University of Technology, Sydney Law Review

|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

University of Technology, Sydney Law Review |

|

The objective of all online statute and case databases is to make the law available to those who want it.

The novelty of providing databases over the internet is that for the first time there is a convenient and affordable (usually free) means for lay users to have direct access to the laws that might affect them. Although the creation of looseleaf publications greatly facilitated the determination of the current law, those publications were, except from public libraries, largely unavailable to lay users, and even to modest-sized law firms, because of their expense. More affordable prints of individual enactments were often out of date. Not only is access to law databases made easy through internet connections, but word, phrase, proximity and Boolean searches make finding the relevant laws easier for the lay user. This convenience and economy has led to an increasing tendency for lay users to seek direct access to legal information. It is an unfortunate fact that the hiring of legal professionals has become prohibitively expensive for many genuine disputes that have low monetary value. While convenient access to statutory law over the internet may not provide a fully satisfactory substitute for professional legal advice, it is a worthwhile improvement for many citizens.

With access to the law made easier and plain language initiatives to make it more readily understandable, we might expect that public knowledge of the law would increase. With that increased knowledge, greater compliance with the law may be achieved. This easy and cheap access to the law might also encourage the use of IT among legal professionals, leading to more efficient and less costly services for their clients.

In the case of Hong Kong, by making the law more accessible to the international legal, commercial and academic communities, the message that Hong Kong continues to be a jurisdiction ruled by law can be reinforced. China’s acceptance into the World Trade Organisation is expected to attract further interest in Hong Kong and its more familiar legal system.

The benefits of online law databases include:

• virtually instant access to current law, compared to looseleaf and bound publications

• the ability to copy material from databases and paste it into documents

• reductions in the cost of purchasing, updating and storing paper publications

• less reliance on out of date versions of the law

• easier preparation of new or amended legislation through the use of search functions and text copy and paste

• the ability to view the law at a past date, thereby assisting prosecutions

• increased ease and accuracy for government departments in advising the public about the laws that they administer.

The BLIS database includes the following material:

• legislation (ordinances and regulations)

• constitutional documents (basic law, People’s Republic of China laws applicable to Hong Kong, UK laws at 30 June 1997 etc)

• bilingual glossary of legal terms used in legislation

• international agreements: bilateral—contents; multilateral—list only for now

• guide to bilingual interpretation

• English subject index to Ordinances

• guide to “Is it in operation?”

BLIS is unique because it is bilingual (English/Chinese), with both traditional and simplified Chinese characters, and is able to switch directly between English and Chinese sections. The data is organised at the “section” level, not at the level of the whole enactment, thus providing a number of advantages: quick and easy access directly to individual sections, and retention of sections as they were before amendment. However, it is awkward to view, download, and print whole enactments. BLIS is rapidly updated—there is an average two week delay after amendments come into force. Pending changes are marked each day, thus giving reassurance that without the pencil mark, the section is up to date as of the previous day. Advanced searches for cross references, definitions, and searches within selected enactments are possible. Finally, users are able to access the law as it was at any date after 29 June 1997.

Since BLIS went online in November 1997, the site has had over 1.4 million visits and is now averaging 55,000 visits per month. These numbers exclude the Department of Justice staff (the most intensive users) and other Hong Kong government departments, which have access via an intranet facility.

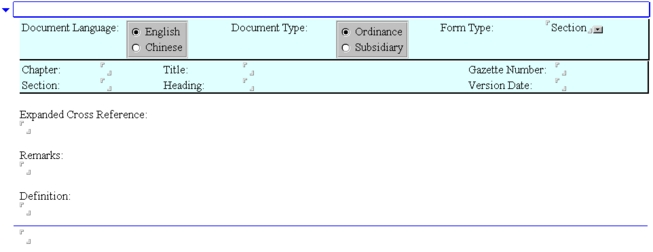

[insert graphic from CD]

The Department of Justice frequently receives requests for permission to copy data and link to its database. We recently reviewed our basic policies in this regard and have provided guidance on our main page so that users can, in non-commercial cases, determine what may be done without contacting the Department. Our policy is set out as follows; for the full text, refer to our website under the heading “Yes, you may copy and link, but . . .”—

(a) It is the policy of the Government that the electronic publications of the laws of Hong Kong should be freely available to all persons.

(b) Visitors to this website are permitted to—

i. download, print, make copies of and distribute all information on this site, and

ii. include information on this site in a text book or other educational materials, whether in electronic or paper form.

