University of New South Wales Law Journal

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of New South Wales Law Journal |

|

JOHN H FARRAR[*]

This article traces the development of corporate governance in Greater China and its implications for global corporate governance. Greater China’s case is unique and complex, and differs from the emerging global corporate governance model. The purpose of this article is to investigate why this is so, what the main differences are, whether there is a possibility for some convergence, and what effects this may have on Greater China and the global model.

By Greater China we refer to the People’s Republic of China (‘PRC’), Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macao and (in a very loose sense and mainly by way of comparison) the diaspora Chinese business communities that dominate the economies of South-East Asia.

The three main regions of Greater China — the PRC, Taiwan and Hong Kong — have different recent histories, legal cultures, as well as vastly different economies. The PRC has a system of socialist legality moving closer to a rule of law. Taiwan has had an authoritarian regime but has recently moved towards a more democratic system. Formerly a British colony, Hong Kong is now a Special Administrative Region of the PRC with a limited form of democracy. The PRC has a system of public ownership undergoing corporatisation with only limited private ownership. In Taiwan and Hong Kong family-owned but listed companies dominate the stock exchanges while Hong Kong also serves as an international financial centre. Together these countries represent one of the fastest growing regions of the world.[1]

Corporate governance is concerned with corporate power and accountability. As perceived by the Anglo-American model, it consists of a system of legal rules supplemented first by systems of self-regulation (such as listing rules, statements of accounting practice, institutional codes of self-regulation and codes of individual companies) and secondly by business ethics.[2] This conception of governance accords with the situation in Hong Kong, but not necessarily Taiwan and the PRC. Both systems are in a stage of transition to something closer to this model, due to the pressure following the Asian financial crisis.[3] According to a recent survey,[4] Hong Kong ranked second, Taiwan fifth and the PRC eighth, in terms of the quality of corporate governance in the region. Singapore ranked first.

This article outlines the development of corporate governance in Greater China. Starting with the historic hostility to the corporate form in the PRC, it traces the different paths taken by China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macao, briefly comparing these with the Chinese business networks of South-East Asia. It discusses the extent of this divergence and the possibility of some convergence. In the context of increased globalisation of corporate governance, it is suggested that consideration of Greater China may lead to a greater recognition of different systems of capitalism and corporate governance and a return to an understanding of the role of political economy.

The term ‘corporate governance’ has been in general use for about twenty years although it was used, probably for the first time, in 1962 by Richard Eells of Columbia Business School.[5] It had been thought of in largely domestic terms until around 1999 when, with the growth of international institutional investment, the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (‘OECD’) adopted its Principles of Corporate Governance.[6] These principles have provided a coherent benchmark for the development of what might be called global corporate governance.[7] This is substantially based on a system characterised by private ownership and separation of ownership and control.

Corporate governance cannot be seen in exclusively legal terms. It transcends law and makes increasing use of a variety of forms of self-regulation, the observance of which is substantially determined by the culture of a particular country.[8] For this reason comparative corporate governance cannot be seen simply as a branch of comparative law: it must be considered in broader social scientific terms.[9] However, just as one must resist a tendency to see it in exclusively legal terms, it is also necessary to resist the smothering embrace of the ‘law and economics’ school and see the matter as capable of interpretation in purely economic terms. The development of global capitalism pushes us further in that direction but at considerable political cost. There is a need to rediscover the concept of political economy which was familiar to 19th century writers such as Jeremy Bentham,[10] David Ricardo[11] and John Stuart Mill.[12]

The case of Greater China is particularly interesting from this point of view and raises fundamental questions about the subject of comparative corporate governance and its methodology. Whereas Hong Kong represents an international financial centre built on the twin foundations of Anglo-American law and finance and successful Chinese family business,[13] the PRC until recently rejected this model and favoured a system of public ownership, unclear property rights and lack of an effective regulatory framework.[14] Even Taiwan historically favoured a system with considerable public ownership and control.[15] Macao’s system is based on a Portuguese model.[16] The diaspora Chinese have accommodated themselves to whatever domestic system they encountered, be it the Anglo-American model or the civilian model.[17] The defining characteristic for this group has been the continuing prevalence of the family-controlled enterprise in the private sector.[18] In this respect it has some common characteristics with Taiwan, and as we shall see later, a similar phenomenon is beginning to appear in the private sector in the PRC. At the same time, this is potentially a conservative and reactionary force which may impede further reform.

Thus, concentration on the economy alone is an option simply not available to the PRC government. Indeed, in the case of Greater China as a whole, neglect of political economy will be unfortunate. It is very significant that a study of the role of law in Asian economic development in 1960–95, with input from research teams from different Asian countries, emphasised law and socioeconomic change, and the multi-causal relationship between economic policies, legal systems and economic development.[19]

It is apparent from the outset that the case of Greater China is complex and does not easily fit the emerging global corporate governance model. The task then is to investigate why this is so, what the main differences are, what possibility there is for some convergence and what this may entail for China and the global model. We begin by examining the comparative development of corporate law and governance in the main regions of Greater China.

A The PRC[20]

The history of corporate governance in Greater China begins on the mainland. The corporate form came late to China. It has been said that it came by three routes: the privatisation of central government enterprise, sometimes built upon the family firm, and in a few cases as a result of coordinated regional development.[22]

A distinction is drawn between hang — a combination of merchants — and gongsi, a word invented in Taiwan to describe the Dutch East India Company during the Dutch occupation of what was then Formosa.[23] Later gongsi became a generalised reference to companies with shares. There was resistance to the recognition of this new form in China.[24] Indeed there was little regulation of private economic activity and no commercial code in Qing China.

Eventually the Company Law of 1904 (gongsilu) was adopted.[25] It consisted of 131 articles and recognised four types of gongsi — partnership, limited partnerships and joint stock companies of limited and unlimited liability. The law was not a success; few companies were registered and of these many failed.

The 1904 law was replaced in 1914 by the Ordinance Concerning Commercial Associations (Gongsi Tiaoli). This was a more detailed law based on German law. Chinese capitalists, however, remained suspicious of government and even more suspicious of the public, resisting the corporate form.

The nationalist regime produced many legal codes and a new Company Law in 1929. This revealed traces of German and Japanese influences, but at the same time, this legislation aimed at restricting private capital. State enterprise was favoured in the period 1929–45, accounting for 70 per cent of all paid up capital of public and private enterprise by 1943. In addition, there was resistance to foreign enterprise.

When the Communists took over they found in place a system of state enterprise using the corporate form. They proceeded to demolish the whole legal system and replace it with a more radical communist system.[26]

The communist government resisted the modern corporation until relatively recently. The former system was characterised by extensive public ownership and a rule by law and administrative decree rather than rule of law. However, law is achieving greater prominence and faltering steps are being taken towards a rule of law.

It is increasingly realised — both within and outside China — that the state-owned enterprise (‘SOE’) sector is the Achilles heel of China’s otherwise remarkable economic performance over the past two decades.[28] Enterprise reform occurring in 1978–85 was concerned primarily with the redistribution of enterprise incomes and expanding operational autonomy in favour of management. During 1984–85 there were experiments at local level with shareholding enterprises, but these were simply SOEs raising loans from their employees. Since then there has been some corporatisation of SOEs and conversion of SOEs into joint stock companies, a massive growth in joint ventures with foreign companies and the development of a rudimentary stock market.[29]

In 2000, there were approximately 65 000 state-owned enterprises with at least 51 per cent state ownership and annual sales above five million yuan. These accounted for almost a third of national production, over two thirds of assets, two thirds of urban employment and almost three quarters of investment.[30] Although there has been much liberalisation, SOEs still dominate key parts of the industrial economy, services and infrastructure.

