file number.[10] Birth certificates provide a child with an ‘all-important proof of their name and their relationship with their parents and the state.’[11]

Birth certificates also have a significant psychological impact on an individual. The way in which a person’s parentage is denoted on their birth certificate can significantly shape that person’s sense of identity. Kertzer and Arel argue that ‘the practice of inscribing cultural categories on personal identification documents can clearly affect an individual’s own sense of identity.’[12] Whilst Kertzer and Arel recognise that ‘literature is lacking on the relationship between state-enshrined identities on personal documents and collective identity formation,’[13] they assert that ‘everyone should be able to establish details of their identity as individual human beings.’[14] As birth certificates are currently restricted to record only two parents, children with three or four parents are denied the opportunity to have their family unit accurately recorded and their identity reflected in these essential documents.

Some argue against legal recognition of tri- and quad-parent[15] families, raising concerns about the welfare of the child in the event of a relationship breakdown, complexities in custody battles and the division of financial responsibility.[16] Bradford Wilcox argues that ‘three parents will have more difficulty giving their children the kind of consistency and stability that they need to thrive as children and as young adults.’[17] Similarly, Diane Wasznicky states that ‘if divorce is difficult for children who have two parents, imagine it with three or four.’[18] However, Samantha Brennan adeptly responds to these concerns noting that, in a world where there are so many children in need of care, ‘there is something odd about people worrying about children having too many people who care for them.’[19]

Birth certificates are one of the ways that the law recognises families. The way in which a child’s family is recorded on their birth certificate sends a message to the child and their family about how they are viewed by the government. Adiva Sifris argues that ‘the Australian family law system remains mired in a two-parent model of legal parentage, a paradigm that does not always reflect the reality and diversity of same-sex families.’[20] Modernising birth certificates to allow up to four parents to be recorded, would demonstrate that the government recognises tri- and quad-parent families as no less real or valuable than families consisting of two parents.

The way in which a child’s family is recorded on his or her birth certificate may also have a sociological impact on their lives. While there is currently little research on the impact of failing to recognise more than two parents on a child’s birth certificate, extensive research has been conducted into sociological issues faced by children of same-sex families.[21] Participants in the Australian Lesbian Parenting project reported that:

being part of a family which is recognised in the law can assist children, along with their parents, to feel more ‘at ease’, ‘respected’, ‘accepted’, and ‘acceptable’, and less likely to feel the need to be ‘vigilant’ and ‘brave’ or be ‘selective’ about who to speak about the family with.[22]

It is reasonable to expect that children in families with more than two parents would similarly feel a greater amount of acceptance from the government and the community if they had a birth certificate that included all their parents.

Legislative reform permitting more than two parents to be recorded on a birth certificate could be the catalyst for positive social change.[23] It has been found that:

Legal reform [sends] a strong message to the community that the family of a child of lesbians is as legitimate and deserving of support and protection as any other. The flow-on effects in social attitudes are as important ... as legal reform itself, particularly in terms of the acceptance (or otherwise) our children and future children will experience in the broader community.[24]

When reflecting on the diversity of family structures that now exist, Professor Brennan observed that ‘it’s time the law recognizes the shape families take.’[25] Birth certificates should reflect a child’s reality, rather than excluding one or more parents because of technical restrictions, namely that no more than two parents can be recorded on a birth certificate. Legal reform, allowing up to four parents on a birth certificate, would facilitate an accurate portrayal of a child’s identity, and have positive psychological and sociological effects for children in tri- or quad- parent families.

Regulation needs to catch up with innovation.[26]

In Australia, birth certificates fall within the jurisdiction of the states and territories.[27] Although the Victorian legislation – Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1996 (Vic) (‘BDM Act’) – has been chosen for in-depth analysis, the equivalent legislation in the other Australian jurisdictions is virtually identical.[28] There is, however, one notable difference. As illustrated in the table below, there are two jurisdictions that have expressly limited the number of parents that may be recorded on a birth certificate to two.

|

State

|

Legislative prohibition on recording more than two parents

|

|

Australian Capital Territory

|

Parentage Act 2004 (ACT) s 14 states that: ‘Despite

anything in this Act or in any other Territory law, a child cannot have more

than 2 parents at any one

time.’

|

|

New South Wales

|

No explicit prohibition on recording more than two parents.

|

|

Northern Territory

|

No explicit prohibition on recording more than two parents.

|

|

Queensland

|

Births, Death & Marriages Registration Act 2003 (Qld) s

10A (1)(c) states that: ‘not more than 2 people in total may be registered

as the child's parents (however described).’

|

|

South Australia

|

No explicit prohibition on recording more than two parents.

|

|

Tasmania

|

No explicit prohibition on recording more than two parents.

|

|

Victoria

|

No explicit prohibition on recording more than two parents.

|

|

Western Australia[29]

|

No explicit prohibition on recording more than two parents.

|

Table 1. Regulatory framework in each Australian state and territory

Although the BDM Act does not explicitly prohibit more than two parents from being registered on a child’s birth certificate, reading the Act as a whole reveals that such a prohibition is implicit. Section 14 states that ‘a person has the birth of a child registered under this Act by lodging a birth registration statement with the Registrar in a form and manner required by the Registrar specifying any prescribed particulars’. The Birth Registration Statement, through which these particulars are specified, only has space for recording two parents: either ‘mother and father’ or ‘mother and parent’ (in the case of same-sex partners).[30] There is no scope for more than two parents to be registered, and therefore no scope for more than two parents to be named on a child’s birth certificate. Because the BDM Act does not explicitly limit parents to only two parents, the BDM Registrar could potentially amend the Birth Registration Statement to include provision for registering more than two parents. This would enable the desired outcome to be achieved without the need for legislative amendment.

However, s 16 of the BDM Act, which relates to registration of parental details, uses the language ‘the other parent’. Applying the textualist approach to statutory interpretation, it follows that, since the definite article ‘the’ is used in combination with the singular ‘parent’, the intention is that there can only be one other parent.[31] Thus, although the BDM Act does not explicitly prohibit the registration of more than two parents, in the way that the ACT and Queensland do, the legislative intent was clearly to allow for only two parents to be recorded on a birth certificate.