(c) However, except as allowed under paragraph (d), permission is required from the Department of Justice to sell, or sell access to, information on this site.

(d) Permission is not required to charge reasonable fees for the making of paper copies of information on this site for others.

(e) Care should be taken to ensure that any copies made are accurate and up to date. In particular, copies previously made of BLIS data should not be re-copied or distributed without checking the BLIS site to see if there have been any amendments since the copies were first made.

(f) Anyone may link to the main page of this site, but may not charge for facilitating that specific access, even though charges may be imposed for accessing the site on which our link is contained.

(g) The Department of Justice does not object to the linked BLIS pages appearing within frames of other sites. However, care should be taken to ensure when using frames that the origin of the BLIS content is not misrepresented. Also it should be made clear that access to the BLIS data is free and available directly from the BLIS website. If the BLIS data is filtered through a script it must not modify the BLIS page and logos and the text must remain intact.

(h) There are practical and technical difficulties in making links to specific enactments within BLIS. Persons who want to establish such links should contact the Department of Justice at the mail address shown on this site.

(i) Where any of the contents of this site are re-published as part of another publication, a statement to the effect that the extract was ‘reproduced from the Bilingual Laws Information System website [www.justice.gov.hk] with the permission of the Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region’ must be included.

Hong Kong has not yet given legal status to BLIS and we are considering the issue for the future once we perform a major site upgrade planned for 2002–03. We are aware of the Tasmanian (and more recently, the Australian Capital Territory) example of giving authenticity to its database, and we will be exploring that option as well as the approach of giving it prima facie effect, as is done with our looseleaf publication. Unlike many other government legislation sites, we have not issued a blanket disclaimer of liability for any errors of content. It seems highly inappropriate for governments not to bear responsibility for ensuring the accuracy of their published laws, in whatever format. Nevertheless, we do caution users to check the authentic versions of the laws for matters of great importance.

For the time being, we advise users—

(a) Although BLIS is an official government publication, it does not have legal status.

(b) The Department of Justice takes great care to achieve accuracy in the content of BLIS.

(c) However, users should be particularly wary of the possibility of tab and indent differences due to the limitations of the hypertext mark-up language (HTML).

(d) The simplified Chinese character version of BLIS is provided by an automatic online translation program. The translation process may not be entirely accurate. Check against the traditional character version of BLIS if in doubt.

(e) Any difference that is detected between BLIS and the Loose-Leaf Edition of the Laws or the Government Gazettes will be resolved by law in favour of those printed publications. Therefore, for matters of great importance to users, reference to the Loose-Leaf Edition of the Laws or the Government Gazettes should be considered.

Although the basic policy is to facilitate the widest possible access to the laws, there is still scope for claiming our copyright protections. We need to take reasonable measures to protect the integrity of the publication, ie to ensure that copies are accurate and up-to-date. Therefore we make it clear that any permission we give can be withdrawn should it come to our attention that there is a pattern of such abuse. On the site, we state the authority for our copyright and expressly state that the permission granted to link, download, print, make copies of and distribute all information on the site may be withdrawn at any time.

Before the internet version of BLIS, we had made access to the database available via a third party for what we thought was a reasonable charge to defray the cost of modems etc. However, it turned out that the charging of any fee was almost a complete deterrent to access. We had no more than 23 fee-paying subscribers outside of government, and this eventually fell to less than ten law firms out of a population in Hong Kong of 5000 legal practitioners. We of course had no requests for subscription from the general public.

It would cost government more to charge fees than to not charge fees. It is unrealistic to expect that any amount of fees that could be recovered by government would come close to the direct costs that would be necessarily incurred to set in place the mechanism for their recovery. We would have incurred the costly effort of tendering, settling the contractual arrangements, contract supervision, accounting and audit control.

Governments everywhere pronounce their commitment to making the laws more accessible to the people. Governments now have the means, via the internet, to deliver published laws quickly, easily and economically to anyone who owns or has access to a computer. However, except for a limited number of professionals and corporations, that goal would be unattainable if fees were charged for access. Few (if any) infrequent users, whether non-professionals or overseas journalists or academics, would go to the trouble of subscribing to a commercial service for only occasional research.