Private enterprises have gradually been recognised as a necessary, beneficial addition to a socialist economy.[31] These include restructured former SOEs and collectives, mixed ownership companies, individual businesses, privately-owned enterprises, private joint ventures with foreigners, and wholly foreign-owned private enterprises. Together, these represented 40 per cent of the national output in 1999.[32] A survey carried out by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences showed that 92.7 per cent of owners of private enterprises in the PRC were also general managers.[33] This also reflects something of the pattern of family ownership and control in Taiwan, Hong Kong and the diaspora Chinese communities.

In March 1999 there were constitutional changes to mark the greater emphasis on the private sector. Article 11 of the Constitution was amended by replacing the words ‘the private economy is a supplement to public ownership’ with ‘the non-public sector comprising self-employed and private businesses is an important component of the socialist market economy’.[34]

The present Company Law 1993[35] came into effect in 1994 and is influenced by Anglo-American and European models to some extent. Under art 2 of the Company Law 1993, there is a division of companies into limited companies and joint stock companies. Article 64 also refers to wholly state-owned companies. These are limited companies established solely by the State Authorised Investment Institution or a department authorised by the state. They are intended for special products or trades.

The Company Law 1993 has a number of distinctive features:[36]

(2) Otherwise, unlike in modern Western systems, the shareholders’ meeting is the organ of primary authority and has wide powers (arts 102–3).

(3) The powers of the shareholders’ meeting and the board of directors are set out in the legislation (arts 103, 112).

(4) The principle of ‘one share, one vote’ applies (art 130).

(5) A shares, B shares, H shares and N shares are all regarded as the same class of shares. The distinctions between them are to do with exchange control restrictions on foreigners (art 130).

(6) There are gaps on many practical matters and no system of minority shareholder remedies in the legislation. Article 111 enables an injured shareholder to seek an injunction in certain circumstances[37] and the code governing civil procedure[38] allows class actions for securities law violations. However, in practice these mechanisms are not used.

(7) The duties of directors are spelt out very briefly (art 123).

(8) China has adopted the German model of a supervisory board for joint stock companies. This does not seem particularly effective due to the difficulty of finding suitable members (arts 124–7).

The main problem in China’s developing corporate governance has been the adoption of basic Western forms without many of the fundamental structures of the Western system. Despite the rapid development of law and steps towards the rule of law, there is no clear concept of private property rights. Most ownership still rests in the state in its various forms.[40] Under the new Securities Law 1998,[41] there are new fledged stock markets with restricted stock, but there is no real market for corporate control.[42]

Western-style management practices are difficult to implement in the confused environment in which state-owned enterprises still operate. The same people are often board members and senior executives and there are conflicts of interest which prevent the separation of business from government. The result is inefficiency, some misappropriation and a lack of accountability. State-owned enterprises are still the major employers and this, combined with inefficiency and hitherto easy access to bank credit, has produced the unfortunate result of many being technically insolvent.

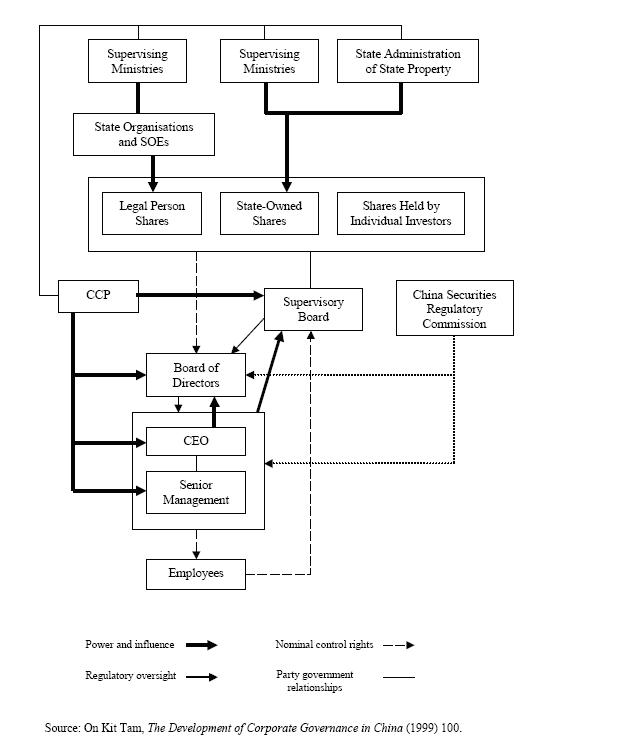

The institutional barriers operating against the effectiveness of the reforms must also be considered. There have been attempts to reorganise the organisational structures of the state asset management system. Currently, there are moves to introduce corporate governance incentives through diversified ownership structures, banking reforms, hard budget constraints with the risk of bankruptcy and attempts to improve accounting and auditing systems.[43] Nevertheless the overall scheme of corporate governance remains complex and somewhat ineffective mainly due to the fact that decisions are made by bureaucracy who lack appropriate incentives. This is shown diagrammatically in Figure 1 on the following page.

The World Bank, in a series of reports and discussion papers over the last 10 years,[44] has made a number of recommendations along Western ‘law and economics’ lines. These have been considered by the Chinese authorities but not necessarily implemented.

More recently, significant changes have been instituted by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (‘CSRC’). These include guidelines on independent directors, introduced on 16 August 2001,[45] and the Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies of 7 January 2002.[46] The former requires listed companies to have at least two independent directors on the board by June 2002, and that independent directors represent no less than one third of board membership by June 2003. This is an ambitious goal. The latter is influenced by the OECD Principles of Corporate Governance and covers shareholders’ meetings, controlling shareholders, boards of directors, supervisory committees, performance and incentive schemes, related party transactions and disclosure. It also recommends independent directors and board committees.

FIGURE 1

The main problems arising from these are the overlap of the independent director system with the existing supervisory board, and other institutional barriers. These will operate against the feasibility of such reforms and include

strong shareholdings often held by emissaries of the state, and the absence of a pool of qualified candidates.

Taiwan, as part of China, was the location of early trading activity by the Dutch East India Company. In 1895, it was occupied by the Japanese as a colony until 1946. Thereafter it was occupied by the nationalist forces after their defeat on the mainland and they took their company law with them into a society which contained some elements of Japanese corporate culture. Because of this complex history, Taiwan’s company law has followed the civil law tradition. Until recently, it has been somewhat archaic, not necessarily reflective of commercial practice, and the influence of law and corporate governance has not been strong. Compared with Hong Kong it does not have a strong infrastructure of experienced courts and public service.[48] Similar to the PRC, Anglo-American concepts are increasingly being transplanted. For example, both jurisdictions have taken steps to adopt a law of trusts. However, the underlying fiduciary concept is alien to them.[49]

Taiwan’s company law can thus be traced back to 1929 with the PRC’s Company Law of 1929 (as amended) continuing in force.[50] The German and Japanese models have been influential. Despite some brief US influence on securities laws, the Japanese influence is stronger. Taiwan has also lacked a strong capital market.[51]

Taiwan under Chiang Kaishek had strong public control.[52] The generalissimo thought that China could not compete with the advanced industrial nations. He emphasised the weaknesses of laissez-faire economic theory which made it unsuitable for China. There was a need for protection and planning and thus the emphasis in the 1950s and 1960s was on import substitution and export promotion with strong state influence on the private sector to encourage engagement in value added activities.[53]

By the 1970s, there was a shift to basic industries with extensive government controls which steered the private sector and assisted technology upgrading. In the 1980s, three quarters of exports were high and mid-technology products. This was accompanied by widespread privatisation but within a planned economy.[54]

There has been a tendency for foreigners to think of Taiwan as an economy dominated by small firms which are not catered for particularly well by legislation. The reality is perhaps different, however, and represents more of a symbiosis of public, private, large, small and medium-sized enterprise in a society where law has not been all that significant. Economically the result has been very successful, resulting in 26 of the top 100 firms in Asia (excluding Japan) ranked by market capitalisation being based in Taiwan.[55]