There are two other pieces of legislation that are relevant to the birth certificates of children born to same-sex families via assisted reproductive treatment in Victoria, namely the Assisted Reproductive Treatment Act 2008 (Vic) (‘ART Act’) and the Status of Children Act 1974 (Vic) (‘SoC Act’). One purpose of the ART Act is to prevent discrimination on the basis of gender and sexuality and to secure the legal status of children with same-sex parents.[32] The ART Act amended the SoC Act, by creating an irrebuttable presumption that a mother and her female partner are the parents of a child conceived via assisted reproductive treatment, if they were in a relationship at the time of insemination and the non-biological mother consented to the treatment.[33]

Section 13(1)(c) of the SoC Act states that ‘the man who produced the semen used in the procedure is presumed, for all purposes, not to be the father of any child born as a result of the pregnancy, whether or not the man is known to the woman or her female partner’ [emphasis added]. This is relevant to definition of ‘parent’ in s 4 of the BDM Act, in so far as it further defines who can and cannot be considered a ‘parent’. The effect of this provision is that a child born to lesbians following an assisted reproductive treatment procedure that used sperm from a known donor, can only have his/her mothers recorded as parents. The sperm donor cannot be a ‘parent’, even if he is intended to be a father to the child, in addition to the two lesbian mothers.

Justice isn’t about fixing the past; it’s about healing the past’s future.[34]

Case law is emerging that demonstrates a real and present need for legislative reform, to facilitate the recording of more than two parents on a child’s birth certificate, in appropriate circumstances. This section considers two cases where courts were forced to decide which two of three parents should be recorded on their child’s birth certificate.

The New South Wales case of AA v Registrar of Births Deaths and Marriages [35] illustrates how problematic the restriction of recording only two parents can be. In 2001, a lesbian couple (‘AA’ and ‘AC’) had a daughter (‘AB’), following artificial insemination using sperm donated by a known donor (‘BB’). The lesbian couple and sperm donor met following a series of advertisements. AA and AC placed an advertisement in a gay publication, the Sydney Star Observer, which read:

Lesbian couple seeks donor, view to being “uncle” figure to child. No financial obligation. If interested and would like to talk more about details, contact us...[36]

At around the same time, BB placed an advertisement in a different publication, which read:

Sperm Donour (sic) Professional male mid 40’s would like to meet lesbian lady to view of producing a child. Full health details available involvement and financial assistance offered.[37]

These advertisements demonstrated that at the time the three parties connected, they had a shared understanding that BB would be involved in the life of any child born through this process.

When AB’s birth was registered in August 2001, lesbian mothers in New South Wales did not yet have the right to both be named on their children’s birth certificates. Therefore, only AC, the birth mother, was registered on AB’s birth certificate.[38] AC stated that ‘I left the spot for ‘father’ blank... If it had been possible, I would have listed [AA] as [AB’s] other parent.’[39] BB had no legal entitlement to be named as the father because the Status of Children Act 1996 (NSW) provided that:

If a woman (whether married or unmarried) becomes pregnant by means of a fertilisation procedure using any sperm obtained from a man who is not her husband, that man is presumed not to be the father of any child born as a result of the pregnancy.[40]

By 2002, BB’s relationship with AA and AC had soured, and BB applied to the Family Court and obtained contact orders. In 2002, with the consent of AC, BB’s name was placed on AB’s birth certificate. In an affidavit, AC stated that ‘I agreed to [BB’s] request to go on [AB’s] birth certificate because I was advised by our solicitor at the time that it was the best course of action to settle the Family Court proceedings for contact that [BB] had initiated.’[41]

In the following years, BB performed a role as father to AB. He told the court that he had a close and loving relationship with AB all of her life, and so too did BB’s mother and sister. [42] Furthermore, BB contributed tens of thousands of dollars to AB’s upkeep and has performed acts of great generosity to AC. He sees his position as one of father to AB ‘in all relevant ways.’[43]

Essentially, AB had three parents; her two lesbian mothers and her donor father. She lived with AA and AC until 2006, when the relationship between the lesbian mothers broke down.[44] Consent orders were made in 2007, allowing AA and AC to share parental responsibility, and increasing the amount of time the child spent with BB.[45]

In 2008, the legislation in NSW was amended to allow both lesbian mothers to be named on their children’s birth certificates. It had retrospective effect. In response to this new right, AA commenced proceedings to have BB’s name removed from the birth certificate, so that her name could be placed on the birth certificate in its place. For AA to be recorded on the birth certificate, BB’s name had to be removed because, as already noted, only two parents can be named on a birth certificate.

The New South Wales District Court held that:

... under the provisions of the Status of Children Act ... the rebuttable presumptions in BB’s favour that he is a parent, are displaced by the irrebuttable presumption that because AB was conceived through a fertilisation procedure, he is presumed not to be her parent, whereas AA is presumed to be one of her parents.[46]

As a result, the court ordered that BB’s name be removed from the birth certificate, so that AA’s name could be added.

Judge Walmsley SC noted that ‘no doubt a provision for registration of a third parent for a situation such as this one might be a neat answer to the problem this case presents.’[47] However, he added without elaboration, that ‘there might be unexpected consequences’ which arise as a result of allowing more than two parents on a birth certificate.[48]

The Queensland case of A v C[49] involved an application by a lesbian couple to have a known sperm donor’s name removed from the birth certificates of their two children. A and B were a lesbian couple who wished to become parents together. Their preferred pathway to parenthood was to undertake artificial insemination at home, using a known sperm donor.[50] They found C through a gay community website and contacted him about donating sperm. In her affidavit, A stated that C said ‘I’m happy to put my DNA into the world but I do not really want to be a parent.’[51] C’s evidence contradicted this. He claimed that he told A that he desired a relationship with the child.[52]

A was artificially inseminated with C’s sperm by her partner B and as a result became pregnant with their first child, D, who was born in 2004. At that time, B could not be named on the child’s birth certificate as a parent.[53] A was advised by Centrelink that it would affect her social security benefits if she did not record a father’s name on D’s birth certificate. Therefore, A asked C to sign the birth certificate application as D’s ‘father’.[54]

In 2006, A gave birth to another child, E, who was also conceived using C’s donated sperm. C’s name was recorded as E’s father on the birth certificate. When the children were infants, C had some contact with both D and E. However, by 2010, C had ceased to have contact with the children. In 2013, C sought to resume contact with the children and commenced proceedings seeking orders to allow his involvement in the children’s long-term care, welfare and development. A and B responded by making an application to remove C’s name from the children’s birth certificates.