Governments spend enormous amounts of money to produce new laws. Only a few dollars more can deliver the law via the internet to the people affected. It is worth reflecting on the fact that every year governments spend millions of dollars to formulate, process, draft, enact and publish laws. Simply add up the salary, space and related costs of the law drafters and all other officials who participate in the process, including the legislative members and staff. The ultimate objective of all of that expenditure is to require people or corporations to behave, or not behave, in a certain way. That objective cannot be achieved unless knowledge of the law is communicated to affected persons. Even though ignorance of the law is not a defence in our system of justice, it surely should not relieve government of a moral obligation to do its best to inform the public about its laws. Spending an additional relatively paltry amount to make the laws freely available over the internet would appear to be money well spent if it succeeds even partially in meeting that obligation.

As a practical matter, there is no way to detect whether one site has added links to another. We only know if this happens if we are told about it, usually by the site owner, who may ask for permission. We decided to make it clear on the site that that no permission is required if the request is to link to our main page. However, sites that provide links directly to specific enactments, bypassing the main page, are cause for concern because users will miss critical information on the main page about how up to date it is, the explanation of pending changes mark, information on permission to copy, guides to using BLIS, special announcements and so on.

We are sometimes asked to provide soft copy versions of specific BLIS enactments from an organisation that wants to make them available on its network or site. The problem with this is that if enactments are later updated, the soft copy versions may become out of date. When we are asked for permission (permission is not required pursuant to our notice unless fees are charged), we request the posting of a disclaimer and the addition of advice about the value of visiting BLIS regularly to check for announcements and amendment status.

At present we have a contract with Butterworths Asia Ltd (for the Lexis-Nexis service) and are in the process of negotiating with Sweet & Maxwell. Each carries or will carry a copy of BLIS and will remit standard royalty rate amounts to us as a data provider. It may seem inconsistent in terms of providing free access to the law to charge fees. However, we take the view that these services are frequented by a certain sector of the community (lawyers), and if it is convenient for them to do all of their research within one environment, we should not inhibit it. Nevertheless, we entered into the arrangement subject to the inclusion of the following text in a prominent location so that users would be aware of the government’s copyright, the existence of BLIS on the internet and that the government assumed no responsibility for the accuracy of the publication.

When we established the first version of BLIS in 1989, we were constrained in our choice of software because of the need to include the Chinese language. Currently, BLIS is contained in a Lotus Notes database. By using the Lotus Domino Server, we were able to easily provide our internal database to internet users.

Because we organised our data at the “section” level, not at the level of the whole enactment, there is no convenient way for users of conventional internet browsers to download or print whole enactments from the Notes database. This was not a problem for the staff in the Hong Kong Department of Justice, because we use the native Lotus Notes client software as the interface to the database. This enables the easy selection of multiple documents for downloading and printing. internet users could also have this facility by installing Lotus Notes client software on their PC, but that is not a solution that attracts much interest. Our current project to upgrade BLIS is looking at this problem.

In terms of data collection and transfer, the law drafters use MS Word, as do their client departments. The Government Printer who prints Bills and the enacted legislation uses Macintosh workstations and Quark Express software. The BLIS database uses Lotus Notes, from which most people copy material back into MS Word for use as a precedent and/or in opinion advice. Hand mark-up of printed copies is still used for minor changes between drafters and the printer and the printer strips in changes to the hard copy, thus destroying the integrity of the soft copy. All participants agree that it is a hugely inefficient system, but agreeing on solutions is not easy.

Finally, there is still no solution for alerting users to amendments not yet in force. It has become an irreversible trend in many jurisdictions to have deferred commencement of provisions after they are enacted, usually to allow for preparation of related regulations, administrative support or simply to allow time for publicity. This poses a problem for both looseleaf and database publications. The time delay between enactment and commencement may be a matter of days, months or even longer. If there is only a short delay, there is often insufficient time to note the pending change before the actual change (and consequent removal of the note) occurs. This consumes staff resources and adds little to the benefit of end users. In Hong Kong, we have so far concluded that any attempt at alerting users to amendments not yet commenced (with a note in the affected section) is not worth the effort.

We have identified several ways to improve the BLIS service. The following are items to be considered for inclusion in the BLIS upgrade project that should be completed in the latter half of 2002. The aim is to:

(a) enable continuous viewing, downloading or printing of a whole ordinance or a selection of sections within an ordinance using common browsers;

(b) enable subscription notification of changes to any specified enactment(s);

(c) develop a context print function so that a user can print only the relevant extracts from enactments (the line on which the search term appears plus the lines above and below);

(d) enable properly formatted viewing on Personal Digital Assistants, phones, etc;

(e) provide hyperlinking—

i. within and between enactments for easy navigation;

ii. to and from individual sections for use by other departments for legislative guidelines/codes of practice and web-published information brochures;

iii. to the electronic publication of legislation as enacted;

iv. to the text of multilateral agreements.