The pervasive pattern of ownership is concentrated in particular family groups by the use of pyramiding and holding companies. The 1997 amendments to the Company Law attempted to deal with affiliated companies but have not been very successful.[56] The Financial Holding Company Law[57] now allows financial holding companies and consolidation of accounts with 90 per cent or more owned subsidiaries.[58] The Taiwanese group as it has evolved has been influenced by the pre-World War Two Japanese zaibatsu and the Korean chaebol.[59]

The pattern of corporate governance has been influenced by family ownership and control of listed companies.[60] Directors and supervisors are often nominees of the owners.[61] Taiwanese law has so far failed to recognise the independence of directors although the law now imposes an express fiduciary duty on them and provides for removal in shareholders’ meetings.[62] Recently restrictions have been imposed on cross-shareholdings.[63] There are now proposals for removing the requirement that directors and supervisors be elected from among the body of shareholders.[64]

The Taiwan Stock Exchange has introduced an independent director requirement in its listing rules but this seems to be mere tokenism. Rule 9 (12) of the Listing Review Rules requires directors and supervisors to act independently and for companies to have at least one independent director as a condition of listing. A definition of independence for this purpose is set out in art 17 of the Supplemental Rules to the Listing Rules. The emphasis, as Lawrence Liu has stated, is linked to status and does not address the evolution towards a broader based network of associates. The listing rules are not particularly effective and there may be a need for a legal requirement.[65]

Directors and supervisors are elected by shareholders in separate elections. Supervisors bear some resemblance to the Aufsichtsrat (supervisory board) of German law but in practice are more similar to the kansaiyku (supervisor) system of Japan. In other words there is no supervisory board as such. Taiwanese boards do not generally have committees.[66] The system of supervisors based on the kansaiyaku and the Aufsichtsrat has not been effective in practice, due to the fact that the supervisors are appointed from the shareholders. This supervisor system may disappear if this requirement is abandoned, and if a stronger system of independent director is adopted.[67]

Taiwan has tended to favour form over substance in corporate law and been rather complacent about reform until recently, with the Council for Economic Planning and Development (‘CEPD’) study[68] and limited reform legislation.[69]

Article 214 of the Company Law allowed actions by shareholders owing 5 per cent of the shares of a company continuously for one year to petition supervisors to sue directors and to bring actions directly if they failed to do so. Private enforcement by shareholder action has not been common in Taiwan’s past, for a variety of reasons. First, there has not been a strong culture of individual rights in Taiwan. Secondly, court procedures based on the civilian model have not facilitated group actions. There is a high cost involved in coordinating a class of plaintiffs. Thirdly court costs are high and the Anglo-Australian cost rule applies. Fourthly, there is no procedure for civil discovery. Lastly, there is a lack of expertise in the judiciary, with members being career judges lacking business experience.[70]

Thus, Taiwan has relied on public enforcement until recently. There has been recourse to criminal proceedings and piggyback civil actions have been brought in tandem with criminal prosecutions.[71] A Securities and Futures Market Development Institute was set up in the early 1980s by the Securities and Futures Commission. It was designed to invest in publicly listed companies and thus has standing. In some respects it acts as a public interest law firm and subsidises private enforcement. Some prominent mass litigation cases have already been brought by the Institute.[72]

As a result of these initiatives, the Securities and Futures Investors Protection Law was recently enacted,[73] which gives formal recognition to the Institute and its work. This law authorises representative actions analogous to the US class action for securities litigation. There is also provision for mediation of such disputes with a controversial ‘cram down’ provision whereby all investors must accept what is approved by the mediation.[74] Reforms of securities laws have pre-empted reforms of the Company Law but now a companies Bill has made a number of piecemeal amendments.

These are significant developments being monitored in both Beijing and Hong Kong. There remains, however, a need for more thorough reform of existing company law and corporate governance, as advocated by the CEPD study. Close attention will no doubt be paid to the recent Consultation Papers reviewing corporate governance in Hong Kong, discussed in the following section.

The British imperial model of corporate law was adopted in Hong Kong and continues to the present time with amendments. Its substantially laissez-faire approach has suited the Chinese family business network system.[76]

When Hong Kong became a British colony in 1843 it received English laws to the extent that they were appropriate to the circumstances of the colony.[77] The first Companies Ordinance in 1865 mirrored the English Companies Act 1862. After this, changes to the imperial model were followed by ordinances in 1911 and 1932. Despite the pressure for reform created by the Company Law Revision Committee set up in 1962, there was a hiatus until 1984 during which only minor amendments were made.[78] No significant legislative initiative in company law was introduced in Hong Kong until the Companies (Amendment) Ordinance 1984. This represented a substantial revision of the law, in line with the United Kingdom’s Companies Act 1948.[79] Following this, a Standing Committee on Company Law Reform (‘SCCLR’) was established, which made a number of recommendations. This led to a number of further amendments, such as the Companies (Amendment) Ordinance 1991 and the Companies (Amendment) Ordinance 1994.

In the mid-1990s, a vast sum was paid for a comprehensive review of the Companies Ordinance (Cap 32) in an attempt to move away from the United Kingdom model to a North American model. In spite of this, the recommendations of the review were largely rejected.[80] The SCCLR has since resumed its work and has recently concentrated on corporate governance reforms.[81]

In the meantime, other bodies have been active in promoting good corporate governance. These include the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd and its wholly-owned subsidiary the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong. Operating in conjunction with these are the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the Hong Kong Society of Accountants, the Hong Kong Institute of Chartered Securities, the Hong Kong Institute of Directors and the Securities and Futures Commission. All of these bodies are driven by the common cause of securing the reputation of Hong Kong.[82]

One of the many challenges Hong Kong faces is how to retain its role as an international financial centre for the Asia-Pacific region.[83] Crucial to this is the need to update its legislation, especially its system of corporate governance. While Hong Kong has been efficient in reforming its system of securities regulation it has faltered in its attempts to reform corporate governance, notwithstanding a plethora of expensive conferences on the topic.

The issues facing corporate governance in Hong Kong were comprehensively canvassed in a recent Consultation Paper[84] produced by the SCCLR. This paper is divided into four parts — Policy, Directors, Shareholders and Corporate Reporting. It has been followed by a further Consultation Paper issued by the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd. Since these represent the most elaborate review of corporate governance in Greater China to date, and are being closely studied by officials in Beijing, we will examine each part in turn.

The SCCLR considered that standards in Hong Kong must be at least commensurate with those jurisdictions of similar international standing including adaptations where necessary to take account of Hong Kong’s unique corporate environment.

This was particularly influenced by three factors. First, because 75 per cent of companies listed on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong are incorporated outside Hong Kong, most provisions of the Companies Ordinance do not apply to them. Thus the listing rules have greater significance in terms of investor protection.[85] Secondly, many of the listed companies have dominant shareholders. This is probably the result of complex patterns of Chinese family business coupled with prior colonisation. The dominant shareholders fall into three main categories: widely held, management-controlled companies; majority-controlled companies; and control through pyramiding structures or cross-shareholdings.[86] (The proportion of shareholders in the first category is greatly outweighed by those in the other two categories.) Thirdly, a lack of shareholder activism[87] raises the issue of the relationship of the listing rules to shareholder rights and remedies, in light of the presence of dominant shareholders.[88]

While these three factors are not unique to Hong Kong they do affect its standing as a dominant international centre. It is surprising that the SCCLR has made no obvious reference to the policy objectives set out in the long title to the New Zealand Companies Act 1993,[89] the Corporate Law Economic Reform Program (‘CLERP’) of Australia[90] or the recent reports of the UK Department of Trade and Industry.[91] Each of these see corporate governance in a broader context which takes into account a number of significant economic factors not mentioned by the SCCLR.