Judge Ann Lyons ordered that the sperm donor’s name be removed from the two children’s birth certificates, and that the name of the birth mother’s female de facto partner be recorded in its place. Her Honour made this order so as to ‘accurately reflect the correct parents for the children and the true nature of the relationship between A and B.’[55]

Judge Lyons found that A and B were in a de facto relationship at the time of both fertilisation procedures, and C was a sperm donor. Therefore, there was an irrebuttable presumption that B is the parent of the children, to the exclusion of C.[56] Judge Lyons observed that:

A Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages is ... a register of statistical and evidential information mainly for the purposes of succession law. It is not a register of genetic material.[57]

She found that it was essential that the birth certificates properly reflected the children’s families. The extent to which C actually contributed to the children’s lives was not examined extensively in this case. If it were accepted by the Court that the parties had intended the children to have more than two parents, that is, that C have a meaningful role as a father to the children, it would have been appropriate for the Court to have the option of adding C as a parent, alongside the names of A and B.[58] However, as only two parents could be legally named on a birth certificate, this was not possible.[59]

These cases illustrate the need for reform to allow more than two parents to be recorded on a birth certificate in appropriate circumstances, so as to ensure that birth certificates constitute ‘an accurate reflection of the family situation.’[60]

Human rights directs my path.[61]

There are several international human rights norms that are relevant to the issue of what should be recorded on the birth certificates of children in same-sex families. This section analyses:

a. right to birth registration and a birth certificate;

b. best interests of the child;

c. right to identity; and

d. States’ obligations to protect and assist families.

An examination of these rights provides insight into whether international human rights law requires that Australia record all parents on a child’s birth certificate.[62]

Article 24(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights[63] (‘ICCPR’) and art 7(1) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child[64] (‘CRC’) provide that every child shall be registered immediately after birth and shall have a name. In General Comment 19, the Human Rights Committee (‘HR Committee’) found that art 24(1) of the ICCPR ‘specifically addresses the protection of the rights of the child, as such or as a member of a family.’[65] Thus, there is a link between a child’s right to registration and an accurate record of their family. In order for a person’s right to registration to be fully realised, birth certificates should accurately reflect the family with whom that person identifies himself or herself.

Article 7(1) of the CRC states that all children have ‘the right to know and be cared for by his or her parents’, thus establishing an explicit link between identity and parentage. The content of this provision echoes that of art 24 of the ICCPR, and similarly provides little guidance as to the precise content of the right.[66] While the term ‘parent’ is not defined in the CRC, Sifris argues that nothing in the wording of art 7 suggests that it is limited to heterosexual parents.[67] Likewise, there is nothing in the wording that indicates that ‘parents’ should be limited to two parents. At the time the CRC was drafted,[68] tri- and quad-parent families would not have been contemplated. However, human rights treaties are ‘living instruments’[69] and should be interpreted in light of modern society, not frozen in time. As these family structures now exist in Australian society, art 24 of the ICCPR and art 7 of the CRC should be interpreted in such a way that the term ‘parents’ includes all people performing that role.

Article 3(1) of the CRC requires that the ‘best interests of the child’ are a primary consideration in all actions pertaining to children. This article applies broadly and is not constrained to the rights protected within the CRC. This is significant as there are a number of references to ‘both’ parents within the CRC (see arts 9.1, 9.3 and 18.1), which could be seen as limiting the scope of the treaty’s application to two parents. However, as noted above, human rights treaties are ‘living instruments’[70] and should be interpreted in light of modern society. As tri- and quad-parent families are now a reality within Australia and elsewhere, the CRC’s application should be extended to protect children in such families.

Whilst the CRC does not define ‘best interests of the child’, its meaning was considered by the High Court of Australia in Marion’s Case[71] to be ‘imprecise, but no more so than the “welfare of the child” and many other concepts with which the courts must grapple.’[72] Failing to recognise a child’s family on their birth certificate may have a negative practical and psychological impact on the child.[73] Therefore, in order to comply with art 3 of the CRC, and to ensure respect for the rights of children in families with more than two parents, governments should pursue law reform that allows up to four parents to be recorded on birth certificates.

Article 16 of the ICCPR provides that ‘everyone shall have the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.’ Nowak suggests that an individual’s right to birth registration is ‘closely related to the right to his or her identity, which follows from the protection of privacy and the right to recognition before the law guaranteed by article 16.’[74] In order for this right to identity to be fully realised in Australia, birth certificates should provide a mechanism for recording all of a child’s parents on their birth certificate.

Article 8 of the CRC reveals a link between identity and parentage. It requires State Parties to ‘respect the right of the child to preserve his or her identity, including ... family relations as recognized by law.’ The phrase ‘family relations as recognized by law’ is not defined in the CRC and has not yet been elaborated upon by the Committee on the Rights of the Child (‘the CRC Committee’). This phrase should be interpreted in accordance with the ‘best interests of the child’ principle and therefore arguably should be interpreted broadly to have the widest application. In the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission’s report, Same-Sex: Same Entitlements, the Commission found that ‘the definition of “parents” has been interpreted broadly to include, genetic parents, birth parents and psychological parents’, in regards to a child’s right to know his or her parents (art 7) and preserve his or her identity.[75]

Article 23(1) of the ICCPR describes State Parties’ obligations to legally protect the family, stating that ‘the family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.’ The HR Committee has recognised that ‘the concept of the family may differ in some respects from State to State, and even from region to region within a State, and that it is therefore not possible to give the concept a standard definition.’[76] Thus, State Parties have a wide scope for interpreting the term ‘family’ when applying the ICCPR.[77] As tri- or quad-parent families exist in modern Australian society, these should be recognised by the state through the mechanism of birth certificates.

Article 10(1) of the International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights[78] (ICESCR) requires State Parties to provide ‘the widest possible protection and assistance’ to the family, which is ‘the natural and fundamental group unit of society’ and art 10(3) states that ‘special measures of protection and assistance’ are to be taken by State Parties ‘on behalf of all children and young persons without any discrimination for reasons of parentage.’ In General Comment No 4, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (‘CESCR’) found that ‘the concept of “family” must be understood in a wide sense.’[79] In order to provide the widest possible protection for children with tri- or quad-parents, all Australian states and territories should modify birth certificates so that they can accurately represent a child’s family. Such legislative reform would help remove any legal discrimination based on parentage, in accordance with art 10(3).

He who rejects change is the architect of decay.

The only human institution which rejects progress is the cemetery.[80]

In reforming the law governing birth certificates so as to provide for more than two parents, Australia does not have to reinvent the wheel. In the United States of America, nine jurisdictions allow three-parent families to be legally recognised: Alaska, California, District of Columbia, Delaware, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Washington.[81] Some of these states have achieved this recognition through the legislature; others through the courts and adoption proceedings.[82] In Canada, the state of British Columbia has legislated to allow more than two parents to be recorded on a child’s birth certificate. California, Ontario and British Columbia provide three useful models that Australian jurisdictions can look to when considering reform in this field.