(f) facilitate creation of a Table of Contents and making it printable and downloadable;

(g) make cosmetic and navigation improvements;

(h) offer publishing in CD-ROM format “on-demand” in various formats as requested and if feasible;

(i) giving legislative authenticity to BLIS.

For information on BLIS hardware and software configuration, and on BLIS editorial policies, workflow, procedures and stff, see Appendices 1 and 2.

Hong Kong has 42 volumes of bilingual looseleaf laws. New and amended primary and subsidiary legislation is enacted throughout the year. The looseleaf was established in 1991. We knew from experience in other jurisdictions that if we attempted to publish replacement pages for the whole set at once, using one cut-off date, publication would be seriously delayed. Instead, we chose to prepare all available amendments to a particular enactment, and then print the pages. If further amendments occur for a particular enactment before distribution, the amendments wait for the next edition. In this way we have eliminated the problem of catch-up for amendments to enactments in the whole set.

To enable readers to determine how current an enactment is, we provide an instruction sheet/checklist for each enactment, and an instruction sheet/checklist for the whole set. Each page of the looseleaf edition bears an issue number. By referring to the pink checklist and instructions for a particular piece of legislation or instrument, the user can determine whether that page corresponds to issue number given in the pink checklist. There is also a blue master checklist and instructions. This tells the user whether the various pink checklists are, or remain, up to date.

Thus, to find out if a page of text is up to date, the user—

• notes the issue number of that page of text;

• refers to the pink checklist for the particular piece of legislation or instrument to see if the page of text bears the issue number required by the pink checklist; and

• checks the blue master checklist to make sure the pink checklist is the correct one.

The checklists are prepared in camera ready format using MS Word, so that the final offset printing is not delayed by the preparation of further proofs. By dealing with each enactment only once during a publication cycle, users can receive updated pages sooner and more frequently (we distribute every four to six months) than otherwise, and can quickly determine whether a particular enactment is up to date.

This technique of focusing on the individual enactment has been taken one step further with the advent of BLIS, which makes amendments to particular sections and adds edit pencil marks to indicate if there are any outstanding amendments not yet incorporated. The result is a database that is up to date at least as of the previous day.

[insert graphic from CD]

BLIS Hardware and Software Configuration

BLIS consists of Lotus Notes databases. They are the BLIS Editor Database (2GB size, 128k documents), Reader Database (1.6GB size, 128k documents), the Chinese-English Glossary (0.3GB size, 34k documents) and the English-Chinese Glossary (0.5GB size, 74k documents).

The existing BLIS Internal System runs on Domino 4.66B on an HP-UX 11 platform with eight 4-GB hard disks. Editors input data into the Editor Database which is replicated twice a day to the Reader Database in the same server. About 1000 users within the Department of Justice use the Reader Database to browse and search the Laws of Hong Kong via Notes Client Release 4 on their PCs.

The gateway server is used for handling data replication. It is an HP-UX 11 platform with four 4-GB hard disks. Data is replicated daily from the Reader Database of the BLIS Internal System into the gateway server. The Database is then replicated to the web server and the replicator server.

The web server runs on Domino 4.66B on a Windows NT SP5 platform with one 4GB and one 2GB hard disk. Internet users can browse the database with common web browsers. They can also use Notes Client 4.6 to access the database to make use of additional functionality available to Notes Client only.

There is also a replicator server on a Chinese Windows NT platform which is used for replicating data to other servers in government bureaus and departments via the government network (GNET). Current replication recipients include the Judiciary, the Works Bureau, the Inland Revenue, the Buildings Department and the Cyber Central Government Offices (government intranet).

There is also a Simplified Chinese Server on a Windows 2000 SP2 platform connected to the web server. It acts as a translation server to translate the BLIS content into simplified Chinese to facilitate mainland web users to use BLIS on the internet.

Note that the original development of BLIS onto the Notes platform for internal use (ported from Wang) cost about AUD$1.1 million at current exchange rates. Making BLIS available on the internet cost about $600,000. These figures exclude the time spent by internal staff who worked with the contractors.