Codification and Restatement

The first question considered by the SCCLR was whether directors’ duties should be codified.[92] They did not see the need to enact the duties for a number of reasons.[93] First, because the finding of a breach of duty would also depend on the complexities of the facts, it would not be possible for all duties to be properly encapsulated in the law. Secondly, as a broad statement of principles would have to framed in very general terms, it would have to be supplemented by detailed guidelines in non-statutory form. Thirdly, a broad statement of principles may not necessarily assist directors to clearly identify the extent of their duties nor would it help directors to determine how they should behave in any given set of circumstances. Fourthly, statutory enactment would tend to be regarded as exclusive, would be inflexible and would not accommodate judicial developments to take into account changing standards. Fifthly, a broad statement of principles is unlikely to provide additional assistance to shareholders. Sixthly, there is no intention to create criminal penalties for breach of directors’ duties generally.

While the last point is a statement of intent, the first five represent bold assertions which are non sequiturs and do not resonate with business people. A statutory statement based on the current Australian wording without adopting the civil and criminal penalty regime, could prove useful to provide guidance to business people in Hong Kong. This need not replace the case law.

Self-Dealing by Directors

Addressing self-dealing by directors involves issues of participation and voting as well as substantive review. The SCCLR proposed four principal amendments.[94] First, the law should clearly set out the general position, being that an interested director should not vote at a board meeting on a matter in which they have an interest. The extent to which the articles of a company should be permitted to allow a director to be exempted from their duty to abstain from voting should be statutorily amended. Exceptions to the general prohibition should be set out in the law. Secondly, sub-s 162(2) of the Companies Ordinance should be amended so that the interested director is required to make a disclosure of his interest on an ad hoc basis in addition to the general notice in advance. This ensures that directors are reminded of the possible conflict of interest and duty of the interested director at the time the proposal is put forward for consideration. Thirdly, contracts, transactions or arrangements in which the director or connected persons have an interest should in any event be disclosed to shareholders. Where these are significant, they should also be referred to the shareholders for their approval. Fourthly, the law should also be amended to clarify the civil consequences of a breach of the general rule.

This is to be contrasted with the two-pronged approach of Australian law and the more lenient approach of Canadian and New Zealand law. The Australian Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) imposes a common disclosure regime and then distinguishes between proprietary companies for whom there is a lenient regime and public companies for whom there is a strict regime.[95] The New Zealand legislation adopts a more lenient approach based on fair value which has led to the extensive use of fair value expert opinions.[96] Canada has followed a similar approach.[97]

Two other dimensions of the self-dealing problem requiring analysis are connected transactions and transactions between the directors or connected parties with an associated company. In relation to the former, the SCCLR recommended shareholder approval for transactions to a requisite value but sought views of the public on the question of fixing an appropriate value.[98] In relation to the latter, the SCCLR recommended approval by disinterested shareholders and extension of the existing listing rules.[99]

Nomination and Election

Practical proposals are made to enhance shareholder participation in the selection of directors and consideration is given to the importance of independent directors although the SCCLR declined to recommend legislation on the latter.[100] This is sensible since no other jurisdiction has done so and all leave the matter to self-regulation.

The SCCLR mainly addressed self-dealing by implementing controls on shareholders and providing relevant remedies.[101] The first cross-referenced the related party proposals. Regarding remedies the SCCLR favoured a statutory derivative action, amendments to the unfair prejudice remedy and clarification of personal rights.[102] To facilitate remedies, a statutory order for inspection was recommended.[103] The SCCLR also envisaged an increased role for the Securities and Futures Commission.[104]

None of these proposals are controversial and all are similar to developments internationally. It is doubtful whether they will be much used by minority shareholders unless the legal system can provide better case management and facilitate alternative dispute resolution as well as adjudication.

Amongst the proposals in connection with corporate reporting are the filing of financial statements by private companies; amendment of the listing rules for more quantitative and forward looking disclosure in management discussion and analysis; dealing with inconsistencies and errors; widening the Financial Accounting Standards Committee and Accounting Standards Committee; setting up a Financial Reporting Review Panel; and improving the monitoring of audit practice.[105] All of these are in line with international developments.

The SCCLR Consultation Paper has now been supplemented by an elaborate Consultation Paper by the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd.[106] The proposed amendments aim to provide more detailed requirements than the law and deal with shareholder protection, directors’ duties and board practices, and corporate reporting and disclosure of information. The directors amendments deal, inter alia, with independent directors, a Code of Best Practice and the establishment of governance committees.

The Consultation Paper states that it is vital to ensure that Hong Kong’s corporate governance is in line with the best international practices. To this end it proposes that the rules should be regularly reviewed and updated in response to changing market conditions and best current market practices in other jurisdictions.

There is a Bill currently before the legislature which makes a number of relatively minor technical reforms to company law.[107] In the meantime, quite apart from reforms of the Companies Ordinance, there have been reforms of securities regulation including the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Cap 571) enacted in March 2002, which updates and extends the law on insider dealing.[108]

It is apparent that while Hong Kong has a credible system of securities regulation it has for various reasons hesitated in the reform of its system of corporate governance. Although opportunities have been lost, the recent Consultation Papers represent a serious attempt at catching up and are being studied closely in Beijing and Taipei. The Consultation Paper of the SCCLR is fairly conservative but is consistent with many international developments. Nevertheless, there is a surprising lack of consideration of the policy behind recent Australasian reforms and the UK proposals.[109] These have something to offer in terms of policy, procedure and substantive reforms. Notwithstanding, the Consultation Paper by Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd is more detailed and accords with international best practice on key matters of corporate governance.

Hong Kong cannot afford to delay reform any longer. As already noted, Taiwan has begun to update its legislation and the PRC seems keen to develop Shanghai as an international financial centre to rival and possibly eventually replace Hong Kong.[110] Historically, from 1949, much of the entrepreneurism of Hong Kong came from Shanghai and there are still old loyalties which exist.[111] A serious attempt is being made to introduce more effective corporate governance in the PRC, especially by greater use of independent directors. There is also a greater sense of professionalism in its regulators. Meanwhile, Hong Kong also faces competition from Singapore, which according to recent surveys, has better systems of corporate governance.[112] Nevertheless, it is likely that in the near future Hong Kong will continue to benefit not only from its status as an international financial centre, but also from the absence of a secure and transparent system of property rights in the PRC. This has been called the ‘property rights arbitrage’.[113] Indeed the PRC has taken advantage of this arbitrage in a number of ways, one example being the expansion of the CITIC Pacific empire.[114] Furthermore, Hong Kong and the PRC now appear to be in a type of symbiotic relationship which will no doubt affect future developments.[115]

A final comment regarding Hong Kong: the imperial model of company law, largely by default, catered tolerably well for the Chinese family business.[116] Future reform must not create too many obstacles in this regard. The PRC does not sufficiently cater for this group at present, and in the past Taiwanese company law did so badly. There are, as Professor Henry Manne wrote over thirty years ago,[117] two corporation systems — the publicly listed corporation and the small incorporated firm — and reformers must ensure that the needs of both are addressed. The tendency of the UK model was to include the latter as an afterthought. This is not a satisfactory approach for the modern law. Improved corporate governance in Hong Kong must pay proper attention to the family business, introducing appropriate safeguards whilst simultaneously ensuring a system which does not stifle the natural talent of the Chinese family business in small firms.

Macao always existed on the periphery of East and West and has been somewhat isolated. Under Portuguese rule, it was noted for gambling and to some extent organised crime. It adopted Portuguese law but has not been a significant commercial centre in recent times.

Now that it has come under the sovereignty of the PRC, attempts are being made to improve its image. It has built an international airport and container port, and is attracting some investment from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan. Nevertheless the fact remains that although it has some banks which advertise on the Internet, the bulk of investment has hitherto been managed out of Hong Kong.