In 2012, Senator Mark Leno introduced a Bill to recognise more than two parents on birth certificates.[83] The Bill was designed to provide judges with discretion to recognise parent–child relationships between a child and more than two parents on a child’s birth certificate, when it was in the child’s best interests.[84] The impetus for the Bill was the case of In Re MC,[85] in which the judge had no option but to place a girl in foster care when her legally married parents – two lesbians – could no longer take care of her.[86] Senator Leno recognised that ‘the court did not have the authority to appoint the girl’s biological father, with whom she had a relationship, as a legal parent. That third parent could have benefitted the well-being of the child.’[87] In response, Senator Leno introduced a Bill, which ‘would provide that a child may have a parent and child relationship with more than 2 parents.’[88]

California Governor Jerry Brown refused to sign the Bill into law, stating that he required more time to consider any ‘unintended consequences’ of the Bill.[89] Governor Brown gave no indication of what these consequences might be. However, opponents of the Bill argued that it would have extensive ramifications in regards to tax deductions, probate, social security, wrongful death and education benefits.[90] Furthermore, opponents argued that the Bill would require new guidelines to be put in place to determine child support, which would cost an estimated $6.4 million, according to the Senate Appropriations Committee.[91] The best interests of the child should be the primary consideration when undertaking law reform.[92] The cost to the State of implementing law reform should not take precedent over the welfare of the child.

On 4 October 2013, one year after vetoing Bill 274, Governor Brown finally signed the Multiple Parents Bill into law.[93] When contacted by the media, Governor Brown’s representatives declined to answer questions about why he changed his mind about the bill.[94] The law will authorise courts to ‘recognize more than two parents if endorsing fewer would be “detrimental” to the child.’[95] Whilst the law allows a child to have more than two legal parents, it does not ‘change any of the requirements for establishing a claim to parentage under [California’s] Uniform Parentage Act.’[96] The new law only removes the two-parent limitation.

The strength of the Bill is that it focuses on the best interests of the child. Ed Howard commented that ‘everyone who places the interests of children first and realizes that judges shouldn't be forced to rule in ways that hurt children should cheer this bill becoming law.’[97] However, the law requires families to apply to the courts in order to have more than two persons recognised as a child’s parents. Such a process can be emotionally stressful and financially burdensome, and should not be necessary, unless there is a dispute about who are the child’s parents. The California approach is therefore not recommended as an example of best practice that Australia should follow.

In 2007, the case of AA v BB[98] came before the Ontario Court of Appeals. It involved a lesbian co-parent seeking a declaration of parentage, based on the Court’s parens patriae jurisdiction. The Court found that the child had three parents: his lesbian mothers AA and CC, and his biological father, BB.[99]

The parens patriae jurisdiction could be applied as a legislative gap was identified, which led to discrimination against the child.[100] This gap arose due to the historical drafting of the Children’s Law Reform Act. The Act’s original purpose when drafted, in 1900 was to protect children born outside marriage.[101] Rosenberg JA recognised that, at that time, families of the type seen in this case would not have been considered.[102] The judge exercised the parens patriae jurisdiction to declare that AA is a mother of DD.[103]

However, despite the judge’s recognition of the factual reality of the child having three parents, they could not all be recorded on the child’s birth certificate due to numerical limitations at that time. This case was significant, in identifying the need for reform to enable all of a child’s parents to be legally recognised and protected.

In response, in part, to the Ontario Court’s identification of this gap in that state’s legislation, British Colombia modified s 30 of the Family Law Act[104] to provide an exception to the two-parent limit. This exception applies in cases of artificial insemination, where the birth mother, her partner and the donor all agree, prior to conception, to become parents together.[105] The Vital Statistics Act[106] was also amended to reflect the child’s ability to have more than two parents.[107] The Ministry of Justice of British Columbia commented that ‘establishing rules regarding the circumstances under which there may be more than two parents ensures a consistent approach and provides greater certainty for children and families when planning for children where assisted reproduction is required.’[108] More than two parents can be recorded if:

a. there is a written agreement;

b. before the child is conceived through assisted reproduction; and

c. between the intended parents and the birth mother.[109]

The result of this reform is that up to four parents can now be named on a child’s birth certificate, without having to apply for a court order.[110]

In October 2013, Della Wolf Kangro Wiley Richards became the first child issued with a birth certificate recording three parents (a lesbian couple and their male friend, who is the child’s biological father).[111] Whilst the legislative reform had already taken place, when the three parents went to register the child’s birth online, only two spaces were provided to list the child’s parents.[112] The lesbian mothers therefore requested a paper form and modified it themselves in order to record the biological father, as well as themselves, as parents.[113] As a result, Della was issued with a birth certificate naming all three of her parents.

The secret of change is to focus all of your energy, not on fighting the old, but on building the new.[114]

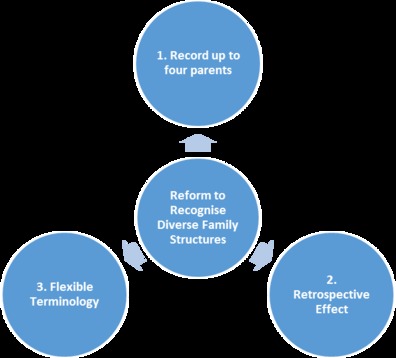

It is vital for the welfare of children that their birth certificates accurately reflect their family reality. Reform to enable this must address three essential elements as set out in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Essential elements of reform of laws governing birth certificates

1. Up to four parents

As noted above, in order to accurately reflect a child’s family, it may be necessary, in some cases, to record more than two parents on a birth certificate. Daniela Cutas suggests that, in determining who is a ‘parent’, the nature of the commitment and relationship between the parents should be awarded less weight than the nature of their commitment to, and relationship with, the children.[115] By focusing on the parents’ relationship with the child, rather than each other, the best interests of the child becomes the primary consideration in regards to who is considered a ‘parent’ for the purposes of the birth certificate.

One way of establishing who is a parent and therefore should be recorded on a child’s birth certificate is to require the intended parents to enter into a written agreement, documenting their intention to co-parent, prior to conception. That intention and family structure would then be reflected in the birth certificate issued following the registration of the birth of the child. This is the approach adopted in British Columbia.[116]

There should be an upper limit of four parents recorded on a birth certificate, in order to avoid any potential (though slight) risk of abuse from cults or sects, posing as large ‘families’. The cases discussed within this article have involved families consisting of three parents: a lesbian couple and a known sperm donor. This is the most common scenario to date, in which more than two parents form a family. However, quad-parent families also exist, in which a lesbian couple and a gay couple come together to have a child.[117] Thus, the BDM Registrar should be able to record up to four parents on a child’s birth certificate.