BLIS Editorial Policies, Workflow, Procedure, Work Priorities and Staff

1) For documents with retroactive effect,

(a) we will create a version dated back to the commencement date;

(b) we will add the sentence “Adaptation amendments retroactively made—see ….” in the Remark field to those versions with a later commencement date but have been published before the “Adaptation Ordinances”.

2) For Rectification of Errors Order, a version will be created for the section even there is only a typo error.

3) Although national laws do not form part of the basic law, they should be put on BLIS as a separate package.

4) The chapter number of the repealed ordinance will not be re-used in order to maintain multiple versions clearly.

5) For those sections without a commencement date or with a later effective date, a remark “not yet in operation” would be placed in the Remark field. It will be removed when the section comes into operation. This only applies in the case of now whole enactments not yet in operation, not amendments.

6) A pencil mark is added to the section pending for amendment on the day when the amendments commence. It should be placed in the current version only and will be removed after the amendment is made.

7) A new version should be created for all sections if the title of the ordinance or subsidiary legislation is amended.

8) One version can include numerous amendments but with only one version date except in the case that some amendments commence at different time within the day.

9) If the commencement date of an ordinance relies on that of another one, both gazette references of the commencement for the ordinances should be placed in the Gazette Number field in the Profile Bar.

10) To create a new version for the Long title or Empowering sections, if there are textual amendments to its contents it is not necessary to create a new version for changes to the commencement history.

11) If a whole ordinance or subsidiary legislation comes into operation in one single day, we should put a version date to the Long title or Empowering section. Otherwise, if it commences section by section without explicitly mentioning the commencement of the Long title or Empowering section, the Version Date field of these sections should be left blank.

12) For constitutional instruments not given a chapter number in the Loose-leaf Edition of the Laws of Hong Kong, an unofficial “chapter” number is assigned to it in the BLIS for identification purposes.

13) If an ordinance or subsidiary legislation commences and is repealed on the same day, two versions will be created, one is the old version showing the full text and the other is the current one showing the repeal. For example, see chapter 541G.

14) If a whole ordinance or subsidiary legislation is repealed, a new version need not be created for those sections already repealed or omitted.

1) Mark all gazette amendments to a register (DMA document) every Friday.

2) Looseleaf team will prepare manuscripts and send to BLIS team with the target time of within one week after publication.

3) BLIS team edits the database according to the manuscripts from the looseleaf team. If the looseleaf team cannot meet the schedule, BLIS team will edit first according to the gazette and then check proof against the subsequent manuscripts.

4) Editors will proofread their work and then pass to law clerk for checking.

5) BLIS team informs looseleaf team if there is anything wrong in the manuscripts.

6) BLIS data should be the same as in looseleaf edition.

7) There are differences between BLIS and looseleaf: eg the format, multiversion and footnotes that the BLIS team usually put it immediately at the end of a section while looseleaf will put a note at the end of a chapter.

1) Add pencil marks to sections pending for amendments. To mark a section, click on that section once in the View Pane, then press the “Mark Change Pending” button. A little pencil will appear to indicate that section is being updated.

2) To amend a section:

(a) Create versions:

i. Enter into the section , click “Create draft” button,

ii. Incorporate all the amendments and click “Publish New Version”. “Publish New Version” is a function to publish the draft copy to database as a new version and the old copy is kept as old version. The new and old versions are distinguished by the version date.

(b) Without creating a version:

i. Double click a section to enter into the editing mode.

ii. Do editing work and save it.

3) To add a new section/new ordinance: Click “New Document”. A blank form will be displayed. Then fill in the form and key in/paste text (a soft copy will be provided by printer).

1. On the day of Gazette publications, add pencil marks to all affected sections that have been amended but have not yet been updated.

2. Edit both English and Chinese databases.

3. Edit those amendments that have become effective.

4. We will not deal with the amendments that have not yet commenced.

5. New ordinances and new subsidiary legislation that commence in a later day or without a commencement date yet will be done if we have finished (3). A remark “Not yet in operation” will be added to every section to draw users’ attention. The remark will be removed on the day when it comes into operation.

We have six clerical staff, one law clerk and one senior law clerk II. All clerical staff are responsible for updating data to both Chinese and English databases. Law clerks are responsible for data checking and all system administration work.

[*] Manager, Information Technology and Resources, Department of Justice, Hong Kong

[1] <http://www.justice.gov.hk>

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/UTSLawRw/2002/5.html