Also, while Portugal is a member of the European Union and subject to its harmonisation program,[119] it has maintained only loose control over the colony. Thus Macao does not seem to have been influenced much by European ideas.

The Chinese business communities in South-East Asia are examined briefly and by way of comparison. These represent communities which were driven out by hostility to business during certain times in China’s history or by the effect of poverty. As business communities in the region they have been remarkably successful.

The most significant group of diaspora Chinese are in control of Singapore, where the company law is based on the Australian uniform Companies Acts,[121] as amended. In spite of a tendency towards nepotism, Singapore manages to project an image of efficiency and good corporate governance and scores well in surveys of the region.[122]

In Malaysia, where company law is also based on Australian legislation, the Chinese community took over from the British as the major investors in listed companies. This continues to the present day in spite of a vigorous bumiputra policy to promote Malay interests.[123] Malaysia has had problems with its corporate governance and was badly affected by the Asian financial crisis.[124] Since then it has engaged in well-publicised initiatives to improve the system. These include the drafting and incorporation of the Malaysian Code of Corporate Governance in the revamped Kuala Lumpur Stock Exchange Listing Rules and the establishment of the Minority Shareholders Watchdog Group Ltd.[125]

Other countries such as Indonesia[126] and Thailand[127] have significant Chinese business presence and ownership. Indonesia languishes as one of the most corrupt corporate governance regimes of Asia although the Chinese interests have managed to cope with this in the past.[128] Corruption cannot be seen merely as an economic phenomenon. It stretches to undermine social cohesion and political legitimacy.[129] Thailand has also suffered as a result of the crisis but has perhaps been more successful in its reforms.[130]

The dominant characteristic in all these countries is the presence of Chinese family business networks reinforced by cross-shareholdings and pyramid structures,[131] coupled with poor disclosure and a general disregard for minority interests. All of these factors have arguably contributed to the so-called Asian eclipse and yet are as resistant to reform as in Taiwan.[132]

Presently, the three main areas of Greater China appear to be poles apart in terms of corporate governance. Can they converge and how might this be achieved?

There are two likely main scenarios. The first is that, given the different stages of development, we shall see in effect a market for corporate laws with each system experimenting in its own way whilst closely observing the others.[133] The second is that, as a result of globalisation and the growth of self-regulation, particularly through the work of the OECD and World Bank, we shall see some degree of convergence through recognition of best practice.[134] Indeed it can be argued that currently we are seeing both occurring with the proposals for independent directors and board committees, although these appear to be reforms of form rather than substance.

At the same time, lurking in the background are unresolved questions of a fundamental nature. The Anglo-American model of corporate governance which seems fundamentally based on a separation of ownership and control (and dominates the OECD and the World Bank approach) is atypical amongst the majority of systems in the world.[135] Family ownership and control which we see in Taiwan, Hong Kong and the rest of South-East Asia are more typical.[136] While President Jiang Zemin has expressed support for separation of ownership and control in SOEs in China,[137] the more important question for the future of Greater China is whether the PRC will take the difficult step of greater recognition of private property rights. This will facilitate the growth of family business in the PRC[138] as well as the separation of ownership and control in SOEs, but perhaps develop an individualist and reactionary tendency. These are obviously difficult steps for the PRC to take but they have the potential, if successful, to unleash unlimited economic growth in the region and make it the dominant economy of the future. It is a little like riding a tiger.

The recent accession of the PRC and Taiwan as members of the WTO[139] represents the beginning of a new economic revolution which will inevitably lead to closer integration in the area.[140] For the first time in its history, the PRC will trade freely with the rest of the world and this must have some impact on its relationship with Taiwan. Membership of the WTO represents a risky and courageous choice for the Chinese leaders as they move away from local protectionism, tight political controls and rampant and spiralling corruption.[141] Developing good corporate governance is an essential step in effecting the required changes. Corporate governance in turn needs a strong legal system and effective bureaucratic structures.[142] This means a move from rule by law to the rule of law, supplemented by other more subtle forms of regulation. Corporate governance has therefore become part of social and political governance but is inevitably the product of individual cultures, determined by the patterns of history as well as economic factors. A contrary and reactionary force in the region which is resistant to change is family control of business, and this provides a serious challenge to the push for reform in all parts of Greater China as well as elsewhere.

Greater China provides a fascinating laboratory for corporate governance as well as posing challenges to Western models. There are many variables operating in a constant state of flux. In a loose sense, Greater China shares a common Chinese cultural inheritance although it is easy to overemphasise this fact. The tendency with an increasing number of Chinese scholars is to downplay this similarity and instead identify differences.[143]

Greater China also exhibits traces of the major legal systems of the world. With the exception of the PRC, it has been characterised by the substantial presence of family business. This puts it outside the Anglo-American paradigm of separation of ownership and control, and resistant to reform, in spite of the fact that Hong Kong operates as an international financial centre. Taiwan has successfully experimented with a public/private mix. The PRC continues to have an economy dominated by public ownership. It lacks a system of private ownership (which is a prerequisite for a free market) and also faces vast challenges in its transition to such a system. Added to this is the historical suspicion of the Western-style corporation and concepts of law and self-regulation. However, the PRC is beginning to experience efficiencies from the separation of ownership and control in SOEs and its reform of corporate governance, while greater recognition of family ownership and control is a problematic further step. At the same time, it has embarked on a steep learning curve, with some surprising openness of mind demonstrated by the leadership, incredible diligence being displayed by leading scholars when absorbing Western ideas in both law and economics, and the latest initiatives of the CSRC. Both Taiwan and Hong Kong are engaged in substantial overhauls of their systems. Taiwan has had a successful managed economy with increasing privatisation and substantial family ownership, but still has a long way to go in developing an effective system of corporate governance. Hong Kong remains a leader but must address an uncertain future.

Just as one can forecast the increasing economic significance of Greater China so one can anticipate that in future, scholars in Greater China will make a major contribution to international scholarship in this field. Currently, in spite of poor library resources in even the leading law schools in the PRC, there are academics and postgraduate students of outstanding ability who are beginning to write significant articles, books and theses in the field of corporate governance strongly influenced by the agency theory of the firm and Western legal ideas.[144] Their contribution, when more easily accessible, may well cause us to rethink not only basic ideas of corporate governance but also our theoretical approaches. Far from the last 10 years representing the end of history[145] with the triumph of the Anglo-American model[146] we may see some revision of our concepts of global capitalism and corporate governance which recognises a spectrum of systems of capitalism and corporate governance.[147] This may also help to resolve some of the apparent contradictions in recent developments, by affirming a concept of political economy characterised by increased private property balanced by strong governance and community,[148] with a greater incidence of family-controlled business under such a regime. Greater China will inevitably play a greater role in the next chapter of this saga.

[*] LLD (London), PhD (Bristol); Professor of Law, Bond University; Professorial Fellow, University of Melbourne. An earlier version of this paper was given at the meeting of the International Academy of Commercial and Consumer Law, held at the Max Planck Institute for Foreign Private and Private International Law, Hamburg in August 2002. The author wishes to thank Say Goo, Ann Carver, Derek Murphy and Lawrence Liu for current information on Hong Kong and Taiwan respectively.

[1] See Daniel Burstein and Arne de Keijzer, Big Dragon, The Future of China: What it Means for Business, the Economy and the Global Order (1999).

[2] See John H Farrar, Corporate Governance in Australia and New Zealand (2001) ch 1. Cf Lu Changchong, Corporate Governance, Contemporary Chinese Forward Economic Series (1999) ch 1.1. For a discussion of the significance of law in corporate governance, see generally Rafael La Porta et al, ‘Investor Protection and Corporate Governance’ (2000) 58 Journal of Financial Economics 3.