2. Retrospective

As already noted, the CRC imposes an obligation on Australia to ensure that the best interests of the child are a primary consideration when reforming laws that will impact children. In order to uphold this obligation, legislative reform should explicitly provide that it operates retrospectively. The effect of this would be that children, or their parents, could apply to the Registrar to amend their birth certificate to include additional parents. A retrospective application of a new regime would be consistent with the approach taken when the non-birth mother in a same-sex couple became entitled to be recorded on their child’s birth certificate.[118] The decision of whether or not to allow more than two parents to be registered retrospectively should be made by the BDM Registrar, based on evidence provided by the parties, such as statutory declarations setting out the family structure and the consent of all parties to the birth certificate being amended. There should be no need to go to court for any orders in relation to amending a birth certificate to add additional parents, unless there is a dispute as to who is a parent.

3. Terminology

Recording more than two parents on a birth certificate necessarily raises the question of what is the appropriate terminology to describe parents on the child’s birth certificate. Currently, birth certificates of children born to lesbian parents record one ‘mother’ (the birth mother) and one ‘parent’ (the partner of the birth mother). However, the terminology denoting parentage will require adjustment following the High Court decision in NSW Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages v Norrie.[119] That case held that the Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages must record Norrie’s sex as ‘non-specific’ on the birth registry.[120] This decision may have far-reaching implications on Australian legislation in general, and birth certificates in particular. If a person is registered as of ‘non-specific’ gender on their birth certificate, that person cannot logically fall into the category of ‘mother’ or ‘father’, which are essentially gendered terms. Using the non-gendered term ‘parent’ on birth certificates would avoid discriminating against people of ‘non-specific’ gender. In order for the Norrie case to be applied consistently, birth certificates should allow all parents to be described by the gender neutral term ‘parent’, rather than the gendered terms ‘mother’ and ‘father’.

An example of best practice in regards to terminology on birth certificates can be found in California, where the legislation allows the parents themselves to choose how they are described on the birth certificate of their child – either as a ‘mother’, a ‘father’ or a ‘parent’.[121] This practice avoids any issues that may arise as a result of the Norrie case in regards to respecting gender non-specificity, and allows parents the greatest amount of flexibility to have their identity accurately recorded on their child’s birth certificate.

Together let us build a better future for every child – secure in the knowledge that in serving the best interests of children, we serve the best interests of all humanity.[122]

It is an unfortunate reality that the law often fails to keep up with societal and technological advances. Children are being raised in a plurality of family structures, and it is time that the law recognised the families of these children, by allowing up to four parents to be recorded on a child’s birth certificate.

Birth certificates provide individuals with an official record of their identity. Accurately recording a child’s parents is likely to have a positive impact on a child’s psychological and sociological wellbeing, by providing evidence of acceptance of their family by the government and society. This official recognition will make life easier for children with more than two parents, by making their families more socially acceptable and helping children to feel secure. For these reasons, legislating to allow for accurate birth certificates is in the best interests of the child, and thus consistent with international human rights norms.

The Australian jurisprudence demonstrates an immediate need for legislative reform, to allow all parents of a child to be recorded on their birth certificate. This conclusion is further supported by the jurisprudence of California and British Columbia, where similar issues have arisen due to the limitation of recording only two parents on a birth certificate.

British Columbia represents the preferred model for legislative reform, because it allows for the recording of up to four parents on a birth certificate by the Registrar. This is an improvement on the Californian approach, which requires parents to apply to the court for an order recognising all parents.

The British Columbian requirement of a written agreement between the intended parents prior to conception ensures that there is evidence of the parties’ intention to co-parent before the child is born. This requirement should be mirrored in Australia, as it provides a clear method of determining who is and is not a parent at the time of the child’s birth.

It is essential that legislative reform apply retrospectively, so that tri- and quad-parent families that already exist are also able to benefit from this overdue reform.

Accurately reflecting a child’s family structure and identity should be the primary considerations when recording parents on birth certificates. As Professor Polikoff said:

This is about looking at the reality of children’s lives, which are heterogeneous, as opposed to maintaining a fiction of homogeneity. Families are different from one another. If the law will not acknowledge that, then it’s not responding to the needs of children who do not fit into the one-size-fits-all box.[123]

It is well and truly time to remove the limitation of recording only two parents on birth certificates. Up to four parents should be able to be recorded, if that is necessary to accurately record a child’s family structure. Such reform would be consistent with international human rights law and reflect modern society.

[∗] Professor Paula Gerber, Monash University Law Faculty and Deputy Director of the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law.

[∗∗] Ms Phoebe Irving Lindner, Research Assistant, Monash University Law Faculty.

[1] The changes came into effect in Western Australia in 2002, the Australian Capital Territory in 2004, and the Northern Territory in 2004. See Artificial Conception Act 1985 (WA) s 6A; Status of Children Act 1978 (NT) s 5DA; Parentage Act 2004 (ACT) s 8(1). Next to follow this model of legislative reform was NSW. The change permitting the registration of two mothers was introduced to the Status of Children Act 1996 (NSW) by the Miscellaneous Acts Amendment (Same Sex Relationships) Act 2008 (NSW). Similar legislation came into effect in Tasmania, Victoria and Queensland in 2010. South Australia was the final state to enact legislation allowing both lesbian mothers to appear on their children’s birth certificate via the Family Relationships (Parentage) Amendment Act 2010 (SA).

[2] For a discussion of modern family structures, see: Family Law Council, Report on Parentage and the Family Law Act (2013)1-4; ABC Radio National ‘How Many Parents Can a Child Have?’, Life Matters, 1 November 2011, (Samantha Brennan) <http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/lifematters/how-many-parents-can-a-child-have/3612172> .

[3] See for example, Kay Dibben ‘Judge Orders Sperm Donor’s Name Be Removed as ‘Father’ of Lesbian Couple’s Two Children in State First’, Courier Mail (online), 29 May 2014, <http://www.couriermail.com.au/news/queensland/judge-orders-sperm-donors-name-be-removed-as-father-of-lesbian-couples-two-children-in-state-first/story-fnihsrf2-1226936116691?nk=434458a32f2d6820872684d1cf63bca1> and John Bingham ‘Three Parents as Good as Two for Boy with Lesbian Mothers and Gay Father, Court Rules’ The Telegraph (online), 15 March 2012 <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/mother-tongue/9143717/Three-parents-as-good-as-two-for-boy-with-lesbian-mothers-and-gay-father-court-rules.html> .

[4] See for example, Ian Lovett, ‘Measure Opens Door to Three Parents, or Four’, The New York Times(online), 13 July 2012 <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/14/us/a-california-bill-would-legalize-third-and-fourth-parent-adoptions.html?_r=0> Dutch Debates Three or More Gay Parents per Child, 6 February 2013 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T4Vmzgnx9MY>.