[3] See Michael Backman, Asian Eclipse: Exposing the Dark Side of Business in Asia (revised ed, 1999); Jeffrey D Sachs and Wing Thye Woo, ‘A Reform Agenda for a Resilient Asia’ in Wing Thye Woo, Jeffrey D Sachs and Klaus Schwab (eds), The Asian Financial Crisis: Lessons for a Resilient Asia (2000) ch 1; Shang-Jin Wei and Sara E Sievers, ‘The Cost of Crony Capitalism’ in Wing Thye Woo, Jeffrey D Sachs and Klaus Schwab (eds), The Asian Financial Crisis: Lessons for a Resilient Asia (2000) ch 5.

[4] ‘In Praise of Rules’, A Survey of Asian Business, The Economist (London), 7 April 2001, 1.

[5] Richard Eells, The Government of Corporations (1962).

[6] OECD Ad Hoc Task Force on Corporate Governance, OECD Principles of Corporate Governance (1999), <http://www.oecd.org/pdf/M00008000/M00008299.pdf> at 27 September 2002.

[7] Farrar, Corporate Governance, above n 2, ch 34.

[8] See John H Farrar, ‘In Pursuit of an Appropriate Theoretical Perspective and Methodology for Comparative Corporate Governance’ (2001) 13 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 1.

[9] Ibid 3.

[10] Bentham influenced leading politicians of the day and left behind much unpublished material. See Alain Strowel, ‘Utilitarisme et Approche Economique Dans La Theorie du Droit: Autour de Bentham et de Posner’ (1987) 18 Revue Interdisciplinaire D ’Etudes Juridiques 1.

[11] David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1st ed, 1817).

[12] John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy: With Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy (1848).

[13] See S Gordon Redding, The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism (1993).

[14] See Simon Ho and Xu Hai-Gen, ‘Corporate Governance in the PRC’ in Low Chee Keong (ed), Corporate Governance — An Asia-Pacific Critique (2002) 268.

[15] Lawrence S Liu, ‘A Perspective on Corporate Governance in Taiwan’ [2001] Asian Business Law Review, No 31, 22; Lawrence S Liu, ‘Corporate Governance Development in the Greater China: A Taiwan Perspective’ (Paper presented at the Conference on Developing Corporate Governance in Greater China, University of Hong Kong, 2–3 November 2001); Lawrence S Liu, ‘Chinese Characteristics Compared: A Legal and Policy Perspective of Corporate Finance and Governance in Taiwan and China’ (2001) 4 Corporate Governance International Issues 3, 3–4; Lawrence S Liu, ‘Global Markets and Local Institutions: Corporate Law System and Financial Reform Debates in Taiwan’ (2001) (unpublished, copy on file with author); Lawrence S Liu, ‘Simulating Securities Class Actions: The Case of Taiwan’ (2000) (unpublished, copy on file with author).

[16] Edmund Terence Gomez and Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao (eds), Chinese Business in South East Asia: Contesting Cultural Explanations, Researching Entrepreneurship (2001).

[17] Ibid.

[18] See Stijn Claessens, Simeon Djankov and Larry H P Lang, ‘The Separation of Ownership and Control in East Asian Corporations’ (2000) 58 Journal of Financial Economics 81.

[19] Katharina Pistor and Philip Wellons, The Role of Law and Legal Institutions in Asian Economic Development: 1960–95 (1999).

[20] See Yuwa Wei, Comparative Corporate Governance: A Chinese Perspective (PhD Thesis, Bond University, 2002) pts II, IV. Dr Wei’s work represents a substantial contribution to our knowledge of the PRC system and I have learned much from our dialogue during the course of the supervision of her thesis. See also Ho and Xu, above n 14.

[21] The following section is based on John H Farrar, ‘Developing Appropriate Corporate Governance in China’ (2001) 22 Company Lawyer 92.

[22] David Faure, ‘Company Law and the Emergence of the Modern Firm’ in Rajeswary Ampalavanar Brown (ed), Chinese Business Enterprise (1996) vol IV, 263.

[23] Ibid 264. Faure’s explanation of the history of gongsi differs from that of Chinese scholars in that he refers to 19th century usage in Guangzhou.

[24] See generally William C Kirby, ‘China Unincorporated: Company Law and Business Enterprise in Twentieth Century China’ in Rajeswary Ampalavanar Brown (ed), Chinese Business Enterprise (1996) vol IV, 297. Much of the following discussion draws on this chapter.

[25] Issued by the Ministry of Commerce (Shangbu), 21 January 1904.

[26] The Company Law of 1929 (as amended in 1946) continues in force in Taiwan with minor amendments. The economic boom in Taiwan has to some extent been a history of successful small business evading the restrictions of the 1946 law: see below Part III(B).

[27] See On Kit Tam, The Development of Corporate Governance in China (1999); Farrar, ‘Developing Appropriate Corporate Governance’, above n 21; Wei, Comparative Corporate Governance, above n 20; Yuwa Wei, ‘A Chinese Perspective on Corporate Governance’ (1998) 10 Bond University Law Review 363; Harry G Broadman (ed), Meeting the Challenge of Chinese Enterprise Reform (1995); Policy Options for Reform of Chinese State-Owned Enterprises, World Bank Discussion Paper WDP335 (1996); China’s Management of Enterprise Assets: The State as a Shareholder, World Bank Economic Report No 16265 (1997); Nicholas R Lardy, China’s Unfinished Economic Revolution (1998); World Bank, China: Weathering the Storm and Learning the Lessons, Country Economic Memorandum (1999); Xinqiang Sun, ‘Reform of China’s State-Owned Enterprises: A Legal Perspective’ (1999) 31 St Mary’s Law Journal 19; Harry G Broadman, ‘China’s Membership in the WTO and Enterprise Reform: The Challenges for Accession and Beyond’ (2000), <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id =223010> at 20 August 2002.

[28] Broadman, ‘China’s Membership in the WTO’, above n 27, 1.

[29] See Yuwa Wei, Investing in China: The Law and Practice of Joint Ventures (2000) ch 1.

[30] Broadman, ‘China’s Membership in the WTO’, above n 27, 2.

[31] For an interesting early study see Willy Kraus, Private Business in China: Revival Between Ideology and Pragmatism (Eric Holz trans, 1991 ed) 102 ff; James M Ethridge, China’s Unfinished Revolution (1990) 146–8.

[32] Broadman, ‘China’s Membership in the WTO’, above n 27, 3.

[33] See Ho and Xu above n 14, 273. For the practical difficulties facing private enterprise, see Joe Studwell, The China Dream (2002) 228–31. These include registered capital requirements that are among the highest in the world. Studwell cites a survey of start-up bureaucracy by Harvard University that ranked the PRC 51st for delay and 43rd for cost, out of 75 developing nations in 2000. There are many permits needed.

[34] Amendments to the Constitution of the People’s Republic Of China, adopted at the Second Session of the Ninth National People’s Congress on 15 March 1999.

[35] Company Law of the People’s Republic of China, adopted at the Fifth Meeting of the Standing Committee of the Eighth National People’s Congress on 29 December 1993 (entered into force 1 July 1994). See Guiguo G Wang and Roman Tomasic, China’s Company Law: An Annotation (1994).

[36] See Wei, Investing in China, above n 29.

[37] Similar to those in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 1324.

[38] Law of the People’s Republic of China on Civil Procedure, adopted at the Fourth Session of the Seventh National People’s Congress on 9 April 1991 (entered into force 9 April 1991).

[39] See generally Wei, Investing in China, above n 29.

[40] See Broadman, ‘China’s Membership in the WTO’, above n 27.

[41] Securities Law of the People’s Republic of China, adopted at the Sixth Meeting of the Standing Committee of the Ninth National People’s Congress on 29 December 1998 (entered into force 1 July 1999).

[42] For a somewhat optimistic view, see Carl E Walter and Fraser J T Howie, ‘To Get Rich is Glorious!’ China’s Stock Markets in the ‘80s and ‘90s (2001). See President Jiang Zemin’s speech in praise of the separation of ownership and control and the argument that socialism can also utilise it, reproduced in Jiang Zemin, On the ‘Three Represents’ (2001) 195.

[43] For an interesting recent study, see Weiying Zhang, ‘China’s SOE Reform: A Corporate Governance Perspective’ (2001) (unpublished, copy on file with author). Cf Jiang Zemin, ‘Issues to be Correctly Handled in Current Economic Work’ in Jiang Zemin, On the ‘Three Represents’ (2001) 105.

[44] See above n 27.

[45] CSRC, Guidelines for Introducing Independent Directors to the Board of Directors of Listed Companies (2002).

[46] CSRC, Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Companies (2002).

[47] See generally A P L Liu, ‘The Political Basis of the Economic and Social Development in the Republic of China 1949–80’ (Occasional Papers in Contemporary Asian Studies No 1, University of Maryland, 1985); Chi-Nien Chung, ‘Markets, Culture and Institutions: The Emergence of Large Business Groups in Taiwan: 1950s–1970s’ (2001) 38 Journal of Management Studies 719; Liu, above n 15. Much of the coverage of Taiwan in this article is based on the work of Lawrence Liu.

[48] Liu, ‘Chinese Characteristics Compared’, above n 15, 11.

[49] Ibid. See also Michael I Nikkel, ‘“Chinese Characteristics” in Corporate Clothing: Questions of Fiduciary Duty in China’s Company Law’ (1995) 80 Minnesota Law Review 503.

[50] Company Law, promulgated on 26 December 1929 (entered into force 1 July 1931), amended on 12 April 1946, 19 July 1966, 25 March 1968, 11 September 1969, 4 September 1970, 9 May 1980, 7 December 1989, 10 November 1990, 25 June 1997, 15 November 2000, 12 November 2001.

[51] Liu, ‘Global Markets and Local Institutions’, above n 15.

[52] See Peter Nolan, China and the Global Economy (2001) 11.

[53] Ibid 12.

[54] Ibid 11–13.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Liu, ‘Global Markets and Local Institutions’, above n 15.

[57] Financial Holding Company Law of Taiwan, promulgated on 9 July 2001 (entered into force 1 November 2001).

[58] Liu, ‘A Perspective on Corporate Governance in Taiwan’, above n 15, 2.

[59] Ibid 3.

[60] Liu, ‘Chinese Characteristics Compared’, above n 15, 6.

[61] Liu, ‘A Perspective on Corporate Governance in Taiwan’, above n 15, 4, 10.

[62] Arts 23, 199. See also Chi-Hsien Lee, ‘Corporate Governance in Taiwan: Recent Developments in Governmental Policy — A View from Government’ (Paper presented at the Conference on Developing Corporate Governance in Greater China, University of Hong Kong, 2–3 November 2001) 16 ff.

[63] Art 167.

[64] See Council for Economic Planning and Development (‘CEPD’), Corporate Law Study of 1999–2000 (2000). The research was conducted by Lee and Li (a leading law firm in Taiwan) and the Asia Foundation in Taiwan. Professor Lawrence Liu, a distinguished corporate lawyer and partner in the firm, led the research team and has been prominent in the formulation of reforms.

[65] Liu, ‘A Perspective on Corporate Governance in Taiwan’, above n 15, 4.

[66] Ibid 5.

[67] Ibid.

[68] CEPD, above n 63.

[69] See Liu, ‘Global Markets and Local Institutions’, above n 15, for a detailed discussion.

[70] See Liu, ‘A Perspective on Corporate Governance in Taiwan’, above n 15, 11.

[71] Ibid 16. See Liu, ‘Simulating Securities Class Actions’, above n 15, 6.

[72] See the nine examples provided by Liu, ‘A Perspective on Corporate Governance in Taiwan’, above n 15.

[73] Ibid 11; Liu, ‘Simulating Securities Class Actions’, above n 15.

[74] Liu, ‘A Perspective on Corporate Governance in Taiwan’, above n 15, 21.

[75] The following is based on John H Farrar, ‘A Critical Analysis of the Standing Committee’s Corporate Governance Proposals’ (Speech delivered at the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission, Hong Kong, 12 November 2001). See generally Chris Patten, East and West (1999); Robert Fell, Crisis and Change: The Maturing of Hong Kong’s Financial Markets (1992).

[76] P Lawton, ‘Directors’ Remuneration, Benefits and Extractions: An Analysis of their Uses, Abuses and Controls in the Corporate Governance Context of Hong Kong’ (1995) 4 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 430, 434–6.

[77] Peter Wesley-Smith, The Sources of Hong Kong Law (1994) 85–201.

[78] Philip Smart, Kevin Lynch and A Tam, Hong Kong Company Law, Cases, Materials and Comments (1997) 9 ff.

[79] Ibid 10–11.

[80] See E L G Tyler, ‘Background to Hong Kong’s Companies Legislation and the Review’ (1995) (unpublished, copy on file with author); Philip Smart, ‘Companies Legislation in Hong Kong: Present and Future’ (1997) 18 Company Lawyer 34.

[81] See Betty May-foon Ho, Public Companies and their Equity Securities: Principles of Regulation Under Hong Kong Law (1998) 1A pt III; Hong Kong Standing Committee on Company Law Reform (‘SCCLR’), Corporate Governance Review by the Standing Committee on Company Law Review (200 1).

[82] See Smart, Lynch and Tam, above n 78, 15; J Mark Mobius, ‘Corporate Governance in Hong Kong’ in Low Chee Keong (ed), Corporate Governance — An Asia-Pacific Critique (2002) 204–5.

[83] See Fell, above n 75; Mobius, above n 82, 204–5.

[84] SCCLR, above n 81.

[85] Ibid.

[86] Ibid 4.

[87] Ibid 3.

[88] Ibid 5.

[89] The long title to the Companies Act 1993 (NZ) states that it is an Act to reform the law relating to companies, and, in particular:

(b) To provide basic and adaptable requirements for the incorporation, organisation, and operation of companies;

(c) To define the relationship between companies and their directors, shareholders and creditors;

(d) To encourage efficient and responsible management of companies by allowing directors a wide discretion in matters of business judgment while at the same time providing protection for shareholders and creditors against the abuse of management power; and

(e) To provide straightforward and fair procedures for realising and distributing the assets of insolvent companies.

[90] See Robert Baxt, Keith Fletcher and Saul Fridman, Afterman and Baxt’s Cases and Materials on Corporations and Associations (8th ed, 1999) 173 ff. The Australian Corporate Law Economic Reform Program (‘CLERP’) is well-intentioned and pursues fundamental economic principles such as market freedom, investor protection, information transparency, cost effectiveness, regulatory neutrality and flexibility and business ethics and compliance. Whilst the Australian policy is sound, its implementation is problematic, lacking a coherent modus operandi. It is based on a plethora of piecemeal reforms and an overly technical drafting style: see Farrar, Corporate Governance, above n 2.

[91] See The Company Law Steering Group, Modern Company Law for a Competitive Economy, Final Report URN 01/942 and URN 01/943 (2001), and the earlier reports referred to therein.

[92] SCCLR, above n 81, 15–16. Restatement in statutory form has taken place in Canada and New Zealand although there is a lack of clarity about the relationship with the case law. Australia has retained the case law but has statutory duties which replicate them substantially but for a different purpose, namely civil and criminal penalties. The relationship is, however, made clear in the legislation: Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 185.

[93] Ibid.

[94] Ibid 16.

[95] Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ss 19 1–5.

[96] Companies Act 1993 (NZ) ss 139–1 42.

[97] See generally, Farrar, Corporate Governance, above n 2, ch 12.

[98] See SCCLR, above n 81, 18.

[99] Ibid.