[5] For a comprehensive discussion of the issues around this area see Family by Design, Sperm Donor Legalities: Using (or Becoming) a Known Donor vs an Anonymous Donor (2012) <http://www.familybydesign.com/content/learn/legal/known-sperm-donor/> Rainbow Families Council, Prospective Sperm Donors: Your Legal Status <http://www.rainbowfamilies.org.au/for-prospective-families/prospective-sperm-donors/your-legal-status/> Family Law Council, above n 2; Hedy Cleaver, Ira Unell and Jane Aldgate, Children’s Needs - Parenting Capacity (TSO, 2nd ed, 2011); Andrew Bainham et al (eds), Children and their Families (Hart Publishing, 2003); Allison James,, ‘Parents: A Children’s Perspective’ in Andrew Bainham, Shelley Day Sclater and Martin Richards (eds), What is a Parent?: A Socio-Legal Analysis (Hart Publishing, 1999) 181; Julie Wallbank, Shazia Choudhry and Jonathan Herring (eds), Rights, Gender and Family Law (Routledge, 2010); Jan Pryorand Bryan Rodgers, Children in Changing Families: Life after Parental Separation (Blackwell, 2001)128; Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Findings: Children’s Perspectives on Families <www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/ spr798.pdf>; State Library of New South Wales, Information about the Law in NSW: ‘Legal Status of Parenthood (3 May 2013) <http://www.legalanswers.sl.nsw.gov.au/guides/hot_topics/families/fundamentals/parenthood.html> Eva Steiner, ‘The Tensions Between Legal, Biological and Social Conceptions of Parenthood in English Law: Report to the XVIIth International Congress of Comparative Law’ (2006) 10(3) Electronic Journal of Comparative Law 1 <http://www.ejcl.org/103/art103-14.pdf> .

[6] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, opened for signature16 December1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976) art 24(2); Convention on the Rights of the Child, opened for signature 20 November 1987, 1577 UNTS 3 (entered into force 2 September 1990) art 7(1).

[7] Liz Brooker and Martin Woodhead (eds), Developing Positive Identities: Early Childhood in Focus; Diversity and Young Children ( Open University, 2008) 2.

[8] There is a distinct difference between the role of birth registration and the role of birth certificates, see Paula Gerber and Phoebe Irving Lindner ‘Birth Certificates for Children with Same-sex Parents: A Reflection of Biology or Something More?’ (2015) 18(2) New York University Journal of Legislation and Public Policy 225.

[9] Births, Deaths and Marriages Victoria, Register a Birth (10 July 2014) <http://www.bdm.vic.gov.au/home/births/register+a+birth/> .

[10] Paula Gerber ‘Making Indigenous Australians “Disappear”: Problems Arising from our Birth Registration Systems’ (2009) 34(3) Alternative Law Journal 158.

[11] Brooker and Woodhead, above n 7, 2.

[12] David I Kertzer and Dominique Arel (eds), Census and Identity: The Politics of Race, Ethnicity and Language in National Censuses, (Cambridge University Press, 2002) 5.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Gaskin v UK [1989] ECHR 13; (1989) 12 EHRR 36, 39 quoted in Jill Marshall, Personal Freedom through Human Rights Law?: Autonomy, Identity and Integrity under the European Convention on Human Rights (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2009), 123.

[15] The term ‘triparenting’ was developed by Daniela Cutas in her article ‘On Triparenting: Is Having Three Committed Parents Better than Having Only Two?’ (2011) 37 Journal of Medical Ethics 735.

[16] See Lovett, above n 4; National Public Radio, ‘Three (Parents) Can Be a Crowd, But for Some it’s a Family’, All Things Considered 30 March 2014(Gabrielle Emanual) <http://www.npr.org/2014/03/30/296851662/three-parents-can-be-a-crowd-but-for-some-its-a-family> .

[17] Emanuel, above n 16.

[18] Lovett, above n 4.

[19] Brennan, above n 2.

[20] Adiva Sifris, ‘Gay and Lesbian Parenting: The Legislative Response’ in Alan Hayes and Daryl Higgins (eds) Families, Policy and the Law: Selected Essays on Contemporary Issues for Australia (Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2014)ch 10. .

[21] See, eg, Gary Gates, Family Formation and Raising Children Among Same-sex Couples (January 2012) Williams Institute <http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/census-lgbt-demographics-studies/family-formation-and-raising-children-among-same-sex-couples/> Liz Short, ‘”It Makes the World of Difference”: Benefits for Children of Lesbian Parents of Having their Parents Legally Recognised as their Parents’ (2007) 3(1) Gay and Lesbian Issues and Psychology Review 5; Simon R Crouch, et al, Parent-Reported Measures of Child Health and Wellbeing in Same-Sex Parent Families: a Cross-sectional Survey (BMC Public Health, 2014) 9-10; N Gartrell and H M W Bos, ‘US National Longitudinal Lesbian Family Study: Psychological Adjustment of 17-year-old Adolescents’, (2010) 126(1) Pediatrics 28; L Van Gelderen et al, ‘Quality of Life of Adolescents Raised from Birth by Lesbian Mothers’ (2012) 33(1) Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 1.

[22] Short, above n 22, 12.

[23] Adiva Sifris, ‘The Legal Recognition of Lesbian-led Families: Justifications for Change’ (2009) 21(2) Child and Family Law Quarterly 197, 198.

[24] Short, above n 22, 11.

[25] Brennan, above n 2.

[26] James Quinn, ‘Paulson to Tighten US Mortgage Regulation as Crisis Deepens’, The Telegraph (online), 13 March 2008, <www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/banksandfinance/2785996/Paulson-to-tighten-US-mortgage-regulation-as-crisis-deepens.html>.

[27] Birth certificates do not fall under s 51 of the Commonwealth Constitution , which vests legislative power in the Federal Government. Therefore, the regulation of birth certificates falls within the jurisdiction of state governments.

[28] See Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1997 (ACT); Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1995 (NSW); Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act (NT); Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 2003 (Qld); Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1996 (SA); Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1999 (Tas); Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1996 (Vic); Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 1998 (WA).

[30] It is difficult to obtain a birth registration statement as the BDM Registrar only releases them to persons who have recently had a child. This is in order to prevent the fraudulent registration of births. However, a sample birth registration statement is annexed to the Victorian Law Reform Commission, Birth Registration and Birth Certificates, Report (2013).

[31] Antonin Scalia, A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law (Princeton University Press, 1997) 35–6.

[32] Artificial Reproductive Treatment Act (2008) s 1.

[33] Status of Children Act 1974 (Vic) s 14, inserted by the Artificial Reproductive Treatment Act 2008(Vic) s 147.