[100] Ibid 40 ff.

[101] Ibid ch 3.

[102] Ibid 50 ff.

[103] Ibid 70.

[104] Ibid 74.

[105] Ibid ch 4.

[106] Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Ltd, Proposed Amendments to the Listing Rules Relating to Corporate Governance Issues (2002), <http://www.hkex.com.hk/library/listpaper/Corporate%20governance%20issues.pdf> at 26 July 2002.

[107] Companies (Amendment) Bill (2002).

[108] See Smart, Lynch and Tam, above n 78, for a discussion of the old law.

[109] See above nn 89–9 1 and accompanying text.

[110] See Michael J Enright, Edith E Scott and David Dodwell, The Hong Kong Advantage (1997) 264–7.

[111] See Gary Hamilton (ed), Cosmopolitan Capitalists: Hong Kong and the Chinese Diaspora at the End of the 20th Century (1999).

[112] ‘In Praise of Rules’, above n 4.

[113] Barry Naughton, ‘Between China and the World: Hong Kong’s Economy Before and After 1997’ in Gary Hamilton (ed), Cosmopolitan Capitalists: Hong Kong and the Chinese Diaspora at the End of the 20th Century (1999) 80, 80–1.

[114] Ibid 85 ff.

[115] Ibid 89.

[116] It allowed considerable freedom and flexibility. For a contrary view (unsupported by evidence) see Enright, Scott and Dodwell, above n 110, 216–7. This no doubt reflects the US background of two of the authors.

[117] Henry G Manne, ‘Our Two Corporation Systems: Law and Economics’ (1967) 53 Virginia Law Review 259.

[118] See Austin Coates, Macao and the British, 163 7–1842: Prelude to Hong Kong (1988); Jonathan Porter, Macau, The Imaginary City: Culture and Society, 1557 to the Present (1996).

[119] See Richard Thomas (ed), Company Law in Europe (2002) Division L.

[120] See East Asia Analytical Unit, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Overseas Chinese Business Networks in Asia (1995).

[121] These were adopted by all Australian States and Territories between 1961 and 1962: Companies Act 1961 (NSW); Companies Act 1961 (Vic); Companies Act 1961 (Qld); Companies Ordinance 1962 (ACT); Companies Act 1961 (WA); Companies Act 1962 (Tas); Companies Act 1962 (SA); Companies Ordinance 1963 (NT).

[122] See Kala Anandarajah, Corporate Governance — A Practical Approach (2001).

[123] See John H Farrar, ‘Corporate Governance or Social Governance — Which Way Forward?’ (Speech delivered at the Malaysian Institute of Corporate Governance Lecture, Kuala Lumpur, 16 April 2001).

[124] See Edmund Terence Gomez and Kwame Sundaram Jomo, Malaysia’s Political Economy — Politics, Patronage and Profits (2nd ed, 1999).

[125] See Malaysian Institute of Corporate Governance, Malaysian Code of Corporate Governance (2001); Dato Megat Mijmuddin Khas, Low Chee Keong and Kala Ananderajah, ‘Corporate Governance in Malaysia’ in Low Chee Keong (ed), Corporate Governance — An Asia-Pacific Critique (2002) 225; Aiman Nariman Mohd Sulaiman, Directors’ Duties and Corporate Governance (2001).

[126] See Stephen C Radelet and Wing Thye Woo, ‘Indonesia: A Troubled Beginning’ in Wing Thye Woo, J D Sachs and K Schwab (eds), The Asian Financial Crisis: Lessons for a Resilient Asia (2000) ch 8.

[127] See Frank Flatters, ‘Thailand and the Crisis: Roots, Recovery and Long Run’ in Wing Thye Woo, J D Sachs and K Schwab (eds), The Asian Financial Crisis: Lessons for a Resilient Asia (2000) ch 12.

[128] See also Radelet and Woo, above n 126.

[129] See Adam Schwartz, A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia’s Search for Stability (2nd ed, 1999) 316–9, 519; Tim Lindsey and Howard Dick (eds), Corruption in Asia: Rethinking the Governance Paradigm (2002) chh 5–6; Flatters, above n 127.

[130] See also Schwartz, above n 129.

[131] See East Asia Analytical Unit, above n 120, ch 8. See also Cally Jordan, ‘Family Resemblances: The Family Controlled Company in Asia and its Implications for Law Reform’ (1997) 8 Australian Journal of Corporate Law 89.

[132] See Backman, above n 3.

[133] See Yuwa Wei, ‘Developing a Common Model of Corporate Governance for Greater China’ (Paper presented at the Conference on Developing Corporate Governance in Greater China, University of Hong Kong, 2–3 November 2001) 22.

[134] See John H Farrar, ‘The New Financial Architecture and Effective Corporate Governance’ (1999) 33 The International Lawyer 927; John C Coffee Jr, ‘The Future as History: Prospects for Global Convergence in Corporate Governance and its Implications’ (1999) 93 Northwestern University Law Review 641; L A Cunningham, ‘Commonalities and Prescriptions in the Vertical Dimension of Global Corporate Governance’ (1999) 84 Cornell Law Review 1133.

[135] Rafael La Porta, Florencio López-de-Silanes, Andrei Scheifer, ‘Corporate Ownership Around the World’ (Working Paper 6625, National Bureau of Economic Research, 1998).

[136] See Redding, above n 13. See also Claessens, Djankov and Lang, above n 18.

[137] See Jiang Zemin, above n 42.

[138] See Kraus, above n 31.

[139] See Supachai Panitchpakdi and Mark L Clifford, China and the WTO (2002). See also Yang Jen, Managing Non-Participation: Taiwan as an International Trader (2001) for a historic background.

[140] See Yang Jen, above n 139, 278 ff.

[141] Ibid 140. The extent of the corruption was recognised by President Jiang Zemin, ‘Promote the Development of the Party’s Work Style, the Building of a Clean Government, and the Fight Against Corruption’ in Jiang Zemin, On the ‘Three Represents’ (2001) 118.

[142] Ibid 147.

[143] See, eg, Gomez and Hsin-Huang Hsiao (eds), above n 16, 36–7.

[144] Based on the author’s experiences visiting Peking University; University of International Business and Economics; Soochow University, Suzhou and Taipei; and the University of Hong Kong since 1998, and supervising Chinese postgraduate students in Australia. See the citations to various Chinese materials in Wei, Comparative Corporate Governance, above n 20; Lu, above n 2.

[145] See Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (1992).

[146] Holger Hansmann and Reinier Kraakman, ‘The End of History for Corporate Law’ (2001) 89 Georgetown Law Journal 439. Cf Douglas M Branson, ‘The Uncertain Prospect of Global Convergence in Corporate Governance’ in Low Chee Keong (ed), Corporate Governance — An Asia-Pacific Critique (2002) ch 15.

[147] Cf Robert Heilbroner, Twenty-First Century Capitalism (1993) 113; Charles Hampden-Turner and Fons Trompenaars, The Seven Cultures of Capitalism (1993).

[148] Cf Barry Clark, Political Economy — A Comparative Approach (2nd ed, 1998) 318 which analyses the interaction of market, government and community. This is not an argument for communitarianism as such, but more one for a system of corporate governance which includes an ethic of social responsibility. As Confucius said, ‘wealth and rank attained through immoral means have as much to do with me as passing clouds’: Confucius Kongfuzi, The Analects (1979) VIII, 16. Francis Fukuyama has argued ‘the reduction of trust in a society will require a more intrusive, rule-making government to regulate social relations’: Francis Fukuyama, Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity (1995) 36. President Jiang Zemin refers to the necessity for the private sector to stand behind party policies, obey the law, be considerate of the workers and guarantee their rights and make due contributions to the state and society: Jiang Zemin, ‘Issues to be Correctly Handled’, above n 43.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UNSWLawJl/2002/29.html