[34] Jackson Burnett, The Past Never Ends (29 July 2012) Deadly Niche Press <www.goodreads.com/author/show/6452394.Jackson Burnett>.

[35] [2011] NSWDC 100 (2 August 2011).

[36] Ibid [3].

[37] Ibid [4].

[38] Ibid [8].

[39] Ibid.

[40] The version of s 14 of the Status of Children Act 1996 (NSW) in force at the time of conception.

[41] AA v Registrar of Births Deaths and Marriages [2011] NSWDC 100 (2 August 2011) [10].

[42] Ibid [2].

[43] Ibid .

[44] Ibid [12].

[45] Ibid [13].

[46] Ibid [36].

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid. One can only speculate as to what the Judge had in mind when he referred to ‘unexpected consequences’. Some common arguments against the legal recognition of tri- or quad-parent families include concerns about the welfare of the child in the event of a relationship breakdown, complexities in custody battles and the division of financial responsibility. For discussion of these arguments see: Lovett, above n 4 and Emanuel, above n 16.

[49] A v C [2014] QSC 111 (9 May 2014).

[50] Ibid [14].

[51] Ibid.

[52] Ibid [15].

[53] Section 19C of the Status of Children Act 1978 (Qld), as amended by s 107 of the Surrogacy Act 2010 (Qld), creates a presumption of parental status, as a result, allowing two lesbian mothers to be named on their child’s birth certificate. Prior to this there was no entitlement for two persons of the same sex to be named as parents on a child’s birth certificate.

[54] [2014] QSC 111 (9 May 2014) [18].

[55] Ibid [49].

[56] Ibid [39]. This irrebuttable presumption arises as a result of s 19C of the Status of Children Act 1978 (Qld), as amended by s 107 of the Surrogacy Act 2010 (Qld).

[57] Ibid [48]. This conclusion was based on the historical analysis conducted by Judge Walmsley SC in AA v Registrar of Births Deaths and Marriages [2011] NSWDC 100 (2 August 2011) [35]. He cited The Laws of Australia, volume 20.10 at [8], as the source for this proposition. For further discussion of the purpose of birth registration and birth certificates, see Paula Gerber, Andy Gargett and Melissa Castan, ‘Does the Right to Birth Registration Include a Right to a Birth Certificate?’ (2011) 29(4) Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 434, 442.

[58] Under the British Columbia model, in order for more than two parents to be recorded on a child’s birth certificate, there must be a written agreement between the parties, prior to conception of the child, that they intend the donor to be a parent. See s 30 Family Law Act BC 2011. This model is discussed further in s 6 below, where it is asserted that this constitutes best practice and should be adopted by Australian jurisdictions.

[59] Births, Deaths and Marriages Registration Act 2003 (Qld)s 10A(1)(c).

[60] A v C [2014] QSC 111 (9 May 2014) [42].

[61] Minnie Estelle Miller (2011) Quotes (2011) GoodReads <http://www.goodreads.com/quotes/369316-human-rights-directs-my-path-minnie-estelle-miller> .

[62] For a comprehensive analysis of the international human rights law applicable to birth certificates of children in same-sex families see Gerber and Lindner, above n 8.

[63] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, opened for signature 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976).

[64] Convention on the Rights of a Child, opened for signature 20 November 1987, 1577 UNTS 3 (entered into force 2 September 1990).

[65] Human Rights Committee, General Comment No 19: Art 23 (The Protection of the Family, the Right to Marriage and Equality of the Spouses), adopted at the 39th sess, UN Doc HRI/GEN/1/Rev.9 (27 July 1990) [1].

[66] Gerber and Lindner above n 8.

[67] Sifris, above n 20, 208.

[68] A UN open-ended working group was created in 1979 and drafted the CRC over a 10-year period. It was adopted by the General Assembly in 1989.

[69] The HR Committee has emphasised that the ICCPR should be regarded as a living instrument, with the rights to be ‘applied in context and in the light of present–day conditions’. Human Rights Committee, Views: Communication No 829/1998, 78th sess, HR Committee/C/78/D/829/1998 (5 August 5 2002) (Roger Judge v Canada) [10.3].

[70] Ibid.

[71] Secretary, Department of Health and Community Services v B [1992] HCA 15; (1992) 175 CLR 218.

[72] Ibid 259.

[73] For discussion of the negative impacts of inaccurate birth certificates, see Gerber and Lindren, above n 8.

[74] Manfred Nowak, UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: HR Committee Commentary (N P Engel Publisher, 2nd ed, 2005) 559-60.

[75] Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (Cth), Same-Sex: Same Entitlements: National Inquiry intoDiscrimination Against People in Same-Sex Relationships: Financial and Work Related Entitlements and Benefits (2007) 50.

[76] Human Rights Committee, General Comment No 19: Art 23 (The Protection of the Family, the Right to Marriage and Equality of the Spouses), adopted at the Thirty-ninth 39th sess, UN Doc HRI/GEN/1/Rev.9 (27 July 1990) [2].

[77] Ibid ‘States parties should report on how the concept and scope of the family is construed or defined in their own society and legal system.’

[78] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, opened for signature 16 December 1966, 993 UNTS 3 (entered into force 3 January 1976).

[79] Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, General Comment No 4: The Right to Adequate Housing (Art 11(1) of the Covenant), E/1992/23 (13 December 1991) [6]. This General Comment discusses the right of every individual to adequate housing, however its discussion of the concept of ‘family’ is relevant to the debate discussed in this paper. At [6] the Committee found that: ‘While the reference to “himself and his family” reflects assumptions as to gender roles and economic activity patterns commonly accepted in 1966 when the Covenant was adopted, the phrase cannot be read today as implying any limitations upon the applicability of the right to individuals or to female-headed households or other such groups. Thus, the concept of “family” must be understood in a wide sense.’

[80] Harold Wilson, Speech delivered at the Consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe, Strasbourg, France, 23 January 1967.

[81] Emanuel, above n 16.

[82] Ibid.

[83] California Legislative Information, SB 1476 Family Law: Parentage (24 February 2012) <http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201120120SB1476> .

[84] National Center for Lesbian Rights, ‘Bill Clarifies a Judge’s Ability to Protect Best Interests of a Child who Has Relationships with More Than Two Parents’(Media Release, 24 February 2012) <http://www.nclrights.org/press-room/press-release/bill-clarifies-a-judges-ability-to-protect-best-interests-of-a-child-who-has-relationships-with-more-than-two-parents/> .

[85] 195 Cal App 4th 197 (2011).

[86] Susan Donaldson James, ‘My Three Daddies: California Eyes Multiple Parenting Law’ (3 July 2012) ABC News <http://abcnews.go.com/Health/GMAHealth/california-considers-bill-multiple-legal-parents/story?id=16705628> .

[87] Ibid.

[88] California Legislative Information, above n 83..

[89] In the ‘Governor’s Veto Message’, Governor Brown wrote ‘I am sympathetic to the author's interest in protecting children. But I am troubled by the fact that some family law specialists believe the bill's ambiguities may have unintended consequences. I would like to take more time to consider all of the implications of this change.’ California Legislative Information, SB 1476 Family Law: Parentage<https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billStatusClient.xhtml?bill_id=201120120SB1476>.

[90] Karen Gushta, Gov Brown Says Judges Can’t Give a Child More than Two Parents – For Now (1 December 2012)Impact <http://www.truthimpact.me/index.php/2012/12/senate-bill-1476-jerry-brown/#.VOU8iinNboA> .

[91] Ibid.

[92] Convention on the Rights of a Child, opened for signature 20 November 1987, 1577 UNTS 3 (entered into force 2 September 1990) art 3.

[93] California Legislative Information, SB 274 Family Law: Parentage: Child Custody and Support <http://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201320140SB274> .

[94] Patrick McGreevy and Melanie Mason, ‘Brown Signs Bill to Allow Children More Than Two Legal Parents’, Los Angeles Times (online), 4 October 2013 <http://articles.latimes.com/2013/oct/04/local/la-me-brown-bills-parents-20131005> .

[95] Lori Carangelo, The Adoption and Donor Conception Factbook: The Only Comprehensive Source of US and Gobal Data on the Invisible Families of Adoption, Foster Care and Donor Conception (Access Press, 2014) 128.

[96] Jeremy Byellin, ‘More than Two Legal Parents? A New California Law Makes it Possible’ on Thomson Reuter, Legal Solutions Blog (15 October 2013) <http://blog.legalsolutions.thomsonreuters.com/top-legal-news/two-legal-parents-new-california-law-makes-possible/> .

[97] McGreevy and Mason, above n 94.

[99] AA v BB [2007] ONCA 2 (2 January 2007) [1]. Referred to in AA v Registrar of Births Deaths and Marriages a [2011] NSWDC 100 (2 August 2011) [36].

[100] AA v BB [2007] ONCA 2 [7].

[101] Ibid [20].

[102] Ibid [21].

[103] Ibid [41].

[104] Family Law Act SBC 2011, c 479.

[105] Family Law Act SBC 2011, s 30. The Family Law Act came fully into force on 18 March 2013.

[106] Vital Statistics Act RSBC 1996, c 479. This act is the equivalent of the Births, Deaths and Marriages Act1996 (Vic) it governs the content of birth certificates.

[107] Vital Statistics Act RSBC 1996, c 479, s 3(1) :

Within 30 days after the birth of a child in British Columbia, a statement in the form and containing the information the registrar general requires respecting the birth must be completed and delivered to the registrar general as follows:

(a) by the mother and the father of the child;

(b) by the child’s mother, if the father is incapable, deceased or unacknowledged by or unknown to the mother;

(c) by the child’s father, if the mother is incapable or deceased;

(d) if neither parent is capable or living, or if the mother is incapable or deceased and the father is unacknowledged by or unknown to her, by the person standing in the place of the parents of the child.

(1.1) Despite subsection (1), if a child is born as a result of assisted reproduction, the statement referred to in that subsection must be completed and delivered to the registrar general within 30 days after the birth of the child in British Columbia as follows:

(a) by the parents of the child;

(b) if a parent is incapable or deceased, by

(i) the other parent of the child, or

(ii) if the child has more than one other parent, the child’s other parents.

[108] Ministry of Justice (British Columbia), Family Law Section Notes (2013) <http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/law-crime-and-justice/about-bc-justice-system/legislation-policy/fla/part3.pdf> .

[109] Family Law Act SBC 2011, s 30 Parentage if other arrangement:

(1) This section applies if there is a written agreement that

(a) is made before a child is conceived through assisted reproduction,

(b) is made between

(i) an intended parent or the intended parents and a potential birth mother who agrees to be a parent together with the intended parent or intended parents, or

(ii) the potential birth mother, a person who is married to or in a marriage-like relationship with the potential birth mother, and a donor who agrees to be a parent together with the potential birth mother and a person married to or in a marriage-like relationship with the potential birth mother, and

(c) provides that

(i) the potential birth mother will be the birth mother of a child conceived through assisted reproduction, and

(ii) on the child’s birth, the parties to the agreement will be the parents of the child.

(2) On the birth of a child born as a result of assisted reproduction in the circumstances described in subsection (1), the child’s parents are the parties to the agreement.

(3) If an agreement described in subsection (1) is made but, before a child is conceived, a party withdraws from the agreement or dies, the agreement is deemed to be revoked.

[110] Family Law Act SBC 2011, s 25.

[111] Kimberly Ruble, ‘British Columbia Baby Has Three Different Parents on Her Birth Certificate’, Liberty Voice (online), 11 February 2014 <http://guardianlv.com/2014/02/british-columbia-baby-has-three-different-parents-on-her-birth-certificate/> .

[112] Ibid.

[113] Ibid.

[114] Dan Millman, Way of the Peaceful Warrior: A Book that Changes Lives, (H J Kramer, 1984) 113.

[115] Cutas, above n 15.

[116] Family Law Act SBC 2011, s 30

[117] For an example of a four parent family (a lesbian couple and a gay couple) co-parenting two children see: ‘Dutch Debates Three or More Gay Parents per Child’ (6 February 2013) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T4Vmzgnx9MY>.

[118] Section 13 of the Status of Children Act 1974 (Vic) and s 60H of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth).

[120] For a further discussion of this case see: Paul Bibby and Dan Harrison, ‘Neither Man nor Woman: Norrie Wins Gender Appeal’, The Age (online), 2 April 2014 <http://m.theage.com.au/nsw/neither-man-nor-woman-norrie-wins-gender-appeal-20140402-35xgt.html> .

[121] AB 1951 Vital Records: Birth Certificates (Cal 2014) was introduced by Assembly Majority Whip Jimmy Gomez on 19 February 2014. The Bill provides that, by 1 January 2016, Californian birth certificates will be modified to provide three checkboxes with the options of ‘mother’, ‘father’, and ‘parent’, to describe the identity of the parents.

[122] Carol Bellamy, Speech delivered to the Third World Summit on Media for Children, Thessaloniki, 22 March 2001 <http://www.unicef.org/media/media_10731.html> .

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/VicULawJJl/2015/5.html